Читать книгу The Compass Rose - Gail Dayton, Gail Dayton - Страница 13

CHAPTER FIVE

ОглавлениеKallista recoiled, hands flying up to push the madwoman away. She called for Torchay as she scrabbled backward across the stone floor, her voice a hoarse croak, surprised she still had a voice. She reached up to stanch the wound…but there was no blood pouring down over her undertunic. No pain. Carefully, Kallista felt her neck. There was no wound.

“So. You’re the new one.” The woman stood, tossed the knife on the table above. “How long has it been?”

Kallista ran her hands over the whole of her throat. How could that knife not have cut her? She had felt its sharpness, felt it prick her. “How long has it been since what?”

“Since I died, of course. What’s your name?” The woman poured wine from a silver pitcher into an ornate cup. “I’d offer you some, but I’m afraid you couldn’t drink it.”

“Why not?” Kallista got awkwardly to her feet, staring at the high chamber around her. It was dark, the windows mere slits in the gray stone walls, the candles blazing from bronze candlesticks insufficient to make up for the lack of sunlight. Banners in subtle colors with strangely familiar devices attempted to soften the stone, and a fire burned on a circular hearth, the smoke finding its own way out the hole in the roof. This was the most realistic dream she’d ever had.

“I can drink in my dream if I want to,” she said, recalling what the other had said about the wine.

“It’s not a dream.” The woman gave her a sour look. “Not exactly. You should know that—Here, what is your name?”

“Kallista. What’s yours?”

The woman laughed and took a drink from her cup. As she drank, the smile faded from her eyes. She set the cup on the table, staring at Kallista in shock. “You really don’t know me, do you?”

“Should I?”

“Yes.” The woman had no small opinion of herself if she expected a complete stranger to recognize her and know her name.

“Sorry.” Kallista lifted her shoulders in a tiny shrug. “I don’t.”

“How long has it been since my death? Since the death of Belandra of Arikon?”

Kallista stared. She was more than ready for this dream to end. It was becoming far too strange. “Belandra of Arikon never lived. She’s a story. A tale told by the fireside to frighten children and thrill young men.”

“I never lived? Never lived?” The woman—Belandra of her dreams—snatched up the silver cup and threw it across the room. Wine flew in all directions, none of it spotting Kallista’s pale blue undertunic.

“How then did I unite the four prinsipalities into one people?” Belandra demanded. “How did I fight and defeat the enemies of the One? How did I—” Her mouth continued to move, but Kallista could not hear her. It was as if some barrier had dropped between them, cutting off all sound.

In the far distance, she could hear Torchay calling her name and turned to go, to answer him.

“Wait.” Belandra caught her arm. “How long?”

Kallista felt Torchay’s voice pulling at her, drawing her back, but Belandra’s hand anchored her in place. “A thousand years. The four prinsipalities were united a thousand years ago. There are twenty-seven prinsipalities in Adara now. But the first Reinine was Sanda, not Belandra.”

The older woman’s smile showed a deep affection that made Kallista shiver. “My ilias was much better suited to governing than a hot-tempered naitan like me.”

Torchay called again, stretching her thin.

“I have to go.” Kallista clawed at the fingers holding her.

“Take this.” Belandra pulled a ring from her forefinger and pressed it into Kallista’s hand. “I will have many questions when next we meet.”

Which will be never, if I have aught to say about it. Kallista closed her hand reflexively around the ring. As soon as she did, Belandra released her. She went flying back through the light and the dark and the colors to slam into her body with a force that bowed her into a high arc. She gasped, drawing air into lungs that seemed to have forgotten how.

“Kallista.” Torchay held her face between his hands, fear in every line of his moonlit expression.

“I am here. I’m awake.” She resisted the urge to touch him in return, to be sure he was solid and real.

With a shaking hand, he brushed her hair back from her face, then sat up straight on the edge of her bed, setting his hands in his lap. “You were no’ breathin’,” he said, never taking his eyes from her. His thick accent showed the depth of his agitation. “You shouted, like you did before. I came to wake you, but you would no’ wake. Then you quieted. I thought the dream was over so I went back to bed. But you called my name.”

He stared at her, his eyes haunted. “You called my name, and you stopped breathin’. And no matter what I did, you would no’ start again.”

Kallista shuddered. Had that been while she was in that strange place talking to the woman who claimed to be Belandra of Arikon? Could some part of her have literally been in another place? That place? Impossible.

“I’m breathing now,” she said.

“Aye.” He was shaking, trying to hide it, but failing.

She reached for his hand. He took it, gripped it tight. But it wasn’t enough. She used his hand to pull herself up. She put her arms around him and held on tight until her trembling and his went away.

“Do no’ do that again,” he said over and over. “Ever. Do not.”

“No,” she said again and again. “No. I won’t. Never.”

When she could let him go, Torchay picked her up and stood her beside the bed.

“What are you doing?” She had to catch his arm to keep from staggering.

“Moving your bed. I’m too far away across the room. You’ll be sleeping next to me till the dreams stop.” He lifted the bedding, mattress and all, from its rope frame and set it on the floor. “We can bring in a larger bed in the morning.”

“It’s against regulations—” Kallista began, but fell silent at the flash of his eyes.

“It’s against regulations for me to allow you to die. It’s against nature for you to stop breathing like that. I want you at my back.” He crossed the room to collect his mattress from the doorway and laid it beside hers. He was on his knees rearranging the blankets when he paused.

“What’s this?” Torchay plucked a small object from the tangle of her blankets.

“I don’t know.” Kallista held her hand out for it. “What?”

“It’s a ring.”

She could see it now as he held it up to the candlelight, examining it. Cold coursed through her veins.

“I didn’t know you had a ring like this. Pretty.” He set it in her hand and went back to straightening blankets.

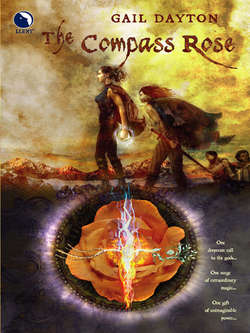

Kallista didn’t have a ring like this. It was thick and gold, bearing the marks of the hammers that had shaped it. Incised deeply into the flat crest was a rose, symbol of the One. The ring was primitive and powerful. It called to her, demanding that she put it on. Kallista curled her hand into a fist, resisting the urge. She did not own this ring. She could not. Because it had been given to her in a dream.

She opened her hand and let the ring fall to the floor. She didn’t want it, didn’t want what it might mean.

“Careful. You’ve dropped it.” Torchay shifted to his other knee and picked it up. He held it out to her but Kallista ignored it, so he set it on the chest. “You’re too tired for words. Not breathing’ll do that to you. Come to sleep.”

She was tired. Tired of strangeness and impossibilities and mysteries she couldn’t comprehend. She wanted her life back the way it had been before the Tibran invasion, but she feared that was one of the impossible things, and it frightened her.

Torchay lay down and turned his back to her, waiting for her to set hers against it. Careful in her weariness, Kallista stretched out on her own pallet. Rather than turning her back, she tucked herself in behind him and wrapped her arm around his waist. He startled, then lay still. Too still, as if afraid to move, to breathe.

“I need to hold on to something tonight,” Kallista said. “Let me hold you.”

He didn’t reply, but the tension slid out of him. She snuggled closer, the tip of her nose just touching the top of his spine. This was against regulations, rules she had carefully kept for years. The rules had a purpose, one she agreed with. But right now, tonight, she didn’t care. She needed to hold on to something that was real, that was flesh, blood, bone, against the dreams coming again.

Aisse lay in her hiding place for a day, a night and another day. She crawled out only for water. By the second night, though every inch of her body ached, she could stand, and even walk without too much dizziness.

The noise of the camp—animals bellowing, men shouting, warriors marching—sounded much too near. Now that she could walk, she needed to move farther away, to a hiding place where they couldn’t find her no matter how hard they searched.

She crawled back beneath the tree and gathered her few pitiful belongings, then she returned to the riverbank. Aisse looked downstream, toward the camp. That way lay death. She turned her face upstream and began to walk. This direction might not hold life, but as sure as the sun rose every morning, she knew it at least held hope.

Three days later, Kallista had finished all ten of her damned notification letters and delivered them to headquarters, to be included with the next set of dispatches to the capital. River traffic had returned almost to normal. The Tibrans no longer had enough manpower to interdict travel by boat along the Taolind, and they’d never had enough boat power. The river was the best means of travel to the interior, to Arikon far to the west, and regular dispatches were getting through again.

But now, Kallista had nothing to do. She had no younger naitani to train in their magic. She had no call on her own magic once she chased the cannon from closing on the river gate. Her paperwork, the bane of her existence, was complete. She’d even had time to experiment on her hair with Torchay, settling on simply tying back her front hair in a small horsetail on the back of her head, and leaving that behind her ears to fall free over her neck. She was bored.

Boredom and curiosity had her taking the long way from her billet to the Mother Temple’s library by way of the breach in the western wall. Repairs had begun already and Kallista wanted to see how they were going.

Torchay stalked at her side like some bright avenger, scowling at anyone who came close. He didn’t like all the gossip about the “scythe of death” as the dark magic she’d done was beginning to be called. He took the epithet personally, unable to shrug it off as well as Kallista could, which wasn’t all that well. She tried to tell him it was useless to resent people for their ignorance, but he didn’t seem to hear.

The streets grew thicker with people as they neared the breach. Kallista could see the two walls of mortared stone that formed the inner and outer surfaces of the city wall, and some of the rubble filling the wide gap between the two walls that provided much of its strength. Civilians and a few companies of infantry conscripts swarmed the breach now, clearing away the broken and fallen stones so the walls could be repaired.

She frowned, squinting against the sun’s fierce brightness. The scene seemed familiar, as if she had been here before. A woman dressed in darkest blue straightened, beckoned to the child carrying the water bucket. And there—two men used iron bars as levers to pry up a larger stone. And the brown-haired woman in red lifted the shoulder yoke holding two filled baskets and staggered toward the dump. Kallista clutched Torchay’s arm as terror froze her in place.

“What’s wrong?” Torchay looked outward, hunting the threat.

She couldn’t answer. This was her dream. She had dreamed it four nights in a row, always the same. Now, the man in the white tunic would call his daughter down from the pile of rock. He did. Her eyes snapped to the southern edge of the broken wall. The thin trickle of sand poured from the mortared interior.

“Get back!” she shouted, throwing herself forward. “Get away from the wall! It’s going to fall!”

Unlike her dream, heads turned. People heard her. They started to move, slowly at first, uncertainly. But when the trickle of sand became a stream of gravel, they ran.

“Hurry!” Kallista snatched up the disobedient girl and thrust her into her father’s hands. “Run! That way!”

Torchay grabbed Kallista and shoved her into the shelter of a deep doorway just as the first of the dressed stone fell from the top of the mortared wall to shatter on the street’s cobbles. He held her there, shielding her with his body until the thunder of falling rock ended and he allowed her to push him away.

Fine dust clouded the air. Kallista coughed as she peered into the collapse, trying to see broken limbs, crushed bodies.

“This was your dream.” Torchay’s voice held no doubt.

“Yes.” There should be casualties. A child’s body there, beneath that largest stone—but no, Kallista had given that child to her father. And the woman who should be moaning, trapped over there with her face bloodied—Kallista had seen her run into an alley two houses over.

As the air cleared, people began to emerge from the cover they had taken, staring about them from frightened eyes in dust-whitened faces.

“Who’s hurt?” Kallista shouted. “Is anyone missing?”

“My sedil, Vann,” a man called.

“No,” another answered. “I’m here. Not hurt.”

The workers milled about, shouting an occasional name, but in the end, all were accounted for. The cuts on Torchay’s legs and back where the shattered rock had struck him were the worst injuries. He and Kallista had been closest to the collapse.

“But how did you know?” the mason in charge of repairs asked. “How did you know it would fall? Even I had no warning.”

Anxious to get Torchay to the temple for healing, Kallista did not want to take time to answer. Torchay hung back. “Do you not see the blue of her tunic? She is a North naitan. She can read the earth and the things carved from it. Not often. But sometimes. When there is danger.”

“Ah.” The mason nodded in understanding as Kallista urged Torchay on.

“Your back is still bleeding badly,” she scolded. “We do not have time for these delays.”

“Better to give them an explanation they can swallow than leave them to wonder and invent something even more outlandish than the truth.”

“Fine, fine. It’s done.” Kallista lifted her hand from the deepest cut to find it still bleeding. She put it back, but it wasn’t easy to maintain sufficient pressure as they walked. “Just don’t bleed to death before we reach the temple.”

Torchay chuckled. “Such tender concern for your underling.”

She pressed harder, knowing it hurt him, but wanting the bleeding to stop. “Hush.”

For a while he did, but she knew it was too good to last. “While they’re tending my back,” he said, “I want you to talk to Mother Edyne. Tell her about the dreams. Tell her everything.”

Kallista scowled. She didn’t want to. If anyone else knew, it would somehow become more real. “I’ll consider it.”

“Tell her, Kallista. You must. It’s no’ normal, what’s happenin’ to you. What if you stop breathin’ again and I can’t bring you back? I didn’t last time.”

“Yes, you did.” They hadn’t talked about what happened, though they’d slept back-to-back every night since then. She didn’t want to talk about it now, but it appeared Torchay was of a different mind. “You called me back.”

“Back from where?” He stopped at the temple door and gripped her arms, the light, clear blue of his eyes blazing almost white as he glared at her. “Where were you? It wasn’t a dream, was it? You don’t know what’s happening to you. I certainly don’t. You need to find someone who does.”

“You think that’s Mother Edyne?”

“I don’t know. Neither will you until you tell her.” His hands tightened, digging in till it almost hurt. “Promise me you’ll do it.”

She dragged her gaze away, stubbornly silent. She couldn’t make that promise. She just couldn’t.

“Pah!” Torchay pushed away and strode into the temple.

Kallista scrambled to catch up, rushing down the long corridor after him. “Dammit, Torchay, you’re bleeding again.”

“Let it.” He rounded on her again, just outside the entrance to the sanctuary, bending down until his nose almost brushed hers. “At least I have sense enough to be going to get it mended, unlike some too-stubborn-for-her-own-damn-good naitan I know.” He whirled and stalked across the worship hall.

“Torchay—” Kallista called after him, but he only gave one of his disgusted growls. Better to let him go. Maybe he’d be in a better temper later.

She wandered toward the center of the worship hall, her hand drifting to the ring in her pocket, the one she could not possibly possess. The ring given to her in a dream. She had yet to put it on a finger, but neither had she been able to leave it behind, lying on the chest in her room. She’d carried it in a pocket the last three days.

Kallista drew the ring from her pocket. The rose on its crest was identical to the one inlaid in the center of the temple floor, the faint reddish hue derived from the wax left behind when it had been used as a seal. What did it mean? How had she come to possess it? She had far too many questions and far too few answers.

Perhaps she should consult Mother Edyne. But what could an East magic prelate of a provincial temple know about mysteries such as these? Kallista started to put the ring back in her pocket and almost dropped it.

She caught it again, gripped it tight in her hand, heart pounding. She couldn’t lose the ring, no matter how little she wanted it. Somehow, she was certain that it was a key to many of the answers she wanted. She didn’t understand how an inanimate object could answer questions, but the certainty would not leave her. Perhaps she was meant to look the ring up in some archive or other. However the answers were to be had, she could not lose the thing. And the safest place for it…

Kallista sighed, resigned to the inevitable. She removed her right glove and slid the ring onto her forefinger where the dream Belandra had worn it. But it would not fit over her knuckle. Her hands were apparently bigger than the dream woman’s. The ring went on the third finger of her right hand. It looked good there.

“It’s about time.” The woman’s voice behind her brought Kallista spinning around so fast, she lost her balance. It could not be.

But it was. Belandra lounged carelessly against the wall not far from the western corridor. She looked younger than she had in Kallista’s dream, her hair a brighter red, her body more slender, but still a decade older than Kallista.

“Who are you?” Kallista wavered between backing away in horror and drawing near with curiosity. “How did you come to this place?”

“I told you. I am Belandra of Arikon. As for how I came here—you brought me.” She gave a mocking smile as she waved her hands in a flourish. “You have questions? I have the answers. Unfortunately, I am not allowed to give you all of them.”

“Why not?”

“Because some things you must learn for yourself.”

Kallista shook her head, trying to clear it. That wasn’t what she wanted to know. She tried to sort the questions crowding her mind, to find those most urgently needing answers. “How did I get this? What is it?”

“A ring.” Belandra rolled her eyes, seeming to mock Kallista for asking something with such an obvious answer. “And I gave it to you back before I died.”

“A thousand years ago.” Kallista let her doubt show.

“Give or take a few dozen, about that.”

“That’s not possible.”

“For the One, all things are possible. Obviously it did happen, because I am here talking to you. You had to have something of mine in your possession before I could come to you. And here I am, at your service.” Belandra pushed herself off the wall and bowed, as much a mockery as most things she’d done.

“You’re a ghost.” Kallista didn’t believe in ghosts. Or thousand-year-old dream rings. But the one on her finger had come from somewhere.

“Something like that, but not exactly.” Belandra shrugged. “Oresta who came before me explained it, but I never quite understood. Does it really matter? I’m here now. And I probably ought to tell you before you use them all up that you’re only allowed six questions each time I am allowed to come to you.”

“Allo—” Kallista cut herself off, trying to count up how many questions she’d already asked. She couldn’t remember. “Who allows it? When will you come back? What questions may you answer? What are the rules? Are you truly dead?”

Belandra waggled an admonishing finger. “That’s five. You only had two left. Which means I can answer the first two, but the others will have to wait until next time, provided you still want to ask them again. Though I already answered the fifth, if you will consider. Unless you believe I could still live after a thousand years.”

“I’m not sure I believe you ever lived at all.”

“Believe what you like. Your belief doesn’t alter the truth. Do you want me to answer your questions?”

“Please.” Kallista gestured for her to continue.

“It is, of course, the One who allows me to appear here before you, and at least one Hopeday must past before you next summon me.”

“I didn’t summon you this time.”

“Did you not? You put on the ring. You desired answers. I am here.” She gave Kallista a sardonic grin. “My first year, I summoned Oresta every chance I got.”

“Your first year of what?” Kallista demanded. Belandra’s answers only created more questions.

“Apologies, my lady Kallista.” The grin on the woman’s face didn’t look very apologetic. “But you are out of questions.”

“Who are you talking to?” Torchay’s voice brought Kallista’s head around to see him walking across the worship hall as if he thought his steps might fracture the tiles beneath his feet. His expression held barely disguised fear. Behind him came Mother Edyne, whose expression was more guarded.

“To her. Belandra.” Kallista waved a hand in the other woman’s direction.

“Naitan,” he said, voice as careful as she had ever heard it. “There is no one there.”

Kallista turned, looked, and Torchay was right. “She must have gone.”

Torchay reached her, moved between her and the place where Belandra had been. “I have been here listening and watching for some time. Since you asked whether—she?…were dead. You spoke. You listened. You spoke again. And I saw no one. Who was it?”

She let out a long breath, looking past Torchay’s worried face to Mother Edyne’s curious one. “The woman who gave me this.” She held up her ungloved right hand, showing the ring. Mother Edyne, to her credit, did not flinch at the sight of the naked hand. “Belandra of Arikon.”