Читать книгу I Found Him Dead! - Gale Gallegher - Страница 5

2.

ОглавлениеI BROKE a date for dinner that evening. I had too much on my mind for company. I dined alone at a place on Central Park South, near my apartment. Louis, my favorite waiter, assured me everything was to my liking, and I took his word for it. For once I wasn’t paying attention to food. I was too busy considering the facts I’d gathered on Eddie Wells.

After Dawn left, Patsy and I set to work to earn those two lovely green bills. Digging up information fast isn’t easy, but I know a couple of places specializing in information on theatrical people. I shot Patsy over to those agencies.

By midafternoon she had an envelope of faded press clippings and cracked publicity pictures, covering the vaudeville days of Eddie Wells. There were also pictures of his partner, Ethel Wells, in buckety hats and knee-high dresses that would have set the present Dawn Ferris’s teeth on edge.

Our own master files turned up more recent leads. There were several inquiries on Eddie Wells, variously known as Ed Welsh and Ned Wills. These were warning sheets from Western agencies who were looking for him. We wired for details.

I didn’t expect much from these inquiries. They were after him for bad debts. For my money, it’s a waste of time to trace men like Eddie for debts. They’re dead beats and strictly uncollectible. But they’re easy people to trail.

I checked with the Bureau of Vital Statistics. There was no record of a child born to Edward and Ethel Wells on May 5, 1933. But there was a birth certificate recorded on that day for Elizabeth Anne, daughter of Theodore and Sylvia Alexander. I asked for a photostat.

I reread news stories on the kidnaping. On Friday afternoon Bette Alexander had stepped from the station wagon of the exclusive Purvence School, waved to her friends, and run through the gates of the family’s palatial home near Huntington, Long Island. She was not seen again. A thin, rather plain child, she was tall for her fourteen years, an excellent swimmer, and a fine horsewoman. An accident was suspected until the ransom note was received on Saturday night. Then the FBI joined the Suffolk County police in the hunt.

There were interviews with Bette’s mother, Sylvia Alexander, a handsome blonde of about forty, and with M. E. Baxter, the Alexander family lawyer and an executor of the estate. Also with John Bartley Crane, society artist, specializing in portraits of children, whose recent painting of Bette had been so widely used.

I called up a few people I knew. One of Dad’s old pals, a former Suffolk County detective, now working on the Alexander case, also a News reporter who had a by-line story on it. I kept my questions very casual, but from what I gathered in talking to them, there wasn’t the slightest indication that Bette was the adopted daughter of Sylvia and Theodore Alexander. Besides, there was also that matter of the estate I’d mentioned to Dawn. Would a man leave his entire fortune to an adopted child without some mention of that legal angle?

Very thoughtfully I left the restaurant and walked out into the soft March evening. Spring was early, but early or late, it irritated me. Spring always does. It seems to affect a weak and defenseless appeal, like a fragile female in white. I like autumn. Autumn is mature and strong and able to take care of itself.

But spring was with me that night, fuzzing everything into gentle curves, giving the bare trees a slightly pregnant look. There was a fragrance from the park that defied the aggressive fumes of carbon monoxide and incineration. There was rain in the air, and the low clouds were luminous from the lights of midtown Manhattan. I belted my all-weather coat, pulled the brim of my felt hat forward, and set out toward Central Park West. I like to walk in the rain. And besides, I wanted to look at a house in the West Sixties.

The address was in that narrow wedge of streets formed by Broadway and the west boundary of the Park. There was a large apartment house at the corner where I turned left toward Broadway. Behind the elegant frontage facing the Park, the street seemed to crumble. In the shadow of fine buildings and lofty towers, old brownstone houses huddled in shabby embarrassment.

Here spring was defeated. Moldy cellars, stale beer, and furnished-room cookery won out. The street lights were far-spaced and dim. The lights from the houses added only furtive bleakness. I walked faster, stumbled against a refuse can midway from the curb. A radio somewhere blared with studio laughter. A child cried. A couple walked past me, arguing—a young couple full of bitterness. Ethel and Eddie might have been like that.

Two doors from the next corner I spotted the house, primly respectable among its slatternly neighbors. The doorknob shone. The long front windows gleamed against chastely drawn drapes. There was no light visible. A tiny name plate in metal gleamed against the stone. Dr. Wurber. No initials, no Christian name, just the identification. Dr. Wurber.

I mounted the high stone steps and pressed the bell. I heard it jangle through the house. I pressed a second time, more persistent than hopeful. The echo had an empty sound.

“Well, now, and what do you want?”

The sudden gruff voice so startled me I almost went over backward. He was standing in the small areaway at the side of the steps where a door led into the basement. Though he was half lost in the shadows, I could make out dimly the scowling face of a thickset, white-haired man in shirt sleeves and suspenders.

“Who is it you’re after?” he asked, with a stubborn hostility.

I came down the steps quickly. I smiled and said gently, “You startled me. Didn’t know where the voice came from. I wanted to see Dr. Wurber.”

“Not in. Won’t be in.”

“You’re sure?” I leaned against the iron rail surrounding the areaway. The old man, only a few feet from me now, stared nearsightedly.

“Did you—have an appointment, ma’am?” His tone softened.

“I thought I did,” I said breathlessly. “I came so far . . .”

The myopic eyes peered with embarrassing directness in the general area of my waist. I was thankful for the bunchy coat.

“Did you have an appointment for this night?” he persisted.

“It’s—April twenty-fifth, isn’t it?”

“It is that,” he said, edging out of the enclosure as he fumbled in his pants pocket. “Doctor’s a great hand for comin’ unbeknownst to me. Sometimes meetin’ his patients right here on the step. Would you be early now?”

“I might. Is it eight-thirty?”

“ ’Tisn’t that yet,” he said in obvious relief, and went before me up the steps. “I shouldn’t be lettin’ you in, but the night’s damp an’ in your condition . . .”

He unlocked the front door, switched on the lights, and led me into the big living room. I took a bill from the wallet in my pocket, pressed it into the gnarled hand.

“You’ve been so kind,” I murmured.

He beamed under thatched brows. “Nothin’ at all, ma’am. My wife went through it eleven times an’ I always say if you stay out of the night air . . .”

I sat in a large leather chair near the double doors, and picked up a magazine as the old fellow left. I didn’t move until I heard him go down the outer steps and close the basement door.

Luck, I decided, was riding with me. I couldn’t be sure there were any fourteen-year-old files here, but it was too good a possibility to pass. The answer to the whole thing—whether or not Dawn Ferris’s child and Bette Alexander were the same person—might be tucked away in some neat corner in this office.

I waited until everything was quiet. No sound at all if you counted out the pounding of my own heart. But the janitor might be somewhere below, listening. I kicked off my pumps, moved cautiously, in stockinged feet. The carpet pricked through my nylons as I crossed the room. A gloomy room, long, narrow, and high-ceilinged; the windows, only at the front, were shrouded in long, beige draperies. There was a scattering of heavy dark furniture and an aura reminiscent of the convent infirmary, a mixture of closed rooms and medications.

I reached the dark oak doors with the frosted glass paneling that formed the office partition. Except for my shoes, I was still dressed for the street, including gloves. I took a firm grip on the knob and turned gently. The door opened.

The light from the one lamp behind me revealed only shadow on the waxed linoleum floor. I reached out for the wall switch, found a panel with several buttons, pressed one.

Instantly I was bathed in glaring white light, sudden as a scream. I shut it off quickly, but the picture of the room was fixed in my mind, like a scene viewed by lightning. I could have diagramed the desk, chairs, files, and bookcases, the two long windows at the rear with shades drawn level with the sills. There was no evidence of surgical equipment. This must be an office and consulting room.

In the far corner beyond the desk was a group of filing cabinets, on which stood a gooseneck lamp. Not trusting the light buttons, I followed the line of the wall, my cold feet in sweat-damp stockings sliding on the waxed floor. The light from the living room guided me past major hazards. Carefully I reached the lamp, tipped the shade low, and turned the switch. For once I was happy to see the dim yellow gleam of a twenty-five-watt bulb.

Before me were two tiers of green metal filing cabinets. I pulled gently at the top drawer. The doctor evidently wasn’t worried about intruders. The drawer slid open easily. It was filled with eight-by-five folder-type cards, designed for the history of the patient and his correspondence.

Only there was no correspondence. The folder sections were empty. The cards, however, were all filled out in the same neat square handwriting. It was the second bit of unusual penmanship I’d seen that day. But this was the extreme opposite of Eddie Wells’s florid, show-card hand. This script recalled the writing on library cards when I was a kid. Every card in every drawer was written in that same style. Hundreds of them, and every entry made by the same person.

I squatted on my heels to reach the W’s in the bottom drawer and flipped through the carefully filed cards. Dr. Wurber had a passion for organization. He could give Patsy lessons in filing. Welch—Weller—Wells . . .

My hand shook as I drew out the large card. The writing danced before my eyes. I held the card closer to the dim light. Wells, Norma . . . I could almost taste my disappointment. Quickly I went back to the file. The next card was Wellward. I put it back slowly.

Were these really case histories? If so, how far back did they date? I pulled out the record of Norma Wells again. It was dated January 1942, but there was no street address or telephone number on the lines provided for that information. The many other entries looked like algebra problems, with letters and numbers together. Obviously the thing was in code.

I looked at several others. All the same. Names only and one date. All other entries coded. I ran through other cards in the W’s, noting dates. They went back to 1928. If Ethel Wells had ever been here, there should be a card.

Putting the file in order, I closed the drawer. These might be records of foster mothers. If Dr. Wurber delivered Ethel Wells’s child, he would have placed her for adoption. And if that child was now known as Bette Alexander . . . I started to rise but my legs were stiff from the cramped position. I stretched up slowly. Slowly, too, I was aware of a change.

The house was no longer still. Not that there was any definite noise. Simply that the place was no longer empty. Without turning, I realized there was someone close. Someone behind me, in the doorway. It could be the Irish janitor, but I knew it wasn’t. I continued upward by slow motion to a standing position. My own breathing seemed to stop.

“I would stay right there, if I were you.”

The voice was querulous but authoritative, as if the words were reinforced with steel—or lead. I stood rigid, staring at the gracefully curving gooseneck lamp.

“I am surprised,” the voice went on, in an injured tone, “that he would resort to such methods. Does he think I’m a fool?”

There was obviously no answer to that, so early in our acquaintance. But who did he think I was?

“Face me!”

I moved very slowly, trying to frame a good out. It was only seconds. Then I confronted a short, plump, middle-aged man. He was totally bald and his round face hairless except for thick sandy eyebrows, unexpected as parsley on a custard. His tan gabardine suit was smartly tailored, his linen custom made, his surprisingly small narrow shoes gleaming. In his small fat hand he held a small square gun. In that peculiar way my mind works, the hand reminded me of the writing on those cards.

If my initial survey was thorough, it was also quick. He, in turn, looked me over with irritating deliberation from my Knox hat to my shoeless feet.

“You are lovely,” he said finally. “He told me you were but I didn’t believe it. I expected something younger and cheaper. The floozy type. What does he have to offer a girl like you?” He was moving around me. “Take off your hat.”

I took it off. He moved closer, teetering like an unsure ballet dancer. I had an unpleasant feeling that he was going to touch my hair. I didn’t like those lard-white hands. I didn’t like him. If only I could find out who I was supposed to be . . .

“A brunette on the auburn side. I thought you were more of a redhead,” he said. “Intelligent, too. Much too intelligent to get involved with a down-at-heel punk like Eddie Wells.”

I gave an involuntary start. Noting it, his lips parted in an unpleasant variation of a smile.

“You see I did know you, Cora. Eddie told me about you when I went to see him in that hole—last Thursday.” He made a disgusted sound in his throat. “He didn’t mention that he would send you to search my office.”

For a moment I felt dizzy. Eddie Wells . . . Cora . . . Eddie’s girl friend, obviously. They somehow were linked with this man, and as recently as last Thursday, the day before the kidnaping. I was on the track of what I was seeking, but where it might eventually lead I didn’t know.

“Since we recognize each other, Dr. Wurber,” I said, “you can put the gun down. I am not armed.”

He studied me from under those eyebrows, decided to accept my statement, dropped the gun into his outer coat pocket, waved his hand to the chair beside his desk.

“Sit down, Cora.”

I obeyed almost gratefully. He pressed the proper button on the panel and soft wall lights went on. Then very deliberately he sat in his big chair, just around the edge of the desk from me. Silently he lined his pencil, pen, and paper cutter on the blotter before him. I half expected him to produce one of those big cards.

“You are a very foolish girl,” he said, in that thin whine. “I could have you arrested for gaining entry under false pretenses.”

That was a bluff. My confidence mounted faintly from zero. I made my eyes wide.

“I hope you wouldn’t do that, Dr. Wurber. Eddie would be mad.”

“I don’t see why you should mind what he thinks.” His eyes were still on their sight-seeing tour. I crossed my knees, deliberately, smiling apologetically as I glanced from him to my shoeless foot. His eyes beat mine by seconds. I drew my feet together demurely under the chair. The guy gave me the creeps.

“I don’t see why you should mind at all,” he repeated impatiently. “About him, I mean.”

“Perhaps I’m fond of him.”

Wurber made an unpleasant chortling sound. “What women see in him . . .”

“I suppose girls want to mother him,” I said softly.

“Well, I want no part of him. All my years in New York—not a word against me—and now this!”

“You mean last week—or tonight?”

His pale eyes peered from under those brows like clams in a cave. “Tonight?”

“That wasn’t like you thought—like it looked.”

“No?”

“I was curious, that’s all. I didn’t want that nice janitor to hear me, so I took off my shoes. I hope you won’t tell Eddie.”

“My dear young lady, I never expect to speak to him again on any subject. I thought I made that clear to him.”

“He said . . .”

“He said . . . he said . . .” Wurber parroted. “Whatever he said, I believe none of it.”

He pulled out a faintly scented handkerchief, mopped his brow. I glanced down at my gloved hands, folded in my lap, and figured my chances. Dad always said play your cards as though you held a royal flush. The next play in this game was a hazard.

“Eddie didn’t send me here,” I began, and the tremor in my voice was genuine. “I came because I thought you . . . were his friend.”

He gave an impatient grunt. I kept on, without looking at him, feeling the thin mounting tension I’d known as a little girl when I made up stories to tell Grandma. “Eddie’s hurt.”

“You mean—Eddie has taken offense—at me?” Wurber was getting cute.

“I mean—he’s injured. Shot.”

“Shot!” Wurber squeaked. “By whom? How?”

“It was an accident.” My nervousness was a helpful prop to the act. “He slammed the drawer, the gun was in there, went off. The bullet grazed him.”

Wurber obviously didn’t believe my account of the accident. “You should have called an ambulance if he’s badly hurt.”

“I would have, but to get an ambulance from a city hospital you have to call the police first. Even private hospitals—and most doctors—report an accident with firearms. Don’t they?”

The doctor ignored the question, asked another with icy annoyance. “And Eddie doesn’t want to see the police?”

“You know that.”

“Where is he?” Wurber demanded irritably.

“In . . . that hole, as you called it.”

“Curse the day I ever saw the man,” Wurber muttered. “He’s always brought trouble.”

“But you must come,” I persisted. “You couldn’t let him die. That would bring the police, too.”

I didn’t look at him. I kept my eyes lowered, for the demure effect, the helpless, spring expression. “You will come?”

“I am still a doctor,” he said crossly, “even though—at times—I think it would be better if some people were to die.”

A soft veil of rain enveloped the street when we came out. An impressive car with a New Jersey license was parked a few doors away. I was sure it belonged to Wurber, but he ignored it and headed toward Broadway. At the corner, in front of a dingy, eighth-rate hotel, we picked up a cab. I popped into it, my hand on the opposite door handle, just in case.

The cabby was looking at him. Wurber hesitated, glanced at me. My hand tightened on the door handle. My expression, I hoped, was perfectly blank. Wurber gave a number on Third Avenue, got in, and sat beside me, close. I released the door handle.

The driver looked around. “Is that in the Seventies?”

“Near Ninetieth Street,” I said automatically. I’d been dunning a man only a few numbers away.

Dr. Wurber nodded. His bushy eyebrows close together under the brim of his hat gave him a totally different appearance. With him, a hat was a disguise. He settled back, his knees spread, touching mine.

I sat in rigid silence, my mind ticking faster than the meter as we crossed 72nd Street and entered the Park. The silent rain misted the lights and the windshield, filled the air with fragrance. I tried to relax, get an easier hold on myself, but my nerves wouldn’t unbend.

What I needed was a good plan, and how could you plan when you didn’t know what came next? This could be a trap in reverse. Wurber might be leading me into one of his own. I had to take that chance.

The cab wound skillfully through the maze of drives, the tires singing on the wet road. The buildings along Central Park South gleamed like a fairy city through the rose-gray mist. I thought of the nice safe restaurant where I had dinner and of my apartment, around the corner from it. Surely nothing serious could happen this close to home. Dr. Wurber’s elbow brushed mine and I started.

“Cigarette?”

I took one, accepted his light, couldn’t avoid his fat little finger lingering against mine. My skin crawled. After all his dealings with women over the years, I wondered he ever wanted to see or touch another one; but he obviously did.

The cab crossed Fifth Avenue, headed east, then took Park Avenue, north. It was such a very little way now. I tried to empty my mind. This was no time for crossing bridges, coming or going. I had connected Dr. Wurber with Eddie Wells. If he took me to Eddie Wells, he might take me indirectly to Eddie Wells’s child.

The cab turned under the elevated into Third Avenue. I noted the number on the first store. The address Dr. Wurber gave was in the middle of the short block. It was a rag-tag section, with cheap flats and rooming houses over small stores, the entrances to the dwellings wedged between the shops.

We stopped. Wurber paid the driver and we crossed the wet sidewalk, Wurber clutching his black bag and picking his way in those small pointed shoes. I strode into the dingy entrance as though I knew where I was going. There were some battered mailboxes in the dirty wall of the vestibule, bells with indecipherable name plates. The door opened when a man walked out. I caught the door and Wurber and I walked in.

The hall smelled of bad plumbing, cooked cabbage, and everlasting darkness. I hung back, let Wurber go before me up the creaking, grease-slippery stairs. A girl of about fifteen ran past us down the stairs, her child mouth heavy with make-up, her cheap red sling pumps clattering. I shuddered. Certainly I’ve seen poverty, and drab little girls trying to be beautiful. But there was something about this place that was worse than poor, worse than dirty. It had an almost melodramatic air of evil, like a scene in a movie. A dingy, damp, friendless place.

Dr. Wurber, panting, turned at the third-floor landing. I followed him through the narrow hall, lighted by a single feeble bulb. He stopped before a door. So did I.

“Well, let us in,” he said impatiently. I put out my hand before I realized what he meant.

“I . . . I don’t have a key.” Still holding the knob, I knocked with my free hand. There was no answer. I knocked again. Dr. Wurber was fuming.

“Coming out . . . leaving this man . . . anybody could have walked in.”

I turned the knob. The door was unlocked. Cool air blew across my face as I pushed the door open. I realized a window was raised. I reached for the wall switch as a train roared by, shaking the building like an earthquake. In the passing glare, I glimpsed the line of the light cord in the middle of the room. I moved quickly and pulled on the light.

With my hand still on the greasy, fly-specked cord, I surveyed the dingy kitchen-sitting room. Empty beer bottles and crusts from sandwiches littered the deal table. A fact-detective magazine lay on a chair near the window.

Behind me Wurber was saying, “Where is he? What have . . .”

There was a door ajar, leading into another room. I said, “In there. That’s where he was.”

There are some things you know. Some things you know without ever realizing how the meaning came to you. But this was not one of those occasions. I had no premonition as Wurber pushed open the door. I was on his heels as he stopped, gasped, muttered oaths as he found the pull cord for the light. Then he stepped aside.

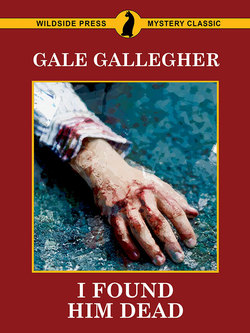

Lying on that rumpled, unmade bed, still in trousers and shirt, was Eddie Wells. No mistaking the face, the upturned nose, the winged brows, the petulant mouth. Nor was there any mistaking the hideous hole in his forehead, the dark smear of blood across the upper half of his face, the crimson splotches on his shirt.

Dr. Wurber was staring at me. Accusation—ghastly clear—burned in those pale eyes.

I’d said Eddie was shot. That was what I told Wurber—to bring him here. And I’d been right. That was the fantastic fact I had to face now.

Eddie had been shot. He was dead.