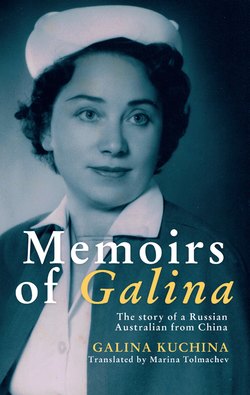

Читать книгу Memoirs of Galina - Galina Kuchina - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Early Life

ОглавлениеI was born in the Manchurian province of northeast China in the house of my grandmother, Varvara Mihailovna Antonov.

My father, Ignatii Kallinikovich Volegov, was an officer of the White Army, which fought against the Bolsheviks. After the overturn and disbanding of the Czar’s Army, my father managed to reach Siberia where he organised Cossack regiments to continue the fight against the Bolsheviks. He survived the ledanoi pohod (the Ice March) and found himself outside his native land with the departing, but heroic, White Army. This tragic retreat of the army, together with other peaceful citizens, was accompanied by exhaustion, cold and sickness

Many years later I would find out that my father had been married before and, during this retreat, lost his wife and two daughters to illness. I also found out that he came from a family of Old Believers.

Manchuria, the town, was small and clean with a large and beautiful train station. The station had a detailed map of the railway network painted on the top section of the wall in the main hall. To me, as a small girl, it appeared quite grand and rather fascinating.

Galina and parents

Another favourite landmark of mine was the beautiful St. Innokenty Cathedral. Within its grounds was a children’s orphanage, a home for the elderly, and accommodation for priests, the choir master, members of the church choir and for other people who had some connection with the church.

Bishop Jonah, who has recently been raised to sainthood, was buried in its grounds. The bishop maintained a good relationship with the Soviet Consulate and through this ensured that the children and old people were given coal for the winter months.

One family, who lived on the church grounds, had a son who had never walked before. After the unexpected death of Bishop Ionah, the boy dreamt that the bishop came to him saying, ‘Take my legs, I don’t need them anymore. Arise!’. Next morning, the boy walked. This dream was officially registered as a miracle.

I remember a very large and beautiful department store; Dun Chan. Was it really that big and beautiful? It seemed so to me at the time. The Nikitinsky compound had a gorgeous entrance with polished brass handrails in front of the enormous mirror windows. There was a photo studio in the corner part of the foyer and a hotel was located above the store on the second floor. The Vorobiev Gastronom left an indelible impression on me.

Galina with friend, Galia Vorobieva

The aroma of delicious delicacies always aroused the appetite - the hope of getting something tasty from Mama or Babushka always excited me. I remember our visits to the market. I loved to run to the meat stall owned by my uncles. I could have reached them more quickly by circumventing the market but it was much more fun to run through and see all the Chinese stallholders.

In Zarechka, there was a cemetery where my grandfather, Feodor Maximovich Antonov, was buried. I don’t know why this area was called Zarechka (za meaning ‘over’ and rechka meaning ‘river’) because there was never a river there, nor any evidence of a river. The leather factory, where my father worked, was also in Zarechka. After their wedding, my parents lived in a flat on the factory site, however, they spent most of their time at my grandmother’s.

In Manchuria, there was a city park where we often walked in the evenings. Music always played there - it was a place for assignations and promenade. I can’t be sure if the town of Manchuria was indeed as I describe it, but this is how it appeared to me through all the periods of my life. My parents left for Hailar when I was three years old but would return to Manchuria a few times a year and stay at my grandmother’s. My mother would sew, dress me up like a doll and send me there during Advent or Lent. I often travelled the route to my grandmother’s alone.

An acquaintance of ours, Tolia Popkov, worked as a conductor on the train. Mama left me in his care for the journey and my grandmother and Aunt Liza met me when I reached Manchuria. I loved visiting my grandmother and these trips always gave me much joy.

For the Feasts of Christmas or Easter, Mama, Papa, the Lupov family, my mother’s older sister Alexandra Feodorovna (Aunty Shura), her husband Alexander Vasilievich and their daughter Vera came to Manchuria. My grandmother was very proud to have her family congregate around her. She loved her sons-in-law and would buy them their favourite cigarettes and drinks. She catered for each individual taste. Papa smoked Dubler and Uncle Alexander smoked Antik. She bought Antipas vodka for one and Zhemchug for the other. This is how it was with everything.

Antonov family portrait, taken after immigrating from Russia to China

China was welcoming to the Russian refugees. The Chinese accepted a defeated, exhausted but heroic, White Army with its accompanying civil citizens. Being adaptable, hard working and good business people, the Chinese were ready to establish a common ground with the Russians. By the time the refugees arrived, there was an established infrastructure in place.

On the 16th of August 1897, the Russian Spiritual Mission was established with an official opening ceremony to mark the official start of work on the building of the Chinese Eastern Railway. In keeping with the agreement between the two countries, Russia provided security for future service personnel as well as churches, hospitals, schools and houses for railway workers.

Family home in Hailar, China

My father writes:

The day when we needed to cross the Chinese border was upon us. About six to seven kilometres before reaching the town of Manchuria, there was no more cannon fire. The rifles became quiet. Somewhere there may have been an occasional shot fired but the constant whistle of bullets stopped. Logically, this quietness should have brought with it some relief at the thought that one is still alive, but in fact the opposite happened. It is difficult to explain but there was feeling of wanting to cry or shout. We were not ready at this time to say, ‘Forgive me!’. It is difficult to explain what we felt at that time to someone who had not shared a similar experience. To leave one’s own land and go into a foreign land, into which we were not invited, was not easy. All the riches of Russia, all that was accumulated by our predecessors, was left to our conquerors. Will we ever see you Russia, in the way you were? We do not know. Each one of us, filled with heavy thoughts, tried to surreptitiously steal a glance into the eyes of the other to gauge his level of suffering.

Many years later, I had the opportunity of meeting the renowned Russian author, V.G. Rasputin in Moscow. He said that he liked my father’s book and that some parts had real artistic merit.

Galina and writer V.G. Rasputin

From what I remember, he especially liked my father’s description of the actual Ice March. It was a tribute to the poignant retelling of what occurred by a person who was not a professional writer from one who was established in his field.

I answered, ‘Am I actually hearing this from you of all people?’

My mother was brought to Manchuria as a young girl. Her family included her father, mother, three brothers and four sisters. They had lived in the Ural town of Miass.

My grandfather, Feodor Maximovish Antonov, was an entrepreneur businessman/merchant. He traded cattle and grain. He built roads between surrounding villages and towns and was well-off, rich even. He had a marvellous two-storey house in the town square. His plans to send all his children to university came to nothing, with only his eldest child managing to finish high school.

The bloody revolution turned the wheel of history for the whole country and for individuals. The family lost land, property and money through leaving Miass. Having reached the station of Lebiaz, they took a freight train to China. The family managed to reach Manchuria, in spite of suffering from typhus during their journey. After all their wealth, their horses, carriages, stock and property, they began life in China in absolute poverty.

I visited Miass during a trip to Russia with my husband in 2000. Everything that my mother, grandmother and godmother told me about life in Miass became for me so clear and understandable. I visited their house and walked along the streets which my mother and her family had walked many years prior. I totally immersed myself into their previous life. I imagined myself as my mother, playing with dolls in the attic of their large merchant mansion. I imagined how they would have pulled me on a sleigh to school in winter after a filling breakfast of buns and aladii (pancakes). I imagined how I would have gone into the forest to gather berries and mushrooms. I saw all this as on the palm of my hand.

This visit to Miass opened to me a new world, a world which I had heard so much about from my mother. This previously imaginary world became for me a bright reality. In Hailar and later in Australia, my mother kept all the traditions that she inherited from Miass, her homeland.

The family brought with them two fur coats to Manchuria. One was made of ferret fur and the other of fox. From the sale of these, my grandfather bought several carcasses of beef from an abattoir and dairy products from a peasant’s farm. While one of my mother’s brothers, Kolia, worked for the railways, her older sister, Shura, my mother and her younger sister, Marussia, sold the meat and milk products, not in a shop, but at a market stall. They did this through summer and winter.

The youngest sister, Liza, went to school. The oldest brother, Diodor, bought cattle for slaughter. Kostia, the youngest brother, who had a talent for languages, travelled to various regions and negotiated with the Mongol and Chinese traders. This is the kind of childhood that was the fate of my family and my dear mother, who in the freezing cold spent days on end standing by her stall, occasionally warming herself at a stall owned by a kind Chinese man. All nine family members lived in one room.

In time, the Antonovs opened a butcher shop. They moved into more comfortable lodgings and the children were able to resume their schooling. They acquired land on which animals could be kept – not just for slaughter but also for farm work. They bought camels and arranged transport. Life became happier. For a long time the dream of eventually returning to their homeland did not leave them but the thought of returning to the Soviet hell was not an option. They settled in Manchuria.

My father’s fate was tragic. Unfortunately, I do not know much about his early life. Being a child, and later a young woman, the stories told by my father found their way into my consciousness, whereas war and politics did not interest me - how very sad.

Now, I would have listened and absorbed all the details of his stories. I do, however, remember my father speaking of a forest. I assumed that his parents were foresters. In fact, he came from a very rich family. This was obvious as both he and his sister studied in St. Petersburg and for a peasant to be able to send his children to the capital, he needed to be rich.

In 2000, during my travels throughout Russia, I searched through government archives and found that he was indeed of peasant stock from Perm. He completed technical school and became an ensign in the army. As an officer he was listed as a member of the non-hereditary nobility. He had been wounded.

The Russian Revolution occurred in 1917 and by 1918 the army disbanded. In his writings, ‘Memoirs of the Ice March’, we find that having reached Siberia; he formed a brigade at the request of the peasantry and heroically fought the Bolsheviks. At the end of the conflict, having been defeated, he found himself in Manchuria, where he fully comprehended the tragedy of all that took place. Much loved Russia was lost forever. Here began the life of an immigrant, full of belittling and difficulties both moral and material.

As a military man now in China, without another profession or a penny to his name, Papa, like all the other migrants, was in a difficult situation. His first job in China was cleaning out pigsties. He then worked in a bakery and after that found himself in a leather factory where he learnt to prepare and colour leather. My parents met during this time. They gently fell in love. My wise grandmother, Varvara Michailovna Antonova, saw my father as a good, honest man and blessed their marriage. A year after they wed, I was born.

The leather factory belonged to the Kataev, Gorbunov and Shmelev families. The Kataevs and Gorbunovs also came from Miass. Mama and Papa lived on the other side of the river from my grandmother’s home, near the factory.

After working at the factory for three years and having mastered the trade, Papa, together with Fedor Potapovich Riabkov, opened a shop trading in leather goods. Their initial stock included three pairs of boots and several pairs of shoes. They opened this store in Hailar and gradually the business flourished. They expanded into making leather coats and eventually had a large store which sold many goods, all of which were made on the premises. This naturally necessitated a move from Manchuria to Hailar.

As a child, however, I did not like this first store. To me, it appeared narrow, dark and totally unimpressive. It did not have any toys – no dolls

As previously mentioned, Dun Chan met my taste in stores. According to my mother, I would see one toy, then a second, then a third. I would then say, ‘Mama, let’s buy the entire shop.’ However, I would only ever receive one toy and soon forgot about the others.

I must confess that my love of things has remained with me to this very day. Another time, I was walking past the same store and ran up to my own reflection in one of their large mirrors. I was very disappointed that the ‘little girl’ did not wish to return my handshake and to make friends.

I was an only child and was told that I brought my parents much joy and happiness. I cannot remember my parents punishing me for anything but my father’s authority was paramount. I tried never to disappoint him. He loved me very much and Mama always remained sweet and loving, dedicating her life fully to Papa and me. It was said that I was my father’s daughter. Mama seemed neither offended nor jealous and did not try to win my affection and love. She did not try to bribe me with toys or treats but was simply, without heightened emotions, a gentle and loving mother.

Papa was more emotional. He was very loving and sensitive and reacted to jokes. He was also prepared to be the butt of jokes and during, particularly touching times, was able to shed a tear. He was never embarrassed to show his emotions.

Galina, age 6. First day of school.

Many years later, my daughter Marina wrote about her grandfather:

My grandfather, Ignatii KallinikovichVolegov, was a White Army officer who died still loyal to his oath: ‘For God, the Czar and the Fatherland’. He was also the only person who refused to drink to Stalin at a reception in China, and survived.

He did not justify his choices in life through hate and although he was very much an anti-Communist he retained a love for his country and the people in it. He never joined any organisations which would have harmed the Russian people in Russia, nor did he berate, those who stayed in Russia. He shared her suffering. He did not feel threatened by acknowledging anything positive that may have come from post revolutionary Russia.

In our home criticism of the long-suffering Russian Church, zloradstvie (joy) at the trials inflicted on the Russian people was anathema. It was unnecessary. I remember my grandfather as a man so confident in himself that he could allow himself to cry if something touched him. He was man enough to apologise, even to a child, if he felt it necessary. He was accepting and I could talk to him about everything that mattered, even The Beatles. In Bernard Shaw’s play, ‘Pygmalion’, it is said that a lady is a lady not by the way she behaves, but by the way she is treated.

My grandfather knew how to treat a child with respect and in doing so laid the foundation for the way I have always, though not always successfully, tried to behave.

The children of Hailar experienced never-ending fun in the summer and winter months.

In the winter, we had our very own ice rinks on two rivers. I remember coming home from school, grabbing a quick bite to eat and then running to the ice rinkd to skate before sundown. Papa built up a small snow hill in the backyard and children from the entire street would come to toboggan down the hill. The boys did this while standing on their toboggans but I was a chicken and went down either sitting or on my stomach. What a wonderful time of pure unadulterated childhood joy.

In the summer, we would swim in three large rivers - usually without adults. The rivers were quiet, shallow and clean. There were bushes along the banks. I loved to bathe, to read and to wash our clothes and then drape them on the bushes. Everything dried quickly and we returned home clean, fresh and having had a great deal of enjoyment from the water, the sand and having spent time in the company of friends. What joy – bathing in the water and playing on the shore.

Although I loved going to the river, I never did learn to swim properly - which brings me to my next story ...

One day, I went to the river to bathe with my cousin Vera. Vera was a very daring girl who was very spoilt by her parents. She did not recognise any limits and was never punished by her parents. She did whatever she wanted. She was older than me by three years and I naturally wanted to play with her and her friends. They were not too willing to include me in their games, however.

Vera always presented me with certain conditions and gave me the most demeaning roles in her games. If we were putting on a show in the backyard, a show where the audience consisted on neighbourhood children, I was always given the role of a silent flower. I was not allowed to say one word. I would start feeling sorry for myself whilst ‘on stage’ and start crying.

If Vera and her friends decided to play actresses, Vera was always Marlene Dietrich. The other girls would choose roles according to their tastes. I could only become part of the game if I took on the role of a poor actress wearing, in Vera’s words, ‘a torn beret’, who had lost everything. I agreed, if only to be allowed to play with them.

So, on this terrible day, Vera came to take me to the river to bathe. In order to get from one river to another, one needed to pass the first river by walking on the right side of the bridge. No one wanted to walk across the river, on the left side of the bridge, as it was too deep but Vera, however, was fearless and accepted the challenge. Of course, I had to follow her.

Just as I nearly reached the bank, I suddenly fell into a large hole. Luckily, a family friend named Tatiana Andreevna Kataeva happened to be walking along the banks of the river. She heard Vera calling, ‘Help!’ and rushed over. At first, she grabbed me by my hair and by my dress but I slipped out of her hands. She tried again and again. After what felt like a lifetime, Tatiana finally pulled me out of the water. What did she end up telling my mother?

I came home timidly. My mother told me off for being late. Having changed into dry clothes I lay on the bed with my favourite grandmother, who was visiting us at the time and said to her, ‘Babusia, I have drunk so much water.’

My grandmother understood everything and believed that what I said about having nearly drowned was true. She told my mother. Tatiana Andreevna said that she only managed to save me on her third attempt. If she had not managed I would have drowned.

After this, I lost all desire to learn to swim properly. I can stay afloat and can even swim a little. But, should I imagine that under me there is no bottom, I panic.

Ours was a very traditional family. As a child I felt that my heart beat in unison with the events that were being celebrated by the Church as we participated in all the Church Feasts and honoured the traditions that were connected with them.

Galina with her parents, Marina and Fr. Andrew Katkoff

Great Lent, Passion Week, Confession and Communion - the entire school or class prepared together and shared the experience.

The feelings of reverence and full immersion in the events leading up to the sufferings of Christ, their culmination during the services of Holy Thursday and Good Friday to the joy of hearing the words, ‘Christ is Risen!’ at the midnight Pascal service. I was really in the moment. I felt that Christ rose, ‘Now, at this very moment.’ I trembled and a feeling of deep joy filled my child’s soul, my eyes were filled with tears and I felt with my heart the presence of the risen Christ. As an adult I miss experiencing this heightened spiritual awareness.

Preparation for Christmas began several weeks before the Feast with the making of pelmeni (dumplings). In our small town of Hailar, everyone knew at whose place the pelmeni were being made so friends arranged working bees at each other’s houses. It became a pleasant but necessary chore.

We children loved these types of working bees. Although we were not actually allowed to make the pelmeni, we were allowed to roll out the dough. We were pleased to be allowed to participate and to listen in to the adult conversation.

The finished pelmeni were frozen and poured into bags. Enough were made to last until Theophany, the period known as sviatki. Even without freezers, in China as in Russia itself, pelmeni were kept frozen in the larder. Our storeroom had a large tub lined with a linen bag into which the pelmeni were poured. We used to go down with a large scoop or a deep dish and scoop up the pelmeni to be boiled and enjoyed.

Now, 40-50 years later, living in Australia, we continue to enjoy pelmeni and have introduced them to our Australian friends for whom this simple dish has become a delicacy. Meat and poultry was bought. Various delicacies were prepared – sausages, jellied meats and pates.

Closer to the day, tortes and cakes were baked. Houses were cleaned and decorated. Curtains were taken down and together with tablecloths and napkins were laundered. Given the freezing weather during that time of the year, this was no easy task. Everything was hung out on ropes in the courtyard. All the laundry froze and was brought into the house for the night as it could be stolen. Our home felt cosy, filled with the fresh fragrance of the fir (Christmas) tree.

On Christmas Eve, while I was in a deep sleep, the decorated Christmas tree appeared. For a long time I was sure that it was brought by Grandfather Frost, yet even when I was certain that a loving Mama and Papa did all, I preferred to cling to the illusion – still trying to continue the fairytale, still wanting to believe in Grandfather Frost.

Early Christmas morning, young children, usually boys, came to sing carols. The night before, Mama prepared small coins, lollies, nuts and other treats and these gifts were distributed to the various groups of children who came throughout the morning.

From morning, the table was set with festive food – a smorgasbord of savoury delicacies, wines, cakes and sweets. Viziteri (visitors comprising husbands and male friends) started arriving around midday. The tradition of entertaining viziteri was in all families – rich and poor.

The lady of the house prepared a feast according to her means, but each table reflected the joy of the occasion. The men went from house to house and visited the ladies. The ladies welcomed them and accepted their congratulations on the Feast. The men stayed long enough to toast the special day with a drink followed by a little to eat and would then hurry off to repeat the same at the house of the next lady. By evening there was quite a competition between the ladies as each counted up how many viziteri she had throughout the day.

On the first day of Christmas or Pascha (Easter), the priest and members of the choir would usually visit each home and conduct a short service culminating in a particularly joyous singing of the Troparion (festive hymn). These wonderful moments will never be forgotten and will continue to warm my heart. I will forever admire how carefully my parents preserved and passed on these traditions.

In the evening on Christmas Day, new, this time older, carol singers came carrying a large paper star of different colours. In the star there burned a candle before a picture of Christ in the manger and the children of the house joined the carollers in the singing of festive hymns and carols. They were also given money and treats.

The second day was the day when ladies made visits to each other. However, these would often end up in one house as many found it difficult to curtail their conversations once they got together over tea. In the evening the ladies were joined by their husbands and the table was set for dinner.

Christmas was celebrated up to the Feast of Theophany (the Baptism of Christ) and Easter up to the Feast of the Ascension, or in some places to Pentecost, also known as Trinity Sunday. So, from the second or third day of Christmas, the children’s parties began.

In each house, rich or poor, there was always a Christmas tree and someone dressed as Grandfather Frost. There were party games and each child received an individual bag from Grandfather Frost. Each bag mostly contained a mandarin, an apple, nuts, lollies and biscuits. Each child had to say a poem before receiving the gift and I remember clearly with what trepidation I approached Grandfather Frost.

The children were dressed in their best clothes and always wore party hats made by the loving hands of their mothers. These Christmas parties were an everyday event right through to Theophany because each mother organised a party for her own child.

As it was winter, apples and mandarins were bought earlier and were kept in the cellar till they were needed. The bags often contained a toy, crackers and sparklers. At sundown each mother would come to collect her child. With Theophany, the partying concluded and normal life began, and for the children – school.

The celebration of the Feast of Our Lord’s Theophany (the Baptism of Jesus at the river Jordan by St John the Baptist) was very special.

There were two churches in Hailar. After the Divine Liturgy, there was a procession from these churches to the ice filled river where a cross and an altar table were sculpted out of ice. A festive service in celebration of the Baptism of Christ was served.

During the singing of the Troparion, doves were released. Young boys would hold the homing pigeons and wait for the words, ‘And the Spirit in the form of a dove confirmed the certainty of the Word’, to let them go. In his book, ‘White Harbin’, G.B. Melihov writes, ‘From 1921, the blessing of the waters was done on the Sungari river which became for the faithful the river Jordan.

After Divine Liturgy, the clergy and parishioners from all the Harbin churches would go in procession to the river. A font was cut out of the ice and many young bravehearts bathed in the icy baptismal waters.

Many years later, when I lived in Harbin, I always went to the blessing of the waters at the river Sungari. It was very joyful. The procession from the Iversky Church, Sts Peter and Paul Church made its way to the St. Sofia Cathedral.

There, the two groups were joined together into one large procession and made their way to the Blagoveshenski Church (The Church of the Annunciation) where they were joined in turn by the parishioners from the Church of the Prophet Elijah. Here, they met the people from the St. Nicholas Church with banners, singing, the ringing of bells and golden clad icons. The atmosphere was amazing. The reflected sun’s rays from the snow and the eight-sided ice cross-created a phenomenal picture.

The sight of such a great mass of people moving along the Chinese streets towards the bank of the river Sungari is impossible to forget. The big joyous flow of people approaches the ice altar.

Even now, Harbin is noted for its magnificent Ice Festival. Its ice sculptures include an enormous cross, Royal Doors shaped in the form of an arch and decorated with two doves, a candle stand, and a pool-font in the shape of a cross for the believer bathers.

The sacred moment arrives when, singing the Troparion hymn:

When Thou was baptized in the Jordan, O Lord, the worship of the Trinity was made manifest; for the voice of the Father bore witness to Thee, calling Thee His beloved Son. And the Spirit in the form of a dove confirmed the certainty of the word. O Christ our God, Who has appeared and has enlightened the world, glory to Thee.

The priest lowers a cross into the font and blesses the water. The thin layer of ice separating the pool-font is broken and water gushes in. At that moment doves circle the Sungari/Jordan river. Many, including me, bathed in the icy water. Straw was laid around the pool to prevent the wet feet from freezing to the ice. Making the sign of the cross, one lowered oneself into the water three times. There were always people to help bathers emerge from the pool to avoid slipping.

Naturally, one dressed appropriately for this. A towelling robe covered the still wet swimsuit. One needed to somehow take off the swimsuit whilst keeping ones dignity in front of all the people. Then there was the shawl, fur coat and home on a rickshaw. Churches away from the Sungari river also constructed special ‘Jordans’, making a small font and erecting an ice cross for the blessing of the waters. Many years later, in 1988, the Lord granted me the opportunity to immerse myself into the river Jordan in the Holy Land.

The flow of people from the Theophany procession interfered with the normal flow of traffic. Because of this, the city transport system changed its timetable. Although there were traffic jams in different parts of the city, order was maintained by the Chinese police who formed a human chain, guarding the Theophany procession for its entire progress.

We left Harbin in 1957 and this tradition continued even after our departure. Many Chinese people also went to the Sungari with buckets and I remember asking one man why he was taking this water home.

‘Madam, can’t you understand anything. If you drink this water, you will not be sick,’ he answered.

I do not remember my parents talking to me about things spiritual – nor did they attempt to impose their opinions onto me – but the picture of family life, the behaviour of my parents, their regular attendance at church, and their performance of rituals and traditions confirmed in me a faith.

A big influence on me and on my spiritual development was Fr. Rostislav Gan. He was our pastor, parish priest and family friend. Again, it was not his sermons, which could not be fully grasped by a child’s mind, but the person of the priest, which influenced my view of the world and my spiritual growth.

Easter had a greater meaning for me than the Feast of the Nativity (Christmas), even though Christmas was always considered the ‘children’s Feast’. We prepared for Easter with Great Lent.

The week before the beginning of Lent, we celebrated Maslenitsia (Pancake Week). We enjoyed different types of pancakes, topped with sour cream, sturgeon, caviar, herring, jam etc. Then came Forgiveness Sunday ...

On this day, the Sunday Liturgy was always followed by a Vespers service, during which Fr. Rostislav would deliver a strict sermon on the nature of fasting, repentance, forgiveness and reconciliation. The priest would then ask forgiveness from the entire congregation and the members of the congregation would ask forgiveness from each other. There was a general reconciliation within the church and at home amongst members of the family. However, the next day, on the first Monday of Great Lent, the atmosphere completely changes. There are no more dances or concerts. The church takes on a sombre look. The vestments worn by the clergy are now black with white crosses.

During Lent, students go to church for confession and then again to Holy Communion on the following day.

As students, we loved Palm Sunday. We respectfully stood in church in the evening, holding bunches of pussy willow, decorated with paper flowers and candles.

Holy Week was the most difficult week of Great Lent. Naturally, because of school, we could not attend all the unceasing morning and evening services that were scheduled. However, the services of Holy Thursday, including the Reading of the 12 Gospels as well as the Burial Services on Holy (Good) Friday were never missed. Following the service of the 12 Gospels, people took home the lit candle that they had been holding during the service. They went from room to room and made a sign of the cross on the beam of each door of their house.

Many years later, I was in Moscow in 1992 and by old tradition brought the lit candle to the home where I was staying. This surprised my friends because this tradition had not been followed during Soviet times.

On Good Friday, very emotional services take place - vinos plashenitsi (the taking down from the Cross) and pogrebenie (the Lamentations). The dimly lit church, with its sombre singing and readings on the Passion of Our Lord, creates a full picture of the tragedy of what occurred. We would return home, with bowed heads, concentrating on the full impact of the sufferings of Christ. But then, Paskha arrives ...

The church is brightly lit with chandeliers and candles. The dark coverings and vestments are replaced with white. ‘Christ is Risen!’ and ‘He is Risen Indeed!’ echoes through the church. All are joyous, smiling and happy.

I still remember our last Pashal service in the St. Nicholas Cathedral in Harbin. Metropolitan Nestor served as hierarchy of the Moscow Patriarchate. Co-serving were Bishop Nikandr and a number of priests. I remember how Bishop Nestor, with each cry of ‘Christ if Risen!’ lifted his hand with candles and we could see all the colours of the rainbow reflected from his crystal rosary beads. This detail has remained with me all these years.

Bishop Nikandr Leonidov

After the service, we went home and broke the fast and in the morning the ladies of the house prepared to receive their visiteri.

With the joy of Easter came much work for our mothers especially when they embarked on the sacred duty of baking the kulichi (Easter cakes). All the ingredients were prepared earlier. Mama was preoccupied for several days before baking day. Discussions were held with her sister, Alexandra Fedorovna Lupova (with whom they shared a very close friendship). They had to decide whether to bake the kulichi in their own ovens or to take them to the Chinese bakers who provided their ovens for a nominal fee.

I loved the whole preparation process because nuts and sultanas needed to be sorted. Almonds were covered with hot water to remove the skins; while sultanas were washed to remove dust and sand. Large towels were spread on tables for the sultanas and almonds. How delicious it was to sneak a sultana or almond with Mama pretending not to notice.

The leaven was started at night and from that time to the time that the last kulich was taken out of the oven, women did not have any peace. Concerned faces, eyes full of fear, ‘What if the dough does not rise?’ So many ingredients could be ruined. So much worry!

Doors were opened and closed quietly. On no account could you bang the door. The dough could sink. Then, the magic moment. The last kulich is taken out of the oven, Mama is glowing, Aunt Shura is happy and everything else – is nothing.

After surviving the baking of the kulichi, the tortes, biscuits and other foods are not a problem. The decoration of the cakes and the colouring of the eggs were all a very important part of the preparation and setting of the festive Easter table. Here, the artistry of each housekeeper came to the fore.

Later in Australia, during my long service leave following 25 years work in the hospital, I took a course with Vera Stepanovna Apanaskevich in the special art of cake and kulichi decoration. I learned how to make fruit jellies and zefir (marshmellow). Unfortunately, calories proved to be a problem. Roses, mushrooms with chocolate tops, flowers etc. made from butter-cream may have looked good but were unhealthy so this art was not used often. However, I did make my daughter’s wedding cake when she married Vasia and decorated Christening cakes for my grandchildren.

It is important to describe how Radonitsa (remembrance of those who died) was celebrated in Harbin. On the tenth day after Paskha, on Tuesday, all Orthodox churches would conduct a general Panikhida (Memorial Service). After the Panikhida the clergy and people made their way to the Uspensky cemetery where shorter, individual services were held at each grave.

According to old Russian custom, it was usual to bring kutia (a bowl of sweetened rice or other grain usually decorated with dried fruit), food and something to drink. People would in this way pray for and remember the departed at the grave site. Special buses were often used and the local authorities ensured that buses, trams and pedestrians all moved in an orderly fashion.

It is sad to note that the Uspensky (Dormition) Cathedral and the cemetery were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. The memorial stones were then used to pave the streets and the cemetery was razed to become a park. People said that when walking along the streets of Harbin it was sometimes possible to see the names of loved ones and acquaintances among the stones embedded in the paths and roads. These were the grimaces of fate that life presented during the days of ‘great changes’ which took away and destroyed millions of innocent people in jails, camps and exile.