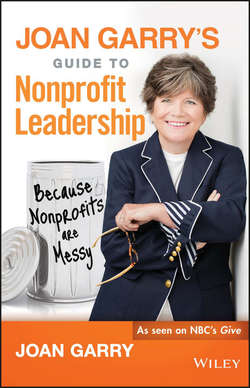

Читать книгу Joan Garry's Guide to Nonprofit Leadership - Garry Joan - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 1

THE SUPERPOWERS OF NONPROFIT LEADERSHIP

ОглавлениеDear Joan:

I've been with my organization for nearly eight years, most recently in a development role. My predecessor has been the voice and face of the organization for nearly 25 years and has just retired. The board has offered me the E.D. position.

This would be alien territory for me. I've been the relationship guy and I keep the trains running on time.

And the truth is I'm not exactly sure what I would be getting into. I want to give this a go but I think I need help and would like to retain you as a coach.

My goal is simple: I want to learn to behave like an executive director.

Signed,

E.D. “E.T.”

“To behave like an executive director.” A very good goal for an executive director, I might add.

E.T. became a client and we teased out exactly what he meant by this.

To be a leader and not a department head. To worry about the whole organization and every stakeholder. To stare at cash flow and wonder about payroll. To take responsibility for partnering with the board so that its members can fulfill their obligations. To stand up at a gala and give an inspiring and motivating speech. To feel an overwhelming sense of responsibility for the communities you serve.

It's a hard role and a hard role to cast for. I am currently working with a board that cannot agree on the role the executive director should play (and they are already interviewing candidates!). (Can you say, “Cart before the horse”?)

Who should a board be looking for? What matters? In small organizations, the staff leader really does do it all. A person who can inspire a group with her words and read a balance sheet? What skills and attributes matter? Do you have them? How do you cultivate them?

And the decision is so important. In my experience, leadership transitions are the most destabilizing forces in a nonprofit organization. Try raising money when you are between executive directors. 'Nuff said.

What's interesting is that all these same issues and questions apply to board chairs as well. What should an organization be looking for in a board chair? (Note: the correct answer is not “Pray that someone raises her hand and pick her.”) How might the skills and attributes of that person complement those of the staff leader? What skills and attributes matter? How do you cultivate them?

A Quiz

Before I give you the answer to these questions, let's try a little quiz. Are you currently a nonprofit E.D., overwhelmed by the idea that you need to be all things to all people? A board chair enthusiastic about leading the board to support the staff? Or someone who aspires to change the world and make the for-profit to nonprofit leap?

The quiz should put things into perspective and begin to reveal the superpowers.

So riddle me this, Batmen and – women, it's time to pick your next board chair or executive director. Here are the finalists:

• Superman

• Spiderman

• Gumby

• Kermit the Frog

Let's dissect this, shall we? (Oh, apologies to Kermit – not a good word for frogs.)

Each of these four have amazing strengths. Perhaps at first blush, you figure any of them could be a five-star nonprofit leader.

Superman?

This guy has some serious things going for him:

• Sometimes organizations just want someone to swoop in and save the day.

• He's dripping with integrity and tells the truth.

• He is very smart.

• Would you say, “No” to him if he asked you for a donation?

• He has a fabulous outfit (I hear capes might be coming back).

Spiderman?

Lots of appeal here, too. He's human, powerful, and nerdy. He's vulnerable but strong. Some comic book fanatics say he is the single greatest superhero of them all.

• He has real humanity – vulnerabilities, guilt, and flaws.

• He's driven. Peter Parker, the man behind Spiderman, helps people because he understands the price of not doing it – he could have prevented his uncle's death.

• He grows into his power. The responsibility of leadership is not something he asks for but he accepts it and uses that responsibility to the best of his ability.

Gumby?

One of my senior staff members gave me a small Gumby figure I have right here on my desk. When I look at him, I am reminded that not everything is black and white and that being flexible is absolutely key to success in any setting. Is Gumby your man?

• He's well rounded.

• Very optimistic – would lead with an optimism that his organization could change the world.

• He's someone you want to be around – kind, warm-hearted, and generous.

• He has real humanity – vulnerabilities, guilt, and flaws.

Kermit?

Another guy with some solid skills and attributes for nonprofit leadership:

• A team builder. He can bring a diverse group together. Anyone who can get Gonzo, Fozzie, and Miss Piggy working toward a common goal has a real superpower.

• Kermit is an optimist but not a Pollyanna. He can get down sometimes too, but in the end, he has a vision and rallies the Muppets around it.

• He cares deeply about doing the right thing.

• Kermit is your go-to guy in a crisis.

• Strong planning skills.

• His ego is just the right size – he can and does admit mistakes.

Time to put the four of them to the test. Here's the kind of situation each of them may encounter. Then you get to make your choice.

You need a new board chair. The previous leader didn't want the job – might have been in the restroom during elections. Committees are dormant. The board does a decent job selling tickets to your big gala but half of them don't want to pay for a ticket themselves. The founder of the organization is a big personality and when she stepped down two years ago, she offered to join the board and your previous board chair couldn't say no. She isn't letting go of the job. Your E.D. is a good performer but the founder is driving her mad. You are worried she may be recruited away.

Who is the guy for the job? (I just grabbed a few superhero prototypes – there are lots of great women leaders out there, too.)

Superman is the command-and-control nonprofit leader. The world is quite black and white for him. He would see board members as “good guys” or “bad guys.” We know the world is not that simple. Nonprofit leadership demands both an understanding and an appreciation for nuance and the land of the gray. We know this type. A good leader to dig you out fast, but not the marathon guy.

Spiderman is a more empathetic, three-dimensional leader. His downfall is the challenge of many leaders —insecurity.

Gumby? What a nice guy. Who would not want to sit and hear about an organization from somebody like Gumby? He is a relationship builder of the highest order. But his fatal leadership flaw? He is a pleaser. Now most nonprofit leaders have some pleaser stuff going on. But if it drives you, you are done for. You have various stakeholders and pleasing everyone usually means pleasing no one. And your job isn't about pleasing. It's about serving your mission.

Okay. So I've given the answer away.

My vote goes to Kermit, hands down.

First off, Kermit would have figured out some way to give the founder a big role with no real power. Look how he manages Piggy. He would rally the troops without shaming them. He would find the key strength in each board member and bring out the best in each of them. He would not be overly bossy with the E.D. – he'd offer his support and be more like a coach. And he would help staff and board keep their eyes on the prize, never losing sight of the organization's mission and vision.

Kermit may not thrive in a hierarchical work environment but he'd be a rock star E.D. or board chair.

Kermit is not perfect and he knows it. But so key to effective leadership, it makes him a good delegator! He is all about the team and he understands the value each brings to the work. He believes in diversity. He likes to work to reach consensus but never loses sight of the end game – he is always true to the cause. He is fair and listens and he can manage high-maintenance personalities without sacrificing the work. I also think he can disagree and his team ultimately listens and respects the decision (the decision they feel was made with their input).

He understands what it takes to be a great leader in the nonprofit sector.

He understands that power comes from all around you.

He recognizes that developing core leadership attributes is as important as skills building.

You're Not on Top of Anything

In 1997, the Coors Brewing Company approached me, as the executive director of GLAAD. They were interested in making a $50,000 corporate sponsorship donation to our organization. As our organization was still on a financial respirator, I was interested. Very interested.

But I knew the history of Coors and the gay community – the Coors family had deep ties to the Heritage Foundation, a significant funder of organizations leading the opposition to LGBT equality. As a result, there had been a longstanding boycott in the gay community. Drink any beer you like but not Coors.

A discussion with Coors illustrated to me that the company was better on gay issues inside its organization (domestic partner benefits and other nondiscrimination policies) than many other companies that supported GLAAD.

Should I accept the sponsorship money and in so doing help rebuild the Coors brand in the gay community? The decision was mine to make.

Or was it?

In Jim Collins's monograph From Good to Great in the Social Sector, he makes the case that power and decision making in the nonprofit sector is different from (and messier than) how it is in the private sector.

To be a great leader, you must erase your preconceived notions of what it means to be in charge, and this starts with a standard organizational chart (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The basic org chart we all know and understand.

Power and Authority

You probably have a piece of paper that shows this kind of hierarchy. Time to recycle.

Is it factually accurate? Yup. Is it how you should look at or exert your power as a nonprofit leader? Absolutely not.

Now take a look at the chart shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Picture it this way instead. The power comes from around you.

Using the org chart in Figure 1.1, the Coors decision is easy. I make a statement about the changes at Coors, accept the donation, make payroll, and let the chips fall where they may.

In the nonprofit sector, a leader is beholden to vast and diverse stakeholders. I was hired to run GLAAD in the service of moving the needle forward on equal rights for the community I served. The bottom line matters, of course, but only to ensure that you have sufficient resources to work in the service of your mission.

In the org chart in Figure 1.2, the executive director derives power from all around her. This is why former Girl Scout E.D. Frances Hesselbein once told a reporter that she saw herself in the center and that she “was not on top of anything.”

So what did this mean for the Coors decision? The voices of the stakeholder groups around me were critical. I needed to be well informed, I needed strong input from different groups, and I needed a thought partner in my board chair to kick around the pros and cons. I knew the decision was ultimately mine but I never really thought of it that way. We were all in this together.

My development director (the one I nearly killed – see the intro) was outraged and feared we would lose more money than we earned by accepting Coors' donation. We did our due diligence and determined that would not be the case. The staff was mixed – some worried I would be eaten alive by the press (given my own corporate background) either way; others thought rejecting the money could be unfair to Coors when in fact, by corporate standards, they were leaders on gay issues.

This kind of power demands that you meet with the leaders of the Coors Boycott Committee – not to empower them but to ensure their voices are heard. We even invited them to a board meeting.

And this kind of power demands that you see the decision from all sides. We secured a meeting with the most senior people at Coors and garnered commitments from them to do more than just donate money.

And this kind of power demanded that I put myself at a national LGBT conference in which several hundred community members could share their distaste with the thought that GLAAD may make this choice. In this setting, you can be sure that I heard them. Many of them were yelling at me.

In the end, Coors became a corporate sponsor of GLAAD. Not everyone agreed but everyone had a voice. All stakeholder groups were heard and our entire process and strategy was smarter and more effective than any decision I had made on my own. This is what Jim Collins means when he talks about power in the nonprofit sector being “diffuse.” And at its best, it creates a staff that feels valued and heard, a supportive board comfortable with challenging, and a membership that sees a process rich with integrity.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу