Читать книгу The Museum of Lost Love - Gary Barker - Страница 9

Оглавление-

Katia

Katia knew that look in her patients’ eyes. She had questioned the competence of her own therapist. In her case it had been a woman, black like her, when she was fifteen. Now, as she started her own practice, the patients came to her instead. And she was convinced their lives were bigger and more damaged than her own.

She was silent as she sat across from her first patient of the day, a man about her age. He had short, tussled blond hair, his weathered skin affirming the hours he spent outdoors.

Katia wanted to throw her notepad at him: Say something, will you?! This doesn’t work unless you help me here. This was their second session and both fidgeted as if on an internet-arranged date.

“Mr. Nielsen, how is your son adjusting?”

“You can call me Tyler. Mr. Nielsen sounds like my dad’s name.”

“How so?”

“I’m usually Officer Nielsen. Then I was Corporal Nielsen. But I’ve never really been Mr. Nielsen. Just Tyler.”

“And now you’re the dad.”

“Sammy doesn’t call me that.”

“No, not yet, I’m sure. But he will.”

Tyler stopped. He hunched his shoulders slightly as if confessing. This is how it went with him. He would start, stingily offer a few details, then stop again, staring at the floor or at his interlaced fingers. Seeing him like this, it was hard for her to imagine how he must have been when on patrol, with his uniform, his gun, his broad shoulders and muscular arms commanding respect.

Katia had asked her clinical supervisor about Tyler’s long silences. Just let him be. If it goes on too long, ask him again if he wants to continue seeing you. And if he says yes, let the minutes go. Ask some questions but not too many. If it goes on like that, I would say you stop the session after fifteen or twenty minutes and suggest to him that you start again the next week.

Katia lost her concentration when he stopped like this. She thought about her recent move to Austin, her other clients, and whether Goran would call. Whether she wanted him to call. Whether she missed him. Or whether she was glad they were in this extended period of undefined, long-distance whatever and that he was a safe distance away in the apartment they had once shared in Chicago.

“I’m worried about what I’m starting to feel and if it’ll confuse him.”

Tyler’s voice seemed to come from the next room or the next building, from down the street. The words snaked their way into the quiet of the consultation room. It took Katia a moment to re-engage.

“What is it you’re starting to feel?”

“For this woman I met. It’s like my boy just came into my life. I never even knew I had a son until now. And just when I’m figuring out how to get on with him, I meet this woman.”

“Do you want to talk about her?”

“It’s not about her, or who she is really. It’s about that feeling, if you know what I mean.”

Katia knew she should wait for him to say more, but the halting flow of Tyler’s words was unbearable.

“Tell me about that feeling.”

Tyler took a deep breath and stared at her with exasperation.

“It’s like Afghanistan. Like being on those patrols. At night. Even with night gear and all. I mean even in the daytime in Afghanistan it’s like you’re blind. You have no idea when they’ll hit you or what they’ll hit you with or who’s out there. If they’re Taliban or just some goat herder and his family getting on with their day. Every time you come around a blind spot or a corner, every step, you’re ready for that explosion. Direct or indirect. It’s all the same. That’s how I feel with a woman when I’m starting to care about her, you know. It’s like love is … like I’m completely blind.”

Katia repressed a smile. Only occasionally did Tyler use so many words. She struggled not to hum the rest of the song that jumped into her head, and not to tell Tyler her own story. She knew that wasn’t allowed, and she knew this wasn’t about her.

“Sammy cries at night. He calls out for her, you know, for his mother.”

“Does Sammy ever talk about her?”

“Not really. Only if I ask him.”

“And, how do you feel about what Sammy’s mother did?”

“I don’t know what to make of it.”

Katia waited again for him to say more but she did not insist. Neither did he say anything more about the woman he had just met. She let that go too. It was enough that he was using so many words. In the end, she was relieved that they had made it through this second session.

As Tyler closed the door to the consultation room, Katia moved to her desk and opened her laptop. With one part of her brain she wrote up the notes from the session. The other part was thinking about that song. And that made her think about Goran.

Love is blindness. I don’t want to see. Won’t you wrap the night around me … Oh, my heart. Love is blindness.

◆ ◆ ◆

“We should go here,” Goran had said that morning, more than a year before Katia had moved to Austin. “We have a day in Zagreb before we leave for the coast.”

They were sitting at the kitchen table in the small apartment near the university, where Goran worked. It still felt like his apartment, even though she had moved in with him a few weeks back. He handed her the New York Times Sunday travel section. Katia took a few minutes to read a short article describing the museum where people sent letters of love lost and ended.

“Sure, I guess. Sounds a little melancholic though,” Katia said.

“We’re a melancholic people,” Goran said, smiling joyfully. He slid his right forearm across the small table to her right forearm and grasped gently. She felt safe like this, their arms interlaced, just as she had with every decision that had led her here, to move in with him.

They went back to reading their respective sections of the Times. He asked her if she wanted more coffee and he got up to make it. As he set her cup in front of her, he ran his fingers down her neck. It was one of things that had first attracted her to him, his long, elegant fingers. Katia turned the palm of his right hand up and kissed it and then pulled it under her robe.

This is what they could be. What they were. What she imagined they would remain. She believed they were on a path that would take them from I-hardly-know-you to I-feel-like-I’ve-always-known-you. Katia had let go of her skepticism for long enough to believe that what they had was an open-ended parenthesis with no sign of closing.

Two weeks later they arrived in Zagreb late at night and checked into their hotel room, exhausted after the flights. Drifting into sleep, they rolled into each other in the middle of the sagging bed. It was late in the morning when she woke him up by running her hand along his arm. Her lips lightly touched his shoulder.

As they slowly emerged from their sleep, the only light was a thin white line coming through underneath the door. With her nose resting at the back of his neck, Goran’s smell was familiar. Freshly cut wood mixed with a slight scent of sweat. This grounded her. She was glad the room had no distinct smell that distracted her from his.

They were mostly silent over what remained of the breakfast buffet in the ground-floor hotel dining area. All of it was pleasantly far from Chicago and from classes and term papers. Both could tell the other was enjoying being away from their daily routine.

They continued their silence as they walked the cobblestone streets through the upper, old city of Zagreb to the museum. Freed from their heavy winter coats, they held hands and let their arms sway as if they were only loosely connected to their bodies. The mid-morning air was comfortably cool, the sun shining with the promise of heat.

Goran looked at home here with his fair skin and straight, dark hair and a seriousness that in an instant could give way to his Balkan joviality. Katia, with skin the color of caffe latte and a long afro, stood out. They leaned into each other as they found the street where the hotel concierge had said the museum was, bracketed by a baroque church and a Greek orthodox seminary. Goran held the door open for her while still holding her hand. Normally Katia didn’t like these overt displays of affection, but here she followed his lead.

He spoke in Croatian as he bought tickets from the young woman at the entrance. Then they stepped into a world of passion and love and sex gone wrong.

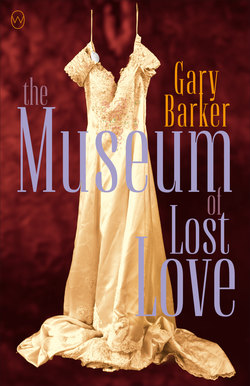

This was the place where the curators exhibited love’s detritus. There were wedding dresses and keys and dolls and stuffed animals and dildos; objects of affections lost and ended through deception and confusion and death and migration and dozens of other reasons known, unknown, or unclear.

After reading several of the letters together, they went in different directions. Goran was drawn to a trunk and a smashed statue in a glass case:

He was never the same after the earthquake. It was as if all he thought he could build for me and build to keep us safe could be broken. He pulled away from me and could not talk. He could not get beyond speaking only the basic things he needed to communicate just to live. It was the gardener who saw him leave. He told me he saw my husband lean down to pick up the pieces of this statue. The gardener said my husband began to cry and then walked away. He did not come back. He wrote months later with an address of where to send some of his things. As if I had been nothing but a landlady, or the manager of a warehouse for his belongings, for our twelve years together. He didn’t ask how I was. I didn’t tell him that I was pregnant when he left. I didn’t tell him about his daughter. He still does not know.

Kushiro, Japan, 2003

Katia was drawn to the corner with the sex toys, curious about the letters and stories that came with them. She read the letter next to a rabbit-shaped dildo:

We had seen each other at the pub on the corner near my flat and stopped to talk a couple of times. Then, that one Friday, we finally found ourselves sitting down for that drink we promised we would share one of these nights. It all happened without our having to say much. After drinks we went to my flat. She said the sex was amazing, that I was the first woman she had ever felt so free with. For that whole weekend we hardly got out of bed. I wondered if you could go crazy from amazing sex. I showed her my toys. She had this one in her purse. Then Monday came and we both had to go to work. I was sure when she called me at lunchtime that she would ask when we could get together again. That she missed me already. That she felt it too. She said I should know that she had a husband and that he couldn’t know about any of this and that it couldn’t happen again. She didn’t ask for her dildo back.

London, England, 2007

Each story compelled Katia to read the next one, to understand and feel the love and the hurt that went into each letter and accompanying object. Some had videos and pictures, and at times Katia felt she was invading the privacy of all these lives—that the writers of these letters would somehow feel her peering into their secrets.

Katia was so engrossed in the stories that she was slow to notice that Goran had been staring at the same exhibit for a long time. She became curious. Although she could only see Goran’s backside, she thought she could tell by his posture that he was somber as he read.

Katia walked toward Goran, and said nothing as she came up beside him, casually placing her hand on his shoulder. She moved her hand up past his shirt collar to his neck. Under the glass and next to the letter there was a CD case and next to that a drawing of a house and garden that looked as if it had been done by a child.

Katia carefully read the letter.

We were together for just two days. Two days all those years ago. And I have never gotten him out of my head. It sounds trite even as I write it. He is my first love and he probably doesn’t even know it. Our families were trying to get out at the same time. We were stuck in a transit camp, trying to leave at the beginning of the war.

It was very difficult to get out. You had to have papers in order, connections. Proof that no man in your family was running away from being drafted. Proof that you had somewhere to go. That some country, one not falling to pieces, would accept you.

We stayed up late into the night, all night, telling stories about our friends, our families, and our schools. He was fourteen. Nearly fifteen, he insisted. I was sixteen. He was so sweet, and so nervous. I could tell he had probably never talked like this with a girl before. He said he was sad that he had to leave his guitar behind.

He had a portable CD player with earphones and when we ran out of things to talk about, he put one earphone in my ear and the other in his and we listened to his CDs together. With his fingers he tapped the rhythm on my leg, pausing the CD and going back to lyrics that he wanted me to understand. His English was much better than mine and I could tell that he enjoyed being able to translate for me.

I took out the notebook I had in my backpack and showed him a drawing that I had made when I was younger of the cottage my grandparents had outside of Mostar. The notebook was one of the few things I was able to bring, apart from my clothes.

He saw me getting sad when I talked about the cottage, and about my grandparents, who were not going with us. He looked at me for a long time. Then he brushed the hair out of my eyes and ran his hand along my cheek. He moved his arm so our forearms were entwined. Then he brought his mouth to mine.

I wonder if he remembers that kiss. It was a kiss that carried my whole body with it. And I wonder if he remembers how safe he made me feel when he held my arm like that.

I wonder where he is now. His family was going to the US.

I wonder if he ever stays awake at night thinking about that kiss the way I do. I wonder if he knows that was the last time I felt safe.

Almost every day I wonder what has become of him. Whether he has children. Whether he is married. What he looks like as an adult. What kind of man he turned into. What his life is like.

This is all I have of that time: the drawing I did of my grandparents’ cottage and the CD he gave me to remember him by. U2’s Achtung Baby. Everybody liked “One” but he liked “Love Is Blindness.” He played the song for me, and read me the lyrics as if reciting a poem he had written himself.

I tried to give him the drawing of my grandparents’ cottage as my gift to him, but he refused. He said that the house might not be there when I came back after the war and that the drawing might be my only way to remember. For a moment he sounded so wise, much wiser than the fourteen-year-old boy that he was.

In the end he was right. My grandparents’ house did not survive the war.

He and his family made it out the next day. Mine never did.

Maybe I am sending this to see if he will find me. Mostly I think I am sending it so I will forget. Or at least think about him in a different way. In a way that doesn’t keep me awake at night. Or maybe I’m just sending these things because I don’t need them anymore.

Novi Grad, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1992, and Toronto, Canada, 2010

Katia thought she could hear two voices in her head: the voice of the young girl in the transit camp, and the voice of the adult woman looking back. She imagined herself having coffee with this woman, asking her about her life since the war and about the young man in the transit camp, whose family had left Bosnia around the same time Goran’s had.

Katia looked at him. Goran did not return her gaze. His eyes were focused on the CD cover. She saw that he was crying. It was endearing that Goran would be so moved by this, yet she knew him well enough to know that he was not easily driven to tears. Katia followed his eyes to the CD.

It was marked with initials. In a handwriting Katia had come to know, from notes left in her mailbox, or on the grocery list stuck to the refrigerator in the apartment, she saw the letters. GV.

Her GV. Goran Vukovic.

“Goran,” she said.

He did not answer.

“Goran?” she said again. “Is she talking about you?”

There was no reason to be jealous or insecure. Her tone was from curiosity and amazement that he, her Goran, would be part of this museum. And part of this woman’s life, and that this story had found him here, like this.

Goran started to answer. He turned to face Katia and she took her hand off his shoulder.

“Katia … I …” he started, his voice struggling to restrain emotion. “I had no idea this was here.”

“Goran, it’s amazing that this found you. You’ve never been in touch with her?”

He turned away from her.

“No, no, of course not. I had no way to find her and I didn’t even think she remembered. That was such a long time ago. I …”

Katia reached out gently with both of her hands to hold Goran’s arm: “You made her feel safe …”

Goran pulled his arm away and stared at her.

“It was more than that. It was the middle of a fucking war. People were doing anything to get out. You don’t know what that was like. We knew what they were doing to women and girls. Her family didn’t get out.”

“No, I guess I don’t understand. I didn’t live through the war.”

“No, you didn’t.”

“Take your time, Goran. I’ll wait for you in the café.”

His look told her he was relieved to have a moment to himself. She walked out the exit and entered the lobby.

From across the small gift shop, Katia watched other visitors coming into the museum. In the gift shop she glanced at the various objects for sale, all with designs featuring broken hearts and fractured lines. After another group of visitors entered and paid, Katia felt the woman who sold tickets looking at her. Whether here or back in the US, she was used to such stares.

“You have beautiful hair,” the woman said in slightly accented English.

“Thank you,” Katia replied.

She gave a quick, false smile to the woman, looked down, and then walked to the museum café and sat at a table in one corner. The waiter, a young man dressed in black pants and a black T-shirt, offered her a menu, and took her order.

While she waited for her coffee, Katia ran her finger around each of the buttons of her sweater, starting at the top and working down and then back up. She ordered a second double espresso. Although her back was toward the exit of the exhibition space, she could sense Goran walking toward her. She felt his hesitation. He knew that Katia wanted to know more about the girl in the camp. But even more, that she wanted to know why he had reacted that way.

◆ ◆ ◆

As Katia finished typing up her notes from her session with Tyler, she looked at her mobile phone. No missed calls, no texts.

With each day away from Goran she was learning this: the normal state of lovers, of couples, is not together. Together is a transient state. The normal state of things is as much about ending and leaving as it is about beginning and staying. The normal state of love is living with the possibility that everything can, at a moment’s notice, come tumbling down. We impossibly walk for some amount of time in the same pages, in the same narrative, and we deny with every breath the possibility, indeed the likelihood, that the arc of the story bends toward being alone.

Every city, Katia thought, every village, every neighborhood, should have a museum like the one Goran had taken her to visit more than a year ago. Children should be given classes in how to break up and move on. How to mourn the sudden loss of all-encompassing love or the end of an intense, fleeting affair and carry on with dignity. How to let someone get that close, know you that way, and let them go, taking with them your secret words and bedroom stories and those private little cries and tremors. How to walk into the story with kindness, and walk out of it without drawing blood.

Sometimes, when Katia found herself missing Goran and wondering what might be next, she looked at her phone and scrolled through the pictures she had taken of the letters and objects in the museum. Someday, she thought, she might submit one.