Читать книгу We Are Fighting the World - Gary Kynoch - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1 Urban Violence in South Africa

SOUTH AFRICA IS ONE OF the most crime-ridden societies in the world.1 In a country where unemployment runs between 30 and 50 percent and the majority of the population struggles on the economic margins, high crime rates are not surprising. It is the violence associated with so much of the crime that has created a climate of fear. Carjacking, rape, murder, armed robbery, gang conflicts, taxi wars, vigilantism, and police shootings dominate the headlines and the national consciousness. This culture of violence has become one of the defining features of contemporary South African life.

Although segregation and apartheid nurtured hostility and conflict among all population groups in South Africa, surprisingly little effort has been made to investigate the historical roots of the current crisis. To the extent that historical factors are considered, the epidemic of violent crime is most often attributed to the civil conflicts of the 1980s and 1990s. These conflicts—usually referred to as political violence—raged throughout many of South Africa’s urban townships as well as some rural areas. In 1985 the African National Congress (ANC) called on its supporters to make the townships ungovernable and urban violence escalated as thousands of activists heeded that call. The National Party (NP) government responded predictably, ordering the police and military to crush political dissent. Government security forces also encouraged various elements within the black population to take up arms against ANC militants, known as comrades. Once the ANC was unbanned in 1990 and elections loomed on the horizon, the violence intensified. Agents within the security apparatus sponsored and directly assisted the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), a “moderate,” ethnically Zulu political movement, in its war against the ANC and supported conservative black groups that refused to acknowledge the authority of the comrades. The South African Police (SAP) allowed criminal gangs to operate with impunity in return for their services as informants and assassins. All the warring parties recruited criminal gangs to some extent and were unable to exercise full control over the elements that fought in their name. Large parts of KwaZulu-Natal, along with many townships and informal settlements in other areas of the country, became war zones.

In conventional accounts this anarchic violence created a residuum of men, inured to killing, who have pursued purely criminal endeavors following the cessation of politically motivated hostilities.2 The youth who engaged in these conflicts are often referred to as the lost generation, partially because they sacrificed their education for the liberation struggle. Comrades who had been valorized for their role in the struggle felt betrayed by an ANC government that discarded them once it was voted into power. These men, and other combatants who had exploited the violence to achieve positions of power, continued with and expanded their predatory activities while shedding any pretense of political motivation. The current generation of South African youth has grown up with this legacy and embraced a criminal lifestyle. In this interpretation, the civil conflicts gave birth to a culture of violence and lawlessness that continues to haunt South Africa long after the political struggle was effectively settled by the ANC’s 1994 election victory.

This explanation is limited by its failure to consider the longer-term historical dimensions of the prevailing crisis. The fighting between government forces, the ANC, Inkatha, and their various proxies infused localized disputes with a political veneer and significantly escalated the scale of violence. However, these conflicts did not create a culture of violence in the townships. A historically grounded analysis clearly demonstrates that political rivalries degenerated into bloody conflicts partially because a culture of violence was already ingrained in township society. South Africa’s endemic violence, in other words, is not a post-conflict affair but rather a continuation of preexisting conditions.

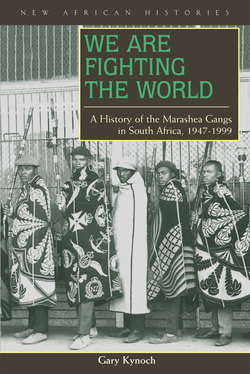

This book explores the nature of power and violence in the apartheid era through the history of the Marashea. In particular, this study counters the notion of apartheid as a systematic program of social engineering that regulated virtually every aspect of black urban life. The failure of the colonial state to control urban townships and informal settlements and to provide effective civil policing created the space and incentive for the emergence of various criminal and vigilante groups that proliferated during the turbulent decades of apartheid. Despite the battery of legislation introduced by the apartheid regime to further restrict the lives of black urbanites, the activities and interactions of criminal gangs and vigilantes were, in many respects, more instrumental than government policy in shaping the day-to-day lives of township residents. Gangster and vigilante violence, often exacerbated by a police force primarily concerned with enforcing racial legislation and suppressing political dissent, became a normative feature of life in many townships and a driving force behind the culture of violence that developed in South Africa. The shifting character of urban violence indicates the need to move beyond the resistance-collaboration binary that still defines much of South African social history. Organizations like the Marashea established, protected, and expanded spheres of influence independent of larger political and ideological concerns. Their actions were guided by immediate local interests that at certain times led to clashes with state forces and at others resulted in alliances with police and government officials. The resistance-collaboration dyad makes no allowances for this complexity and an approach that is sensitive to—yet not defined by—the struggle for liberation provides an improved understanding of the range of social relationships that developed under apartheid.

The title of this book, “We Are Fighting the World,” reflects Marashea members’ conviction that a range of forces were arrayed against them in the urban and mining environs of apartheid South Africa. Their collective story of survival reveals much about how Africans constructed their worlds within the structural constraints imposed by the white-ruled state. The relative autonomy of these gangs of migrant Basotho highlights the limitations of apartheid hegemony. The state simply never possessed the resources to effectively govern and control the urban areas designated for black settlement. At any given time the government could concentrate its forces and occupy a township or group of townships, but it was unable to maintain a constant presence. The Marashea was one of hundreds of African organizations that filled this void and shaped the experiences of township, mining hostel, and informal settlement residents. Apartheid, no less than other forms of colonial governance, was mediated by the Africans it was designed to subjugate and control. A system that denied black South Africans protective policing and access to an equitable justice system inevitably produced a variety of groups that attempted to fulfill these functions as well as those that capitalized on the opportunities these conditions presented.

The central aim of this study is to account for the Marashea’s ability to survive throughout the apartheid era. To this end, I explore the ways in which identity formation, gender relations, economic opportunism, collective violence, and political maneuvering contributed to the long-term integrity of the gangs. There were four pillars to the Marashea’s success: its economic relationship with mineworkers, its nonadversarial stance toward the apartheid state, the control of migrant women, and ethnic mobilization. The following summary of the history and historiography of urban violence provides a context within which these strategies and the Marashea gangs themselves can be better situated.

A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF CRIME, POLICING, AND VIOLENCE

We have a reasonably good understanding of the development of different criminal organizations and patterns of collective violence in twentieth-century South African townships. The discovery of massive gold deposits in the area that was to become Johannesburg attracted fortune seekers of European descent from all over the world. The corresponding demand for cheap labor brought Africans from throughout the subcontinent to work in the mines and associated industries. Between 1887 and 1899 Johannesburg was transformed from a mining camp with a population of three thousand into a metropolis with over one hundred thousand inhabitants.3 In a rough environment where criminals of all population groups plied their trades, successive white governments worked to bring white society under control. Legislation designed to eradicate organized criminal activity was introduced and hundreds of white gangsters were imprisoned and deported between 1898 and 1910.4 In contrast, the densely populated, impoverished, and ethnically diverse black settlements that had mushroomed on the fringes of mine properties and white neighborhoods enjoyed no such protection. As long as violent crime was contained within the townships and posed no threat to whites, it was not a police priority.

In the first half of the twentieth century, a succession of migrant gangs, most with close ties to the mining industry, dominated the criminal landscape.5 The Zulu-based Ninevites on the turn-of-the-century Witwatersrand terrorized the inhabitants of urban black locations.6 In early-twentieth-century Durban, attacks on unsuspecting individuals by gangs of migrant “kitchen boys” known as Amalaita “remained a ubiquitous feature of suburban labouring life.”7 The Rand mining compounds of the 1920s and 1930s were plagued by the Mpondo Isitshozi gangs, which “established a reign of terror on the paths leading to and from the mines.”8 A resident of Johannesburg’s Western Native Township, reflecting back on the early 1930s, recalled, “The most dreaded gang in those days were the [Pedi-dominated] Amalaitas. . . . They used to beat up people mercilessly.”9 After its emergence in the late 1940s the Marashea soon became the dominant migrant gang on the Rand.

Young thugs, known as tsotsis, formed street corner gangs in the 1940s and 1950s, following the waves of massive black immigration to urban centers that occurred during the Second World War. The tsotsi phenomenon took root as large sections of the rapidly growing population of urbanized youth turned to violent crime. Indeed, Clive Glaser claims that by the 1950s “the majority of permanently urbanized black youths in South Africa’s key urban conglomerate, the Witwatersrand, was involved, to a greater or lesser extent, in tsotsi gangs.”10 In Cape Town’s District Six, before the population removals of the 1960s and 1970s, extended family gangs “ordered the ghetto through their connections, intermarriages, agreements, ‘respect’ and ultimately, their force and access to violence.”11 Tsotsi gangs such as the Black Swines and the Pirates established a strong presence in Soweto in the 1960s, while the Hazels reigned supreme in the 1970s.12 And although it seems that many Soweto gangs were thrown on the defensive by politicized students following the 1976 uprising, they reemerged in the form of the “jackrollers” of the 1980s and 1990s. In the Cape Peninsula, the relocation of Coloured communities to the Cape Flats spawned several different types of criminal syndicates that have survived to the present day. Many gangsters and their gangs, like Rashied Staggie of the Hard Livings Gang, have become household names.13

The impact of policing designed to serve white needs can be traced to the early days of the Rand. The Ninevites dispensed their own rough brand of justice in Johannesburg because for Africans it was “a town without law.”14 John Brewer summarizes township policing in the 1950s: “Passes and documents were checked, raids for illicit liquor conducted and illegal squatters evicted, all while murder, rape and gangsterism flourished.”15 A 1955 report on youth crime on the Rand recorded that gang members boasted openly that police were so intent on liquor and pass offenses that tsotsis had little to fear from them.16 The police campaign against township youth during the 1976 Soweto uprising marked a turning point in community-police relations as increasing numbers of township residents turned against the SAP.17 With protest against the apartheid regime mounting throughout the 1980s, the police focused almost exclusively on political offenders. Hence, the Diepkloof Parents’ Association’s 1989 complaint: “There is a growing feeling in the community that the SAP is quick to act against anti-apartheid activists and their organisations but they do nothing to stop the criminals presently terrorising us.”18 During the final decade of apartheid, the SAP was deeply implicated in the violence that engulfed so many townships across the country.

Just as the absence of adequate policing and social control provided an incentive for township gangsters, the lack of state protection necessitated the formation of vigilante movements as communities organized to protect themselves and punish suspected offenders. Neighborhood policing initiatives known as Civilian Guards were formed in the 1930s on the Rand, and township residents consistently supported such movements for the next fifty years. ANC supporters established street committees and people’s courts in the 1980s and 1990s and vigilantism and popular courts continue to play a prominent role in many townships.

A HISTORIOGRAPHY OF VIOLENCE

Within the sizable South African literature dealing with violence, only the more recent episodes of civil conflict have inspired integrated analyses that investigate the manner in which various police forces, criminal gangs, vigilantes, political groups, and localized struggles interconnected to fuel the cycle of conflict.19 Despite widespread recognition that endemic violence is almost always the product of a combination of circumstances and forces, South African historical accounts tend to treat criminal gangs, vigilantism, and policing as separate phenomena. Furthermore, very few analyses explore township violence over a protracted period to identify trends and turning points.20 Thus, the historical literature focusing on urban crime and violence constitutes a collection of isolated case studies that are still largely mired in the resistance-collaboration framework.21

Tim Nuttal and John Wright recently observed that South African historians have long been “in one way or another, to a greater or lesser degree, caught up in the deep and narrow groove of ‘struggle history.’”22 Many leading South Africanists came of age in apartheid South Africa and identified with the struggle against racist oppression. Not only did this result in the categorization of a multitude of different acts and behavior as resistance, but groups that cooperated with the authorities or who came into conflict with liberation movements have typically been classified as collaborators. Attempts to provide more subtle and nuanced interpretations of the struggle still tend to view resistance as the definitive South African story. For example, in their call to expand the category of resistance, Bonner, Peter Delius, and Deborah Posel argue that “the resistance and opposition which confronted the governing authorities was far more wide ranging and amorphous than has been revealed by the conventional focus on national political organisations. Countless individual or small-scale acts of non-compliance proved more pervasive, elusive, persistent and difficult to control than more formal or organised political struggle.”23

Here we have the tendency to conflate survival with resistance and to imbue a wide range of prosaic activities with subversive dimensions. Frederick Cooper explains the allure of this approach: “Scholars have their reasons for taking an expansive view. Little actions can add up to something big: desertion from labor contracts, petty acts of defiance of white officials or their African subalterns, illegal enterprises in colonial cities, alternative religious communities—all these may subvert a regime that proclaimed both its power and its righteousness, raise the confidence of people in the idea that colonial power can be countered, and forge a general spirit conducive to mobilisation across a variety of social differences.” However, as Cooper points out, such a sweeping interpretation of resistance undermines an appreciation of the complexities of colonial societies and reduces the lives of the colonized to participants in the struggle against colonial oppression. As a result, “the texture of people’s lives is lost; and complex strategies of coping, of seizing niches within changing economies, of multi-sided engagement with forces inside and outside the community, are narrowed into a single framework.”24 Following Cooper’s lead, Africanist scholars have increasingly abandoned the basic oppressor-resistor axis in favor of a more multilayered understanding of the relationships that comprised the colonial process. Nancy Rose Hunt argues, “Social action in colonial and postcolonial Africa cannot be reduced to such polarities as metropole/colony or colonizer/colonized or to balanced narrative plots of imposition and response or hegemony and resistance.”25

Some historians of settler states, which suffered more oppressive forms of colonial rule and experienced bloodier trajectories to independence, have had a difficult time abandoning these polarities. Teresa Barnes claims that while local struggles and misunderstandings existed in colonial Zimbabwe, a larger struggle was operative. Most settlers acted like racist overlords and most Africans resisted colonial rule. She warns, “Lilting along in deconstructionist mode . . . can lead scholars to miss the forest for the trees.”26 However, one can accept that most white South Africans were racist and that most black South Africans were opposed to white rule in general and apartheid in particular without narrowly defining the lives of the colonized according to their relationships with the forces of apartheid, however such relationships were perceived.

Resistance needs to be distinguished from the strategies of avoidance, manipulation, circumvention, and adaptation regularly employed by black South Africans. Negotiation and navigation are more useful labels for these coping strategies. Most people living under colonial rule navigated the spaces available to them and created new spaces in which to realize their aspirations. The colonized were forced to deal with constraints imposed by oppressive regimes and usually chose to quietly subvert rather than openly challenge those conditions. Specifically because colonial states suppressed groups and individuals that posed a direct threat, navigation and negotiation were generally more prudent and popular options. They allowed colonial subjects more latitude to achieve their immediate objectives and the daily business of survival ensured that most people prioritized these immediate needs rather than focusing on resistance. Accepting these concepts as the most common strategies of engagement with colonial rule does not signify a belief in the essential passivity of black South Africans or any other colonial subjects. Instead, this approach recognizes that people coped with repressive conditions in an almost infinite variety of ways.

The study of criminal gangs has proved particularly susceptible to the resistance-collaboration dyad. Analysts have tended to depict black South African gangsters as social bandits battling the repressive state on behalf of the oppressed masses,27 or less commonly, as destructive predators victimizing fellow blacks and undermining progress.28 To privilege a gang’s relationship to the government and its agents as the defining characteristic of that gang (whether the gang is classified as antistate, apolitical, or allied with the government) overlooks the complex manner in which gangs fit into their communities and the variety of roles they played in the townships.29 This approach also obscures the issue of identity. Gang identities were forged as a result of numerous factors—relations with rival gangs, the methods by which gang members supported themselves, political affiliation, specific rituals and cultural idioms, gender relations, ethnicity, age, territorialism, and so on—designed to contextualize the world of the townships, an environment in which the white-ruled state was an important but by no means the only, or even the dominant, influence. Group identities, which shaped activities and community relations, developed to meet the needs and correspond with the worldviews of gang members struggling to survive in hostile surroundings. Gangs tended to be preoccupied with rival groups within the townships rather than with larger political issues. This is not to argue that gangs defined themselves exclusively through relationships with competitors or did not consciously resist the agents of the state, only that a host of influences contributed to gang identity and determined gang activities. In other words, it is unlikely that gangs defined themselves, or were regarded by different groups in the community, primarily according to their place on the resistance continuum.

Focusing exclusively on the destructive impact of gangs obscures the multifaceted roles these groups performed within the townships. Without discounting the mayhem gangs inflicted on urban residents, it is important to recognize that the communities that harbored criminal groups did not view them solely as a destructive force. It is unlikely that gangs could have flourished in South Africa without a significant degree of support from segments of urban communities. This support shifted in emphasis, from mere tolerance to outright alliances, and different gangs drew support from different sections of the community at different times, contingent on a variety of social, economic, and political factors.

Gang-community relationships merit much closer scrutiny than they have typically received. Resentment toward the authorities that regulated township dwellers’ movements, rights of residence, and access to jobs and subjected townspeople to constant harassment through liquor and pass raids meant that gang violence directed at the police was likely to be celebrated by many community members. A former tsotsi highlights the ambivalent relationship between gangs and their neighbors. “The gangs were a great paradox. People couldn’t understand why they would rob them, stab them and then fight the police. So there was this love-hate relationship.”30 Other than battling the police, gangs engaged in activities that met with varying degrees of popular approval, including the victimization of white-, Indian-, and Chinese-owned businesses, brawls with white gangs, and participation in political initiatives. Moreover, many gangs conducted their criminal activities away from their home areas and thus probably did not earn the enmity of the people among whom they lived.

Some township residents shared in the spoils of the gangs’ criminal exploits, especially through the distribution of heavily discounted stolen goods.31 Poverty and the brutally high rates of unemployment in the townships ensured that many families appreciated any source of income, including proceeds from criminal activity, and in certain areas gangs provided crucial economic inputs. Cape Flats gangs seem particularly influential in this regard: “They are popular figures providing income for an estimated 100,000 people through the illicit economy they control, sometimes paying the water and electricity bills of entire neighbourhoods.”32 Such developments fostered an economic interdependence between gangs and local residents and entrenched an acceptance of criminal culture within large sections of the affected communities. Although the vast majority of gangs were predatory in some respect, they often engaged in activities or represented ideals that were approved by substantial numbers of township residents.

THE MARASHEA

Readers familiar with South African urban and gang literature will have come across the Russians in articles by Bonner, Jeff Guy, and Motlatsi Thabane and, more recently, some of my own work.33 Despite the gangs’ widespread reputation for violence and the fact that the association has operated in South Africa for more than fifty years, these articles are the sole publications whose primary focus is the Marashea.34 Bonner, much like Guy and Thabane, presents the Marashea as a fighting association of Basotho migrants who banded together on the Rand in the 1940s and 1950s for protection from urban criminals and ethnic rivals, to obtain control over migrant Basotho women, and to celebrate their identity as Basotho by engaging in exhilarating internecine battles. Both articles deal with the Russian gangs in their formative years on the Rand and pay special attention to the violence that seems to have defined the gangs. Indeed, Bonner states, “The Russians on the Reef were, above all, a fighting machine.”35 Neither study extends its focus beyond the Witwatersrand of the 1950s, although Bonner claims that increasingly heavier prison sentences imposed on regular offenders, combined with more stringent influx controls, significantly weakened the Russians by the mid-1960s.36

While the Russians retained a presence in Johannesburg and neighboring towns, the strength of the association shifted to informal settlements and townships surrounding the newly established gold mines. Members not employed on the mines were forced to seek alternative sources of income, and the gangs became increasingly commercially oriented. In particular, they established large-scale liquor distribution and prostitution rackets that catered to the needs of African mineworkers housed in single-sex hostels. The patronage of mineworkers became the economic backbone of the Marashea, and different gangs operated throughout the mining areas. Their close ties with miners ensured that the groups became involved in the often violent politics of the mining industry. As mining groups expanded, the remaining urban Marashea struggled to survive. With diminishing numbers and a shrinking economic base, these groups competed fiercely for resources and became central players in a series of taxi wars that raged throughout the 1980s. However, despite efforts to maintain connections with their colleagues in the mining areas, the Johannesburg gangs were never able to regain their former stature.

The politicized conflicts of the 1980s and 1990s drew in the Marashea, along with many other combatants. A number of mining groups fought with supporters of the newly formed National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), which had close, albeit informal, links with the ANC. Marashea networks of influence and patronage were threatened by this new force, and the gangs defended their interests, sometimes in collusion with mine management and security. Following bloody and protracted fighting, the NUM emerged victorious and the Marashea had to adapt to a new political dispensation on the mines. The Russians were not as active in the violence on the Rand, which was dominated by conflicts between ANC supporters and IFP-aligned hostel dwellers. The few incidents of conflict seem to have been fought largely along generational lines when older members of the urban Marashea groups refused to recognize the authority of the youthful comrades. These disputes, while bloody, were overshadowed by ANC-Inkatha hostilities. The Marashea continues to operate in South Africa, although its livelihood is threatened by retrenchments in the mining sector and the AIDS pandemic that is taking a particularly heavy toll among mining populations.