Читать книгу Ring of Bright Water - Gavin Maxwell - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

‘THAT WAS Camusfeàrna down there,’ said my hiking companion. We were on the high backbone of Sleat, the southern peninsula of the Isle of Skye, looking down across the Sound of Sleat to a group of small islands and a little bay on the mainland shore of Scotland’s west coast directly opposite.

I could see what appeared to be a miniature lighthouse on one of the islands and a low white house set back from the beach at the bottom of a steep coastal drop with a high mountain rising straight up behind it.

It was a shock of recognition, for unexpectedly I had come across the famous setting of Gavin Maxwell’s Ring of Bright Water, and what had been for me, up to that moment, a literary landscape whose real location was unknown suddenly revealed itself before my eyes as an actual, physical landscape. Then I realized that we were standing on the very ground from which Maxwell used to hear the stags roaring in the early autumn – ‘I hear them first on the steep slopes of Skye across the Sound, a wild haunting primordial sound that belongs so utterly to the north…’

As if reading what might be in my mind my companion said, ‘That croft you see is not the house – the house burned down.’ Unexpected, too, this information about the later history of the place; I had read only Ring of Bright Water, and knew nothing beyond it.

It was a marvelous bright day with tremendous scenery, and under the cloudless blue vault of sky, a calm shimmering sea below stretched out on the right to that vanishing point where the sea and the sky meet. We saw eagles and ptarmigan, and a single one-antlered stag, almost berserk with joy at finding himself alone with forty hinds, raced about thrusting his one antler at every female within reach. But it was the glimpse of Camusfeàrna that remained my most vivid recollection.

Three years later in different company on a Highland moor, I chanced to mention something about the life of Gavin Maxwell, and one of the company said, ‘Yes, there was the curse of the rowan tree, the house burned down, and the fire killed the otters.’ More enigmatic pieces of information – I still had read only Ring of Bright Water – but strangely I did not seek further enlightenment, again only letting this sit somewhere in my mind.

Not long after that I happened upon the two sequel books about Camusfeàrna, neither of which I had known existed, in a couple of second-hand bookstores, and I found them in the order of their publication – first The Rocks Remain, then Raven Seek Thy Brother. So I finally learned, through Maxwell’s own writings, about the remaining story right up to its end.

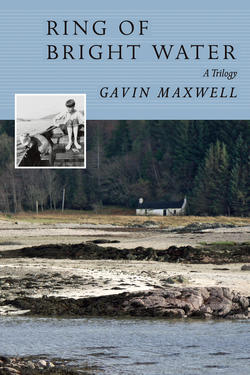

This is the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Ring of Bright Water, the first book of the present trilogy, which has achieved great and widespread fame as a modern classic in its time, and still retains some of that to the present day. Its overwhelming reception in the early 1960s, producing a readership of well over a million people on both sides of the Atlantic, may owe something to the culture of that particular time which seized upon the compelling presentation of an attainable Eden in the world of the here and now.

Today’s readers might well respond even more strongly to this story as an antidote to the dominance of a technological culture, and the broad detachment of humanity from the natural world. When Gavin wrote in 1959, ‘I am convinced that Man has suffered in his separation from the soil and from the other living creatures of the world,’ he could not have imagined how extreme this separation would be in the early twenty-first century. The pervasive impersonal, electronic world that frames our personal, intellectual and social lives, along with an associated materialism, makes Camusfeàrna an even more compelling ideal than it was half a century ago.

Maxwell’s notion of living in a paradise of nature in such a place has a precursor far back in time; the isolated location of Camusfeàrna on the edge of the sea, surrounded by rocks, trees and mountains, in a life of close proximity to wildlife hearkens back to an older tradition in the very same landscape. In the ninth and tenth centuries Celtic hermit monks lived in solitary dwellings on the coasts of Scotland and Ireland, especially on those coastal slopes, like Camusfeàrna, facing south and west, and they wrote Gaelic nature poetry of a very high order. Often they also described the wild creatures they lived near and wrote about as beloved friends.

Camusfeàrna

Camusfeàrna was a real place, but even more it was a world of the imagination. It failed spectacularly as a reality, but it will last forever as an imagined creation. The passages of rich scenic description in the early pages of Ring of Bright Water could hardly be bettered, but one sentence later in the book seems to capture the idyllic dream completely, ‘That summer at Camusfeàrna seemed to go on and on through timeless hours of sunshine and stillness and the dapple of changing cloud shadow upon the shoulder of the hills.’ The tiny world of the actual place has been expanded by art to become a timeless and all-encompassing universe, and it offers the promise of happiness of a golden age. This is what still brings pilgrims to place sea shells on the boulder marking Gavin’s grave, much like those other readers and pilgrims who place stones on the cairn marking the site of Thoreau’s house at Walden Pond.

Perhaps the element in this narrative that is most fascinating and gives the story its fame, is Gavin’s intense engagement with the three foreign otters (one from Iraq and two from West Africa) against the backdrop of the natural landscape with its waterfall, encircling ‘ring of bright water’, sea coast and lonely house. They were not native wildlife, but alien, controlled, exotic fauna that introduced a new personality into the Scottish landscape. Gavin slept with them in the house, played with them in the sea, exchanged saliva with them, and in some sense tragically mismanaged them.

Maxwell once described Ring of Bright Water, as ‘no more than a kind of personal diary’, much as Thoreau pretended that Walden was just the chronicle of one year’s life in the woods – ‘and the second year was similar to it.’ But both are carefully designed narratives that in some ways may be called fiction: the actual events and observations may be true, but so selected, arranged, and concentrated through literary art that the narrative becomes a kind of fiction and has the kind of intensity that only fiction possesses.

The present work contains the three books about Gavin Maxwell’s life at Camusfeàrna from 1948 to 1968; he first took possession of the house in the autumn of 1948, and he kept up that residence until January 1968. This trilogy presents in edited form the entire story by Maxwell, in a single, unbroken narrative, of his tenure at the place he called ‘Camusfeàrna’, a fictional name he gave to a real place in order to emphasize its symbolic topography.

Ring of Bright Water, which Maxwell finished writing in October 1959, chronicles roughly the first ten years of his life there, describing the simple, idyllic paradise that has enchanted readers throughout the world. The Rocks Remain (1963) and Raven Seek Thy Brother (1968), very different books from their predecessor, recount the last decade.

It has been possible to combine these three books into one volume largely due to the content of the two later books both of which contain much narrative material extraneous to the story of Maxwell’s Scottish home. Some of this writing set in Morocco, Majorca, Iceland, etc. is wonderful, but has no place in our story, and it is distracting to the tale set in Scotland.

Although the first book, Ring of Bright Water, is Maxwell’s masterpiece, the book everybody knows, it plays a different and almost subordinate role here, only the first section of a more extensive, personal, dramatic and entirely different story. It is the first chapter, point of reference, and partly the cause of the failure of the single vision of simplicity and harmony told within its pages. Again and again in the dark portions of The Rocks Remain and Raven Seek Thy Brother, Maxwell compares the before and after: with the changes brought about by the prosperity that came with the first book’s huge success a manifest decline began in almost every happiness that Camusfeàrna had represented.

First, the telephone and electricity, an intrusion of the outside world into the paradise that was ‘almost an island’; an attempt to keep two African otters at the same time (they turned out to be ferociously hostile to each other), requiring extensive and ugly building construction and a salaried keeper for each animal; boat accidents, accidents in and out of the house, a dangerous breakdown in the relationships with both otters; vast expenses, growing swings of fortune and misfortune; anxiety about the management of an increasingly complicated life; mistakes and misjudgments, serious illnesses; all of this recounted by Maxwell as a downward spiral of his existence.

But in spite of the litany of disasters and the unrelenting march of calamitous adversity over a period of years, a moving redemption comes towards the end with a restoration of love and trust in the relationship with the otters, and a momentary restoration of the feeling of the old life there.

Gavin Maxwell’s legacy may well include his undoubted influence in shaping public opinion to put an end to the tradition and practice of otter hunting, a cruel sport with no purpose to it. Douglas Botting, Maxwell’s biographer, has said, ‘Gavin made his greatest impact through Ring of Bright Water, which marked the beginning of a groundswell of support for otter conservation that has continued to the present day. Gavin’s contribution to saving the otters was immeasurable.’

But his greatest legacy has to be the creation of that place he called Camusfeàrna, an imperishable small spot on the map of Scotland, ‘sky, shore, and silver sea,’ where the imagination can go in a dream and which he marked down on the world map of literature.

AUSTIN CHINN