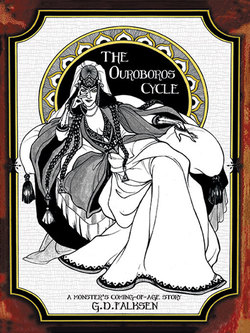

Читать книгу The Ouroboros Cycle, Book One - G.D. Falksen - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

There is much that is uncertain, but this much is true: the beasts that from time to time plague our lands are not an isolated occurrence. In my travels I have seen shrines and icons and statues of these monsters, creatures not quite man nor wolf nor bear but an unholy mixture of the three. I have found sacrificial pits dedicated to them beneath the forgotten cities of Sumeria. I have seen statues and masks of these same creatures in the lands beyond Abyssinia. I have walked through temples dedicated to their likenesses lost in the forests far to the south of Kanem and Mali, in the mountains of Bactria, and in the great deserts of Tartary. In the lands of the Franks there are caves in sacred groves decorated with paintings of these beasts. In Greece, Palestine, and Egypt I have found no less than seven monasteries adorned with these icons, and many others that refused my entry to examine the rumors about them. And to my horror, I learned upon my journey that the worship of these creatures is not a practice that has been forgotten by time.

In the great cities of the world, in Constantinople, Jerusalem, Baghdad, and Rome, I have found cults that to this day give men, women, and children as offerings to their beast-gods. They congregate in the deep places beneath these cities where their foul acts go unnoticed, but they count among their number many of the great lords of the civilized world. There are stories of unnatural congress between the beasts and their followers, of men who are born in God’s image but with age transform into the unholy. I have heard similar stories in other places: tales of the Norse berserkers who become as bears, and of the Turks who claim lineage from the wolf Asena. Let us remember that Rome was founded by Romulus and Remus who were nursed by a she-wolf, and that the Bible tells us of Benjamin, who is as a ravening wolf. Such tales would not haunt me so were it not for what I have seen.

In Paris, I met a cultist who I persuaded to tell me of his beliefs. Among other things I asked him how the cult of these creatures could exist in so many disparate places and among so many peoples. He called the creatures “Scions”, though he pronounced it as if it were “Skion”; perhaps a derivation of an older word from another tongue. He used this analogy to illustrate the point thusly: A man walks through a forest and encounters a tree hidden behind a mass of bushes, each different from the next. Only the twigs of the tree’s branches may be seen, but these all bear beautiful flowers that are clearly of a similar nature. The man does not understand how so many flowers can be so alike growing, he thinks, from different bushes. He does not see that they all spring from the same tree. These Scions, said the cultist, are all descended from the lineage of a great wolf-god older even than the God of Abraham. The truly faithful are blessed by allowing unnatural congress with these beasts, creating offspring that are born as men but in time become as wolves. This much I knew, or perhaps hoped, could not be true, but I dread to think how many of the world’s great kings and nobles come from families that have sought to mix their blood with these creatures.

I slew the cultist of course, and his congregation. My conscience would not allow otherwise. I am left now to wonder how old and how widespread this cult can be, and just how much of its blasphemous doctrine may be true. What can these Children of the Wolf intend for mankind? Do they mean to one day feed us all to their ravenous gods?

—Konstantine Shashavani,

excerpt from On The Nature of Beasts and Men

(unfinished, c. 1300)