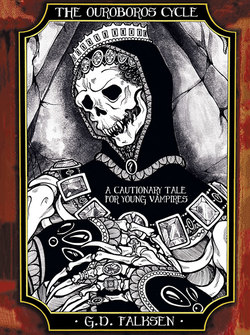

Читать книгу The Ouroboros Cycle, Book Two: A Cautionary Tale for Young Vampires - G.D. Falksen - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Six

Blackmoor, England

A week later, Varanus stood on the railway platform at Blackmoor in the midst of a vast expanse of moorland, a sea of black and red and dull yellow broken only by a scattering of small homesteads and peaks of dark rock that jutted from the ground like clawing fingers. The land was low but rolling, with hills topped by granite tors. There were streams that trickled through the grass, pooling into bogs when they could not find a course to the sea.

Dusk was falling. The fading sunlight covered the rolling moor in bitter orange. A few flocks of sheep were seen hurrying this way and that in the grass, but otherwise little stirred. It was as if all life had fled the approach of darkness. Even the birds were silent.

“This may be the most desolate place I have ever seen,” Varanus said softly.

She lifted her veil to see better. With night coming and the sun behind them, she no longer had need of it. But for good measure, she still wore a pair of dark glasses to shield her sensitive eyes.

At her side, Ekaterine said, “It reminds me of Scotland.”

“I didn’t know you’d been there,” Varanus said.

“I haven’t,” Ekaterine replied. “Luka went once, with Lord Iosef. He brought back a painting for me. It looked very much like this, only with mountains.”

The scene did indeed lack mountains, Varanus thought, but not for lack of trying. Each stone-topped hill seemed to reach upward as if inspired yet unable to become a towering peak. Indeed, the very land dropped away as if intending to further this aim. The train station sat on raised ground, but within only a few feet the ground began to slope away into the Blackmoor plain.

“I must say, this is not what I had anticipated,” Varanus said. “What has become of England’s green and pleasant land?”

It was certainly nothing like the remainder of Yorkshire, which they had seen along their journey. That land had been lush and beautiful. Varanus looked southward, the way they had come, and could just make out the hint of a familiar, vibrant green beneath the horizon. Turning back toward Blackmoor, she was faced again with burnt umber and desolation.

“Ought we to walk to town?” Ekaterine asked.

“The baggage will be something of a chore,” Varanus replied. She nodded to the two trunks they had brought with them. “And my cousin did assure me that we would be met at the platform.”

“Considering that there is little of the station but the platform, that would seem necessary,” Ekaterine said. She looked this way and that, her mouth set tightly in irritation. “This is not an auspicious beginning, I must say.”

But Varanus had spied something dark moving along the road to town. Even at that distance, she could make out the shapes of horses pulling a carriage of some sort.

“No fear,” she said. “They are late but approaching.”

“And I thought that the English were punctual,” Ekaterine said.

They waited in silence as their transportation approached. In due course, a weathered black brougham pulled up to the platform. Its driver was a gangly fellow with matted black hair and side-whiskers. He wore a tall hat, a weathered suit with trousers tucked into tall boots, and a heavy overcoat with shoulder capes, all as black as his carriage, his horses, and his whiskers.

“What a sinister display,” Ekaterine murmured. She grinned. “It’s rather exciting isn’t it?”

“Oh, hush,” Varanus said.

The coachman leaned down and touched the brim of his hat with his fingertips.

“Pardon fer me lateness, Yer Graces,” he said. “I were delayed in town.”

Varanus smelled whiskey on his breath. Delayed in town? Delayed in the pub, more likely.

“Well, you are here now,” she said.

“Which’a ya is the Princess Shashy’vany?” the coachman asked, climbing down from his seat.

“Shashavani,” Varanus corrected him, emphasizing each part of the name. “And I am she.” She motioned to Ekaterine. “This is my sister-in-law. You may also address her as Lady Shashavani.”

“Yes, Yer Grace,” the coachman said, bowing his head. “Me name is Barnabas, should me services be required durin’ yer stay. I’s coachman to th’ Earl o’ Blackmoor.”

“Of course,” Varanus said.

Barnabas bowed his head again and opened the door of the brougham. Varanus politely accepted his assistance in climbing inside, as did Ekaterine. There was no need for their self-reliance to offend the help. The seat inside was old and worn, but still soft enough to offer some degree of comfort. At least it was better than the coachman’s box outside. And warmer as well, Varanus wagered. Though it was only September, there was a chill in the air.

The coachman heaved their luggage onto the roof of the brougham and climbed into his seat.

“Not a long journey, Yer Graces,” he called down to them. “An’ ya can see the countryside along the way.”

* * * *

There was little to the countryside that Varanus had not already seen, but up close it proved somewhat more interesting than at a distance. The brougham drove first through the Village of Blackmoor, an ancient and weathered relic of an earlier age. A great many of the buildings were stone or brick, and much of the construction seemed to date back to the Eighteenth Century or earlier.

Though many of the winding streets they passed were deserted, the main road through town had more than its fair share of people. Whether they had come to see the arrival of strangers or were simply on their way to the local pub, Varanus could not say. But regardless, they all backed way from the approaching carriage as quickly as possible and clustered along the sides of the street to watch. Their faces were as tired and worn as the buildings of the village. Their expressions spoke of apprehension and fear.

“I don’t think we are welcome here,” Varanus said.

“Perhaps,” Ekaterine said. “But they have no idea who we are. The coach, however, they must recognize.”

They were soon free of the village, and Varanus watched the barren landscape roll past them as the brougham followed the main road toward Blackmoor Manor. As she had surmised before, there was very little on the moor aside from a few cottages and the odd church. Here and there she saw a standing stone or an isolated monument that had been placed in the wilderness for no evident purpose. But otherwise, there was nothing to be seen but the grass and the heath and the tor-topped hills.

Blackmoor Manor sat atop a hill a little over a mile outside of the village, as much a weathered relic as any of the buildings in town. A three-story Tudor construction, the house was built in the manner of a fortress, with parapets and towers set alongside grand arches and windows. There was even a gatehouse that led into a central court, inherited from an earlier, far more violent time. The stonework was worn smooth by rain and wind and stained so that it was almost black.

Blackmoor indeed, Varanus thought. The ground, the rock, even the manor.

The coachman drove them into the central courtyard. There were lanterns hanging over both the gate and the door to the house, and two rows of torches led the way from one to the other. Bathed in the orange glow of fire and sunset, the dark walls looked rather like vertical faces of bare rock, and in the gathering shadows, the courtyard put Varanus in mind of some place of pagan sacrifice.

What a dreadful thing to think about the home of one’s ancestors, she thought.

A man was waiting for them on the steps when they alighted, with a party of servants standing behind him at the door. The man was tall and broad-shouldered, though he looked slim and elegant in his dark gray frock coat—a marvel of tailoring to be sure. He was handsome, with a sturdy jaw, a large but narrow nose, and high cheeks and brow. At the sight of Varanus, his mouth opened in a wide smile that showed his strong, ivory-colored teeth. His hair was black but graying, rich and full, and longer than was common among most men of his age.

Varanus recognized him from when he had visited her a year ago to pay his condolences. He was her Right Honourable cousin Robert, the Earl of Blackmoor. But, she wondered, was he to be her friend or her adversary? That remained to be seen. The family had made clear their claim on her grandfather’s property, but she still held a hope that the ties of blood would win out over the power of greed.

Robert advanced down the steps, still smiling. A pair of sizable hounds—at least three feet at the shoulder—followed at his heels, their eyes firmly fixed on Varanus and Ekaterine. They kept sniffing the air and looking at their master, perhaps wondering if the newcomers were friend or food.

“Cousin Babette,” Robert said warmly, taking Varanus’s tiny hand in both of his. “I am so pleased to see you. And doubly pleased that you are out of mourning.”

“Indeed,” Varanus said, “it is wonderful to see you as well, Cousin Robert.”

Varanus was not entirely clear on protocol, but if he was going to avoid calling her Princess Shashavani, she would be damned if she would call him Earl Blackmoor.

“Allow me to introduce my sister-in-law, Princess Ekaterine Shashavani,” she continued, motioning to Ekaterine.

“A pleasure to meet you,” Robert said, bowing his head ever so slightly.

“And you,” Ekaterine answered, smiling.

“Shall I call you cousin?” Robert asked, his voice betraying the teasing tone of a man who knew that he was the master, regardless of the rank of his subjects.

“Oh, I should like that very much,” Ekaterine said, evading the provocation. “I already feel part of the family.”

Robert’s smile never wavered. Without a word, he snapped his fingers twice. The hounds whined softly and scurried off to their kennels at the side of the courtyard.

“Allow me to introduce the staff,” Robert said. He extended his arm and indicated each in turn.

“Harris, the butler.”

A broad-shouldered man of advancing years, cleanly shaven and slightly balding. His bearing was sturdy and dignified, and his person was well maintained, though his tie was crooked and his cuffs were slightly dirty. Still, he surely knew his business if Cousin Robert kept him despite a degree of disorder.

“My housekeeper, Mrs Wilkie.”

Tallish, narrow, sharp in the face. And sharp in the eyes. Varanus saw cunning and determination there, before Mrs Wilkie obediently looked down.

“The footman, Peter.”

A young lad, very energetic, but polite and exceedingly servile. Varanus could almost smell the obedience on him. A good quality in a servant, no doubt, but still.…

“The head housemaid, Gladys, and the chambermaid, Lucy.”

Pleasant girls, very pretty. Fair-haired. Almost identical. Quite possibly sisters. It was a point worth noting, whatever it entailed.

“And in addition,” Robert continued, “as your own maids are not with you, my wife and my eldest daughter’s lady’s maids shall be attending to you in that capacity. Miss Hudson for Cousin Babette and Miss Finch for Cousin Ekaterine.”

It would be a bother having maids intrude upon her privacy, but Varanus could expect nothing else. This was the wider world, where the servants would not understand her wish to attend to herself unaided. It was not like being at home among the Shashavani. She and Ekaterine had assisted one another for so long that servants were not necessary. And she had not become accustomed to the ones she had hired to dote over them in London. At least Cousin Robert did not take offense at their arriving without maids; indeed, he had all but suggested that they come unattended in the letter. Varanus suspected it was a plot to isolate her from anything familiar when the time came for negotiations.

“And you have already met Barnabas,” Robert finished. “Should you require transportation during your stay—into town perhaps, or to see the sights on the moor—he will be at your service.”

“Splendid,” Varanus said. “I am beginning to feel at home already.”

“It is the ancestral home of the Varanuses,” Robert said, his smile a little too wide. “Now come inside and meet the family.”

* * * *

Robert led Varanus and Ekaterine into the front hall, a spacious two-story chamber floored and paneled in ebony and adorned with portraits and landscape paintings. Above the doorway Varanus saw a pair of swords crossed beneath a shield bearing the arms of the Blackmoors: two wolves rampant in sable upon a gules field beneath an argent star. There were suits of armor standing in rows along the walls like men-at-arms ready for duty. Upstairs galleries overlooked the entryway on all four sides, and it did not escape Varanus’s attention that anterooms opened out into the hall to both left and right. In older, less civilized times real men-at-arms had probably waited there, ready to repulse any enemy who managed to breach the door.

Beyond the front hall stood a grand chamber with a high arched ceiling. Private balconies and a minstrel’s gallery overlooked the room from the second floor, and at the highest level a series of broad windows let in the last rays of the dying sunlight. Great chandeliers suspended from the ceiling on iron chains and tiered candelabra standing near the walls gave the chamber plenty of light. There were shields on the walls, banners signifying glories past draped along the side, and a grand dais at the far end of the room that suggested this had once been the great hall of a medieval castle.

All that was in the past of course. Now the harsh stone of the walls and floor had been softened by wooden floorboards, by curtains and tapestries, by carpets, sofas, and upholstered chairs. What once must have been the seat of the Blackmoor county had been transformed into a polite family parlor.

A company of people were waiting for them when they arrived—four women, one man, and a boy just on the verge of his teens. They were seated, pleasantly engaged in conversation, but they quickly stood and smiled in greeting as Varanus entered the room. They were all dressed conservatively, with long sleeves and high collars, somber colors, and precious little lace or accoutrements—save for the youngest woman, who wore pastels. It was what Varanus would have expected for country aristocracy so far removed from civilization. But the clothes were deceptive. After a moment, Varanus’s keen eyes caught sight of fine details and intricate lines. The eldest of the group—a woman of about fifty—wore what appeared to be a plain gray dress that matched perfectly the shade and style of Robert’s suit. But as Varanus approached, she saw that the dress was decked in lines of narrow braid and covered in tiny beads. Such delicate work, and all for the purpose of looking invisible?

“And at long last, our French cousin has returned,” Robert said. “Everyone, I am pleased to introduce Lady Babette Shashavani, the granddaughter of my dear great uncle, William Varanus, rest his soul. And with her is her sister-in-law, Lady Ekaterine Shashavani. This is a great honor for all of us,” he added, speaking in part to Varanus, “but they have kindly invited us to call them Cousin Babette and Cousin Ekaterine.”

Varanus’s eyebrow twitched. Again, Robert had endeavored to avoid stating her specific title—one dramatically above his—and he had given the family leave to address her in familiar terms without first asking her permission. Was it simple rustic exuberance or a deliberate effort to undermine her position?

The oldest woman clasped her hands together and smiled in delight. “That is splendid,” she said. “And you are most welcome here Cousin Babette. We are delighted to have you at long last in our home.”

“Cousin Babette, allow me to introduce my dear wife Maud,” Robert said, motioning to her.

Babette smiled and nodded. Maud’s poise and smile were flawless and remarkably sincere. In Varanus’s experience, the least sincere of people gave the most sincere smiles. But no matter. Perhaps she was being paranoid. The bleakness of the moor was enough to put anyone on edge.

“A pleasure, Cousin Maud,” Ekaterine said, matching her smile.

“Yes, delightful,” Varanus agreed.

Robert motioned to the next woman, a lady of about thirty with the rich black hair of Robert and the practiced poise of Maud.

“Our eldest daughter, Elizabeth,” he said, “and our youngest, Mary.”

Mary looked to be in her late teens, just the right age to be married. She was blond like her mother, rosy-cheeked, and painfully pretty in a dress of blue and pink—the only bit of color among the somber group. She bowed her head with a little bob and smiled sweetly.

“Sadly, our middle daughter, Catherine, now resides with her husband in America,” Robert said. “I have no doubt that she will be sad to have missed meeting you.”

“Of course,” Varanus said.

“And of course my son and heir, Richard,” Robert said, “his wife Anne, and their dear boy Stephen. They have just returned from India, and it is most fortunate that they are here to meet you.”

Varanus gave father, mother, and child a quick appraisal. Richard was rather like a younger copy of his father: dark, flowing hair, a strong jaw, broad shoulders, and an air of confidence bordering on arrogance. The boy Stephen, who looked to be around twelve, was much the same. He grinned at Varanus, rather than smiling, in a manner that was not at all polite. And then there was Anne. Varanus saw at a glance all that she needed to see: the slightly hunched shoulders, the downcast eyes, the timidity in expression, manner, and voice. The way that she seemed both to fear her husband and to fear being too far away from him.…

Varanus forced herself to smile. A husband’s tyranny was nothing new. It would do no good to comment upon it at such a time. Once her business was concluded, it would be a different matter.

“A pleasure to meet you, I’m sure,” she said.

“Alas,” said Maud, “our other son, Edward, is off on safari, God knows where. And he shall not return until he is finished.”

“I always find it’s good for a young man to get out into the wild before he accepts the mantle of adult responsibility,” Robert said. “Do some hunting, you know.”

“It is a shame that he is not here,” Maud continued. “I just know that he would have been delighted to meet you. Both of you,” she added, speaking in Ekaterine’s direction with sufficient emphasis to make Ekaterine and Varanus exchange looks.

Just as well he wasn’t there, Varanus thought. It was bad enough having her son chase after Ekaterine. Having two family members doing so would be the end of her patience.

“Well,” Robert said, “I expect you are tired from your journey. If you would kindly follow me, I will show you to your rooms. The servants will bring your luggage up presently. We have already dined, of course, but I have instructed our cook to prepare something hot for you to eat at your leisure.”

“That sounds wonderful,” Varanus said. “We are very grateful.”

“Perhaps after you have refreshed yourselves, you would permit me to give you a tour of the house,” Robert said. “I cannot imagine a Varanus having grown up without ever once visiting it. There is so much history in these walls, Cousin Babette. Your history. The history of your blood.”

* * * *

There was more than a little truth in what Robert had said. As Varanus followed him from room to room, through richly furnished parlors and elegant drawing rooms, she truly felt like she had returned home. Not her only home—both Grandfather’s estate in Normandy and the Shashavani valley in Georgia were immutably home as well—but walking through the house that had raised countless generations of her ancestors made complete some part of her that she had not known was missing. It was a strange experience, like having something added to an already filled glass.

Only Varanus had come for the tour. Ekaterine had elected to return to the great hall to observe the family in its natural habitat. Varanus was secretly grateful, for by the evening’s end Ekaterine would have a whole catalogue of useful information obtained through idle chitchat. The temporary reprieve was a relief to Varanus, who dreaded what time she would be forced to spend conversing in the company of her cousins.

“This is our humble library,” Robert said, as he led her into the room and turned up the gas lamps.

The blossoming light revealed the ubiquitous dark wood paneling that adorned the house, lush Persian carpets in burgundy and gold, and tall shelves filled with books and tomes and even the odd vellum codex dating prior to the invention of printing. It was a marvelous collection, rivaling the one at Grandfather’s estate. Of course, it could not compare to the library of the Shashavani, but it was still incredible.

“I fear, Cousin Robert,” Varanus said, “that ‘humble’ may be the wrong word for it. I do believe you meant to say ‘impressive.’”

Robert laughed loudly and replied, “Well, we are rather proud of it, yes. For hundreds of years, Varanuses have learned and studied in this room, and in the castle chamber that preceded it. Even after Varanuses began attending school, this was where all their real education took place. We have always employed the finest tutors, as we still do now to educate young Stephen. Though,” Robert added, sighing wistfully, “he shall be departing for Eton next year. I do wonder if we shall retain the services of the tutor or dispense with him.”

“How old is this collection?” Varanus asked, studying some of books nearest her.

“More than eight hundred years,” Robert answered. “It was begun with three illuminated manuscripts, brought from France by our ancestor Henry I during the Norman Conquest.”

“He was the first Varanus?”

Robert laughed and said, “No, no, we weren’t Varanuses then. And of course, Henry didn’t begin as a Blackmoor.” He paused and looked at her very seriously. “Do you know the history of our family?”

“Bits and pieces,” Varanus said. “My grandfather spoke of some things, but never our origins. Not in detail. I know that we came from Normandy and settled…well, here. But little beyond that.”

“That must be attended to,” Robert said, smiling in his toothy way. “Come, follow me to the gallery upstairs, and I will show you your ancestors face-to-face.”

Varanus followed him up a flight of steps just outside the library. They entered into a long gallery that ran what seemed to be almost the entire frontage of the house, save for the towers at either corner. Tall, narrow windows ran along the exterior wall, and on both sides were countless portraits of men and women, all of whom shared the strong features and sharp eyes of the Varanuses.

Robert stopped about midway along the gallery, where the interior wall opened into the balcony that overlooked the front hallway. On the opposite wall stood a collection of paintings, slightly larger than the rest and all greatly ornamented. At the center, largest of all, was a portrait in baroque style depicting a man clad all in mail, standing beneath the silver moon with two great hounds at his feet, hands resting upon the hilt of his sword. The man in the portrait was tall and broad. His hair was dark, curled, and cut to just below the ear. His beard was full but trimmed. His expression dominant.

“Our progenitor,” Robert said. “Henry of Rouen; later Henry, First Earl of Blackmoor.”

“A striking man,” Varanus said. “I can see the family resemblance.”

Robert laughed.

“Most Varanuses have certain traits in common,” he said. “Most.” Before Varanus could respond, he continued, “Henry was one of the companions of William the Conqueror during the Norman Conquest in 1066 and, according to legend, fought with all the bravery and ferocity that his descendants have become known for. He remained at court until the winter of 1069, when the nobles in the North of England rebelled against the new king. King William sent an army to put down the insurrection, and Henry of Rouen marched with it. What followed is called the Harrying of the North. Villages were slaughtered, crops destroyed, the whole land devastated.”

Robert looked toward the painting as he continued, his tone almost poignant, “By all accounts, Henry was among the most brutal perpetrators of the Harrying, yet by his orders a small number of select families and villages were left all but untouched by the retribution. To this day, it is not known why he chose them to be spared, but the King gave no complaint. And when it was done, it is said that Henry was offered the Earldom of Northumbria, but he refused it. Instead, he requested only a small, barren piece of land that he had spared from the horrors of the Harrying.”

“Blackmoor,” Varanus said.

“Just so,” Robert answered. “And so it was. Henry was made Earl of Blackmoor. He retired to this land, built a castle on this very site, married the eldest daughter of the Danish family that had formerly ruled here, and set about creating our family line.”

“How very charitable of him,” Varanus said. “And very forward-thinking.”

“I am certainly pleased by having ancestry,” Robert mused.

After a moment he chuckled and motioned to one of the adjacent paintings, which depicted a man not unlike Henry, dressed in mail and wearing the cross-emblazoned tabard of a crusader, who stood before the walls of Jerusalem with his sword upraised.

“This,” he said, “is Roger Varanus, the first in our line to bear that name. It is through him that we trace our patrilineal descent. Roger was the youngest son of Henry, Earl of Blackmoor. When the Pope issued the great call to crusade, Roger, left without prospects for inheritance, joined the army of the faithful and went forth to sack the Holy Land. Roger was not a particularly good Christian, but he was a remarkable crusader. Though he set out from England alone, with only his sword and his horse, by the time he reached the Holy Land, he had gathered a cohort of men around him who were fanatically loyal. Together, they fought at the forefront of the Crusader army all the way to the taking of Jerusalem. In recognition of his service, he was granted a barony in the Kingdom of Jerusalem.”

There was a brief silence, and in that time Varanus caught sight of Korbinian leaning against the wall, running his fingertips along the frame of the portrait. Smiling at Varanus, he said:

“I have a question.”

Varanus glared at him. She couldn’t respond, of course. What would Cousin Robert think?

But Korbinian was good enough to carry on:

“He says that Roger was the first Varanus. Good for him.” Korbinian spread his hands in a gesture of confusion and asked, “But what is a Varanus?”

Varanus raised an eyebrow at him. What a silly question! She was a Varanus. Grandfather had been a Varanus. Cousin Robert was a Varanus.

Then again.…

“Forgive my ignorance, cousin,” she said to Robert, “but where does the name Varanus come from?”

Roger laughed loudly and replied, “Well may you ask. I am just coming to that. During the Crusades, Roger became famous for his ferocity and rapaciousness, qualities mimicked by his men. Many of the Saracens thought him to be an agent of the Devil, possibly even the Devil incarnate. They had many names for him, none of them pleasant. Some took to calling him Al-Waran, ‘the lizard.’ When Roger learned of this, he was so pleased that he Latinized the word—Varanus—and took it as his soubriquet. And his descendants have borne the name ever since.”

“Remarkable,” Varanus said. She was not entirely certain how she felt about the origin of her name, but at least she now knew its history. “And how do the English Blackmoors come to carry it?”

“That,” Roger said, “brings us to William Varanus. Not your grandfather William, obviously, but his namesake I daresay.”

He brought her attention to a third painting, which depicted a nobleman, richly furnished and armed, seated on a horse and overlooking the Blackmoor plain. Where there ought to have been Blackmoor Manor in the background, a somber medieval keep of the Romanesque style sat upon a forlorn hill, waiting to welcome its prodigal master home. Varanus felt her breath catch in her throat for a moment as she studied the painting. Not only did he share his name, but the man depicted there even looked like her grandfather. Not that it was any real surprise. If the paintings were anything to go by, there was a tremendous amount of similarity between all of the Varanus men.

“William Varanus,” Robert said, “the first William Varanus, was the only surviving descendent of Roger Varanus. After Saladin’s conquest of Jerusalem, William—who, I might add, survived both the massacre of the Crusader army and the Siege of Jerusalem—suddenly found himself landless, and with little interest in serving a kingdom reduced to Acre and the coast, he found his way back home to England and to Blackmoor. Rather like you have done.”

“Yes, isn’t it?” Varanus asked, avoiding the sound of sarcasm. What an absurd comparison for him to make!

“His return was fortuitous,” Robert said, turning back to the portrait. “Over the intervening century between Roger’s departure and William’s return, the family at Blackmoor had suffered tremendous reduction. Once healthy, proud, and vibrant, the civil war between King Stephen and the Empress Maud had severely reduced their numbers. By the time William returned, the Blackmoor line had only daughters, and it was feared that the family would simply die out, to be superseded by a rival dynasty.”

“Ah, but a miracle,” Varanus said. It was obvious what direction the tale went. “A distant male cousin returns from a far off land, marries the eldest daughter, and keeps Blackmoor in the family.”

“I suppose the story rather writes itself,” Robert said with a laugh. “Still, it was a pivotal moment in our family’s history. If not for William, neither of us would be here. And from then onward, the Earls of Blackmoor have always called themselves by the surname Varanus.”

Varanus thought for a moment about what that meant for the age of the lineage.

“Tell me, Cousin Robert,” she said, “doesn’t that make our family and your title the oldest—at least one of the oldest—in England?”

Robert sighed and smiled. When he answered, it was in a voice touched with sadness—for effect, no doubt:

“Alas not. That is, de facto but not de jure. Our family is arguably the oldest, yes, especially if one traces the line all the way back to Henry rather than to William. Unfortunately, as far as the title is concerned, we have not held it consistently. Or,” he added, almost managing to hide a scowl behind another smile, “more to the point, the title has not existed consistently since its establishment. From time to time there have been English monarchs who, foolishly, believed that they may dispense with us. The title has been revoked several times over the centuries, and once an overly exuberant king attempted to elevate us to the status of marquess, though we soon sorted that out. Being an earl is quite sufficient. There is no need to draw undue attention to oneself, is there?”

“I imagine not,” Varanus said.

Robert motioned toward the far end of the gallery. “Come, let me show you the conservatory.”

Varanus fell into step beside him. It was tricky keeping pace with Robert’s long stride, but Varanus had much experience walking with people far taller than she.

“Tell me,” she said as they walked, “if the Blackmoor title has been revoked—repeatedly, as you say—then why has it been reinstated?”

At this, Robert merely smiled and said, “Because we are Varanuses.”

“That is not an answer, cousin,” Varanus said.

“Ah, but it is,” Robert replied. “The Varanus family is very well ensconced in our little Empire. I would have thought that Cousin William had taught you that.”

“He did. But he also taught me never to believe assertions without evidence.”

“Evidence is so very…incriminating,” Robert said with a smile. “But believe me when I say that there are a small number of families in England, the Varanuses included, without whose goodwill no English monarch has ever successfully reigned. We are England, not the Crown. Monarchs come and go. Ruling dynasties die off or are supplanted. And, as France has shown, even governments can be overthrown. But we.…” Robert’s expression grew serious, more serious than Varanus had seen it since arriving. “We remain. Undiminished.”

Varanus was silent for a moment before asking, “Does ‘we’ include me?”

It mattered little if it did or not, but she did wonder. Since the events of the funeral, she had become intensely curious about the possibility of secret societies and their relationship to her family.

“You are family,” Robert replied. “You are a Varanus. You can thank your grandfather for that. I wouldn’t have told you as much if you weren’t one of us.”

Intriguing, Varanus thought. Aloud, she asked:

“In that case, how are we to sort out the matter of the inheritance?”

Robert took her hand in his and patted it gently, but not reassuringly.

“As a family, cousin. As a family.”