Читать книгу The Man Who Created Paradise - Gene Logsdon - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

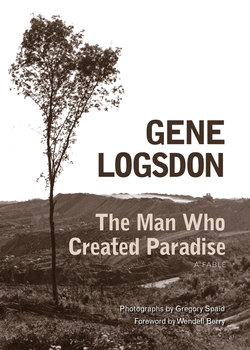

ОглавлениеThe letter stood out in sharp contrast to the others that fluttered across my desk regularly at Farmer’s Journal magazine. Handwritten on yellow, lined tablet paper, it managed to convey in just a few words both fervent dedication and humor—a rare combination. The script slanted forcefully to the right in large, generous, yet angular, almost bayonet-like letters. I imagined the writer marching forward buoyantly but resolutely toward whatever life offered—the kind of personality one might expect from a man whose last name translated from Latin meant “I hope.”

May 22, 1965

Dear associate editor Gene Blair,

Your article about how hybrid poplar tree cuttings will root and grow even on strip-mined spoil banks is exactly right. Isn’t that amazing? I mean the poplar trees, not that you are exactly right. Know any other plants that would grow well on spoil banks?

I make farms. Alice helps a lot. Alice is my bulldozer. You should stop by and take a look at what we’ve done.

Yours truly,

Wally Spero

Paradise Road

Route 4

Old Salem, Ohio

I was used to getting letters from rural people who did not bother to give me enough details to grasp their situation clearly. In their intimate worlds, farmers knew the neighborhood details, no need to elaborate. And by habit, they tended to see everyone as a neighbor—able to “stop by sometime” even though I worked in Philadelphia, at least four hundred miles away from Old Salem, Ohio. But about the statement: “I make farms,” I was mystified. If Mr. Spero was interested in spoil bank reclamation, I figured he must be using the bulldozer to level the banks or at least rearrange them into a more amenable landscape. But make farms on the strip-mined desolation of Appalachia? I had seen some of that land. One could sooner farm on the moon. I decided I would “stop by sometime.”

Working as a journalist, even on a farm magazine, or perhaps especially on a farm magazine, had not given me much cause for hopefulness about what humans were doing to the planet. My work invoked in me only an angry sadness as I watched wealth and power, in the guise of “feeding the world,” make land ownership, the lifeblood of democracy, more and more difficult for middle class people and impossible for poorer people. What coal companies did to Appalachia seemed to me no different than what agribusiness was doing to farmland, only the coal companies did it faster—in years rather than centuries.

I should never have taken a job as an agricultural journalist in the first place. Interviewing people, let alone industrial farmers intent on getting rich through land expansion, and who therefore wittingly or unwittingly were puppets in the destruction of democratic society, was a trying experience for me. I was by nature a solitary person not inclined to minding other people’s affairs. And the astounding energy of these large-scale farmers in pursuit of financial success both bored me and made me feel inferior.

But I hated even more sitting behind a desk editing vapid stories about money farming. As often as I could persuade my boss, I would travel farm country in the guise of an agribusiness reporter but hoping I would get sidetracked into something a little more inspiring. Knowing that I would hardly be allowed to spend any major time or expense writing about a man and his bulldozer on the agriculturally worthless spoil banks of Ohio, I used as an excuse for going to that region a dairy farmer who milked only twenty-five cows but earned an excellent income from them. My plan was to fly to Cincinnati, drive east and then north through Ohio’s coal-stripped Appalachia, interview the dairyman near Barnesville, then head on north of Cadiz to find Wally Spero and fly back from Pittsburgh at the end of the week. If I drove slowly, I could actually spend most of the time on the road between Cincinnati and Pittsburgh, contemplating my feelings of hopelessness and futility and trying to figure out what I ought to be doing with my life. All I really cared about was writing poetry and working a little farm, probably the two most unprofitable careers in America and so, for a poor man like me, impossible.

But far from alleviating my hopelessness, the ride became a travelog of despair. Strip-mined land was a biological horror, a farmer’s nightmare more desolate than any bomb-pitted, warred-out battlefield. It seemed to me that no machines, however powerful and gigantic, could have reduced forested mountainsides to such an extensive moonscape of bare rocks and gutted ravines. Not even the fertile, narrow little valleys between the torn hills were spared, being dotted with ugly piles of cindery-looking stuff I would learn was called “red dog” on which nothing grew, and jagged jumbles of shale which supported only stunted weeds and brush. Crossing a bridge, I noticed that the water flowing under it appeared to be orange. I backed up and took a second look. The water indeed was orange.

“H’its from iron and sulfur in the water seeping out of old mine shafts,” the serviceman at a gas station told me. After forty more miles, I grew accustomed to seeing orange ribbons of water snaking through the green brush. Kind of pretty in a horrifying sort of way.

Where coal was evidently not close enough to the surface to be stripped out, and so the land left intact, loggers had invaded the mountainsides, leaving behind clearcuts that erosion turned into tumbles of huge boulders and a few frail saplings struggling to maintain a toehold. When rain fell, what little soil remained washed downhill, and the orange creeks turned pale brown temporarily.

At the foot of these raped hills, on the narrow strips of level land between the rutted roads and the orange creeks, what I took to be the third generation of once proud mountaineers—hillbillies—stood beside their house trailers that shook at the passing of every coal and lumber truck. They stared forlornly out at me from pinched faces pocked with soulless holes where happy eyes should have been. The men were sallow-skinned and generally skinny, with bulging neck veins and sharply protruding Adam’s apples, nervous as rabbits in hunting season. The women on the other hand were mostly overweight, dumpy, hair long and stringy, with runty children hanging to them like baby opossums to their mothers. Invariably three rusting automobiles were parked beside each mobile home, two of them jacked up on logs. Junk cars, worn-out tires, and beer cans littered the roadside between the residences and spilled over the creek banks into the orange water. I learned that people stared out at passing cars so pathetically because they saw the traffic as a symbol of escape—every car speeding down the road was a life raft away from their sinking ships.