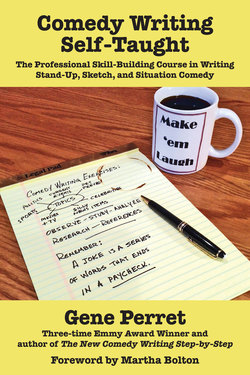

Читать книгу Comedy Writing Self-Taught - Gene Perret - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

One of the most astounding learning moments I ever experienced was prompted by a teacher who wasn’t even in the classroom at the time. He was teaching physics to a group of us in junior year in high school. We were studying electricity, and he first taught us that an electrical current passing through a coil of wire would produce a magnetic effect.

Shortly after we learned this principle, this teacher handed out to the class several doorbells mounted on blocks of wood. He also supplied nine-volt batteries and a simple button that would act as an on-off device. There weren’t enough of these supplies to go around, so he divided us into teams that would work together. Since it was the last class of the day, he told us we were dismissed as soon as we could explain how the common doorbell worked.

We were puzzled and had many questions, but our instructor ignored our raised hands and headed for the door. We asked where he was going. He said, “I’m leaving. I already know how a doorbell works.”

We looked at one another in confusion. We looked at the apparatus before us. We looked to the door, hoping the teacher would return and make some sense. He didn’t. He left us to our bewildering assignment.

My team hooked up the gear, which was fairly easy. We pushed the button, and the bell went r-r-r-r-r-r-r-ring. A brilliant classmate said, “That’s how a doorbell works—you push the button and the bell rings.” That didn’t advance the world’s knowledge of electricity.

Another student said, “We’re studying electromagnets, so that must be part of it.” He was onto something.

We played with the apparatus until we finally figured out that one of the moving parts—the part that clanged the bell—was part of the electrical circuit. When current passed through the coil, it pulled the metal clanger against some springs. But when the clanger was pulled away, it interrupted the flow of electricity. That meant that the magnet no longer attracted the clanger. The springs shot the clanger back against the bell. This closed the circuit again. This sequence repeated at a rapid rate, producing the distinctive r-r-r-r-r-r-r-ring of the bell.

This innovative teacher didn’t tell us how a bell worked. He didn’t show us, either. He simply furnished a bell, a power source, and a switch. He let us teach ourselves how the bell worked. And we did. In the process we learned much about electromagnetism and its application.

That’s the idea behind this book. It doesn’t teach you how to write a joke. It leaves you with a world full of Henny Youngmans, George Carlins, Phyllis Dillers, Jerry Seinfelds, Jay Lenos, David Lettermans, and any others you choose. It doesn’t teach you how to write sketches, but it does allow you to teach yourself using the principles exhibited by Lucille Ball, Carol Burnett, Sid Caesar, the Saturday Night Live gang, and countless others. You’ll teach yourself to write sitcoms based on the lessons available from The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Cheers, Friends, Two and a Half Men, The Big Bang Theory, and whatever other TV shows you enjoy.

The principles of electromagnetism were contained in those fundamental pieces of equipment that our teacher furnished. As one of our classmates observed, when we pushed the button, the bell rang. That showed us that the device worked and that the principles worked. Now we had to figure out how and why the doorbell worked.

All the principles of comedy are contained in the people who have practiced and are now practicing comedy. Many of them went on to legendary achievements. Again, that means the principles worked. By studying great comedy performers and superb humor writing, you can uncover secrets that will benefit your comedy creativity.

When Henny Youngman told a joke, people laughed. Why and how did he get them to laugh? That’s your assignment. When Bill Cosby is onstage telling stories about his childhood or his family, people roar. Is it the punchline he delivers? Is it the tone of his voice? Is it the facial expressions he uses? Is it all of these? With some effort, you will uncover valuable information.

The comedy principles are there for the taking, just as the idea behind a doorbell was there for my classmates and me to discover. However, there are some differences between figuring out the ringing of a doorbell and the intricacies of comedy.

First, once we solved the riddle of the ringing bell, we were done. We had conquered the mystery. We knew now that when you pushed the button the bell rang. And we knew how and why. There was no more for us to solve. The comedy-learning process, though, can go on forever. You never stop learning and you never learn enough. It’s also addictive. The more you learn about humor, the more you want to learn.

I remember once sitting with Bob Hope during a postproduction session. During a break in the work, Hope began practicing the motions of his golf swing. He mentioned that he had talked with one of the professional golfers who was playing in his tournament at the time. He said, “He told me to begin the backswing just like I’m pulling down on a rope.” He demonstrated the motion for me.

I said, “Bob, how long have you been playing golf?”

He said, “Oh, it’s over fifty years now.”

I said, “You’ve been playing golf for fifty years and you just learned that you have to pretend you’re pulling down on a rope?”

He said, “That’s the thing about golf—you never stop learning.”

That’s the thing you’ll find out about comedy, too—you never stop learning. And you never want to stop learning. The more you learn, the easier the laughs come and the bigger the laughs get.

In fact, that is the first lesson you should teach yourself right now: You must continue to learn throughout your comedy career. Learn from your own experiences and from listening to and watching others. Make yourself aware of any comedy lessons that are there for the asking.

Another difference between our high school bell research and your comedy self-education is that comedy is much more complicated and varied than ringing a simple doorbell. We had one basic device to investigate; you’ll have countless forms of humor to work with. For instance, there is stand-up comedy. In this form you write one-liners, stories, anecdotes, or whatever gets a laugh for the onstage performer. Another form is sketch comedy, such as you see on Saturday Night Live, The Carol Burnett Show, Your Show of Shows, and others. There are numerous other forms of comedy writing, such as writing situation comedies, plays, films, and humorous novels.

There are subdivisions within these forms. For instance, monologists use diverse techniques. The principles that Chris Rock would use to entertain an audience are not necessarily the same ones that Ellen DeGeneres would use. Each night we see Jimmy Fallon and Jimmy Kimmel performing a topical monologue, yet their styles are distinct from each other in several ways.

Sometimes comics who use quite similar styles show variations in the type of material they use. Henny Youngman and Bob Hope were both rapid-fire, setup-and-punchline comedians. Youngman would do jokes about his wife and mother-in-law; Hope never would.

Part of the curriculum for your self-education is deciding which mode of comedy writing you want to pursue and which style you want to specialize in.

As I said, it’s not as simple as realizing suddenly how a doorbell rings. You will study specific models in teaching yourself to write comedy. Part of your research, which we’ll get into shortly, is to find out which mentors you will choose. Another part of your research will be to analyze your own tendencies. Which style of humor do you prefer? Which comes most easily to you? Which comics or shows do you most appreciate? In order to learn to create comedy, you must also learn a little bit about yourself.

Most of your learning process will be based on studying the mentors you select, whether they are stand-up comedians, sketch shows, or situation comedies. With guidance from this book, you’re going to select, observe, analyze, and replicate the work of your mentor or mentors.

Here and there I’m also going to suggest some comedy writing exercises you can do to train your writing muscles. These exercises will help you apply the principles you’ve learned to create your own original comedy ideas. There are even more writing exercises in the companion volume to this book, Comedy Writing Self-Taught Workbook: More than 100 Practical Writing Exercises to Develop Your Comedy Writing Skills.

You may have two questions, though. First, how can a book teach you to teach yourself? That reminds me of a George Carlin line. Carlin said, “I went to a clerk in the bookstore and said, ‘Can you show me where the self-help books are?’ She said, ‘Wouldn’t that be defeating the purpose?’”

This book will give you some hints on how to teach yourself, sort of like study guides. I will advise you how to select the right mentors for you and show you what to learn from them and how to study and analyze them. You will do all the teaching and all the learning. Just like I did in high school, you’re going to have to figure out for yourself how the door-bell rings.

Second, don’t you run the risk of studying your mentor too closely? Doesn’t that hamper creativity? Doesn’t it produce a weak impersonation of a more successful, accomplished original? Trust me—studying successful comedians will only strengthen your own comedy writing skills. Learning from your mentors is the best starting point for learning solid fundamentals that have served others who have gone before.

The mentor idea is one that’s been well used in show business. Johnny Carson would openly admit that he not only admired Jack Benny, but also emulated him. When I worked with Bob Hope, he said there was a well-known vaudevillian who really fascinated him. His name was Frank Fay. I had never heard of this performer and certainly had never seen him perform. Then when we did a tribute to Bob Hope on his ninetieth birthday, someone produced footage of Frank Fay performing in vaudeville, and it was amazing how readily any observer could see that his mannerisms and delivery influenced Bob Hope. Many people find it hard to believe, but Woody Allen says that his film persona was largely a replication of Bob Hope’s character in movies. In fact, Woody Allen once produced a short film shown at a Bob Hope tribute featuring cuts between his films and some of Hope’s movies to highlight the similarities. Yet no one really thinks of Johnny Carson as a second Jack Benny, or Bob Hope as a Frank Fay impersonator. Woody Allen’s films, even though structured somewhat on Hope’s character, still remain superb examples of Woody Allen’s unique talent and creativity.

What happens when you study others, and even attempt to replicate them, is that you learn the fundamentals that made them great. However, you can’t help but add a bit of yourself to the formula. The result is a new, original, creative comedy talent.

That’s what you’re about to begin with these self-taught lessons.

Have fun learning.