Читать книгу 1970 Plymouth Superbird - Geoff Stunkard - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

THE EVOLUTION TO AERO

The former Walter P. Chrysler Museum near Detroit displays the Airflow models of the 1930s that were the forerunners to the aerodynamic stylings that arrived in the late 1960s for racing. (Photo Courtesy Quartermilestones.com)

Inasmuch as exercises in automotive styling were usually done by designers, it is fitting that something as outrageous as the Plymouth Superbird emerged from the engineering side of the Chrysler Corporation. After all, Walter P. Chrysler’s own personal interest in how and why things worked had been part of the company’s DNA since its 1924 founding. Moreover, the first scientific aero-restyling in the automotive realm was the Chrysler Airflow of the 1930s. The victim of being “too much too soon” in its overall innovations, the Airflow effort could conceivably be seen as the grandfather of what came to pass when the company threw away normalcy in the pursuit of scientific success years later, even though the latter occasion was based on a much narrower purpose: winning races.

THE POST-WAR BOOM AND THE TOWNSEND ERA

Following World War II, peacetime brought about a huge interest in motorsports. Participation grew exponentially in amateur and professional auto racing. Regardless of the form of the contest, after sheer horsepower accomplished all that was possible, engineers and racers began to think about aerodynamics. They quickly realized that there was something to it and that aerodynamics could take a competitor back to the front of the pack. Without fully realizing it, “Big Bill” France and his National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) circuit likely played the biggest role in what turned Detroit’s attention to aerodynamics in production cars. France’s monstrous new paved race course in Daytona Beach was a showcase of factory pride from its 1959 opening.

The Superbird was similarly created as a testament to pure function, as restorer John Balow demonstrates at Bristol Motor Speedway. (Photo Courtesy Quartermilestones.com)

Soon after, Chrysler’s board of directors selected a former outside auditor and then-current comptroller named Lynn Townsend to take the reins of the firm in July 1961. Although the company was in the red financially, Townsend recognized what it meant to see a car from Chrysler’s stables show its prowess on the Daytona track. In October 1961, he authorized a new racing-focused group at Chrysler Engineering to develop competition packages for both NASCAR and drag racing.

That done, Chrysler’s longtime racing liaison Ronney Householder went to Highland, Indiana, and hired his former Indy car associate Ray Nichels and driver Paul Goldsmith to help spearhead Chrysler’s NASCAR development. Formerly with Pontiac, Nichels was a skilled fabricator and seasoned race team owner. He became the primary developer of engineered components for Chrysler’s circle track program as well as its distributor to other teams.

As a brand, Plymouth already had one of the most noted names in the Grand National series. This name, of course, was Petty. Lee Petty posted season championships during the previous decade and also won the first big race at the new Daytona 500 track in 1959. Racing in a full-size Plymouth, he was badly injured in a crash at the same Daytona event during qualifying in 1961. After his son Richard took over driving full-time, the team became Chrysler’s primary full-time campaigner.

Owner Ray Nichels and driver Paul Goldsmith were hired by fellow Indy car luminary Ronney Householder, who had headed up Chrysler’s racing efforts since the 1950s. Goldsmith put this Plymouth on the pole for the 1964 Daytona 500. (Ray Mann Photo, Courtesy Cal Lane)

With Nichels and the factory responsible for development and the Petty crew (along with other campaigners) taking care of the week-in/week-out real-world testing, the work to win races as a corporation began in earnest. Chrysler had already moved to its unitized construction chassis design, eliminating the need for a heavy full frame. Meanwhile, engineers led by Tom Hoover, a Penn State–trained physicist who loved hot rodding as a hobby, had taken the RB-series Chrysler engine to its most functionally practical limits for racing. They laid plans to reintroduce the legendary Chrysler Hemi-design cylinder head to the roaring 1960s.

THE NEED FOR SPEED

Townsend wanted a winner for Daytona by 1964. Beginning in March 1963, Hoover and his crew set their sights on taking the first-generation Hemi cylinder head and adapting it to a revised extreme-duty RB engine block for that purpose. Working under a very tight schedule, these engines were hand-fitted and tested rigorously. Using the latest versions on February 23, 1964, Richard Petty led Jimmy Pardue and Paul Goldsmith to a 1-2-3 finish for Plymouth at the Daytona 500.

Richard Petty laps the #7 Ford driven by Bobby Johns in the 1964 Firecracker 400, thanks to the Hemi and the smaller frontal area of the 1964 Plymouth B-Body design. (Ray Mann Photo, Courtesy Cal Lane)

In stock car racing, Chrysler’s chief competitor was Ford Motor Company, as General Motors had formally dropped out in 1963. Ford had stuck with full-size cars, and partway through the 1963 model year, the company released a newly updated version of the Galaxie XL with a restyled roof shape and sloped rear roofline. Although it was not a true fastback to the rear valance, this fastback execution was for the direct benefit of downforce at circle track speeds. Credit therefore deserves to be given to this Total Performance 1963½ Galaxie and the associated Mercury Marauder as the first true hint of what became the 1960s aero-wars between Ford and Chrysler.

Chrysler actually had taken a different tack. The Dodge and Plymouth B-Body designs had been revised for 1964, featuring a narrower, lower, and shorter profile than the full-size Ford. They also featured flush grille work and a backswept rear cab design fitted with either slanted or curved glass. Because no other formal roofline was offered beyond a hardtop or pillarless coupe layout, there was no declaration of the car’s inherent aero efficiencies. However, the history of Chrysler in NASCAR for 1964 and the legacy of the new 426 Hemi might have been a bit different had these things not been coupled to that engine’s introduction.

Don White’s newly released fastback 1966 Dodge Charger was perhaps the first to truly benefit from subtle changes learned by the Special Vehicles Group. (Ray Mann Photo, Courtesy Cal Lane)

The differences became a source of contention between the companies as well as the sanctioning body. At the end of 1964, France decided to ban the Hemi as a non-production engine as well as force Chrysler to run full-size bodies. Householder called his bluff and boycotted the series for 1965. After France relented due to the Street Hemi’s upcoming release, Ford boycotted NASCAR for part of 1966. Nevertheless, the aero wars continued.

In 1966, Dodge released a new fastback model called the Charger, which did take the rear cab slope literally to the back bumper. The problem was lift. Because the air sailed directly off this surface, the air wanted to pull the back of the car off the ground at higher speeds. The solution was a small deck-mounted spoiler that created enough downforce to address the problem. It gave Sam McQuagg’s Charger a victory at Daytona’s Firecracker 400 that summer and David Pearson won the 1966 Grand National championship. The Plymouth Belvedere, such as the one Richard Petty drove, appeared to be a box on wheels. However, it could be “raked” to help downforce, and held its own well. Petty won the Daytona 500 in the rain the previous winter.

Richard Petty’s Belvedere won the 1967 Grand National title; shown here in restored form outside at the Petty Museum. (Photo Courtesy Quartermilestones.com)

By now, Chrysler had begun studying scientifically provable aerodynamic ideas. Working in a Special Vehicles Group started in 1964 under Larry Rathgeb, John Pointer left the company’s missile group and government work to join them. Bob Marcell arrived from the aerospace research lab at the University of Michigan. George Wallace, who possessed a brilliant mind and who played a pivotal role in this era of Chrysler’s racing effort, was also there, along with Dick Lajoie, John Vaughn, and others.

Even though the 1967 Belvedere did not appear as slick as the Fords or Dodges, with gentle massaging here and there, it was slick enough, and Richard Petty was plenty talented. He won 27 races that season, including a string of 10 consecutive, and sealed the legacy of King Richard in NASCAR lore. Petty won the championship, Dodge won 5 other race titles, and Jim Paschal won 4 more for Plymouth, giving Chrysler 36 wins on the 49-race tour.

WIND TUNNELS

With superspeedway speeds now requiring more direct understanding, especially about what occurred during drafting (when cars were close together at more than 170 mph), the company decided to begin aero-testing in two facilities. The scaled-down wind tunnel at Wichita State University in Kansas and Lockheed’s full-size aircraft development tunnel in Georgia were rented, and the first cars involved were the 1968 models of the Charger and the Road Runner.

The stylists were rightly proud of their new Charger, with its inset and blacked-out grille, which looked like a big spaceship intake. To make room for the trunk, the rear window slanted steeply off the roofline between two long roof-to-body extensions. From the side, they made the car appear to be a fastback. The wind tunnel work showed that the grille was indeed a big scoop, and gave the Charger a lift rate of 1,250 pounds as air tried to escape from underneath the car. Meanwhile, the back window, with its flying buttress edges, caused air to shoot upward off the surface, working (quite literally) to pull the rear wheels off of the ground.

Bob McCurry, who headed Dodge at the time, wanted a winner. The stylists were not happy with seeing their work changed, but in spring 1968, McCurry approved a redesign called the 1969 Charger 500. This used a 1968-type Coronet grille to make the front of the car flush and a plug along with a much smaller deck lid to angle the rear window to the same angle that the bodyline flowed from the roof. The name was given for two reasons. The first was for its debut at Daytona for the 1969 season. The second was that the Automobile Competition Committee for the United States (ACCUS), the governing body of motorsports rules making, stated that a minimum quantity of 500 units of a given model must be built to be legal.

The new 1969 Charger 500 with its fastback window was announced in mid-1968 for a debut at the 1969 Daytona 500; the Fords proved to be a bit quicker and Dodge returned to the drawing board. Tim and Pam Wellborn formerly owned this Hemi example. (Photo Courtesy Quartermilestones.com)

The 1969 Ford Talladega was the reason Richard Petty made a one-season switch to Ford blue. Otherwise, Plymouth would not have committed the resources in late 1969 to build a truly competitive race car. (Photo Courtesy Quartermilestones.com)

For Richard Petty, 1968 proved to be a somewhat bittersweet follow-up to his dominating 1967 season. Ford released a new fastback called the Torino; Mercury offered an associated model named Cyclone. With less frontal area than Chryslers, they were slick enough to dominate most of the year. The wind tunnel work on Petty’s 1968 Road Runner showed that it was competitive thanks to its own flush grille and rear window. Therefore, when the Charger 500 was announced in June, he asked Plymouth what they planned to do for 1969.

The response was, “Nothing.” Plymouth felt that the Road Runner was already a good fit and believed that Petty could still win in it. Ford, meanwhile, had just announced and received ACCUS approval for a newly designed aero styling package for the Torino called Talladega, named for a new NASCAR track Bill France was constructing in Alabama. This car (and companion Cyclone Spoiler) took the functionality a step further, with a deliberately dropped and extended nose and smoothed-out rear cab design.

Petty was now more alarmed and requested to move to Dodge to run a Charger 500 for the upcoming season. Neither Dodge, who had enough big-name drivers already, nor Plymouth, who frankly had no other big-name drivers, were interested in this change. Phone calls were made to Dearborn, contracts were let, and at the end of the 1968 season, Petty Enterprises announced that the number 43 would be on a Ford for 1969. Plymouth had no back-up plan for this consequence.

WINGS AND “THE SUMMER OF ’69”

For Bob McCurry, it was the hope that Dodge could finally win the Daytona crown. He had a car, the Charger 500. He had four drivers: Bobby Isaac in the Harry Hyde #71, Buddy Baker in Ray Fox’s #3, Cotton Owens’s #6 driven by Chargin’ Charlie Glotzbach, and Paul Goldsmith in Ray Nichels’s shop car #9. Alas, LeeRoy Yarbrough, in a Torino Talladega owned by Junior Johnson, won by inches when Glotzbach could not pass him on the final lap. Bob McCurry was not happy. At all.

During the run-up to the event, John Pointer and Bob Marcell had each sketched out the next generation car in theory. Convention did not matter; only function mattered. The plan was to add a quite pointed nose rather than one that simply sloped. In addition, instead of a small deck spoiler, they wanted one of enough consequence to literally plant the back end of the car to the racetrack. With McCurry on the warpath, they showed him the rudimentary ideas.

“It’s ugly,” he reportedly said to the aerostylists, then added, “Will it win?”

They told him, “Yes, it would.”

That settled, he gave it his final approval, and it was a no-holds-barred chase for its release. Work began in earnest using everything learned in the Charger 500 program to add an extended nose and figure out the spoiler design. This became more critical when noting that ACCUS intended to meet in late April 1969 to re-evaluate production numbers.

A number of things were discovered during this development process. Once the nose was configured properly, a set of front fender scoops was authorized for tire clearance, but they actually functioned more as air extractors. The rear wing was designed with an inverted Clark Y-style aircraft horizontal spoiler. It was styled high enough to clear the open deck lid. Using a pair of rear-fender-mounted streamlined uprights actually made this wing even more functional; the upright’s slab-sided shape was capable of straightening out the car in the event of drifting or air speed coming from anywhere but the front.

The requisite number was again 500, with six months advance notice given. As a result, the new Charger Daytona was formally introduced and shown to the press in the middle of April, with the implicit desire to have it debut at the new Talladega track in mid-September. ACCUS ruled mere weeks later that the new minimums going forward were one unit for every two dealerships.

The next step forward was a moonshot; the 1969 Charger Daytona looked like nothing that had ever appeared from any manufacturer. This Omaha Orange example, in the vicinity of an airplane propeller, was once in the Wellborn Museum’s collection. (Photo Courtesy Quartermilestones.com)

The cartoon on the wing notwithstanding, Plymouth’s Superbird was all business. (Photo Courtesy Quartermilestones.com)

The Daytona was truly an exercise in function; its look also had novelty and Dodge rode that wave into its dealerships as the cars began to show up in the latter half of 1969. Created from the normal Charger R/T packaging, all Daytonas were Hemi- or 440 Magnum–powered. In most cases they offered minimal extra options and base sold for little more than the conventional Charger R/T.

To facilitate construction as quickly as possible, Dodge turned to a Detroit-area fabrication firm, Creative Industries. Having worked on the Charger 500 program as well, Creative was tasked with constructing and installing the noses and wings, and making other changes to Charger R/Ts created on the assembly line. This included a large wraparound rear “scat stripe” that read “DAYTONA.” Working with engineer Dale Reeker from Chrysler, the parts were rapidly designed and all production issues dealt with quickly. Some immediate problems cropped up from the stylists, until McCurry stepped in and told them to shut up and back off. The Daytona arrived in time to help inaugurate the first race run at the Alabama International Motor Speedway in Talladega. It also won there.

Meanwhile, although Richard Petty had won a couple of races in his new Ford, it was not a great romance. Like Dodge, Ford had its own share of superstars, and they tended to get preferential treatment. The Petty team’s long experience with Chrysler Hemi engines no doubt aided them as Ford’s new Boss 429 had also arrived for 1969, and having the aero-styled Torino body was likely better than trying to tool around at 180 mph in a Road Runner, even if that vehicle had been named Motor Trend’s Car of the Year in 1969.

When Petty made statements that life was not perfect, Plymouth quickly got the hint. In June, some Chrysler people made quiet inquiries as to whether Mr. Petty would be interested in discussing a future back with Plymouth. He would. If they built a competitive aero-model, he would come back, but there would be a cost. In addition to money for racing Plymouths again, Petty Enterprises would also receive the corporation’s entire circle track parts distribution and contract-racing business for which Ray Nichels/Paul Goldsmith were currently responsible. The authorization for that change reportedly went all the way to Chairman of the Board Lynn Townsend, who signed off on it.

The new ACCUS minimum requirement meant that Plymouth needed to build almost 2,000 units. Changes in federal headlamp laws, slated to go into effect on January 1, 1970, meant that the Daytona-type concealed headlamp design had to be off the assembly line before then. The stylists intended to get some comeuppance for Dodge’s indiscretions, and took some. To top it off, the company had just six months to pull it all off.

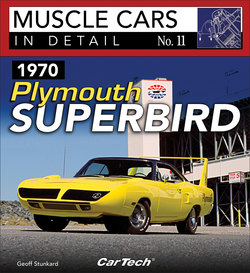

The result was the Plymouth Superbird.