Читать книгу Draca - Geoffrey Gudgion - Страница 31

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

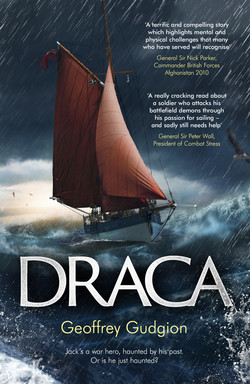

I: GEORGE

ОглавлениеGeorge Fenton enjoyed early mornings at Furzey Marina. She ’ d take a start-of-the-day turn around the boatyard, seeing who was around, while she savoured the plinkplinkplink noise of halyards slapping against aluminium masts in the wind. The sound always made her smile inside and think ‘ Why the feck aren ’ t I on the water? ’ but she didn ’ t sail at weekends. Weekends were for rich folk who could afford to keep a boat idle during the week while they made their dosh : the clients who expected her and Chippy Alan the shipwright to work their arses off looking after them. There was always something that needed fixing before they could put to sea, and there was usually someone she wanted to find, like when they hadn ’ t paid their bill.

It was mainly couples at weekends. A friendly bunch, for the most part. The men would smile at her boobs and forget they had a tide to catch. The women in their wake would roll their eyes in a way that reminded George of a stained- glass window she ’ d seen in a church : some martyred saint with her eyes on heaven and a big, open ‘ O ’ of a mouth. She ’ d looked as if she was only pretending to be suffering, and really having way too much fun under her robes.

George didn ’ t like strangers wandering around the boatyard. Stuff went missing, and she had to answer to the owners even though she was just the Office Manager. So when she saw some guy put a ladder against Mad Eddie ’ s boat she swore to herself and wandered over. Draca had been beached for years, propped up on timber legs on an old, tidal hard at the edge of the boatyard. Mad Eddie Ahlquist had paid the yard to unstep her broken mast, take out her ballast and float her in at the top of a ‘ spring ’ tide. She ’ d been there ever since, with her ballast put back to hold her down. She wetted her keel every tide and looked sorrier whenever George strolled that way. Green, slimy stains ran down her cheeks from her hawsepipe at the bow and from the cockpit drains under her counter, so that she looked like she was crying at one end and shitting herself at the other.

By the time she reached Draca , the man was leaning over the gunwale like a bum on stilts. When she challenged him he came down the ladder slowly, one rubber-booted step at a time, as if he was unsure of his footing.

‘ Jack Ahlquist, ’ he introduced himself. That checked her. She ’ d been about to get all aggressive. Now he ’ d turned, she could see the likeness. Same shoulders, same Nordic cheekbones. And totally fit enough for a girl to put her shoulders back.

‘ George Fenton. ’

He blinked at the ‘ George ’ .

‘ My mum called me Georgia. George seems to have stuck. I ’ m also known as Georgie Girl to my more sexist customers, and the Boatyard Bitch to the ones what don ’ t pay their bills. ’ She was talking too much.

He had a nice smile. ‘ This is my grandfather ’ s boat. ’ He touched the hull and frowned at the smear his fingers left in the dirt.

‘ Then tell him to let us do some work on her. It ’ s a crying shame to leave her like this. ’ The dirt matting the hull would wash off. Other decay might be more fundamental.

‘ I would if I could. He ’ s dead. ’ He turned, pretending to move away from the ladder, but probably hiding his face, like he was being brusque to mask his feelings.

George wasn ’ t surprised about Eddie. She made sympathetic noises at Jack Ahlquist ’ s back, but she ’ d known it was coming when she last saw him, around Christmas. They ’ d had a weird conversation about rigging a jury mast in Draca so that she could carry a square sail again and put to sea like a Viking longship . Just one trip, he said. He never did anything about it, though. That day he ’ d asked Chippy Alan to unstep the figurehead, and he ’ d taken it away with him. George thought about Eddie, afterwards, because he reminded her of her m um before she died. Masses older than her, of course, but when George shut her eyes there ’ d been a greyness about Eddie in her mind. Not the grey of age, which can be quite healthy, but a dark, sick grey turning black at the edges. George knew what that meant. She ’ d seen it in her mum . The black takes over and then they die.

Now here was his grandson. An outdoorsy type, maybe an Aries.

‘ Got the key? ’ she asked him. ‘ Want to look? ’

He hung back, so she went up the ladder first and regretted it halfway up when her shorts and bare legs went past his face. She looked down from the top, half expecting Jack to be staring up at her bum, but he was touching the hull again with his fingers splayed to show his wedding ring. George got the message. Arrogant sod. More of a Taurus, perhaps. She turned away as he began to climb.

Draca was a fair size : at least twelve feet in the beam and perhaps forty in length, plus her bowsprit, and flush-decked, with just the cockpit, a ‘ doghouse ’ cabin hatch and a skylight to break the sweep of teak. When George had first come to the yard about four years before, Draca ’ s deck had stretched away like a dance floor. Now it was a lumberyard of spars, draped with ropes. Drifts of leaf pulp had blown into corners, rotted and grown seedlings. Then, she ’ d had a mast and rigging. Now, she was a hulk.

Jack moved aft unsteadily, at a crouch, keeping well away from the edge. True, it was about twelve feet down to the hard, and there was only a shin-height wooden rail, but he looked nervous, like he was unsure of his footing. When they reached the cockpit, they found it half- full with a dirty scum of water, deep enough to cover the gratings and lap over the top of Jack ’ s boot as he stepped down into it. He didn ’ t seem to notice. The drains must have been clogged with leaves or debris, and he had to wade around in a mess of sodden rigging that had probably been there since they took out the broken mast.

‘ Shall I lead on? ’ Jack fumbled for the key, his boots trailing water as he stepped over the companion ladder coaming. George slipped off her trainers.

‘ How old is she? ’ She ’ d never been below deck in Draca . Her mast had sprung the last time Eddie took her out, which was soon after George arrived, and she ’ d been laid up ever since.

At the bottom of the steps, Jack turned in a space that had a chart- table to starboard and was cramped by a large, cast-iron engine casing just off the centre-line to port. George had seen similar spaces in other, classic boats, a kind of working ‘ wet space ’ where the watch on deck could come in oilskins and boots to look at charts or make a brew.

‘ Nineteen oh-five. One of the last of the sailing pilot cutters. ’

‘ What kind of engine is that? ’

‘ That, ’ Jack said, ‘ is Scotty. ’ He made it sound like a pet dog.

‘ As in “Beam me up, Scotty ” ? ’

‘ Nah . As in good, Glasgow engineering. Pre-war vintage. ’

‘ And it still works? ’

‘ It used to. Bit temperamental. Grandpa wanted to change the ship as little as possible, so he kept it. ’

Jack tapped a narrow door, port side, forward of the engine. ‘ Heads in there. Bit cramped. Fold- down basin and no shower. Foul- weather gear on the other side. ’

He swung open mahogany double doors and went forward into the saloon, leaving a trail of wet footprints. He seemed even taller, now she was barefoot, and broad enough to fill the doorway. She followed, and stepped into an atmosphere.

Classic boats are like old buildings; sometimes you can sense a mood. When George was little, her mum used to drag her round stately homes where she ’ d gawp at the silver and oil paintings and lawns, and once in a while George would pick up an atmosphere. Happy ones, sad ones, downright creepy ones, maybe all of those in different rooms, and usually stronger in places like the nursery or the servants ’ rooms in the attics. Hardly ever in the grand, gilded staterooms. Her mum said it was because she was psychic and born with a caul over her head, but then her mum had some pretty weird ideas. George just knew that people leave something of themselves when they go.

She shivered, and tried to persuade herself it was the damp. The saloon was musty. It looked and felt empty. Book racks with no books. An old, iron stove, black and cold like the coal scuttle beside it. Teak woodwork, dark with age, grey with dust.

‘ Sleeping cabin through here. ’ Jack had to stoop beneath the deckhead. He opened a narrower door in the forward bulkhead, to one side of the stove. George peered around him at a cramped space with a single berth port side, and a narrow double to starboard. Both had leeboards fitted to stop you falling out in rough weather, and they looked coffin-deep without their mattresses. A hole in the deckhead showed where the mast had been. A tarpaulin had been stretched over the gap, but damp had come in just the same, making a puddle of slime on the deck around the void where the mast had been stepped.

‘ This was my bunk, as a boy. ’ Jack put his hand inside the single berth and felt upwards, making a metallic rattle against a curtain rail. Leeboards and curtains, very cosy. The atmosphere was stronger here. Soon she ’ d be able to put a name to it.

‘ Can you imagine what it was like, for a boy? ’ Jack ’ s smile broadened into a grin, his guard slipping. ‘ Sailing off to adventure? Channel Islands? One summer we went round Brittany into Biscay. ’

‘ Just the two of you? ’ She was a big boat for two people to go cruising in , especially if one of them was a kid.

‘ When I was older, in my teens perhaps. Day sailing only, and Grandpa was stronger, back then. We both knew what we were doing. ’

‘ People say he was a pretty wild sailor. Took risks. ’

‘ Not with me, he didn ’ t. ’ Jack sounded defensive.

‘ It was before my time, anyway, ’ George shrugged. ‘ Chippy Alan would know, if you want some local stories. ’

‘ Chippy Alan? ’

‘ Shipwright. Works here … ’ She stopped when she saw loss in his eyes. ‘ You really loved him, didn ’ t you? ’

‘ Grandpa … ’ Jack ’ s voice faded away then started again, more strongly. ‘ Grandpa opened up horizons. He gave me permission to be myself. ’ He turned away.

‘ Fo ’ c ’ s ’ le through there? ’ George nodded at another door, leading further forward. Jack pushed it open.

‘ Stores. Sail lockers. There ’ s another pull-down bunk in there, but it ’ s not comfortable. It ’ s where they put the paid hand when the owner employed a crew. ’

The ‘ bunk ’ wasn ’ t much more than five feet long, wedged in behind a thick metal pipe that must have run from the anchor on deck to the chain locker below.

‘ I suppose that ’ s what they mean by sailing short- handed, ’ she quipped.

He had a smile that started small but broadened, lifting his face. George felt she ’ d been given a glimpse of a sweeter person hiding inside that dour exterior.

‘ So I ’ d have one hull of a problem. ’

And he could come back at her. It wasn ’ t great humour from either of them, but it broke the ice. Then she remembered his wedding ring and led the way back into the saloon.

‘ Will your family restore her? She ’ d be worth a fortune, done up. ’

‘ Grandpa wants to be cremated on board, at sea, and for Draca to be scuttled. ’

‘ Feck, what a waste! ’

‘ It ’ s also illegal. I checked. The authorities aren ’ t keen on half- burned bodies washing up on the beaches. Besides, ’ he ran a finger over the table, leaving a shiny trail through the dust, ‘ I don ’ t think I could do it. This ship is Grandpa. He bought her as a wreck and spent years restoring her. It would be like killing him all over again. ’

The atmosphere in the boat caught George for a moment, and she shivered again. It lurked in the background, just enough to make her uncomfortable. She sniffed, trying to make it out, but smelled only damp and rot and a hint of stale tobacco. It was as if she was in someone ’ s house without permission, knowing that the owner would be back soon. She stood still for a moment, trying to decipher this mood, and lifted her fingers to touch a deckhead beam. Here, where the dust hadn ’ t settled, the wood glowed a rich, dark honey. The impression was stronger through her fingers, and she closed her eyes, listening. She had the sense that if that absent owner came back, he wouldn ’ t like her and she wouldn ’ t like him, but the boat was waiting for him. And it was definitely a ‘ him ’ .

Weird. Jack Ahlquist was standing beside her as she opened her eyes and dropped her hand, watching her with grey, gentle eyes that looked tired in the shadows of the cabin. She turned and made for the companion ladder up to the deck, still not sure why the boat made her so uncomfortable. Anyway, she had a boatyard to run.