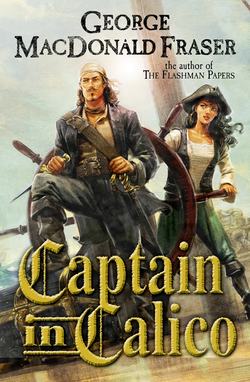

Читать книгу Captain in Calico - George Fraser MacDonald - Страница 12

6. ANNE BONNEY

ОглавлениеThe woman in the carriage was tall, and quite the most vivid-looking creature Rackham had ever seen. Her hair, beneath a broad-brimmed bonnet, was glossy dark red, and hung to shoulders which in spite of the heat were covered only by a flimsy muslin scarf. Her high-waisted green gown was cut very low on her magnificent bosom, which was bare of ornament; her face was long, with a prominent nose and chin, her brows heavy and dark, and her lips, which were heavily painted, were broad and full, with an odd quirk at the corners that gave her an expression at once wanton and cynical. Massive earrings touched her shoulders, there was a tight choker of black silk round her neck, and the bare forearm which lay along the edge of the carriage was heavily bangled and be-ringed.

‘In God’s name, Penner, what was the meaning of that moon madness?’ She waved a jewelled hand in Rackham’s direction. ‘D’ye value the hide of your friend so cheap that you’ll offer him as meat for a bully-swordsman’s chopping?’

‘Why, ma’am, I—’ Penner shuffled and stammered. ‘I was opposed to it, d’ye see – from the outset, but—’

‘If that was your opposition, God save us from your encouragement,’ observed the woman languidly. She turned her heavy-lidded eyes on Rackham. ‘For one who has so narrowly cheated the chaplain your champion is mighty glum,’ she observed. ‘He has a name, I suppose?’

‘Hah, yes,’ said Penner. ‘My manners are all to pieces, I think. Permit me, ma’am, to present my friend and brother officer, Captain Rackham – Captain John Rackham.’ He made a vague gesture of introduction. ‘John – er, Captain, – Mistress Bonney.’

Rackham, still resentful of this red-haired Amazon, gave a nod which was the merest apology for a bow. Covered with dust and sweat, he was conscious of the bedraggled figure he must present, and his indignation was not sufficient to make him forget his vanity.

But Mistress Bonney had no thought for his disarray. Her eyes widened at the mention of his name.

‘The pirate captain? He that fired on the Governor’s fleet and took a fortune in silver from the Spaniards?’

‘The same,’ said Major Penner, with the proud air of a master exhibiting a prize pupil. ‘And now turned privateer with me.’

Mistress Bonney’s grey eyes beneath those heavy black brows considered Rackham appreciatively. Her broad lips parted in a smile. ‘Faith, it’s an honour to meet so distinguished a captain. I had heard you took the pardon this morning. Doubtless you mean to lead a peaceful life ashore.’

She was laughing at him, and he flushed angrily. ‘You hear a deal, madam. But it’s not all gospel. If they tell you I fired on the King’s ships they lie: it was no work of mine but that of a half-drunk fool. Nor did I take any silver from the Spanish. That, too, was another’s work.’

‘Another half-drunk fool?’ she asked, smiling.

‘A cold sober traitor,’ he answered.

She pursed her lips, her eyes mocking him. ‘You keep sound company. And now you are in league with the bold Major. Well, he’s neither fool nor traitor, but for the rest he’s both drunk and sober, as the mood takes him. Am I right, Major?’

‘As always, ma’am,’ replied the Major gallantly. ‘And never more drunk than in the presence of beauty.’

‘A compliment, by God! Put it in verse, Major, and sing it beneath a window.’ She turned back to Rackham. ‘You, sir, who are a captain, and a pirate, and what not: where did you learn to use a sword so pitifully?’

‘Pitifully?’ Rackham stared, then laughed. ‘Ask La Bouche if my sword-play was pitiful.’

‘I’ve no need to ask. I’ve eyes in my head. You’re a very novice, man. La Bouche might have cut you to shreds.’

‘But he didn’t, ma’am, as ye’ll have observed,’ put in the Major hastily, as he saw Rackham’s brow growing dark. ‘Captain Rackham is not one of your foining rascals; a quick cut and a strong thrust is his way – and very effective, too.’

‘It may be. But he can thank God and his good luck that he has a whole skin still,’ said Mistress Bonney. ‘And where do you take him now?’

‘To my house,’ said the Major. ‘He has a scratch or two that will be the better of bathing and sleep.’

‘And what do you know of tending his scratches?’ she asked scornfully. Her lazy glance lingered again on Rackham. ‘You’d best let me see to him. Climb into the coach, both of you, and we’ll take him where he won’t be mishandled by some coal-heaver who calls himself a physician. For that’s the best he’d have from you, Penner.’

The Major looked uneasily at Rackham. ‘If you think it best—’ he began. Mistress Bonney waved him aside impatiently.

‘Be silent, man. It’s for Captain Rackham here to judge.’

Rackham met her bold stare and wondered. His first instinct was to tell this fantastic woman, with her harlot’s face and body and mannish tongue, to mind her own business and be gone. She was too bold; too forthright. He could have excused her that if she had been a tavern wench, but she was not. There were the signs of wealth about her, and her voice, for all its oaths and masculinity, was not uneducated. These things, taken with her heavy paint and challenging eyes, made her a queer paradox of a woman; instinct warned him that she was dangerous. But his hand and side were stinging most damnably, and his head throbbed. And so he made the decision which was to change the course of his life, with two words.

‘Thank you.’ He turned to the Major. ‘If Mistress Bonney has anything that will take the ache from these cuts, I’d be a fool to refuse.’

The Major nodded solemnly. He seemed vaguely unwilling, but Rackham was too tired to take notice of him.

They drove up the slight incline through the town, and then the coach wheeled to take the eastern coast road. Lulled by the gentle rocking of the vehicle, Rackham leaned back and allowed his tired body to relax. Soon they were passing through the cane-fields, with their gangs of black slaves working in the blazing sun. Somewhere one of them was chanting in a deep, strong voice, and Rackham closed his eyes and dozed to that slow, haunting melody.

The stopping of the coach shook him out of his half-sleep. They were through the cane-fields now, and were halted on a stretch of road which ran through a quiet palm-grove.

Major Penner had climbed out of the carriage, and looking about for explanation Rackham noticed a small drive winding between the palms to a white, green-shuttered house half-hidden among the trees. Penner was looking uneasy and fidgeting with his hat; he was, apparently, bidding good-bye to Mistress Bonney. Rackham could make nothing of this.

‘Is this your house?’ he asked her.

‘Not yet. I recollected I had a call to make on Mistress Roberts – hers is the house yonder – and Major Penner has gallantly offered to carry a message for me. It is vastly obliging of him. I don’t doubt that Fletcher Roberts will bid him to dinner.’

Her explanation was sounding oddly like a series of instructions; the Major could hardly have looked less gallant or obliging.

‘I shall look for you again, Major,’ she continued, and although she favoured him with her most gracious smile there was finality in her tone. ‘In the meantime have no fear for your charge.’ And before Rackham could speak the carriage was rolling off and Penner was left standing by the roadside.

Rackham half-turned in his seat to call the driver to halt, but the sudden movement brought a fiery wrench to the wound in his side, and he sank back, gasping with pain. Mistress Bonney, seeing him go suddenly pale, started forward in her seat, only to relax as he lifted his head angrily.