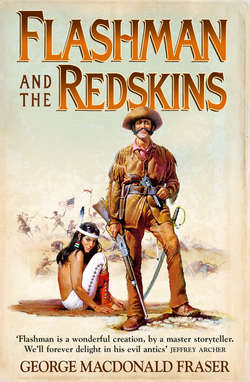

Читать книгу Flashman and the Redskins - George Fraser MacDonald - Страница 13

ОглавлениеI never did learn to speak Apache properly. Mind you, it ain’t easy, mainly because the red brutes seldom stand still long enough – and if you’ve any sense, you don’t either, or you’re liable to find yourself studying their system of vowel pronunciation (which is unique, by the way) while hanging head-down over a slow fire or riding for dear life across the Jornada del Muerto with them howling at your heels and trying to stick lances in your liver. Both of which predicaments I’ve experienced in my time, and you may keep ’em.

Still, it’s odd that I never got my tongue round it, for apart from fleeing and fornication, slinging the batfn1 is my strongest suit; well, I speak nine languages better than the natives, and can rub along in another dozen or so. And I knew the ’Paches well enough. God help me; I was even married to one for a spell, banns, beads, buffalo-dance and all, and a spanking little wild beast she was, too, with her peach-brown satin skin and hot black eyes, and those white doeskin leggings up to her thighs with the tiny silver bells all down the sides … I can close my eyes and hear them tinkling yet, sixty years after, and feel the pine-needles under my knees, and smell the woodsmoke mingling with the musky perfume of her hair and the scent of the wild flowers outside her bower … the soft lips teasing my ear, murmuring ‘Make my bells ring again, pinda-lickoyeefn2 …’ Aye, me, it’s a long time ago. But that’s the way to learn a language, if you like, in between the sighs and squeals, and if it didn’t happen in this case the reason is that my buxom savage was not only a great chief’s daughter but Mexican hidalga on her mother’s side, and inclined to put on airs something peculiar, such as speaking only Spanish in preference to the tribal dialect of the common herd. They can be just as pert and hoity-toity in a Mimbreno wickiup as they can in a Belgravia drawing-room, believe me. Fortunately, there’s a cure. But that’s beside the point for the moment. Even if my Apache never progressed far beyond ‘Nuetsche-shee, eetzan’, which may be loosely translated as ‘Come here, girl’, and is all you need to know (apart from a few fawning protestations of friendship and whines for mercy, and much good they’ll do you), I still recognise the diabolical lingo when I hear it. That guttural, hissing mumble, with all its ‘Tz’ and ‘zl’ and ‘rr’ noises, like a drunk Scotch-Jew having trouble with his false teeth, is something you don’t forget in a hurry. So when I heard it in the Travellers’ a few weeks ago, and had mastered an instinctive impulse to dive for the door bawling ‘’Pash! Ride for it, you fellows, and save your hair!’, I took stock, and saw that it was coming in a great spate from a pasty-looking specimen with a lordly academic voice and some three-ha’penny order on his shirt front, who was enthralling a group of toadies in a corner of the smoking-room. I demanded to know what the devil he meant by it, and he turned out to be some distinguished anthropologist or other who had been lecturing to the Royal Geographic on North American Indians.

‘And what d’you know about them, apart from that beastly chatter?’ says I, pretty warm, for he had given me quite a start, and I could see at a glance that he was one of these snoopopathic meddlers who strut about with a fly-whisk and notebook, prodding lies out of the niggers and over-tipping the dragoman on college funds. He looked taken aback, until they told him who I was, and that I had a fair acquaintance with North American Indians myself, to say nothing of other various aborigines; at that he gave me a distant flabby hand, and condescended to ask me an uneasy question or two about my American travels. I told him I’d been out with Terry and Custer in ’76 – and that was as far as I got before he said: ‘Oh, indeed?’ down his nose, damned chilly, showed me his shoulder, and began the most infernal prose you ever heard to the rest of the company, all about the Yankees’ barbarous treatment of the Plains tribes after the Uprising, and their iniquitous Indian policy in general, the abominations of the reservation system, and the cruelties practised in the name of civilisation on helpless nomads who desired only to be left alone to pursue their traditional way of life as peaceful herdsmen, fostering their simple culture, honouring their ancient gods, and generally prancing about like fauns in Arcady. Mercifully, I hadn’t had dinner.

‘Noble savages, eh?’ says I, when he’d paused for breath, and he gave me a look full of sentimental spite.

‘I might call them that,’ snaps he. ‘Do I take it that you would disagree?’

‘Depends which ones you’re talking about,’ says I. ‘Now, Spotted Tail was a gentleman. Chico Velasquez, on the other hand, was an evil vicious brute. But you probably never met either of ’em. Care for a brandy, then?’

He went pink. ‘I thank you, no. By gentleman, I suppose,’ he went on, bristling, ‘you mean one who has despaired to the point of submission, while brute would no doubt describe any sturdy independent patriot who resisted the injustice of an alien rule, or revolted against broken treaties—’

‘If sturdy independence consists of cutting off women’s fingers and fringing your buckskins with them, then Chico was a patriot, no error,’ says I. ‘Mind you, that was the soft end of his behaviour. Hey, waiter, another one, and keep your thumb out of it, d’ye hear?’

My new acquaintance was going still pinker, and taking in breath; he wasn’t used to the argumentum ad Chico Velasquez, and it was plainly getting his goat, as I intended it should.

‘Barbarism is to be expected from a barbarian – especially when he has been provoked beyond endurance!’ He snorted and sneered. ‘Really, sir – will you seriously compare errant brutality committed by this … this Velasquez, as you call him – who by his name I take it sprang from that unhappy Pueblo stock who had been brutalised by centuries of Spanish atrocity – will you compare it, I say, with a calculated policy of suppression – nay, extermination – devised by a modern, Christian government? You talk of an Indian’s savagery? Yet you boast acquaintance with General Custer, and doubtless you have heard of Chivington? Sand Creek, sir! Wounded Knee! Washita! Ah, you see,’ cries he in triumph, ‘I can quote your own lexicon to you! In face of that, will you dare condone Washington’s treatment of the American Indian?’

‘I don’t condone it,’ says I, holding my temper. ‘And I don’t condemn it, either. It happened, just as the tide comes in, and since I saw it happen, I know better than to jump to the damnfool sentimental conclusions that are fashionable in college cloisters, let me tell you—’

There were cries of protest, and my anthropologist began to gobble. ‘Fashionable indeed! Have you read Mrs Jackson,1 sir? Are you ignorant of the miserable condition to which a proud and worthy people have been reduced? Since you served in the Sioux campaign, you cannot be unaware of the callous and vindictive zeal with which it and subsequent expeditions were conducted! Against a resistless foe! Can you defend the extirpation of the Modocs, or the Apaches, or a dozen others I could mention? For shame, sir!’ He was getting the bit between his teeth now, and I was warming just a trifle myself. ‘And all this at a time when the resources of a vast modern state might have been employed in a policy of humanity, restraint, and enlightenment! But no – all the dark old prejudices and hatreds must be given full and fearful rein, and the despised “hostile” annihilated or reduced to virtual serfdom.’ He gestured contemptuously. ‘And all you can say is that “it happened”. Tush, sir! So might Pilate have said: “It happened”.’ He was pleased with that, so he enlarged on it. ‘The Procurator of Judea would have made a fit aide-de-camp to your General Terry, I daresay. I wish you a very good night, General Flashman.’

Which would have enabled him to stalk off with the honours, but I don’t abandon an argument when reasoned persuasion may prevail.

‘Now see here, you mealy little pimp!’ says I. ‘I’ve had just about a bellyful of your pious hypocritical maundering. Take a look at this!’ And while he gobbled again, and his sycophants uttered shocked cries, I dropped my head and pulled apart my top hair for his inspection. ‘See that bald patch? That, my industrious researcher, was done by a Brulé scalping knife, in the hand of a peaceful herdsman, to a man who’d done his damnedest to see that the Brulés and everyone else in the Dacotah nation got a fair shake.’ Which was a gross exaggeration, but never mind that. ‘So much for humanity and restraint …’

‘Good God!’ cries he, blenching. ‘Very well, sir – you may flaunt a wound. It does not prove your case. Rather, it explains your partiality—’

‘It proves that at least I know what I’m talking about! Which is more than you can say. As to Custer, he’s receipted and filed for the idiot he was, and for Chivington, he was a murderous maniac, and what’s worse, an amateur. But if you think they were a whit more guilty than your darling redskins, you’re an even bigger bloody fool than you look. What bleating breast-beaters like you can’t comprehend,’ I went on at the top of my voice, while the toadies pawed at me and yapped for the porters, ‘is that when selfish frightened men – in other words, any men, red or white, civilised or savage – come face to face in the middle of a wilderness that both of ’em want, the Lord alone knows why, then war breaks out, and the weaker goes under. Policies don’t matter a spent piss – it’s the men in fear and rage and uncertainty watching the woods and skyline, d’you see, you purblind bookworm, you! And you burble about enlightenment, by God—’

‘Catch hold of his other arm, Fred!’ says the porter, heaving away. ‘Come along now, general, if you please.’

‘—try to enlighten a Cumanche war-party, why don’t you? Suggest humanity and restraint to the Jicarillas who carved up Mrs White and her baby on Rock Creek! Have you ever seen a Del Norte rancho after the Mimbrenos have left their calling cards? No, not you, you plush-bottomed bastard, you! All right, steward, I’m going, damn you … but let me tell you,’ I concluded, and I daresay I may have shaken my finger at the academic squirt, who had got behind a chair and was looking ready to bolt, ‘that I’ve a damned sight more use for the Indian than you have – as much as I have for the rest of humanity, at all events – and I don’t make ’em an excuse for parading my own virtue while not caring a fig for them, as you do, so there! I know your sort! Broken treaties, you vain blot – why, Chico Velasquez wouldn’t have recognised a treaty if he’d fallen over it in the dark …’ But by that time I was out in Pall Mall, addressing the vault of heaven.

‘Who the hell ever said the Washington government was Christian, anyway?’ I demanded, but the porter said he really couldn’t say, and did I want a cab?

You may wonder that I got in such a taking over one pompous windbag spouting claptrap; usually I just sit and sneer when the know-alls start prating on behalf of the poor oppressed heathen, sticking a barb in ’em as opportunity serves – why, I’ve absolutely heard ’em lauding the sepoy mutineers as honest patriots, and I haven’t even bothered to break wind by way of dissent. I know the heathen, and their oppressors, pretty well, you see, and the folly of sitting smug in judgement years after, stuffed with piety and ignorance and book-learned bias. Humanity is beastly and stupid, aye, and helpless, and there’s an end to it. And that’s as true for Crazy Horse as it was for Custer – and they’re both long gone, thank God. But I draw the line at the likes of my anthropological half-truther; oh, there’s a deal in what he says, right enough – but it’s only one side of the tale, and when I hear it puffed out with all that righteous certainty, as though every white man was a villain and every redskin a saint, and the fools swallow it and feel suitably guilty … well, it can get my goat, especially if I’ve got a drink in me and my kidneys are creaking. So I’m slung out of the Travellers’ for ungentlemanly conduct. Much I care; I wasn’t a member, anyway.

A waste of good passion, of course. The thing is, I suppose, that while I spent most of my time in the West skulking and running and praying to God I’d come out with a whole skin, I have a strange sentiment for the place, even now. That may surprise you, if you know my history – old Flashy, the decorated hero and cowardly venal scoundrel who never had a decent feeling in all his scandalous, lecherous life. Aye, but there’s a reason, as you shall see.

Besides, when you’ve seen the West almost from the beginning, as I did – trader, wagon-captain, bounty-hunter, irregular soldier, whoremaster, gambler, scout, Indian fighter (well, being armed in the presence of the enemy qualifies you, even if you don’t tarry long), and reluctant deputy marshal to J. B. Hickok, Esq., no less – you’re bound to retain an interest, even in your eighty-ninth year.2 And it takes just a little thing – a drift of woodsmoke, a certain sunset, the taste of maple syrup on a pancake, or a few words of Apache spoken unexpected – and I can see the wagons creaking down to the Arkansas crossing, and the piano stuck fast on a mudbank, with everyone laughing while Susie played ‘Banjo on my knee’ … Old Glory fluttering above the gate at Bent’s … the hideous zeep of Navajo war-arrows through canvas … the great bison herds in the distance spreading like oil on the yellow plain … the crash and stamp of fandango with the poblanas’ heels clicking and their silk skirts whirling above their knees … the bearded faces of Gallantin’s riders in the fire glow … the air like nectar when we rode in the spring from the high glory of Eagle Nest, up under the towering white peaks to Fort St Vrain and Laramie … the incredible stink of those dark dripping forms in the Apache sweatbath at Santa Rita … the great scarred Cheyenne braves with their slanting feathers, riding stately, like kings to council … the round firm flesh beneath my hands in the Gila forest, the sweet sullen lips whispering … ‘Make my bells ring again …’ oh, yes indeed, ma’am … and the nightmare – the screams and shots and war-whoops as Gall’s Hunkpapa horde came surging through the dust, and George Custer squatting on his heels, his cropped head in his hands as he coughed out his life, and the red-and-yellow devil’s face screaming at me from beneath the buffalo-scalp helmet as the hatchet drove down at my brow …

‘Well, boys, they killed me,’ as Wild Bill used to say – only it wasn’t permanent, and today I sit at home in Berkeley Square staring out at the trees beyond the railings in the rain, damning the cramp in my penhand and remembering where it all began, on a street in New Orleans in 1849, with your humble obedient trotting anxiously at the heels of John Charity Spring, MA, Oriel man, slaver, and homicidal lunatic, who was stamping his way down to the quay in a fury, jacket buttoned tight and hat jammed down, alternately blaspheming and quoting Horace …

‘I should have dropped you overboard off Finisterre!’ snarls he. ‘It would have been the price of you, by God! Aye, well, I missed my chance – quandoque bonus dormitat Homerus.’fn3 He wheeled on me suddenly, and those dreadful pale eyes would have frozen brandy. ‘But Homer won’t nod again, Mister Flashman, and you can lay to that. One false step out of you this trip, and you’ll wish the Amazons had got you!’

‘Captain,’ says I earnestly, ‘I’m as anxious to get out of this as you are – and you’ve said it yourself, how can I play you false?’

‘If I knew that I’d be as dirty a little Judas as you are.’ He considered me balefully. ‘The more I think of it, the more I like the notion of having those papers of Comber’s before we go a step farther.’

Now, those papers – which implicated both Spring himself and my miserly Scotch father-in-law up to their necks in the illegal slave trade – were the only card in my hand. Once Spring had them, he could drop me overboard indeed. Terrified as I was, I shook my head, and he showed his teeth in a sneering grin.

‘What are you scared of, you worm? I’ve said I’ll carry you home, and I keep my word. By God,’ he growled, and the scar on his brow started to swell crimson, a sure sign that he was preparing to howl at the moon, ‘will you dare say I don’t, you quaking offal? Will you? No, you’d better not! Why, you fool – I’ll have ’em within five minutes of your setting foot on my deck, in any event. Because you’re carrying them, aren’t you? You wouldn’t dare leave ’em out of your sight. I know you.’ He grinned again, nastily. ‘Omnia mea mecum portofn4 is your style. Where are they – in your coat-lining or under your boot-sole?’

It was no consolation that they were in neither, but sewn in the waistband of my pants. He had me, and if I didn’t want to be abandoned there and then to the mercy of the Yankee law – which was after me for murder, slave-stealing, impersonating a Naval officer, false pretences, theft of a wagon and horses, perjury, and issuing false bills of sale (Christ, just about everything except bigamy) – I had no choice but to fork out and hope to heaven he’d keep faith with me. He saw it in my face and sneered.

‘As I thought. You’re as easy to read as an open book – and a vile publication, too. We’ll have them now, if you please.’ He jerked his thumb at a tavern across the street. ‘Come on!’

‘Captain – for God’s sake let it wait till we’re aboard! The Yankee Navy traps’ll be scouring the town for me by now … please, Captain, I swear you’ll have ’em—’

‘Do as you’re damned well told!’ he rasped, and seizing my arm in an iron hand he almost ran me into the pub, and thrust me into a corner seat farthest from the bar; it was middling dim, with only one or two swells lounging at the tables, and a few of the merchant and trader sort talking at the bar, but just the kind of respectable ken that my legal and Navy acquaintances might frequent. I pointed this out, whining.

‘Five minutes more or less won’t hurt you,’ says Spring, ‘and they’ll satisfy me whether or not you’re breaking the habit of a lifetime by telling the truth for once.’ So while he bawled for juleps and kicked the black waiter for being dilatory – I wished to God he wouldn’t attract attention with his high table manners – I kept my back to the room and began surreptitiously picking stitches out of my flies with a penknife.

He drummed impatiently, growling, while I got the packet out – that precious sheaf of flimsy, closely written papers that Comber had died for – and he pawed through it, grinding his teeth as he read. ‘That ingrate sanctimonious reptile! He should have lingered for a year! I was like a father to the bastard, and see how he repaid my benevolence, by God – skulking and spying like a rat at a scuttle! But you’re all alike, you shabby-genteel vermin! Aye, Master Comber, Phaedrus limned your epitaph: saepe intereunt aliis meditantes necem,fn5 and serve the bastard right!’ He stuffed the papers into his pocket, drank, and brooded at me with that crazy glint in his eyes that I remembered so well from the Balliol College. ‘And you – you held on to them – why? To steer me into Execution Dock, you—’

‘Never!’ I protested. ‘Why, if I’d wanted to I could have done it back in the court – but I didn’t, did I?’

‘And put your own foul neck in a noose? Not you.’ He gave his barking laugh. ‘No … I’ll make a shrewd guess that you were keeping ’em to squeeze an income out of that Scotch miser Morrison – that was it, wasn’t it?’ Mad he might be, but his wits were sharp enough. ‘Filial piety, you leper! Well, if that was your game, you’re out of luck. He’s dead – and certainly damned. I had word from our New York agent three weeks ago. That takes you flat aback, doesn’t it, my bucko?’

And it did, but only for a moment. For if I couldn’t turn the screw on a corpse – well, I didn’t need to, did I? The little villain’s fortune would descend to his daughters, of whom my lovely simpleton wife Elspeth was the favourite – by George, I was rich! He’d been worth a cool two million, they reckoned, and at least a quarter would come to her, and me … unless the wily old skinflint had cooked up some legal flummery to keep my paws off it, as he’d done these ten years past. But he couldn’t – Elspeth must inherit, and I could twist her round my little finger … couldn’t I? She’d always doted on me, although I had a suspicion that she sampled the marriage mutton elsewhere when my back was turned – I couldn’t be sure, though, and anyway, an occasional unwifely romp was no great matter, while she’d been dependent on Papa. But now, when she was rolling in blunt, she might be off whoring with all hands and the cook, and too much of that might well damp her ardour for an absent husband. Who could say how she would greet the returning Odysseus, now that she was filthy rich and spoiled for choice? That apart, if I knew my fair feather-brain, she’d be spending the dibs – my dibs – like a drunk duke on his birthday. The sooner I was home the better – but Morrison kicking the bucket was capital news, just the same.

Spring was watching me as he watched the weather, shrewd and sour, and knowing what a stickler he could be for proper form, murderous pirate though he was, I tried to put on a solemn front, and muttered about this unexpected blow, shocking calamity, irreplaceable loss, and all the rest of it.

‘I can see that,’ he scoffed. ‘Stricken with grief, I daresay. I know the signs – a face like a Tyneside winter and a damned inheriting gleam in your eye. Bah, why don’t you blubber, you hypocritical pup? Nulli jactantius moerent, quam qui loetantur,fn6 or to give Tacitus a free translation, you’re reckoning up the bloody dollars already! Well, you haven’t got ’em yet, cully, and if you want to see London Bridge again—’ and he bared his teeth at me ‘—you’ll tread mighty delicate, like Agag, and keep on the weather side of John Charity Spring.’

‘What d’you mean? I’ve given you the papers – you’re bound to see me safe –’

‘Oh, I’ll do that, never fear.’ There was a cunning shift in those awful empty eyes. ‘Me duce tutus eris,fn7 and d’ye know why? Because when you reach England, and you and the rest of Morrison’s carrion brood have got your claws on his fortune, you’ll discover that you need an experienced director for his extensive maritime concerns – lawful and otherwise.’ He grinned at me triumphantly. ‘You’ll pay through the nose for him, too, but you’ll be getting a safe, scholarly man of affairs, who’ll not only manage a fleet, but can be trusted to see that no indiscreet inquiries are ever directed at your recent American activities, or the fact that your signature as supercargo is to be found on the articles of a slave trader—’

‘Christ, look who’s talking!’ I exclaimed. ‘I was shanghaied, kidnapped – and what about you—’

‘Damn your eyes, will you take that tone with me?’ he roared, and a few heads at the nearest table turned, so he dropped his voice to its normal snarl. ‘English law holds no terrors for me; I’ll be in Brest or Calais, taking my money in francs and guilders. Thanks to those misbegotten scum of ushers at Oxford, who cast me into the gutter out of spite, who robbed me of dignity and the fruits of scholarship …’ His scar was crimsoning again, as it always did when Oxford was mentioned; Oriel had kicked him out, you see, no doubt for purloining the College plate or strangling the Dean, but he always claimed it was academic jealousy. He writhed and growled and settled down. ‘England holds nothing for me now. But your whole future lies there – and there’ll be damned little future if the truth about this past year comes out. The Army? Disgrace. Your newfound fortune? Ruin. You might even swing,’ says he, smacking his lips. ‘And your lady wife would certainly find the social entrée more difficult to come by. On which score,’ he added malevolently, ‘I wonder how she would take the news that her husband is a whoremongering rake who covered everything that moved aboard the Balliol College. By and large, mutual discretion will be in both our interests, don’t you think?’

And the evil lunatic grinned at me sardonically and drained his glass. ‘We’ll have leisure to discuss business on the voyage home – and to resume your classical education, whose interruption by those meddling Yankee Navy bastards I’m sure you deplore as much as I do. Hiatus valde deflendus,fn8 as I seem to remember telling you before. Now get that drink into you and we’ll be off.’

As I’ve said, he was really mad. If he thought he could blackmail me with his ridiculous threats – and him a discredited don turned pirate who’d be clapped into Bedlam as soon as he opened his mouth in civilised company – he was well out of court. But I knew better than to say so, just then; raving or not, he was my one hope of getting out of that beastly country. And if I had to endure his interminable proses about Horace and Ovid all across the Atlantic, so be it; I drank up meekly, pushed back my chair, turned to the room – and walked slap into a nightmare.

It was the most ordinary, trivial thing, and it changed the course of my life, as such things do. Perhaps it killed Custer; I don’t know. As I took my first step from the table a tall man standing at the bar roared with laughter, and stepped back, just catching me with his shoulder. Another instant and I’d have been past him, unseen – but he jostled me, and turned to apologise.

‘Your pardon, suh,’ says he, and then his eyes met mine, and stared, and for full three seconds we stood frozen in mutual recognition. For I knew that face: the coarse whiskers, the scarred cheek, the prominent nose and chin, and the close-set eyes. I knew it before I remembered his name: Peter Omohundro.