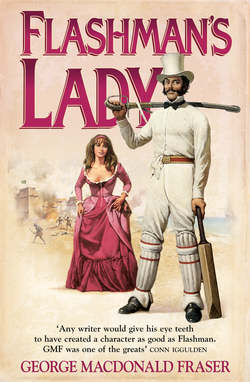

Читать книгу Flashman’s Lady - George Fraser MacDonald - Страница 11

ОглавлениеSo they’re talking about amending the leg-before-wicket rule again. I don’t know why they bother, for they’ll never get it right until they go back to the old law which said that if you put your leg in front of the ball a-purpose to stop it hitting the stumps, you were out, and d----d good riddance to you. That was plain enough, you’d have thought, but no; those mutton-brains in the Marylebone club have to scratch their heads over it every few years, and gas for days on end about the line of delivery and the point of pitch, and the L--d knows what other rubbish, and in the end they cross out a word and add another, and the whole thing’s as incomprehensible as it was before. Set of doddering old women.

It all comes of these pads that batters wear nowadays. When I was playing cricket we had nothing to guard our precious shins except our trousers, and if you were fool enough to get your ankle in the way of one of Alfie Mynn’s shooters, why, it didn’t matter whether you were in front of the wicket or sitting on the pavilion privy – you were off to get your leg in plaster, no error. But now they shuffle about the crease like yokels in gaiters, and that great muffin Grace bleats like a ruptured choirboy if a fast ball comes near him. Wouldn’t I just have liked to get him on the old Lord’s wicket after a dry summer, with the pitch rock-hard, Mynn sending down his trimmers from one end and myself going all-out at t’other – they wouldn’t have been calling him the ‘Champion’ then, I may tell you; the old b-----’s beard would have been snow-white after two overs. And the same goes for that fat black nawab and the pup Fry, too.

From this you may gather that I was a bowler myself, not a batter, and if I say I was a d----d good one, well, the old scores are there to back me up. Seven for 32 against the Gentlemen of Kent, five for 12 against the England XI, and a fair number of runs as a tail-end slogger to boot. Not that I prided myself on my batting; as I’ve said, it could be a risky business against fast men in the old days, when wickets were rough, and I may tell you privately that I took care never to face up to a really scorching bowler without woollen scarves wrapped round my legs (under my flannels) and an old tin soup-bowl over my essentials; sport’s all very well, but you mustn’t let it incapacitate you for the manliest game of all. No, just let me go in about number eight or nine, when the slow lobbers and twisters were practising their wiles, and I could slash away in safety, and then, when t’other side had their innings – give me that ball and a thirty-pace run-up and just watch me make ’em dance.

It may strike you that old Flashy’s approach to our great summer game wasn’t quite that of your school-storybook hero, apple-cheeked and manly, playing up unselfishly for the honour of the side and love of his gallant captain, revelling in the jolly rivalry of bat and ball while his carefree laughter rings across the green sward. No, not exactly; personal glory and cheap wickets however you could get ’em, and d--n the honour of the side, that was my style, with a few quid picked up in side-bets, and plenty of skirt-chasing afterwards among the sporting ladies who used to ogle us big hairy fielders over their parasols at Canterbury Week. That’s the spirit that wins matches, and you may take my word for it, and ponder our recent disastrous showing against the Australians while you’re about it.1

Of course, I speak as one who learned his cricket in the golden age, when I was a miserable fag at Rugby, toadying my way up the school and trying to keep a whole skin in that infernal jungle – you took your choice of emerging a physical wreck or a moral one, and I’m glad to say I never hesitated, which is why I’m the man I am today, what’s left of me. I snivelled and bought my way to safety when I was a small boy, and bullied and tyrannised when I was a big one; how the d---l I’m not in the House of Lords by now, I can’t think. That’s by the way; the point is that Rugby taught me only two things really well, survival and cricket, for I saw even at the tender age of eleven that while bribery, fawning, and deceit might ensure the former, they weren’t enough to earn a popular reputation, which is a very necessary thing. For that, you had to shine at games, and cricket was the only one for me.

Not that I cared for it above half, at first, but the other great sport was football, and that was downright dangerous; I rubbed along at it only by limping up late to the scrimmages yelping: ‘Play up, you fellows, do! Oh, confound this game leg of mine!’ and by developing a knack of missing my charges against bigger men by a fraction of an inch, plunging on the turf just too late with heroic gasps and roarings.2 Cricket was peace and tranquillity by comparison, without any danger of being hacked in the members – and I turned out to be uncommon good at it.

I say this in all modesty; as you may know, I have three other prime talents, for horses, languages, and fornication, but they’re all God-given, and no credit that I can claim. But I worked to make myself a cricketer, d----d hard I worked, which is probably why, when I look back nowadays on the rewards and trophies of an eventful life – the medals, the knighthood, the accumulated cash, the military glory, the drowsy, satisfied women – all in all, there’s not much I’m prouder of than those five wickets for 12 runs against the flower of England’s batters, or that one glorious over at Lord’s in ’42 when – but I’ll come to that in a moment, for it’s where my present story really begins.

I suppose, if Fuller Pilch had got his bat down just a split second sooner, it would all have turned out different. The Skrang pirates wouldn’t have been burned out of their h--lish nest, the black queen of Madagascar would have had one lover fewer (not that she’d have missed a mere one, I daresay, the insatiable great b---h), the French and British wouldn’t have bombarded Tamitave, and I’d have been spared kidnapping, slavery, blowpipes, and the risk of death and torture in unimaginable places – aye, old Fuller’s got a lot to answer for, God rest him. However, that’s anticipating – I was telling you how I became a fast bowler at Rugby, which is a necessary preliminary.

It was in the ’thirties, you see, that round-arm bowling came into its own, and fellows like Mynn got their hands up shoulder-high. It changed the game like nothing since, for we saw what fast bowling could be – and it was fast – you talk about Spofforth and Brown, but none of them kicked up the dust like those early trimmers. Why, I’ve seen Mynn bowl to five slips and three long-stops, and his deliveries going over ’em all, first bounce right down to Lord’s gate. That’s my ticket, thinks I, and I took up the new slinging style, at first because it was capital fun to buzz the ball round the ears of rabbits and funks who couldn’t hit back, but I soon found this didn’t answer against serious batters, who pulled and drove me all over the place. So I mended my ways until I could whip my fastest ball onto a crown piece, four times out of five, and as I grew tall I became faster still, and was in a fair way to being Cock of Big Side – until that memorable afternoon when the puritan prig Arnold took exception to my being carried home sodden drunk, and turfed me out of the school. Two weeks before the Marylebone match, if you please – well, they lost it without me, which shows that while piety and sobriety may ensure you eternal life, they ain’t enough to beat the MCC.

However, that was an end to my cricket for a few summers, for I was packed off to the Army and Afghanistan, where I shuddered my way through the Kabul retreat, winning undeserved but undying fame in the siege of Jallalabad. All of which I’ve related elsewhere;fn1 sufficient to say that I bilked, funked, ran for dear life and screamed for mercy as occasion demanded, all through that ghastly campaign, and came out with four medals, the thanks of Parliament, an audience of our Queen, and a handshake from the Duke of Wellington. It’s astonishing what you can make out of a bad business if you play your hand right and look noble at the proper time.

Anyway, I came home a popular hero in the late summer of ’42, to a rapturous reception from the public and my beautiful idiot wife Elspeth. Being lionised and fêted, and making up for lost time by whoring and carousing to excess, I didn’t have much time in the first few months for lighter diversions, but it chanced that I was promenading down Regent Street one afternoon, twirling my cane with my hat on three hairs and seeking what I might devour, when I found myself outside ‘The Green Man’. I paused, idly – and that moment’s hesitation launched me on what was perhaps the strangest adventure of my life.

It’s long gone now, but in those days ‘The Green Man’ was a famous haunt of cricketers, and it was the sight of bats and stumps and other paraphernalia of the game in the window that suddenly brought back memories, and awoke a strange hunger – not to play, you understand, but just to smell the atmosphere again, and hear the talk of batters and bowlers, and the jargon and gossip. So I turned in, ordered a plate of tripe and a quart of home-brewed, exchanged a word or two with the jolly pipe-smokers in the tap, and was soon so carried away by the homely fare, the cheery talk and laughter, and the clean hearty air of the place, that I found myself wishing I’d gone on to the Haymarket and got myself a dish of hot spiced trollop instead. Still, there was time before supper, and I was just calling the waiter to settle up when I noticed a fellow staring at me across the room. He met my eye, shoved his chair back, and came over.

‘I say,’ says he, ‘aren’t you Flashman?’ He said it almost warily, as though he didn’t wish quite to believe it. I was used to this sort of thing by now, and having fellows fawn and admire the hero of Jallalabad, but this chap didn’t look like a toad-eater. He was as tall as I was, brown-faced and square-chinned, with a keen look about him, as though he couldn’t wait to have a cold tub and a ten-mile walk. A Christian, I shouldn’t wonder, and no smoking the day before a match.

So I said, fairly cool, that I was Flashman, and what was it to him.

‘You haven’t changed,’ says he, grinning. ‘You won’t remember me, though, do you?’

‘Any good reason why I should try?’ says I. ‘Here, waiter!’

‘No, thank’ee,’ says this fellow. ‘I’ve had my pint for the day. Never take more during the season.’ And he sat himself down, cool as be-d----d, at my table.

‘Well, I’m relieved to hear it,’ says I, rising. ‘You’ll forgive me, but—’

‘Hold on,’ says he, laughing. ‘I’m Brown. Tom Brown – of Rugby. Don’t say you’ve forgotten!’

Well, in fact, I had. Nowadays his name is emblazoned on my memory, and has been ever since Hughes published his infernal book in the ’fifties, but that was still in the future, and for the life of me I couldn’t place him. Didn’t want to, either; he had that manly, open-air reek about him that I can’t stomach, what with his tweed jacket (I’ll bet he’d rubbed down his horse with it) and sporting cap; not my style at all.

‘You roasted me over the common-room fire once,’ says he, amiably, and then I knew him fast enough, and measured the distance to the door. That’s the trouble with these snivelling little sneaks one knocks about at school; they grow up into hulking louts who box, and are always in prime trim. Fortunately this one appeared to be Christian as well as muscular, having swallowed Arnold’s lunatic doctrine of love-thine-enemy, for as I hastily muttered that I hoped it hadn’t done him any lasting injury, he laughed heartily and clapped me on the shoulder.

‘Why, that’s ancient history,’ cries he. ‘Boys will be boys, what? Besides, d’ye know – I feel almost that I owe you an apology. Yes,’ and he scratched his head and looked sheepish. ‘Tell the truth,’ went on this amazing oaf, ‘when we were youngsters I didn’t care for you above half, Flashman. Well, you treated us fags pretty raw, you know – of course, I guess it was just thoughtlessness, but, well, we thought you no end of a cad, and – and … a coward, too.’ He stirred uncomfortably, and I wondered was he going to fart. ‘Well, you caught us out there, didn’t you?’ says he, meeting my eye again. ‘I mean, all this business in Afghanistan … the way you defended the old flag … that sort of thing. By George,’ and he absolutely had tears in his eyes, ‘it was the most splendid thing … and to think that you … well, I never heard of anything so heroic in my life, and I just wanted to apologize, old fellow, for thinking ill of you – ’cos I’ll own that I did, once – and ask to shake your hand, if you’ll let me.’

He sat there, with his great paw stuck out, looking misty and noble, virtue just oozing out of him, while I marvelled. The strange thing is, his precious pal Scud East, whom I’d hammered just as generously at school, said almost the same thing to me years later, when we met as prisoners in Russia – confessed how he’d loathed me, but how my heroic conduct had wiped away all old scores, and so forth. I wonder still if they believed that it did, or if they were being hypocrites for form’s sake, or if they truly felt guilty for once having harboured evil thoughts of me? D----d if I know; the Victorian conscience is beyond me, thank G-d. I know that if anyone who’d done me a bad turn later turned out to be the Archangel Gabriel, I’d still hate the b----d; but then, I’m a scoundrel, you see, with no proper feelings. However, I was so relieved to find that this stalwart lout was prepared to let bygones be bygones that I turned on all my Flashy charms, pumped his fin heartily, and insisted that he break his rule for once, and have a glass with me.

‘Well, I will, thank’ee,’ says he, and when the beer had come and we’d drunk to dear old Rugby (sincerely, no doubt, on his part) he puts down his mug and says:

‘There’s another thing – matter of fact it was the first thought that popped into my head when I saw you just now – I don’t know how you’d feel about it, though – I mean, perhaps your wounds ain’t better yet?’

He hesitated. ‘Fire away,’ says I, thinking perhaps he wanted to introduce me to his sister.

‘Well, you won’t have heard, but my last half at school, when I was captain, we had no end of a match against the Marylebone men – lost on first innings, but only nine runs in it, and we’d have beat ’em, given one more over. Anyway, old Aislabie – you remember him? – was so taken with our play that he has asked me if I’d like to get up a side, Rugby past and present, for a match against Kent. Well, I’ve got some useful hands – you know young Brooke, and Raggles – and I remembered you were a famous bowler, so … What d’ye say to turning out for us – if you’re fit, of course?’

It took me clean aback, and my tongue being what it is, I found myself saying: ‘Why, d’you think you’ll draw a bigger gate with the hero of Afghanistan playing?’

‘Eh? Good lord, no!’ He coloured and then laughed. ‘What a cynic you are, Flashy! D’ye know,’ says he, looking knowing, ‘I’m beginning to understand you, I think. Even at school, you always said the smart, cutting things that got under people’s skins – almost as though you were going out of your way to have ’em think ill of you. It’s a contrary thing – all at odds with the truth, isn’t it? Oh, aye,’ says he, smiling owlishly, ‘Afghanistan proved that, all right. The German doctors are doing a lot of work on it – the perversity of human nature, excellence bent on destroying itself, the heroic soul fearing its own fall from grace, and trying to anticipate it. Interesting.’ He shook his fat head solemnly. ‘I’m thinking of reading philosophy at Oxford this term, you know. However, I mustn’t prose. What about it, old fellow?’ And d--n his impudence, he slapped me on the knee. ‘Will you bowl your expresses for us – at Lord’s?’

I’d been about to tell him to take his offer along with his rotten foreign sermonising and drop ’em both in the Serpentine, but that last word stopped me. Lord’s – I’d never played there, but what cricketer who ever breathed wouldn’t jump at the chance? You may think it small enough beer compared with the games I’d been playing lately, but I’ll confess it made my heart leap. I was still young and impressionable then and I almost knocked his hand off, accepting. He gave me another of his thunderous shoulder-claps (they pawed each other something d--nable, those hearty young champions of my youth) and said, capital, it was settled then.

‘You’ll want to get in some practice, no doubt,’ says he, and promptly delivered a lecture about how he kept himself in condition, with runs and exercises and forgoing tuck, just as he had at school. From that he harked back to the dear old days, and how he’d gone for a weep and a pray at Arnold’s tomb the previous month (our revered mentor having kicked the bucket earlier in the year, and not before time, in my opinion). Excited as I was at the prospect of the Lord’s game, I’d had about my bellyful of Master Pious Brown by the time he was done, and as we took our leave of each other in Regent Street, I couldn’t resist the temptation to puncture his confounded smugness.

‘Can’t say how glad I am to have seen you again, old lad,’ says he, as we shook hands. ‘Delighted to know you’ll turn out for us, of course, but, you know, the best thing of all has been – meeting the new Flashman, if you know what I mean. It’s odd,’ and he fixed his thumbs in his belt and squinted wisely at me, like an owl in labour, ‘but it reminds me of what the Doctor used to say at confirmation class – about man being born again – only it’s happened to you – for me, if you understand me. At all events, I’m a better man now, I feel, than I was an hour ago. God bless you, old chap,’ says he, as I disengaged my hand before he could drag me to my knees for a quick prayer and a chorus of ‘Let us with a gladsome mind’. He asked which way I was bound.

‘Oh, down towards Haymarket,’ says I. ‘Get some exercise, I think.’

‘Capital,’ says he. ‘Nothing like a good walk.’

‘Well … I was thinking more of riding, don’t you know.’

‘In Haymarket?’ He frowned. ‘No stables thereaway, surely?’

‘Best in town,’ says I. ‘A few English mounts, but mostly French fillies. Riding silks black and scarlet, splendid exercise, but d----d exhausting. Care to try it?’

For a moment he was all at a loss, and then as understanding dawned he went scarlet and white by turns, until I thought he would faint. ‘My G-d,’ he whispered hoarsely. I tapped him on the weskit with my cane, all confidential.

‘You remember Stumps Harrowell, the shoemaker, at Rugby, and what enormous calves he had?’ I winked while he gaped at me. ‘Well, there’s a German wench down there whose poonts are even bigger. Just about your weight; do you a power of good.’

He made gargling noises while I watched him with huge enjoyment.

‘So much for the new Flashman, eh?’ says I. ‘Wish you hadn’t invited me to play with your pure-minded little friends? Well, it’s too late, young Tom; you’ve shaken hands on it, haven’t you?’

He pulled himself together and took a breath. ‘You may play if you wish,’ says he. ‘More fool I for asking you – but if you were the man I had hoped you were, you would—’

‘Cry off gracefully – and save you from the pollution of my company? No, no, my boy – I’ll be there, and just as fit as you are. But I’ll wager I enjoy my training more.’

‘Flashman,’ cries he, as I turned away, ‘don’t go to – to that place, I beseech you. It ain’t worthy—’

‘How would you know?’ says I. ‘See you at Lord’s.’ And I left him full of Christian anguish at the sight of the hardened sinner going down to the Pit. The best of it was, he was probably as full of holy torment at the thought of my foul fornications as he would have been if he’d galloped that German tart himself; that’s unselfishness for you. But she’d have been wasted on him, anyway.

However, just because I’d punctured holy Tom’s daydreams, don’t imagine that I took my training lightly. Even while the German wench was recovering her breath afterwards and ringing for refreshments, I was limbering up on the rug, trying out my old round-arm swing; I even got some of her sisters in to throw oranges to me for catching practice, and you never saw anything jollier than those painted dollymops scampering about in their corsets, shying fruit. We made such a row that the other customers put their heads out, and it turned into an impromptu innings on the landing, whores versus patrons (I must set down the rules for brothel cricket some day, if I can recall them; cover point took on a meaning that you won’t find in ‘Wisden’, I know). The whole thing got out of hand, of course, with furniture smashed and the sluts shrieking and weeping, and the madame’s bullies put me out for upsetting her disorderly house, which seemed a trifle hard.

Next day, though, I got down to it in earnest, with a ball in the garden. To my delight none of my old skill seemed to have deserted me, the thigh which I’d broken in Afghanistan never even twinged, and I crowned my practice by smashing the morning-room window while my father-in-law was finishing his breakfast; he’d been reading about the Rebecca Riots3 over his porridge, it seemed, and since he’d spent his miserable life squeezing and sweating his millworkers, and had a fearful guilty conscience according, his first reaction to the shattering glass was that the starving mob had risen at last and were coming to give him his just deserts.

‘Ye d----d Goth!’ he spluttered, fishing the fragments out of his whiskers. ‘Ye don’t care who ye maim or murder; I micht ha’e been killed! Have ye nae work tae go tae?’ And he whined on about ill-conditioned loafers who squandered their time and his money in selfish pleasure, while I nuzzled Elspeth good morning over her coffee service, marvelling as I regarded her golden-haired radiance and peach-soft skin that I had wasted strength on that suety frau the evening before, when this had been waiting between the covers at home.

‘A fine family ye married intae,’ says her charming sire. ‘The son stramashin’ aboot destroyin’ property while the feyther’s lyin’ abovestairs stupefied wi’ drink. Is there nae mair toast?’

‘Well, it’s our property and our drink,’ says I, helping myself to kidneys. ‘Our toast, too, if it comes to that.’

‘Aye, is’t, though, my buckie?’ says he, looking more like a spiteful goblin than ever. ‘And who peys for’t? No’ you an’ yer wastrel parent. Aye, an’ ye can keep yer sullen sniffs to yersel’, my lassie,’ he went on to Elspeth. ‘We’ll hae things aboveboard, plump an’ plain. It’s John Morrison foots the bills, wi’ good Scots siller, hard-earned, for this fine husband o’ yours an’ the upkeep o’ his hoose an’ family; jist mind that.’ He crumpled up his paper, which was sodden with spilled coffee. ‘Tach! There my breakfast sp’iled for me. “Our property” an’ “our drink”, ye say? Grand airs and patched breeks!’ And out he strode, to return in a moment, snarling. ‘And since you’re meant tae be managin’ this establishment, my girl, ye’ll see tae it that we hae marmalade after this, and no’ this d----d French jam! Con-fee – toor! Huh! Sticky rubbish!’ And he slammed the door behind him.

‘Oh, dear,’ sighs Elspeth. ‘Papa is in his black mood. What a shame you broke the window, dearest.’

‘Papa is a confounded blot,’ says I, wolfing kidneys. ‘But now that we’re rid of him, give us a kiss.’

You’ll understand that we were an unusual menage. I had married Elspeth perforce, two years before when I had the ill-fortune to be stationed in Scotland, and had been detected tupping her in the bushes – it had been the altar or pistols for two with her fire-eating uncle. Then, when my drunken guv’nor had gone smash over railway shares, old Morrison had found himself saddled with the upkeep of the Flashman establishment, which he’d had to assume for his daughter’s sake.

A pretty state, you’ll allow, for the little miser wouldn’t give me or the guv’nor a penny direct, but doled it out to Elspeth, on whom I had to rely for spending money. Not that she wasn’t generous, for in addition to being a stunning beauty she was also as brainless as a feather mop, and doted on me – or at least, she seemed to, but I was beginning to have my doubts. She had a hearty appetite for the two-backed game, and the suspicion was growing on me that in my absence she’d been rolling the linen with any chap who’d come handy, and was still spreading her favours now that I was home. As I say, I couldn’t be sure – for that matter, I’m still not, sixty years later. The trouble was and is, I dearly loved her in my way, and not only lustfully – although she was all you could wish as a night-cap – and however much I might stallion about the town and elsewhere, there was never another woman that I cared for besides her. Not even Lola Montez, or Lakshmibai, or Lily Langtry, or Ko Dali’s daughter, or Duchess Irma, or Takes-Away-Clouds-Woman, or Valentina, or … or, oh, take your choice, there wasn’t one to come up to Elspeth.

For one thing, she was the happiest creature in the world, and pitifully easy to please; she revelled in the London life, which was a rare change from the cemetery she’d been brought up in – Paisley, they call it – and with her looks, my new-won laurels, and (best of all) her father’s shekels, we were well-received everywhere, her ‘trade’ origins being conveniently forgotten. (There’s no such thing as an unfashionable hero or an unsuitable heiress.) This was just nuts to Elspeth, for she was an unconscionable little snob, and when I told her I was to play at Lord’s, before the smartest of the sporting set, she went into raptures – here was a fresh excuse for new hats and dresses, and preening herself before the society rabble, she thought. Being Scotch, and knowing nothing, she supposed cricket was a gentleman’s game, you see; sure enough, a certain level of the polite world followed it, but they weren’t precisely the high cream, in those days – country barons, racing knights, well-to-do gentry, maybe a mad bishop or two, but pretty rustic. It wasn’t quite as respectable as it is now.

One reason for this was that it was still a betting game, and the stakes could run pretty high – I’ve known £50,000 riding on a single innings, with wild side-bets of anything from a guinea to a thou. on how many wickets Marsden would take, or how many catches would fall to the slips, or whether Pilch would reach fifty (which he probably would). With so much cash about, you may believe that some of the underhand work that went on would have made a Hays City stud school look like old maid’s loo – matches were sold and thrown, players were bribed and threatened, wickets were doctored (I’ve known the whole eleven of a respected county side to sneak out en masse and p--s on the wicket in the dark, so that their twisters could get a grip next morning; I caught a nasty cold myself). Of course, corruption wasn’t general, or even common, but it happened in those good old sporting days – and whatever the purists may say, there was a life and stingo about cricket then that you don’t get now.

It looked so different, even; if I close my eyes I can see Lord’s as it was then, and I know that when the memories of bed and battle have lost their colours and faded to misty grey, that at least will be as bright as ever. The coaches and carriages packed in the road outside the gate, the fashionable crowd streaming in by Jimmy Dark’s house under the trees, the girls like so many gaudy butterflies in their summer dresses and hats, shaded by parasols, and the men guiding ’em to chairs, some in tall hats and coats, others in striped weskits and caps, the gentry uncomfortably buttoned up and the roughs and townies in shirt-sleeves and billycocks with their watch-chains and cutties; the bookies with their stands outside the pavilion, calling the odds, the flash chaps in their mighty whiskers and ornamented vests, the touts and runners and swell mobsmen slipping through the press like ferrets, the pot-boys from the Lord’s pub thrusting along with trays loaded with beer and lemonade, crying ‘Way, order, gents! Way, order!’; old John Gully, the retired pug, standing like a great oak tree, feet planted wide, smiling his gentle smile as he talked to Alfred Mynn, whose scarlet waist-scarf and straw boater were a magnet for the eyes of the hero-worshipping youngsters, jostling at a respectful distance from these giants of the sporting world; the grooms pushing a way for some doddering old Duke, passing through nodding and tipping his tile, with his poule-of-the-moment arm-in-arm, she painted and bold-eyed and defiant as the ladies turned the other way with a rustle of skirts; the bowling green and archery range going full swing, with the thunk of the shafts mingling with the distant pomping of the artillery band, the chatter and yelling of the vendors, the grind of coach-wheels and the warm hum of summer ebbing across the great green field where Stevie Slatter’s boys were herding away the sheep and warning off the bob-a-game players; the crowds ten-deep at the nets to see Pilch at batting practice, or Felix, agile as his animal namesake, bowling those slow lobs that seemed to hang forever in the air.

Or I see it in the late evening sun, the players in their white top-hats trooping in from the field, with the ripple of applause running round the ropes, and the urchins streaming across to worship, while the old buffers outside the pavilion clap and cry ‘Played, well played!’ and raise their tankards, and the Captain tosses the ball to some round-eyed small boy who’ll guard it as a relic for life, and the scorer climbs stiffly down from his eyrie and the shadows lengthen across the idyllic scene, the very picture of merry, sporting old England, with the umpires bundling up the stumps, the birds calling in the tall trees, the gentle evenfall stealing over the ground and the pavilion, and the empty benches, and the willow wood-pile behind the sheep pen where Flashy is plunging away on top of the landlord’s daughter in the long grass. Aye, cricket was cricket then.

Barring the last bit, which took place on another joyous occasion, that’s absolutely what it was like on the afternoon when the Gentlemen of Rugby, including your humble servant, went out to play the cracks of Kent (twenty to one on, and no takers). At first I thought it was going to be a frost, for while most of my team-mates were pretty civil – as you’d expect, to the Hector of Afghanistan – the egregious Brown was decidedly cool, and so was Brooke, who’d been head of the school in my time and was the apple of Arnold’s eye – that tells you all you need to know about him; he was clean-limbed and handsome and went to church and had no impure thoughts and was kind to animals and old ladies and was a midshipman in the Navy; what happened to him I’ve no idea, but I hope he absconded with the ship’s funds and the admiral’s wife and set up a knocking-shop in Valparaiso. He and Brown talked in low voices in the pavilion, and glanced towards me; rejoicing, no doubt, over the sinner who hadn’t repented.

Then it was time to play, and Brown won the toss and elected to bat, which meant that I spent the next hour beside Elspeth’s chair, trying to hush her imbecile observations on the game, and waiting for my turn to go in. It was a while coming, because either Kent were going easy to make a game of it, or Brooke and Brown were better than you’d think, for they survived the opening whirlwind of Mynn’s attack, and when the twisters came on, began to push the score along quite handsomely. I’ll say that for Brown, he could play a deuced straight bat, and Brooke was a hitter. They put on thirty for the first wicket, and our other batters were game, so that we had seventy up before the tail was reached, and I took my leave of my fair one, who embarrassed me d--nably by assuring her neighbours that I was sure to make a score, because I was so strong and clever. I hastened to the pavilion, collared a pint of ale from the pot-boy, and hadn’t had time to do more than blow off the froth when there were two more wickets down, and Brown says: ‘In you go, Flashman.’

So I picked up a bat from beside the flagstaff, threaded my way through the crowd who turned to look curiously at the next man in, and stepped out on to the turf – you must have done it yourselves often enough, and remember the silence as you walk out to the wicket, so far away, and perhaps there’s a stray handclap, or a cry of ‘Go it, old fellow!’, and no more than a few spectators loafing round the ropes, and the fielding side sit or lounge about, stretching in the sun, barely glancing at you as you come in. I knew it well enough, but as I stepped over the ropes I happened to glance up – and Lord’s truly smote me for the first time. Round the great emerald field, smooth as a pool table, there was this mighty mass of people, ten deep at the boundary, and behind them the coaches were banked solid, wheel to wheel, crowded with ladies and gentlemen, the whole huge multitude hushed and expectant while the sun caught the glittering eyes of thousands of opera-glasses and binocles glaring at me – it was d----d unnerving, with that vast space to be walked across, and my bladder suddenly holding a bushel, and I wished I could scurry back into the friendly warm throng behind me.

You may think it odd that nervous funk should grip me just then; after all, my native cowardice has been whetted on some real worthwhile horrors – Zulu impis and Cossack cavalry and Sioux riders, all intent on rearranging my circulatory and nervous systems in their various ways; but there were others to share the limelight with me then, and it’s a different kind of fear, anyway. The minor ordeals can be d----d scaring simply because you know you’re going to survive them.

It didn’t last above a second, while I gulped and hesitated and strode on, and then the most astounding thing happened. A murmur passed along the banks of people, and then it grew to a roar, and suddenly it exploded in the most deafening cheering you ever heard; you could feel the shock of it rolling across the ground, and ladies were standing up and fluttering their handkerchiefs and parasols, and the men were roaring hurrah and waving their hats, and jumping up on the carriages, and in the middle of it all the brass band began to thump out ‘Rule, Britannia’, and I realized they weren’t cheering the next man in, but saluting the hero of Jallalabad, and I was fairly knocked sideways by the surprise of it all. However, I fancy I played it pretty well, raising my white topper right and left while the music and cheering pounded on, and hurrying to get to the wicket as a modest hero should. And here was slim little Felix, in his classroom whiskers and charity boy’s cap, smiling shyly and holding out his hand – Felix, the greatest gentleman bat in the world, mark you, leading me to the wicket and calling for three cheers from the Kent team. And then the silence fell, and my bat thumped uncommon loud as I hit it into the blockhole, and the fielders crouched, and I thought, oh G-d, this is the serious business, and I’m bound to lay an egg on the scorer, I know I am, and after such a welcome, too, and with my bowels quailing I looked up the wicket at Alfred Mynn.

He was a huge man at the best of times, six feet odd and close on twenty stone, with a face like fried ham garnished with a double helping of black whisker, but now he looked like Goliath, and if you think a man can’t tower above you from twenty-five yards off, you ain’t seen young Alfie. He was smiling, idly tossing up the ball which looked no bigger than a cherry in his massive fist, working one foot on the turf – pawing it, bigod. Old Aislabie gave me guard, quavered ‘Play!’ I gripped my bat, and Mynn took six quick steps and swung his arm.

I saw the ball in his hand, at shoulder height, and then something fizzed beside my right knee, I prepared to lift my bat – and the wicket-keeper was tossing the ball to Felix at point. I swallowed in horror, for I swear I never saw the d----d thing go, and someone in the crowd cries, ‘Well let alone, sir!’ There was a little puff of dust settling about four feet in front of me; that’s where he pitches, thinks I, oh J---s, don’t let him hit me! Felix, crouching facing me, barely ten feet away, edged just a little closer, his eyes fixed on my feet; Mynn had the ball again, and again came the six little steps, and I was lunging forward, eyes tight shut, to get my bat down where the dust had jumped last time. I grounded it, my bat leaped as something hit it a hammer blow, numbing my wrists, and I opened my eyes to see the ball scuttling off to leg behind the wicket. Brooke yells ‘Come on!’, and the lord knows I wanted to, but my legs didn’t answer, and Brooke had to turn back, shaking his head.

This has got to stop, thinks I, for I’ll be maimed for life if I stay here. And panic, mingled with hate and rage, gripped me as Mynn turned again; he strode up to the wicket, arm swinging back, and I came out of my ground in a huge despairing leap, swinging my bat for dear life – there was a sickening crack and in an instant of elation I knew I’d caught it low down on the outside edge, full swipe, the b----y thing must be in Wiltshire by now, five runs for certain, and I was about to tear up the pitch when I saw Brooke was standing his ground, and Felix, who’d been fielding almost in my pocket, was idly tossing the ball up in his left hand, shaking his head and smiling at me.

How he’d caught it only he and Satan know; it must have been like snatching a bullet from the muzzle. But he hadn’t turned a hair, and I could only trudge back to the pavilion, while the mob groaned in sympathy, and I waved my bat to them and tipped my tile – after all I was a bowler, and at least I’d taken a swing at it. And I’d faced three balls from Alfred Mynn.

We closed our hand at 91, Flashy caught Felix, nought, and it was held to be a very fair score, although Kent were sure to pass it easily, and since it was a single-hand match that would be that. In spite of my blank score – how I wished I had gone for that single off the second ball! – I was well received round the pavilion, for it was known who I was by now, and several gentlemen came to shake my hand, while the ladies eyed my stalwart frame and simpered to each other behind their parasols; Elspeth was glowing at the splendid figure I had cut in her eyes, but indignant that I had been out when my wicket hadn’t been knocked down, because wasn’t that the object of the game? I explained that I had been caught out, and she said it was a most unfair advantage, and that little man in the cap must be a great sneak, at which the gentlemen around roared with laughter and ogled her, calling for soda punch for the lady and swearing she must be taken on to the committee to amend the rules.

I contented myself with a glass of beer before we went out to field, for I wanted to be fit to bowl, but d---e if Brown didn’t leave me loafing in the outfield, no doubt to remind me that I was a whoremonger and therefore not fit to take an over. I didn’t mind, but lounged about pretty nonchalant, chatting with the townies near the ropes, and shrugging my shoulders eloquently when Felix or his partner made a good hit, which they did every other ball. They fairly knocked our fellows all over the wicket, and had fifty up well within the hour; I observed to the townies that what we wanted was a bit of ginger, and limbered my arm, and they cheered and began to cry: ‘Bring on the Flash chap! Huzza for Afghanistan!’ and so forth, which was very gratifying.

I’d been getting my share of attention from the ladies in the carriages near my look-out, and indeed had been so intent on winking and swaggering that I’d missed a long hit, at which Brown called pretty sharply to me to mind out; now one or two of the more spirited ladybirds began to echo the townies, who egged them on, so that ‘Bring on the Flash chap!’ began to echo round the ground, in gruff bass and piping soprano. Finally Brown could stand it no longer, and waved me in, and the mob cheered like anything, and Felix smiled his quiet smile and took fresh guard.

On the whole he treated my first over with respect, for he took only eleven off it, which was better than I deserved. For of course I flung my deliveries down with terrific energy, the first one full pitch at his head, and the next three horribly short, in sheer nervous excitement. The crowd loved it, and so did Felix, curse him; he didn’t reach the first one, but he drew the second beautifully for four, cut the third on tiptoe, and swept the last right off his upper lip and into the coaches near the pavilion.

How the crowd laughed and cheered, while Brown bit his lip with vexation, and Brooke frowned his disgust. But they couldn’t take me off after only one turn; I saw Felix say something to his partner, and the other laughed – and as I walked back to my look-out a thought crept into my head, and I scowled horribly and clapped my hands in disgust, at which the spectators yelled louder than ever. ‘Give ’em the Afghan pepper, Flashy!’ cries one, and ‘Run out the guns!’ hollers another; I waved my fist and stuck my hat on the back of my head, and they cheered and laughed again.

They gave a huge shout when Brown called me up for my second turn, and settled themselves to enjoy more fun and fury. You’ll get it, my boys, thinks I, as I thundered up to the wicket, with the mob counting each step, and my first ball smote about half way down the pitch, flew high over the batsman’s head, and they ran three byes. That brought Felix to face me again, and I walked back, closing my ears to the shouting and to Brown’s muttered rebuke. I turned, and just from the lift of Felix’s shoulders I could see he was getting set to knock me into the trees; I fixed my eye on the spot dead in line with his off stump – he was a left-hander, which left the wicket wide as a barn door to my round delivery – and ran up determined to bowl the finest, fastest ball of my life.

And so I did. Very well, I told you I was a good bowler, and that was the best ball I ever delivered, which is to say it was unplayable. I had dropped the first one short on purpose, just to confirm what everyone supposed from the first over – that I was a wild chucker, with no more head than flat beer. But the second had every fibre directed at that spot, with just a trifle less strength than I could muster, to keep it steady, and from the moment it left my hand Felix was gone. Granted I was lucky, for the spot must have been bald; it was a shooter, skidding in past his toes when he expected it round his ears, and before he could smother it his stump was cart-wheeling away.

The yell that went up split the heaven, and he walked past me shaking his head and shooting me a quizzy look while the fellows slapped my back, and even Brooke condescended to cry ‘Well bowled!’ I took it very offhand, but inside I was thinking: ‘Felix! Felix, by G-d!’ – I’d not have swapped that wicket for a peerage. Then I was brought back to earth, for the crowd were cheering the new man in, and I picked up the ball and turned to face the tall, angular figure with the long-reaching arms and the short-handled bat.

I’d seen Fuller Pilch play at Norwich when I was a young shaver, when he beat Marsden of Yorkshire for the single-wicket championship of England; so far as I ever had a boyhood hero, it was Pilch, the best professional of his day – some say of any day, although it’s my belief this new boy Rhodes may be as good. Well, Flash, thinks I, you’ve nothing to lose, so here goes at him.

Now, what I’d done to Felix was head bowling, but what came next was luck, and nothing else. I can’t account for it yet, but it happened, and this is how it was. I did my d----dest to repeat my great effort, but even faster this time, and in consequence I was just short of a length; whether Pilch was surprised by the speed, or the fact that the ball kicked higher than it had any right to do, I don’t know, but he was an instant slow in reaching forward, which was his great shot. He didn’t ground his bat in time, the ball came high off the blade, and I fairly hurled myself down the pitch, all arms and legs, grabbing at a catch I could have held in my mouth. I nearly muffed it, too, but it stuck between finger and thumb, and the next I knew they were pounding me on the back, and the townies were in full voice, while Pilch turned away slapping his bat in vexation. ‘B----y gravel!’ cries he. ‘Hasn’t Dark got any brooms, then?’ He may have been right, for all I know.

By now, as you may imagine, I was past caring. Felix – and Pilch. There was nothing more left in the world just then, or so I thought; what could excel those twin glorious strokes? My grandchildren will never believe this, thinks I, supposing I have any – by George, I’ll buy every copy of the sporting press for the next month, and paper old Morrison’s bedroom with ’em. And yet the best was still to come.

Mynn was striding to the crease; I can see him now, and it brings back to me a line that Macaulay wrote in that very year: ‘And now the cry is “Aster”! and lo, the ranks divide, as the great Lord of Luna comes on with stately stride.’ That was Alfred the Great to a ‘t’, stately and magnificent, with his broad crimson sash and the bat like a kid’s paddle in his hand; he gave me a great grin as he walked by, took guard, glanced leisurely round the field, tipped his straw hat back on his head, and nodded to the umpire, old Aislabie, who was shaking with excitement as he called ‘Play!’

Well, I had no hope at all of improving on what I’d done, you may be sure, but I was determined to bowl my best, and it was only as I turned that it crossed my mind – old Aislabie’s a Rugby man, and it was out of pride in the old school that he arranged this fixture; honest as God, to be sure, but like all enthusiasts he’ll see what he wants to see, won’t he? – and Mynn’s so tarnation big you can’t help hitting him somewhere if you put your mind to it, and bowl your fastest. It was all taking shape even as I ran up to the wicket: I’d got Felix by skill, Pilch by luck, and I’d get Mynn by knavery or perish in the attempt. I fairly flung myself up to the crease, and let go a perfect snorter, dead on a length but a good foot wide of the leg stump. It bucked, Mynn stepped quickly across to let it go by, it flicked his calf, and by that time I was bounding across Aislabie’s line of sight, three feet off the ground, turning as I sprang and yelling at the top of my voice: ‘How was he there, sir?’

Now, a bowler who’s also a Gentleman of Rugby don’t appeal unless he believes it; that gooseberry-eyed old fool Aislabie hadn’t seen a d----d thing with me capering between him and the scene of the crime, but he concluded there must be something in it, as I knew he would, and by the time he had fixed his watery gaze, Mynn, who had stepped across, was plumb before the stumps. And Aislabie would have been more than human if he had resisted the temptation to give the word that everyone in that ground except Alfie wanted to hear. ‘Out!’ cries he. ‘Yes, out, absolutely! Out! Out!’

It was bedlam after that; the spectators went wild, and my team-mates simply seized me and rolled me on the ground; the cheering was deafening, and even Brown pumped me by the hand and slapped me on the shoulder, yelling ‘Bowled, oh, well bowled, Flashy!’ (You see the moral: cover every strumpet in London if you’ve a mind to, it don’t signify so long as you can take wickets.) Mynn went walking by, shaking his head and cocking an eyebrow in Aislabie’s direction – he knew it was a crab decision, but he beamed all over his big red face like the sporting ass he was, and then did something which has passed into the language: he took off his boater, presented it to me with a bow, and says:

‘That trick’s worth a new hat any day, youngster.’

(I’m d----d if I know which trick he meant,4 and I don’t much care; I just know the leg-before-wicket rule is a perfectly splendid one, if they’ll only let it alone.)

After that, of course, there was only one thing left to do. I told Brown that I’d sprained my arm with my exertions – brought back the rheumatism contracted from exposure in Afghanistan, very likely … horrid shame … just when I was finding a length … too bad … worst of luck … field all right, though … (I wasn’t going to run the risk of having the other Kent men paste me all over the ground, not for anything). So I went back to the deep field, to a tumultuous ovation from the gallery, which I acknowledged modestly with a tip of Mynn’s hat, and basked in my glory for the rest of the match, which we lost by four wickets. (If only that splendid chap Flashman had been able to go on bowling, eh? Kent would have been knocked all to smash in no time. They do say he has a jezzail bullet in his right arm still – no it ain’t, it was a spear thrust – I tell you I read it in the papers, etc., etc.)

It was beer all round in the pavilion afterwards, with all manner of congratulations – Felix shook my hand again, ducking his head in that shy way of his, and Mynn asked was I to be home next year, for if the Army didn’t find a use for me, he could, in the casual side which he would get together for the Grand Cricket Week at Canterbury. This was flattery on the grand scale, but I’m not sure that the sincerest tribute I got wasn’t Fuller Pilch’s knitted brows and steady glare as he sat on a bench with his tankard, looking me up and down for a full two minutes and never saying a word.

Even the doddering Duke came up to compliment me and say that my style reminded him absolutely of his own – ‘Did I not remark it to you, my dear?’ says he to his languid tart, who was fidgeting with her parasol and stifling a yawn while showing me her handsome profile and weighing me out of the corner of her eye. ‘Did I not observe that Mr Flashman’s shooter was just like the one I bowled out Beauclerk with at Maidstone in ’06? – directed to his off stump, sir, caught him goin’ back, you understand pitched just short, broke and shot, middle stump, bowled all over his wicket – ha! ha! what?’

I had to steady the old fool before he tumbled over demonstrating his action, and his houri, assisting, took the opportunity to rub a plump arm against me. ‘No doubt we shall have the pleasure of seeing you at Canterbury next summer, Mr Flashman,’ she murmurs, and the old pantaloon cries aye, aye, capital notion, as she helped him away; I made a note to look her up then, since she’d probably have killed him in the course of the winter.

It wasn’t till I was towelling myself in the bathhouse, and getting outside a brandy punch, that I realized I hadn’t seen Elspeth since the match ended, which was odd, since she’d hardly miss a chance to bask in my reflected glory. I dressed and looked about; no sign of her among the thinning crowd, or outside the pavilion, or at the ladies’ tea tables, or at our carriage; coachee hadn’t seen her either. There was a fairish throng outside the pub, but she’d hardly be there, and then someone plucked my sleeve, and I turned to find a large, beery-faced individual with black button eyes at my elbow.

‘Mr Flashman, sir, best respex,’ says he, and tapped his low-crown hat with his cudgel. ‘You’ll forgive the liberty, I’m sure – Tighe’s the monicker, Daedalus Tighe, ev’yone knows me, agent an’ accountant to the gentry—’ and he pushed a card in my direction between sweaty fingers. ‘Takin’ the hoppor-toonity, my dear sir an’ sportsman, of presentin’ my compliments an’ best vishes, an’—’

‘Thank’ee,’ says I, ‘but I’ve no bets to place.’

‘My dear sir!’ says he, beaming. ‘The werry last idea!’ And he invited his cronies, a seedy-flash bunch, to bear him witness. ‘My makin’ so bold, dear sir, was to inwite you to share my good fortun’, seein’ as ’ow you’ve con-tribooted so ’andsome to same – namely, an’ first, by partakin’ o’ some o’ this ’ere French jam-pain – poodle’s p--s to some, but as drunk in the bes’ hestablishments by the werriest swells such as – your good self, sir. Wincent,’ says he, ‘pour a glass for the gallant—’

‘Another time,’ says I, giving him my shoulder, but the brute had the effrontery to catch my arm.

‘’Old on, sir!’ cries he. ‘’Arf a mo’, that’s on’y the sociable pree-liminary. I’m vishful to present to your noble self the—’

‘Go to the d---l!’ snaps I. He stank of brandy.

‘—sum of fifty jemmy o’ goblins, as an earnest o’ my profound gratitood an’ respeck. Wincent!’

And d----d if the weasel at his elbow wasn’t thrusting a glass of champagne at me with one hand and a fistful of bills in the other. I stopped short, staring.

‘What the deuce …?’

‘A triflin’ token of my hes-teem,’ says Tighe. He swayed a little, leering at me, and for all the reek of booze, the flash cut of his coat, the watch-chain over his flowery silk vest, and the gaudy bloom in his lapel – the marks of the vulgar sport, in fact – the little eyes in his fat cheeks were as hard as coals. ‘You vun it for me, my dear sir – an’ plenty to spare, d---e. Didn’t ’e, though?’ His confederates, crowding round, chortled and raised their glasses. ‘By the sweat – yore pardon, sir – by the peerspyration o’ yore brow – an’ that good right arm, vot sent back Felix, Pilch, an’ Alfred Mynn in three deliveries, sir. Look ’ere,’ and he snapped a finger to Vincent, who dropped the glass to whip open a leather satchel at his waist – it was stuffed with notes and coin.

‘You, sir, earned that. You did, though. Ven you put avay Fuller Pilch – an’, veren’t that a ’andsome catch, now? – I sez to Fat Bob Napper, vot reckons e’s king o’ the odds an’ evens – “Napper,” sez I, “that’s a ’ead bowler, that is. Vot d’ye give me ’e don’t put out Mynn, first ball?” “Gammon,” sez ’e. “Three in a row – never! Thahsand to one, an’ you can pay me now.” Generous odds, sir, you’ll allow.’ And the rascal winked and tapped his nose. ‘So – hon goes my quid – an’ ’ere’s Napper’s thahsand, cash dahn, give ’im that – an’ fifty on it’s yore’s, my gallant sir, vith the grateful compliments of Daedalus Tighe, Hesk-wire, agent an’ accountant to the gentry, ’oo ’ereby salutes’ – and he raised his glass and belched unsteadily – ‘yore ’onner’s pardon, b----r them pickles – ’oo salutes the most wicious right harm in the noble game o’ cricket today! Hip-hip-hip – hooray!’

I couldn’t help being amused at the brute, and his pack of rascals – drunken bookies and touts on the spree, and too far gone to appreciate their own impudence.

‘My thanks for the thought, Mr Tighe,’ says I, for it don’t harm to be civil to a bookie, and I was feeling easy, ‘you may drink my health with it.’ And I pushed firmly past him, at which he staggered and sat down heavily in a froth of cheap champagne, while his pals hooted and weaved in to help him. Not that I couldn’t have used the fifty quid, but you can’t be seen associating with cads of that kidney, much less accepting their gelt. I strode on, with cries of ‘Good luck, sir!’ and ‘Here’s to the Flash cove!’ following me. I was still grinning as I resumed my search for Elspeth, but as I turned into the archery range for a look there, the smile was wiped off my lips – for there were only two people in the long alley between the hedges: the tall figure of a man, and Elspeth in his arms.

I came to a dead halt, silent – for three reasons. First, I was astonished. Secondly, he was a big, vigorous brute, by what I could see of him – which was a massive pair of shoulders in a handsomely cut broadcloth (no expense spared there), and thirdly, it passed quickly through my mind that Elspeth, apart from being my wife, was also my source of supply. Food for thought, you see, but before I had even an instant to taste it, they both turned their heads and I saw that Elspeth was in the act of stringing a shaft to a ladies’ bow – giggling and making a most appealing hash of it – while her escort, standing close in behind her, was guiding her hands, which of course necessitated putting his arms about her, with her head against his shoulder.

All very innocent – as who knows better than I, who’ve taken advantage of many such situations for an ardent squeeze and fondle?

‘Why, Harry,’ cries she, ‘where have you been all this while? See, Don Solomon is teaching me archery – and I have been making the sorriest show!’ Which she demonstrated by fumbling the shaft, swinging her bow arm wildly, and letting fly into the hedge, squeaking with delighted alarm. ‘Oh, I am quite hopeless, Don Solomon, unless you hold my hands!’

‘The fault is mine, dear Mrs Flashman,’ says he, easily. He managed to keep an arm round her, while bowing in my direction. ‘But here is Mars, who I’m sure is a much better instructor for Diana than I could ever be.’ He smiled and raised his hat. ‘Servant, Mr Flashman.’

I nodded, pretty cool, and looked down my nose at him, which wasn’t easy, since he was all of my height, and twice as big around – portly, you might say, if not fat, with a fleshy, smiling face, and fine teeth which flashed white against his swarthy skin. Dago, for certain, perhaps even Oriental, for his hair and whiskers were blue-black and curly, and as he came towards me he was moving with that mincing Latin grace, for all his flesh. A swell, too, by the elegant cut of his togs; diamond pin in his neckercher, a couple of rings on his big brown hands – and, by Jove, even a tiny gold ring in one ear. Part-nigger, not a doubt of it, and with all a rich nigger’s side, too.

‘Oh, Harry, we have had such fun!’ cries Elspeth, and my heart gave a little jump as I looked at her. The gold ringlets under her ridiculous bonnet, the perfect pink and white complexion, the sheer innocent beauty of her as she sparkled with laughter and reached out a hand to me. ‘Don Solomon has shown me bowling, and how to shoot – ever so badly! – and entertained me – for the cricket came so dull when you were not playing, with those tedious Kentish people popping away, and—’

‘Hey?’ says I, astonished. ‘You mean you didn’t see me bowl?’

‘Why, no, Harry, but we had the jolliest time among the side-shows, with ices and hoop-la …’ She prattled on, while the greaser raised his brows, smiling from one to the other of us.

‘Dear me,’ says he, ‘I fear I have lured you from your duty, dear Mrs Flashman. Forgive me,’ he went on to me, ‘for I have the advantage of you still. Don Solomon Haslam, to command,’ and he nodded and flicked his handkerchief. ‘Mr Speedicut, who I believe is your friend, presented me to your so charming lady, and I took the liberty of suggesting that we … take a stroll. If I had known you were to be put on – but tell me … any luck, eh?’

‘Oh, not too bad,’ says I, inwardly furious that while I’d been performing prodigies Elspeth had been fluttering at this oily flammer. ‘Felix, Pilch and Mynn, in three balls – if you call it luck. Now, my dear, if Mr Solomon will excuse—’

To my amazement he burst into laughter. ‘I would call it luck!’ cries he. ‘That would be a daydream, to be sure! I’d settle for just one of ’em!’

‘Well, I didn’t,’ says I, glaring at him. ‘I bowled Felix, caught out Pilch, and had Mynn leg before – which probably don’t mean much to a foreigner—’

‘Good G-d!’ cries he. ‘You don’t mean it! You’re bamming us, surely?’

‘Now, look’ee, whoever you are—’

‘But – but – oh, my G-d!’ He was fairly spluttering, and suddenly he seized my hand, and began pumping it, his face alight. ‘My dear chap – I can’t believe it! All three? And to think I missed it!’ He shook his head, and burst out laughing again. ‘Oh, what a dilemma! How can I regret an hour spent with the loveliest girl in London – but, oh, Mrs Flashman, what you’ve cost me! Why, there’s never been anything like it! And to think that we were missing it all! Well, well, I’ve paid for my susceptibility to beauty, to be sure! Well done, my dear chap, well done! But this calls for celebration!’

I was fairly taken aback at this, while Elspeth looked charmingly bewildered, but nothing must do but he bore us off to where the liquor was, and demanded of me, action by action, a description of how I’d bowled out the mighty three. I’ve never seen a man so excited, and I’ll own I found myself warming to him; he clapped me on the shoulder, and slapped his knee with delight when I’d done.

‘Well, I’m blessed! Why, Mrs Flashman, your husband ain’t just a hero – he’s a prodigy!’ At which Elspeth glowed and squeezed my hand, which banished the last of my temper. ‘Felix, Pilch, and Mynn! Extraordinary. Well – I thought I was something of a cricketer, in my humble way – I played at Eton, you know – we never had a match with Rugby, alas! but I fancy I’d be a year or two before your time, anyway, old fellow. But this quite beats everything!’

It was fairly amusing, not least for the effect it was having on Elspeth. Here was this gaudy foreign buck, who’d come spooning round her, d----d little flirt that she was, and now all his attention was for my cricket. She was between exulting on my behalf and pouting at being overlooked, but when we parted from the fellow, with fulsome compliments and assurances that we must meet again soon, on his side, and fair affability on mine, he won her heart by kissing her hand as though he’d like to eat it. I didn’t mind, by now; he seemed not a bad sort, for a ’breed, and if he’d been to Eton he was presumably half-respectable, and obviously rolling in rhino. All men slobbered over Elspeth, anyway.

So the great day ended, which I’ll never forget for its own splendid sake: Felix, Pilch, and Mynn, and those three ear-splitting yells from the mob as each one fell. It was a day that held the seed of great events, too, as you’ll see, and the first tiny fruit was waiting for us when we got back to Mayfair. It was a packet handed in at the door, and addressed to me, enclosing bills for fifty pounds, and a badly printed note saying ‘With the compliments of D. Tighe, Esq.’ Of all the infernal impudence; that b----y bookie, or whatever he was, having the starch to send cash to me, as though I were some pro. to be tipped.

I’d have kicked his backside to Whitechapel and back, or taken a cane to him for his presumption, if he’d been on hand. Since he wasn’t, I pocketed the bills and burned his letter; it’s the only way to put these upstarts in their place.

* * *

[Extract from the diary of Mrs H. Flashman, undated, 1842]

… to be sure, it was very natural of H. to pay some attention to the other ladies at Lord’s, for they were so forward in their admiration of him – and am I to blame you, less fortunate sisters? He looked so tall and proud and handsome, like the splendid English Lion that he is, that I felt quite faint with love and pride … to think that this striking man, the envy and admiration of all, is – my husband!! He is perfection, and I love him more than I can tell.

Still, I could wish that he had been a little less attentive to those ladies near us, who smiled and waved to him when he was in the field, and some even so far forgot the obligations of modesty upon our tender sex, as to call out to him! Of course, it is difficult for him to appear indifferent, so Admired as he is – and he has such an unaffected, gallant nature, and feels, I know, that he must acknowledge their flatteries, for fear that he should be thought lacking in that easy courtesy which becomes a gentleman. He is so Generous and Considerate, even to such déclassé persons as that odious Mrs Leo Lade, the Duke’s companion, whose admiration of H. was so open and shameless that it caused some remark, and made me blush for her reputation – which to be sure, she hadn’t any!!! But H.’s simple, boyish goodness can see no fault in anyone – not even such an abandoned female as I’m sure she is, for they say … but I will not sully your fair page, dear diary, with such a Paltry Thing as Mrs Leo.

Yet mention of her reminds me yet again of my Duty to Protect my dear one – for he is still such a boy, with all a boy’s naiveté and high spirit. Why, today, he looked quite piqued and furious at the attention shown to me by Don S.H., who is quite sans reproche and the most distinguished of persons. He has over fifty thousand a year, it is said, from estates and revenues in the Far East Indies, and is on terms with the Best in Society, and has been received by H.M. He is entirely English, although his mother was a Spanish Donna, I believe, and is of the most engaging manners and address, and the jolliest person besides. I confess I was not a little amused to find how I captivated him, which is quite harmless and natural, for I have noticed that Gentlemen of his Complexion are even more ardent in their addresses to the fair than those of Pure European Blood. Poor H. was not well pleased, I fear, but I could not help thinking it would do him no harm to be made aware that both sexes are wont to indulge in harmless gallantries, and if he is to be admired by such as Mrs L.L., he cannot object to the Don’s natural regard for me. And to be sure, they are not to be compared, for Don S.H.’s addresses are of the utmost discretion and niceness; he is amusing, with propriety, engaging without familiarity. No doubt we shall see much of him in Society this winter, but not so much, I promise, as will make my Dear Hero too jealous – he has such sensibility …

[End of extract – G. de R.]