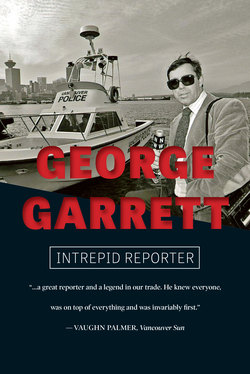

Читать книгу George Garrett - George Garrett - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 5

My Career Moves On

ОглавлениеAnnouncers who begin their careers in small-market radio stations can hardly wait to move to a larger market. They routinely send out audition tapes to bigger stations in the hope that the program director will listen to the tapes and consider hiring them. I was just like any ambitious kid lucky enough to get into radio.

Long before I had any plans to marry Joan or work at CKNW in Vancouver, and after a successful start at CJNB North Battleford, a small-market station, I wanted to try for a bigger market. My ambition, after about a year at CJNB, was to get a job at my hometown station, CHAB Moose Jaw. It was a popular station with a large audience through southern Saskatchewan, particularly farm families. It was folksy radio with such programs as The Mailbag every afternoon. A popular personality was a guy named Dick Lillico who hosted a morning program in which he played soft music and read poetry. Dick was habitually late arriving for his 8:30 a.m. start time. The theme song was soft music with birds singing in the background. Halfway through the theme, Lillico would burst through the control door and hand a few records to the operator, then run to the studio. By the time he got there the theme would almost be over, requiring the operator to gently fade down the music, move the needle to the start of the record and begin playing it again. Then he would open Lillico’s mike. Lillico was so smooth that listeners would never know he had been in such a rush. Lillico and personality Bob Giles mounted their own comedy road show, playing in towns throughout the listening area. Farm audiences shrieked with laughter at one skit in which six-foot-four Giles would appear in a baby diaper.

CHAB had attracted some very good broadcasters. Sports announcer Art Henderson was so knowledgeable about baseball and other sports that he could ad lib an entire sportscast after just a few minutes of looking at results from the teletype or a recent newspaper. As a kid of about fifteen, before I got any work in radio, I had hung around CHAB, standing in the hallway outside the main studio watching Henderson flawlessly report the sports. Beyond the studio was the control room where the operator worked the controls and did some announcing. My heart ached to be the guy behind the glass. Only a few years later, that dream came true and I was hired by CHAB.

At CHAB I was a board announcer operating for other announcers and doing some programs of my own. I was quickly put out on the street one morning to cover a major story. An airliner owned by what was then called Trans-Canada Air Lines (later Air Canada) collided in midair with an RCAF training plane. Both plunged to the ground, scattering wreckage over the north area of the city. Everyone aboard both planes was killed. Part of my story involved going to a makeshift morgue in the armoury. I stepped carefully around the bodies of the victims covered with blankets. It was a sobering experience and very difficult for a young person with no experience in news to describe and create a story for listeners.

I was given another assignment on a Saturday evening to go to the local train station to interview someone on the then hot topic of Crowsnest Pass freight rates, which western farmers considered discriminatory. For one thing, it meant that it was cheaper to ship goods east to west than the other way around. I used the station car to do the interview even though the railway station was only a few blocks from the radio station. When I finished the interview and recorded a story I got the bright idea that I could use the station car to drive to Regina, sixty-four kilometres to the east, to visit the guy who had given me my first job at CJNB North Battleford, Tommy Nelson. He had moved to Regina.

We had a nice visit but I stayed a little too late. It was a very stormy night; in fact, it was a blizzard. I found I could see the blacktop highway better if I drove with my lights off. At one point, I happened to glance at the gas gauge and realized in a panic that I was about to run out of gas. I had no alternative but to stop at a farmhouse near the highway, wake the poor farmer and ask for some gas. Obligingly, he put gas in the car from an elevated tank in the yard. It was purple gas that was supposed to be used for farm equipment, purple to show it was exempt from road tax. It was illegal to use it in passenger cars. I made it back to the radio station, but it was now after 7:00 a.m. I parked the car and went in to say hello to our morning man, Jay Leddy. “Have you got the station car?” he demanded. Apparently, the assistant manager, Ned Skingle, had arrived early and wanted to know who had the car. I was in big trouble. Later in the morning I was called up to the office of program director Bob Giles. “George,” he said, “the station car is for station business. Got it?” “Yes, Bob,” I said contritely, and that was the end of it.

Or so I thought. The story went around the station like wildfire. The next day, chief engineer Merv Pickford was installing a direct phone line to the transmitter and asked operators like me where I would like him to place the handset near the control panel. Chief announcer George Price chirped, “George would like to have you install it in the station car.”

Price was a consummate professional. His diction was perfect, his presentation very smooth. He had a habit of reading all his news copy over carefully, then taking a smoke break before going on the air. On one occasion he put the copy down on the lid of a tape recorder and went out for his cigarette. When he returned about two minutes before airtime, he discovered his whole newscast was missing. Paul Hack, a sports guy, had grabbed the tape recorder, put the lid on it without removing the news copy and left on assignment. When Price discovered what happened he desperately called downstairs to the newsroom and said, “My whole newscast is gone. Grab me any copy you can—anything—and rush it up to me.” Price went on the air exactly on time and amazingly ad libbed the first three or four stories from memory. In my nearly fifty years in radio, I never met anyone who could have done that.

That newscast was truly an innovative idea created by program director Bob Giles. The concept was to compartmentalize a radio newscast in the same format as Time magazine with segments for international, national and local news and politics, science, entertainment, sports and weather. It was a half-hour package and was extraordinarily well done.

My first newscast on CHAB was a ten-minute major newscast at 10:00 p.m. I read it over carefully, rehearsed it and went on the air, nervous as a cat. Although I had had a year’s experience at CJNB North Battleford, this was different. CHAB had a number of very experienced announcers whom I had admired and respected for years. Now I would be working alongside them. I was intimidated but it turned out I need not have worried. The first phone call after that 10 p.m. newscast came from a guy whose voice I recognized instantly. It was one of our outstanding announcers with a great voice—Joe Lawlor. He introduced himself and said, “That was a fine newscast, George. Good job!” I was so pleased I could have burst with pride.

My interest in news was just beginning. As a kid wanting to get into radio, I had wanted to be a disc jockey. I was now realizing there was more substance to news. Giles eventually moved me into doing the major half-hour news package at 6:00 p.m., the one based on the Time magazine format, and I did quite well with it.

Then Bob Giles left CHAB and moved to CKNW, then located in New Westminster, BC. He invited me to come visit him on my summer holiday, and I drove to the West Coast with my brother, Bob, his wife, Myrt, and their young son, Robbie. When I visited Giles at CKNW one of the first things he said was, “So when do you want to come to CKNW?” I was floored. I was far too inexperienced to come to such a big station but Giles told me to apply to program director Hal Davis. I was barely twenty years old and CKNW was not in the habit of hiring people that young. But to my amazement, I was offered a job at $300 a month. I’ll never know why I had the audacity to say I needed $350, but Davis said, “Sorry, $300—absolute tops!” I accepted. It was sometime later that I learned that Davis had hired me largely on Bob Giles’s recommendation. I have always been deeply indebted to both of them. Both have passed away. Each made a great contribution to radio and to my career.

Although I had been a disc jockey and general announcer in the first four years of my career, I gradually began taking an interest in news coverage, particularly when I was assigned to the 6:00 p.m. news program at CHAB Moose Jaw in 1953 with the Time magazine format. When I moved to CKNW Vancouver in 1956, I became a full-time newsman for the first time in my career. It was the beginning of a fantastic journey.