Читать книгу Nine Dragons - George Herman - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

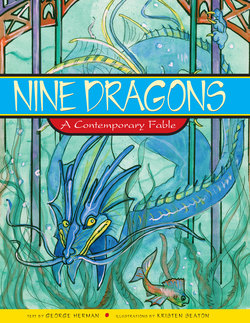

ОглавлениеThe village of Wongsu was built on rich and fertile earth

by people from the Ancient Land to the east.

Flat and wet, it was good for growing rice, and it was encircled

by a wall of mountains where wild game ran.

No one could remember who first saw this valley and settled here

or what was beyond the high mountains,

but generations of Wongsu had been farmers and hunters in this blessed valley,

and they fed their children with the gifts of the earth and the deep woods.

The village of Makai, on the opposite side of the mountains,

was founded by people who came many years after the Wongsu.

They arrived from the west, from beyond the Wide Water, in great canoes of wood and fiber.

Their skins were sun-bronzed and, for the most part, they were a carefree people.

They fed their children with the gifts of the deep sea:

the fish mantled in many colors,

the clicking, clawing crab, the snapping lobster,

and the sweet grasses of the deep.

They also harvested the fruit of trees and vines:

the tasty fig, the hard-shelled coconut, the bright banana, the prickly pineapple, and the pear.

Separating the two villages were the massive mountains.

The people of Makai and the people of Wongsu

never climbed these rocky, shadowy towers

because they were too busy with their work —

and because — well — they were afraid.

There were times when the mountains seemed to spit flames

as they spiraled glowing ashes against the dark sky.

Because of this, but unknown to each other,

the Wongsu and the Makai shared a common legend:

that the mountains were the home of terrible and terrifying dragons

who came to the island before them, flying high above the storm that brought with it the great flood,

and who were now the last of their kind.

And like all legends,

there was some truth in this.

Deep in the dark and mysterious mountains there were, indeed, nine dragons —

nine creatures of wings and claws and scales.

When annoyed — which was often —

they would show their white teeth — as sharp as angry words —

and they would breathe fire into the night sky.

Their scent was as foul as swamp air, their wings were like leather,

and their scales glistened and gleamed like robes made of a thousand jewels.

Most of their kind had died in the flood

or were killed by adventurers

who mistook them for wicked creatures

because they were different from them.

So now only these nine remained,

comfortable but aging,

in the hundred arms of a great cave,

feeding on wild goats and bears that dared to wander too near them.

Now it happened that one year the Goddess of Rain did not weep

as she usually did at the passing of the springtime,

and the mountain streams that would feed the valley rice fields

instead slipped quietly into the thirsting earth or drifted away into the clouded sky.

The rhythm of life was broken like the surface of a pond

when the soft winds skip lightly over it.

The fields of the Wongsu and the fruit trees of the Makai produced nothing.

It was worse for the Wongsu.

Their field crops withered.

The wild game, thirsty and pained with hunger,

scampered higher into the mountains

in search of small pools or green bushes and berries.

The Wongsu hunters, on whom the village now depended,

did not pursue the game at first, fearful of encountering the dragons

or becoming lost in the deep ravines where the shadows

were as dark as the thoughts of jealous men.

But one day a Wongsu hunter, made bold by hunger

and pity for his starving wife and children,

tracked a small goat to the very crest of the mountains,

but he did not go near the dragon caves.

Now, and for the first time, a man of Wongsu looked down upon the village of the Makai.

Crawling closer so he could see but not be seen —

for this is the first rule of good hunters —

he watched the Makai tug their great nets from the sea, heavy with hundreds of silvery fish.

He watched them scale and clean them and leave some to dry, and he wondered.