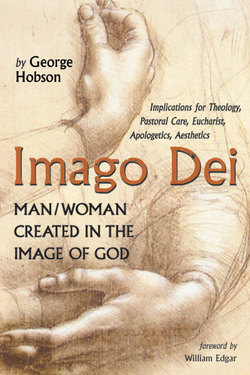

Читать книгу Imago Dei: Man/Woman Created in the Image of God - George Hobson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеThe texts in this book, with one exception, were written over the last fifteen years and vary widely in style and subject matter. I have updated them where this seemed necessary. Apart from the three long essays, they were given as talks in parish churches. All of them are rooted in one way or another in the seminal biblical text in Genesis 1:26–28. Verse 26 reads:“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; man and woman he created them.” This foundational Judeo-Christian anthropological principle is a revelation. It is not an inference from nature. One cannot read it off from the world around us. I believe it to be a fundamental God-given truth that Jews and Christians, in different ways, can use to bring theoretical coherence and practical responses to many of the challenges and baffling questions facing mankind in our day. How is it that lawful order and structure in the universe are, by a variety of means, apprehensible by human beings? Or how is it that what we call beauty is a reality eluding exact definition yet one that men and women perceive and cherish and seek tirelessly, in all cultures, to express in one form or another? What is this “beauty?” What does it signify? Or further: Is there a common human nature, an anthropological unity underlying the various ethnic and tribal expressions to be found on our planet, or is any such notion, or imagined commonality, necessarily a social construct, be it religious, philosophical, or juridical? (The relevance of this issue to current discussions about human dignity and rights cannot be exaggerated.) Or again: Whence comes the essentially religious nature of human beings, in the sense that we all experience a hunger for a transcendent reality, an inner longing for justice, peace, love, joy, freedom, and immortality, even within the existential reality of violence, cruelty, oppression, suffering, and death that characterizes human history? Whence comes this yearning for plenitude—for the absolute, for dynamic perfection—when the daily reality of human life falls far short of any such ideal or hope? How are we to understand the relation of this longing for a supranatural truth and love uniting human beings and indeed all creatures, with the intuition we also have of being ontologically integrated in an infinitely complex earthly and cosmic natural environment to which and, in a mysterious sense, for which we feel ourselves to be responsible?

The first two papers in this collection that make up Part One broach the question of our knowledge of God through natural theology on the one hand and—with specific reference to the resurrection—through divine action/revelation on the other. Emphasis is put in the first paper on a kind of natural theology based not on philosophical argument of the Thomistic sort, but rather on the explanatory power of theologically based insight into the natural world, even if such insight cannot actually give us personal knowledge of the Creator. By virtue of our being made in God’s image, we have the capacity to intuit, discover, and explore the phenomenal order in every aspect of the universe. All of these aspects are integrated in a coherent unity which, upon reflection, makes nonsense of the notion that sheer chance has produced the cosmos and everything in it, including human life. It is not that chance is absent, but rather that it is to be discerned within an overall context of law, in a relationship that allows a creative balance of freedom and order in the deployment of energy and matter. I devote a number of pages to reflections on mathematics, cosmology, and evolution, and conclude with a few thoughts on beauty and mystery.

In the second paper what is underlined is the impossibility, in our finite and fallen state, of our knowing the true God without his self-revelation. The supreme moment of this divine self-revelation is the resurrection of Jesus Christ. But it must also be evident that if mankind were not made in God’s image, we could not possibly either desire or receive this divine self-revelation. At the heart of Christ’s resurrection is the revelation of the God who is life and love. This corresponds perfectly to the deepest desire in the heart of all of us, even in our alienated state. I consider at some length the theme of Christ’s second coming as the necessary conclusion to his redemptive action on behalf of mankind, and I go on to reflect briefly on the nature of life after death and on the final judgment.

My underlying point in both essays in Part One is that we would not be able to know God in any way whatsoever—neither by reflection nor by intuition nor by revelation—if he had not created us in his image.

The lengthy essay on the imago Dei that follows in Part Two is an intensive discussion of this seminal anthropological revelation in Genesis 1 and serves as the centerpiece of the book and the thematic reference for all the other texts. It starts off with a discussion of genocide that leads into a sustained critique of the nihilistic side of modernity and postmodernity, of which, I suggest, the underlying cause is our progressive rejection of the Judeo-Christian God since the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and hence, logically, of man/woman as made in God’s image. In no way do I presume to cover all aspects of what we may take the imago Dei to signify, but I do wish to underline the great importance, in our age of genocidal violence, technological revolution, genetic and genome manipulation, moral anarchy, and anthropological confusion, of recovering the basic truth about mankind provided by this biblical vision. Western society’s retreat from God and from the imago Dei has opened up a black hole in our culture, sucking us into successive forms of ideological totalitarianism made possible by technological power and seeking, at bottom, to transform the ontological truth of man-made-in-God’s image into its inversion, God-made-in-man’s image.

My analysis of the imago Dei is to be seen against this dark historical backdrop. I argue that the core meaning of the imago Dei is relational, and that qualitative factors, such as our rationality and moral freedom, are to be understood within this relational context. We are ontologically bound to our Creator. Our rebellion against him entails an inversion of the imago but not an effacement of it, and we are seeing the ultimate outworking of this inversion in our day. We are alienated from our Creator but not essentially separated from him because our very nature is to be made in his image. Herein lies the explanation of all our idolatries but also of the possibility of our being redeemed by our merciful Creator. Jesus Christ, the Son of God, our Redeemer, is the very image of God (Col 1:15; Heb 1:3), who can identify with us and become man and save us precisely because we are made in his image, that is, in God’s image.

I go on to discuss at length the nature of this Creator and Redeemer God in whose image we are made, as he has revealed himself in the Old and New Testaments. This leads on to cosmological and teleological issues, remarks about homosexuality, and finally to a concluding exploration of the imago Dei in relational terms, as noted above, showing how human dignity and unity, freedom, reason, and our human capacity to love, are all rooted in our nature as creatures made in God’s image. It is, indeed, the ontological truth of this revelation, restored to the positive relational mode through the incarnation, passion, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ, followed by the sending of the Holy Spirit, that accounts for the gradual emergence, in cultures shaped by the church, of concepts such as the unity of mankind, the essential value and dignity of all human beings (regardless of qualitative inequalities of whatever kind), the worth of the individual person and his/her vocation to be free and not enslaved, and the consequent belief in human rights.

I close with a few remarks recalling the earlier analysis of human rebellion as it moves in our day to eliminate God and replace him with man. By means of a technology-based ideology of individual autonomy and a false idea of freedom, we are trying to appropriate and exploit for our selfish purposes all the variety of gifts that God has given us in his creation and through his redemption in Jesus Christ. Blindly, violently, foolishly, we are pulling up the roots of the tree in which we have life. Having excluded, in the name of human freedom, all reference to a transcendent source of being, we have imprisoned ourselves. On the basis of an evolutionist understanding of human nature, we have confirmed a body/mind dualism that has us now presuming to dictate to material reality, including to biological structures and our own human bodies, whatever our subjective feelings and desires want it to be. Our minds rule, our bodies are mere matter. This is sheer illusion, a hubristic power-grab. Only sexual and social anarchy can result. Rebellion and self-hatred masquerading as a noble quest for freedom from constraints and limits for our “authentic self, ” is leading to widespread despair and the loss of the very sense of identity we are straining to establish. The “man” I referred to above, whom we are intent on putting in God’s place, is inhuman. Having cast the Creator aside, we are de-naturing his creature, man/woman, and damaging all the other creatures of the world it is our calling to care for. We are enslaving ourselves, while thinking we are doing just the opposite. It is tragic.

Part Three, which includes a short essay on the Holy Spirit, baptism, the new birth, and the charismatic gifts, is hands-on, practical material, and includes notes from parish seminars given by my wife Victoria and me on the subject of Christian identity, pastoral care and counselling, and inner healing through prayer. I have retained the repetitions in the material because they may be pedagogically useful by impressing on readers the principles and procedures under discussion. My aim is to provide basic scriptural and practical guidelines to equip Christians in local parishes, house churches, prayer groups, and other communal structures, with down-to-earth principles for living the Christian life and creating strong communities. I am convinced that these principles and procedures are essential for the building up of the body of Christ and are not adequately taught and deployed in the church today, either in theological colleges or in parishes—this is my reason for wanting to include these talks in this volume of essays. If we are to carry out our mission of evangelism in the revolutionary environment of today’s world, we must be very clear as to who we are in Christ: sons and daughters of God the Father. We are new creations (Gal 6:5). It is our certainty about this identity that will enable us to be healed, trained, and anointed by the Holy Spirit in ways that go beyond what most Christians experienced in earlier generations.

This work of healing and training is not just the task of priests and pastors, though these ordained leaders should certainly have received the formation enabling them to train lay people in their communities to assist them in their pastoral care. The Christian believer, as a new creation in Christ through the work of the Holy Spirit, is called to be conformed to Jesus, who is himself the very image of God (Col 1:15; 2 Cor 4:4). The possibility of conformity to Jesus presupposes the essential nature of human beings as created in God’s image. The doctrine of the imago Dei is therefore basic to all pastoral work in the church—hence, as I said above, the inclusion of these hands-on notes in this collection of theological essays. The seminar talks, which, deliberately, I have hardly altered, attempt to show from a variety of angles how this plays out—or can play out—in the practical daily life of a Christian believer as he or she enters more and more deeply into his/her new spiritual identity as a son or daughter of God that is God’s gift through faith.

The essay in the next section, Part Four, is an in-depth study of the central sacrament of the church: the Eucharist. From a number of perspectives, including unity in the body of Christ, the Holy Spirit’s action in the Eucharist, and the issue of sacrifice, I explore the meaning and efficacy of the Passover and the Eucharistic celebrations. How is Christ’s body—crucified, sacramental, and ecclesial/mystical—present to us when we receive the bread and wine? While I do not explicitly develop the doctrine of the imago Dei in this piece, it must surely be evident that the spiritual efficacy of this central sacrament of the church, in which believers participate in the body and blood of Jesus, presupposes and depends on the prior ontological reality that the believers are created in God’s image, that is, in the image of Jesus.

Part Five consists of four talks on apologetics given in a church in Paris, which, once again, are underpinned by the biblical revelation of the imago Dei. The aim is to provide a few basic apologetical tools for Christians as they share their faith with unbelievers or inquirers. The church is under attack today on all sides, and Christians must be better equipped conceptually than we have been in earlier centuries to carry out our mission of spreading the gospel. Our love for our neighbor and our social action must be complemented by a stronger grasp of the intellectual challenges we face. I touch on matters such as cosmology, Darwinism, secularism, Christ/truth/Scripture, and Islam, showing in outline how the truth about human nature revealed in Genesis 1:26–28 illuminates, challenges, or brings correctives to each of these subjects. Other subjects could be added, of course, but I chose to focus on these.

Part Six shifts the perspective to the subject of aesthetics. In the lengthy opening essay, beauty is understood to be the radiance of divine truth. Herein lies the mystery of its glory. Man/Woman made in God’s image is called and gifted to apprehend this glory. Again, as in the essay on the imago Dei, I explore this biblical revelation and mount an in-depth critique of the reigning ideological “isms” of our day—materialism, productivism and the instrumentalization of nature it entails, consumerism, relativism, individualism (as distinct from individuality)—in an attempt to highlight our current alienation from nature and the impoverished sensitivity to beauty and truth that results from this. I cover some of the same ground as in the Imago Dei text in Part Two, and in talks three and four of Part Five, but from different angles. My hope is that what repetition there is will clarify further and reinforce the critique of late modernity that I am making.

Going on to consider certain aspects of Greek philosophical thought, I discuss the issue of form and contrast the Platonic intuition with the Hebraic and Christian vision. For the Greeks, the awareness of beauty arose from the contemplation of form, which was understood as the translation of being itself, and the rational order of the cosmos, into concrete manifestations; for the Hebrew and Christian mind, a beautiful form is an expression of God’s creative word. In both cases, form reflects metaphysical reality and manifests rationality. Herein lies its beauty, in which we are called to participate. Such a vision is utterly remote from modernity’s and postmodernity’s positivistic perception of the physical world, which sees concrete things, including the human body, as mere disposable matter that human reason and will are called upon to control and manipulate for utilitarian purposes. Any notion of participation in metaphysical reality is totally absent; reverence before form, wonder before beauty, have disappeared.

Next, I underline strongly the relational dimension of our connection with other objects/creatures in the world, as over against the functionalist attitude of our productivist societies. This involves a discussion of naming—the task given by God to Adam in the garden of Eden (Gen 2:19–20)—as it may be applied to science and art. It is the relational dimension between us and the world, rooted in the imago Dei and in the stewardship of God’s creatures that the imago Dei entails, that enables us to name creatures, to observe and know them, and that opens human beings to the perception and experience of the mystery of beauty. We are equipped by nature to investigate the world, scientifically and artistically. Our relation with creatures is the counterpart of our imago Dei relation with God. This means, of course, that our inversion of the imago through our rejection of the true God (original sin) has brought about a progressive alienation from nature and a ruinous exploitation of its bounty, culminating in the catastrophic ecological/environmental predicament mankind is facing today.

My concluding remarks in this paper speak again of beauty as the radiance of truth, a radiance that glorifies forms but also points beyond them to their Source, the Creator God who is love. A short disquisition on art and light closes the essay.

The autobiographical talk that follows examines the subject of poetry and art from the perspective of my own experience as a poet who, as a Christian, is faced with the challenge of communicating with a largely secular audience that is increasingly ignorant of and often hostile toward the Christian gospel. Moreover, regardless of the audience that he/she is addressing, writers who are new creations in Christ cannot write as they did before they were born again. My reflections on what I call true art are an effort to respond to these challenges.

Finally, a concluding short talk gathers together in summary form many of the points made earlier about the imago Dei and aesthetics in a final effort to show how, at a practical level, it is the truth of the imago Dei that inspires and makes possible the human quest, in particular through the arts, to express and give form to what is experienced—by all peoples everywhere—as beauty.

My hope is that the range and variety of the texts in this book will incite renewed reflection on the anthropological revelation in Genesis of the imago Dei, man/woman as created in the image of God. In our age of transhumanist ambition, which is rooted in the hubristic denial of a Creator God and in a corresponding refusal of the notion of a created and good God-given human nature—twisted because of the Fall, yes, but good in its created essence—it is of the greatest importance for the future of the church and for the well-being of our society to develop and defend this biblical revelation. The core of the modern project, as it takes ultimate shape in our technological age, is auto-salvation. For the transhumanist, though he/she wouldn’t use salvation language, this objective is explicit and deliberate. The aim is not so much to augment the human being as to replace him/her with a technologically engineered, new and better model. This delusory enterprise—the definitive tower of Babel—is clearly a counterfeit of God’s redemptive action through Christ to set right his sin-marred creation by opening for us the possibility of becoming new creations. There is no fixed, divinely created human nature, we are told. Man is a faulty organism and must be reconceived and reconstituted by himself. Such an objective is perceived to be the fulfillment of the process of evolutionary/historical progress, culminating in the kingdom of man, a simulacrum of the kingdom of God.

In the face of gnostic ambitions of this kind that both mock and mimic the creation and redemption of mankind through the Word of God, Jesus Christ, the truth of the imago Dei, in all its dimensions, is a tremendously powerful weapon in the hands of the church. As an anthropological principle, it is pertinent at every level of human reflection and action, in response to the moral and spiritual cacophony of modern life. My wish is that these texts, bouncing off each other in multiple directions, may illuminate for readers the truth and vital significance of this biblical revelation, by which is established ontologically and forever the true relation of human beings both to God their Creator and to the world—God’s good creation—that they inhabit.