Читать книгу Wings for the Fleet - George Van Deurs - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO: THE NAVY INVESTIGATES AVIATION

Washington Irving Chambers, Captain, United States Navy, was of medium height with brown hair that was beginning to grow thin and a half-moon mustache above his soft mouth. He had stood twenty-seventh in his 1876 class of forty-one graduates from the Naval Academy. In those days, promotion was slow. Two decades after graduation, during the war with Spain, he was a lieutenant commander at the Naval Torpedo Station in Newport, Rhode Island. Then followed successive tours of duty at sea. His first command was the schooner Frolic. Next came the gunboat Nashville, followed by the monitor Florida.

During the following years, Chambers had finally achieved the line officer’s goal—a battleship command—and wore his captain’s stripes with self-confidence and pride. Chambers worked for Admiral Dewey in 1904, but he did not accompany him to St. Louis when the Admiral watched Santos-Dumont fly his dirigible. When the Wrights flew from Fort Myer in 1908 and 1909, he was Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance, but there is no evidence that he took a professional interest in them. When the Wright brothers flew up the Hudson River to Grant’s Tomb, he witnessed the event from his command, the battleship Louisiana, but he was unimpressed.

Less than three months later, because of his familiarity with ordnance material, the Navy Department cut short his captain’s cruise before it had well begun and ordered him back to Washington for duty. He asked to stay at sea, but was told his “special abilities” were needed in Washington, and in December 1909 he became assistant to Captain Frank Friday Fletcher, who was Aide for Materiel to Secretary of the Navy Meyer.

Nine months later Chambers was handed the aviation mail as an additional duty. There was nothing in his past experience to qualify him in the new field of aeronautics, so he proceeded to read everything he, or the naval librarian, could find on the subject. The mechanical details of the flying machines, both proposed and in use, fascinated him. But he had never been in the air, or closely observed any aircraft, and could only assess what he read against his own seagoing background. Thus he began his new career with some of Langley’s fallacious reasoning and with no conception of a plane’s weight-power-wing relationship. He pictured a naval plane as an unusually handy ship’s boat. It cost about the same. The steering of it, up and down, or right and left, appeared to him as similar to the work of a boat’s coxswain.

In October, his old boss, Admiral Dewey, nudged the Navy closer to aviation. He recommended that in the future the Bureau of Steam Engineering and the Bureau of Construction and Repair design scouting vessels with space for aeroplanes.

In those days Navy bureau chiefs had no military superior. Congress gave each bureau an appropriation and held its chief personally responsible for the way the money was spent. By law each bureau head was the adviser on his specialty to the Secretary of the Navy, who alone could coordinate their activities. The chiefs were jealous of Dewey’s General Board, and they frequently stood together to oppose its advice to the Secretary. At other times they were rivals. Always there was a scramble for control of any proposed new Navy equipment. Thus Rear Admiral Hutch I. Cone, the engineer in chief, used Dewey’s recommendation to open a new round in this continuing competition. Within a week he was asking the Secretary to let him buy an aeroplane for the USS Chester, and hire an instructor to show an officer how to fly it. But the aides recommended waiting until planes were better developed. Chief Constructor R. M. Watt tried to belittle the General Board by proposing that an officer from his bureau and another from the Bureau of Engineering study aviation and advise the Department on its naval applications.

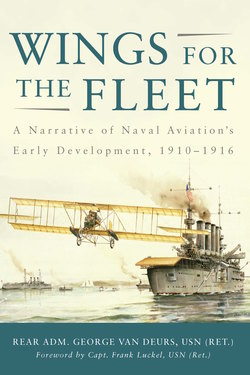

2. Captain Washington Irving Chambers, U.S. Navy.

Secretary Meyer was busy inspecting Navy yards on the West Coast when these papers were put on his desk. Assistant Secretary Beekman Winthrop, who was “acting,” pigeonholed the aides’ recommendations and sent Cone’s request to Dewey for comment. Then he told Watt and Cone that Chambers had already been detailed to advise the Department about aviation. He suggested they each appoint an officer to work with Chambers. The Bureau of Engineering appointed Lieutenant H. N. Wright, and the Bureau of Construction and Repair named Naval Constructor William McEntee, who had accompanied Sweet to see the 1908 flights at Fort Myer. Thus Chambers’ letter-answering job expanded into one of liaison before it was a month old.

The next few years, Dewey and Winthrop were naval aviation’s best friends. Their direct help, however, was limited. The General Board could only give advice, which the Secretary was not bound to accept. The Assistant Secretary dealt only with Navy yards, except when, in Mr. Meyer’s absence, he was “acting” secretary. Chambers took full advantage of this exception. Most of the pioneering moves which required the Secretary’s approval were signed, “Winthrop, acting.”

Chambers sent a summary of his first studies to the General Board. He believed that the performance and reliability of aeroplanes would improve rapidly. They would soon be able to land on, or take off from, a ship. Someday, they might even fight, but for the immediate future he recommended they be developed for scouting only. This last opinion did not suit one new Board member, Captain Bradley A. Fiske.

Fiske was a veteran of the battle of Manila Bay. He had arrived in the Navy Department from command of the Tennessee, had been told to study war plans, and had quickly concluded that the plans to defend the Philippines were inadequate. Two years senior to Chambers, he was an inventor who experimented with radio before Marconi and had developed a telescopic gun sight and an optical range finder.

3. Chief Constructor Richard M. Watt. (National Archives)

Bradley Fiske had never seen a flying machine in the air. No aeroplane had yet flown either from a ship or from the water. The Navy had neither a plane nor a pilot. Despite all this, at a meeting of the General Board, this little man, who ignored bothersome details to tackle big problems, proposed to defend the Philippines with four naval air stations. Each was to be equipped with one hundred planes to sink transports and boats if the Japanese tried to land in the islands. If they made the planes big enough, Fiske said, they could launch torpedoes against the transports.

Rear Admiral Richard Wainwright protested, “Why waste the time of the General Board with wildcat schemes?” The proposal was dropped and everyone forgot about it, except, of course, Fiske. His idea was an arrow, shot into the future. Two years later he was granted a patent on a torpedo plane.

A few days after this General Board meeting, Winthrop, “acting,” signed orders for Chambers and the two liaison officers to be present as official observers at the International Air Meet opening at Belmont Park on 22 October 1910. There, for the first time, Chambers closely inspected flying machines, met the men who had invented and were building them, and talked with the sportsmen fliers and professional pilots.

Most of the professional pilots knew little about the “why” of their machines. They had been parachute jumpers, balloonists, racing drivers, or circus stunt men. Few of them ever formally learned how to fly. They took off by luck, superstition, and rule of thumb, and then landed by sheer audacity and agility. They would try anything for publicity and big money. These men were the mainstays of the exhibition teams, but they bored thoughtful men like the Wrights and Curtiss. Chambers found them uninteresting because they could only discuss flying in terms of muscular exercises and sensations.

Eugene Ely, the self-taught flier from the West Coast, was an exception. Chambers found him an amiable young man. Curtiss liked and trusted him more than his other pilots. Unlike the daredevils, Ely had a logical theory of flight and a keen interest in the machines. He spent a lot of his time on the ground working with Glenn Curtiss. Both men were interested in producing aeroplanes that would be more useful than merely providing sport.

When he first met Glenn Curtiss, Chambers was surprised to find that this 32-year-old inventor looked more like a quiet, shy farmer in an oversized coat than a spectacular speed king. At first Curtiss could only find disconnected monosyllables to explain his machines. He would lay hold of an elevator and say, “down,” move it, and say “up.” Chambers mentioned an intelligence report on the Frenchman, Henri Fabre, and his takeoff from the water at Rheims. Could Curtiss build a machine that would fly from the water? This question seemed to spark Curtiss’ own enthusiasm and dispelled his self-consciousness. He talked more easily of his past failures and his present hopes. He and Chambers discussed hydroaeroplanes at some length. When the meet was over, Chambers was convinced that Curtiss’ hydro would soon succeed, and Curtiss believed that, when it did, the Navy would be his customer.

Among the aeroplane builders, Chambers thought the Wrights were using the best approximation of scientific methods. At the same time, he was appalled at how much they all relied on “cut-and-try” procedures.

They had to, the Wrights pointed out. No adequate aeronautical engineering knowledge existed. There was no aeronautical mathematics. Would planes improve faster if some sort of national laboratory developed basic information for all designers? Could planes fly from a ship? Chambers put these questions to almost everyone at Belmont Park, and the answer they gave him was yes to both questions.

The Wrights were cordial and obviously eager to interest the Navy in their work. However, Chambers felt some intangible, persistent reserve. Possibly, since they knew he was also talking with Curtiss, it was a shadow of the hatred engendered by the patent suit. After the Belmont Air Meet, Chambers and Curtiss exchanged ideas and frank opinions in personal letters. Chambers did the same with Loening, the Wrights’ manager. But he had few such exchanges with the Wrights themselves. Whatever caused this personal stiffness in the Wrights, it never kept Chambers from doing business with them.

The mechanical details of the forty-odd machines at Belmont Park claimed most of Chambers’ interest. Beginning with Santos-Dumont’s tiny monoplanes, he studied them carefully. He admired the way French fliers pulled parts from crates, quickly assembled them, and then took off. They never wasted time with preflight adjustments or warm-ups, like other pilots. Could similar machines be built with parts small enough to go through a cruiser’s hatches? The obvious instability of all planes started the captain following Langley’s thinking. He convinced himself that ship-design methods and automatic-steering engines, like those of a torpedo, could make an aeroplane as stable as a skiff on a pond.

He watched aviators who, in order to win big cash prizes, flew in bad weather, but he did not give their piloting the attention he gave their machines. Maybe he thought flying easy because the boasting of the dare-devils sounded like old sailors’ yarns, or because they broke a few machines but no bones. Without much investigation he concluded that any seagoing officer could quickly master an aeroplane. Once learned, he assumed, flying would be like riding a bicycle; the trick would never be lost.

Chambers left the eight-day Belmont Park meet convinced that the Navy could and should develop naval aircraft. He thought a naval aeronautical organization and a national aeronautical laboratory desirable to speed the project. Thereafter he became a missionary with a cause. Opponents’ arguments always made him more certain that he alone saw the light. No matter how many details of his conclusions would prove erroneous, he would remain dedicated to the improvement of naval aviation.

4. Eugene Ely and J. A. D. McCurdy—both members of the Curtiss Exhibition Team. They and eleven other members of the team thrilled the countryside with their spectacular flying in 1910 and 1911.

As naval aviation grew and spread into the Fleet, some unknown individual coined two terms which distinguished enthusiasts for naval aviation from their more conservative and skeptical brother officers. It derived quite naturally from an aspect of their dress. All naval officers wore black shoes; the aviators, brown shoes. Thus, flying officers were “brown shoes,” while shipboard officers became the “black shoes.” For some years before World War II, it was the “brown shoes” versus the “black shoes.”

After the meet at Belmont Park, Chambers figuratively put on brown shoes for the rest of his life.

On 3 November 1910, another air show opened at Halethorpe Field near Baltimore. Again, Chambers left his desk in Washington to attend. Many of the Belmont pilots sent their planes to the Baltimore show, but an expressmen’s strike held up delivery of most of the planes and, on opening afternoon, only two Curtiss planes flew. One of these was flown by Eugene Ely. Ely was feeling pretty confident. He liked to fly. He was making big money and a good name in an exciting business, which promised an unlimited future. His wife, Mabel, was also an aviation fan.

A rain storm stopped the show; by evening tent hangars were blown down and Ely’s planes were smashed. Since nothing could be done at the field in such weather, Gene and Mabel went shopping in Baltimore. When they returned to the hotel at the end of the wet afternoon, they met Captain Chambers.

During their conversation, Chambers mentioned he had just asked Wilbur Wright for a pilot and a plane to fly from a ship. Wright had flatly refused all help, saying it was too dangerous. He would not even meet Chambers to talk it over. Chambers was taken aback because it was Orville’s suggestion in 1908 that had given him the idea. “I had hoped it would get the Navy interested in planes,” he said.

Gene Ely quickly asked for the job. “I’ve wanted to do that for some time,” he told the surprised captain. Ely would furnish his own plane and he asked for no fee. He had three reasons for his eagerness. He had argued shipboard takeoffs with other fliers and he wanted to show them it could be done, he wanted the publicity, and he wanted to do a patriotic service.

Chambers wanted to get Curtiss’ consent. “Not necessary,” Ely assured him. “I make my own dates under our contract.” That was a happy chance. As a matter of fact, Curtiss did his best to talk Ely out of it. Maybe he agreed with Wilbur Wright and thought it too dangerous. He argued that a failure would hurt plane sales. Mabel Ely believed he feared success even more. It might detract from the naval value of his hydroaeroplane.

Back in Washington, Wainwright turned down Chambers’ proposal to let Ely fly from a cruiser. Chambers’ boss, Captain Fletcher, told reporters the Navy had no money for such things. Meyer returned to Washington; in Baltimore that same day, Chambers asked Curtiss and Ely to back his appeal with technical arguments. Only Ely went to Washington with him to confer with Meyer.

Secretary Meyer was back at his desk after his long inspection trip. Undoubtedly Wainwright had coached him before the conference. Ely never forgot how the Secretary covered his technical ignorance of aircraft and ships with an imperious coldness, and he never forgave him for calling Ely’s plane a mere carnival toy when he turned down the proposed shipboard takeoff.

Then John Barry Ryan, a millionaire publisher and politician, got into the act. Two months earlier he had organized financiers, investors, and scientists interested in aeronautics, with a few pilots, as the U. S. Aeronautical Reserve. He furnished this organization with a Fifth Avenue clubhouse, provided several cash prizes for aeronautical achievements by its members, and made himself commodore of the organization. One of these prizes was $1,000 for the first ship-to-shore flight of a mile or more. Ryan was in Washington to pledge the club’s pilots and their planes to the Army and Navy in case of war, when he heard of the Chambers-Ely plan and reopened the subject with Secretary Meyer.

When Ryan urged Chambers’ proposal, Secretary Meyer responded that the Navy had no funds for such experiments. Ryan then offered to withdraw the $1,000 prize, which the non-member Ely could not win anyway, and use it to pay the costs of the test. Meyer had little interest in planes, but he was an accomplished politician, and he knew Ryan could swing votes in both Baltimore and New York. After consulting the White House, he agreed that the Navy would furnish a ship, but no money. Thereupon he left town.

Winthrop, “acting,” acted in a hurry. He rushed the Birmingham, commanded by Captain W. B. Fletcher, to the Norfolk Navy Yard and told the yard commandant to help equip her with the ramp which Constructor McEntee had designed. The ship was a scout cruiser, with four tall stacks. Her open bridge was but one level above the flush main deck. On her forecastle, sailors sawed and nailed until they finished an 83-foot ramp, which sloped at five degrees from the bridge rail to the main deck at the bow. The forward edge was 37 feet above water.

Meanwhile, Henning and Callen, Ely’s mechanics, worked at Piny Beach, where later the Hampton Roads Naval Base would be built. Using bits shipped from Hammondsport and pieces salvaged in Baltimore, they built a plane. Ely got there on a Sunday in foul weather. He added cigar-shaped aluminum floats under the wings and a splash-board on the landing gear. Late in the day he saw the plane—without its engine—aboard the Navy tug Alice, headed for the Navy Yard. The engine had been shipped; no one know when it might arrive.

Gene Ely was not a worrying man. But the storm at Baltimore had cost him money. Shortly before Belmont, a speck of paint in a gas tank vent had robbed him of fame and a $50,000 prize. In previous months other crack-ups had bruised his body and damaged his pocketbook. These mishaps taught him how tiny, unexpected flaws could foul up a flight. Each time he charged it off to experience and tried again. Since his interview with Mr. Meyer, the cruiser flight had become a must. To his original motives, Ely had added an intense desire to show Secretary Meyer the error of his ways. At the same time he knew that, if he failed in his first try, Meyer would never give him another chance. And so Ely was worried when he joined his wife and Chambers.

5. Ely’s plane on the USS Birmingham, just prior to his flight.

At the old Monticello Hotel in Norfolk, Ely told reporters, “Everything is ready. If the weather is favorable, I expect to make the flight tomorrow without difficulty.” Mabel knew that her husband was whistling in the dark. He had not seen the platform. The plane was untested. He hoped his engine would come on the night boat. But she had complete confidence in Gene, so she enjoyed a seafood dinner and untroubled sleep. Ely ate little, turned in early, and slept poorly.

In the morning, as he worried into his clothes, the clouds looked level with the hotel roof. He skipped breakfast and took the Portsmouth ferry.

Callen and Henning had hoisted the plane aboard the Birmingham, pushed it to the after end of the platform, and secured it with its tail nearly over the ship’s wheel. Only 57 feet of ramp remained in front of the plane. Henning was worried. But Callen reassured him. “Old Gene can fly anywhere,” he said. Then Ely’s chief mechanic, Harrington, arrived with the engine. The three were getting it out of the crate when Ely and Chambers boarded the ship.

At 1130, sooty, black coal smoke rolled from the Birmingham’s stacks as she backed clear and headed down river. Two destroyers cleared the next dock. One followed the cruiser; the other headed for Norfolk to pick up Mabel Ely and the Norfolk reporters.

Going down river, Ely helped his men install the engine. He wanted to double check everything to avoid another failure; besides, the familiar work eased his tensions. He blew out the gas tank vent twice. In spite of squalls, they had the plane ready before the ship rounded the last buoy off Piny Beach. They had almost reached the destroyers Bailey and Stringham, waiting with Winthrop and other Washington officials, when another squall closed in. A quarter mile off Old Point Comfort, Captain Fletcher anchored the Birmingham. Hail blotted out the Chamberlain Hotel.

It was nearly two o’clock when that squall moved off to the north. Ely climbed to his plane’s seat. Henning spun the propeller. Under the bridge the wireless operator tapped out a play-by-play account of the engine testing. When the warm-up came to an end, nobody liked the looks of the weather. Black clouds scudded just above the topmast. The cruiser Washington radioed that it was thick up the bay, and the Weather Bureau reported it would be worse the next day. Chambers nodded toward the torpedo boats. “If this weather holds till dark,” he said, “a lot of those guys will go back to Washington shouting ‘I told you so.’”

By 1430 the sky looked lighter to the south. Captains Fletcher and Chambers decided to get under way. Iowa-born Ely could not swim, feared the water, got seasick on ferry-boats, and knew nothing about ships. He thought the cruiser would get under way as quickly as a San Francisco Bay ferry. He had no idea that the windlass he heard wheezing and clanking under the aeroplane platform might take half an hour to heave 90 fathoms of chain out of the mud. So he paced first the bridge, then the launching platform. Then he climbed into his seat and tried the controls. Sixty fathoms of chain were still out. Henning spun the propeller. Ely opened the throttle and listened approvingly to the steady beat. Under the plane’s tail, the helmsman at the wheel took the full force of the blast.

Ely was ready. He idled the engine and waited. Then he gunned the engine to clear it, twisted the wheel for the feel of the rudder, rechecked the setting of the elevator, and looked back at the captains on the bridge wing. They looked completely unhurried.

Then Ely noticed the horizon darkening with another squall and he began to wonder why the Birmingham did not start. He looked at Chambers, pointed at the approaching blackness. The captain nodded. He knew it would be close, but he could do nothing. Thirty fathoms of chain were still in the water.

Gene Ely checked everything again, and stared at the squall ahead. He seemed about to lose his chance because the Navy was too slow. At 1516 he decided he would wait no longer for the ship to start steaming into the wind. If ever he was going to fly off that ship, it had to be now. He gave the release signal.

Harrington, who knew the plan, hesitated. Ely emphatically repeated his signal. The mechanic yanked the toggle, watched the plane roll down the ramp and drop out of sight. Water splashed high in front of the ship. Then the plane came into sight, climbing slowly toward the dark clouds. Men on the platform and bridge let out the breath they had held. One of them spoke into a voice tube, and the wireless operator tapped out, “Ely just gone.”

In 1910, Curtiss pilots steered with their rudder, balanced with their ailerons and kept the elevator set, by marks on its bamboo pushrod, either at a climb, level, or a glide position. In order to dip and pick up a bit more speed, Ely took off with his elevator set for glide. Off the bow he waited the fraction of an instant too long to shift to climb. The machine pointed up, but squashed down through the air.

Gene felt a sudden drag. Salt water whipped his face. A rattle, like hail on a tin roof, was louder than his engine. He tried to wipe the spray from his goggles but his gloved hand only smeared them, so he was blinded. Then the splashboard pulled the wheels free of the water. The rattle stopped. He snatched off his goggles and saw dirty, brown water just beyond his shoes.

6. The wireless operator tapped out, “Ely just gone” as the frail little biplane left the deck of the Birmingham, 14 November 1910, and the first flight from a surface vessel became an accomplished fact. (National Archives)

The seat shook. The engine seemed to be trying to jump out of the plane. Ely’s sense of direction left him. There were no landmarks, only shadows in the mist, and that terrifying dirty water below. He swung left toward the darkest misty shadow. He had to land quickly. On the ground he might stop the vibration, take off again, and find the Navy Yard. He wondered if the bulky life jacket that fouled his arms would keep him afloat if the plane splashed.

A strip of land bordered by gray, weathered beach houses loomed ahead. Five minutes after the mechanic had pulled the toggle, Ely landed on the beach at Willoughby Spit. “Where am I?” he asked Julia Smith, who had dashed out of the nearest house.

“Right between my house and the yacht club,” she said.

It sounded funny but it wasn’t. He knew the splintered propeller would not take him to the Navy Yard. He had failed. He blamed himself bitterly for the split second delay in shifting the elevator. Now he knew how to do it without hitting the water, but would he ever get another chance?

Boats full of people converged on the yacht club dock. Their enthusiastic congratulations confused him. “I’m glad you did not head for the Navy Yard,” Chambers told him. “Nobody could find it in this weather.” Captain Fletcher agreed. John Barry Ryan offered him $500 for the broken propeller. “A souvenir of this historic flight,” he explained.

Ely figured that in not making the Navy Yard, he had failed, and Chambers and Ryan spent the evening trying to convince him that he had succeeded. His particular landing place was unimportant. It would soon be forgotten. The world would remember that he had shown that a plane could fly from a ship, and that navies could no longer ignore aeroplanes. Ely did not cheer up until Chambers promised to try to arrange a chance for him to do it again. “I could land aboard, too,” was Ely’s comment.

The next morning Ryan’s valet wrapped the splintered propeller in a bathrobe and carried it into his pullman drawing room. There Ryan gave a champagne party until train time, presented Ely with a check for the propeller, and made him a lieutenant in his U. S. Aeronautical Reserve. After the train pulled out, Gene spent the check on a diamond for Mabel.

The morning of 15 November 1910, the Birmingham flight filled front pages all over the United States and Europe. Foreign editors speculated that the United States would probably build special aviation ships immediately. American editors, more familiar with naval conservatism, said the flight should at least lead Secretary Meyer to ask for appropriations for aviation. But Wainwright’s friends belittled the performance. A ship could not fight with its guns boxed by a platform. A masthead lookout, they said, could see farther than Ely had flown.

And so it went and so it would go for a long time, this argument between the Navy’s black shoe conservatives and the brown shoe visionaries.