Читать книгу Know the Truth - George Carey - Страница 7

1 No Backing Out

Оглавление‘It is perhaps significant that though state education has existed in England since 1870, no Archbishop has so far passed through it. The first Prime Minister to do so was Lloyd George. Nor has anyone sat on St Augustine’s Chair, since the Reformation, who was not a student at Oxford or Cambridge. Understandably nominations to Lambeth have been conditioned by the contemporary social climate, but such a limitation of the field intake is doubtless on the way out. It is inconceivable that either talent or suitability can be so narrowly confined.’

Edward Carpenter, Cantuar: The Archbishops in Their Office (1988)

AS THE DOOR OF THE OLD PALACE BANGED behind Eileen and the family as they departed for the cathedral, I was left alone in the main lounge to await the summons that would most certainly change the direction of my life. At lunchtime with my family around the kitchen table there had been nervous laughter as Andrew, who had had his hair cut that morning, recounted hearing another customer talk about the ‘enthornment’ of the new Archbishop. We all agreed that that was a great description of it, although another of the family volunteered, ‘At least he didn’t say “entombment”.’

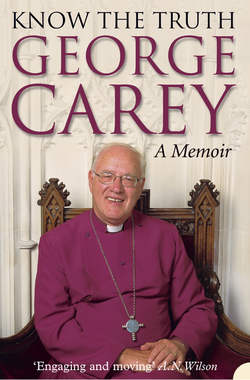

Somewhere in the building Graham James, my Chaplain, was sorting out the robes I would shortly wear. From the lounge window I could see and hear the crowds of people teeming around the west front of the cathedral. They were there to capture a glimpse of the Princess of Wales and other dignitaries including the Prime Minister, John Major. I could not help thinking wryly that within twenty yards of where I was standing another Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, had met his death in the same cathedral on 30 December 1170. My journey from this room was not going to lead me to his fate, but it was bound to bring me too in touch with opposition and conflict, as well as with much joy and fulfilment. The massive, enduring walls of the cathedral overshadowing the Old Palace however were a reassuring sign that the faith and folly, the strengths and weaknesses, the boldnesses and blunders of individual Archbishops are enveloped by the tender love of God and His infinite grace.

The television was on in the room, and I could hear Jonathan Dimbleby and Professor Owen Chadwick solemnly discussing the significance of the enthronement of the 103rd Archbishop of Canterbury. Professor Chadwick, a well-known Church historian, was reminding the viewers of the significance in affairs of state of the role of the Archbishop, an office older than the monarchy and integral with the identity of the nation.

Graham swept in with the first set of clothing I had to wear. ‘We’d better get you dressed, Archbishop,’ he said. ‘There’s no backing out now!’

I put on my cassock as I heard Owen Chadwick say that today, 19 April, was the Feast Day of St Alphege, a former Archbishop of Canterbury who, in 1012 ad in Greenwich, was battered to death by Vikings with ox bones because he refused to allow the Church to pay a ransom for his release. It seemed a hazardous mantle I was about to don.

Suddenly a great deal of noise erupted outside, and we walked over to the window to see the Prime Minister arrive with several other Ministers of State. He waved to the crowds and was ushered into the cathedral.

The whole world, it seemed, was present at the service in one way or another. Not only all the important religious leaders in the country – Cardinal Hume and Archbishop Gregorius, Moderators of the Church of Scotland, the Methodist Church and the Free Churches – but also the Patriarchs of the four ancient Sees of Constantinople, Alexandria, Jerusalem and Antioch. Billy Graham was present as my personal guest and as someone whose contribution to world Christianity was unique and outstanding. Cardinal Cassidy represented Pope John Paul II and the Pontifical Council for Christian Unity. Every Archbishop in the Anglican Communion was present, as was every Bishop in the Churches of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

Behind me Dimbleby and Chadwick were now speculating about the new Archbishop. I caught several of the comments: ‘A surprising appointment … he has only been a Bishop less than three years … Yes, an evangelical, but open to others … was born in the East End of London … working class … No, certainly not Oxbridge, but has taught in three theological colleges and Principal of another … comes with experience of parish life as well as being Chairman of the Faith and Order Advisory Group … I think he will be an unpompous Archbishop.’

Mention of my background brought home to me how much I owed to my godly and good parents, who sadly were not here to share in today’s momentous events. How proud, and yet how humble, they would have felt. I smiled to myself as I recalled my mother’s loud comment when in 1985 I was made Canon in Bristol Cathedral: ‘Now I know what the Virgin Mary must have felt like!’ Eileen, rather shocked, wheeled on her: ‘Mum, that’s blasphemy!’ Mother, unrepentant, just smiled.

Yes, how thrilled Mum and Dad would have been; but as realistic Christians they would not be glorying in the pomp and majesty of the day, so much as in the service it represented. They would also be sharing in the tumult of my feelings, and my apprehension as I faced a new future.

Actually, I was not the slightest bit ashamed of my working-class background, which I shared with at least 60 per cent of the population. The popular press had of course milked the story thoroughly, and it was the usual tale of ‘poor boy makes good’ by overcoming huge obstacles to ‘get to the top’. How I hated that kind of language of ‘top’ and ‘success’. It encouraged the stereotype that I was a ‘man of the people’, and therefore in tune with the vast majority of the populace. There was no logic in that, as a moment’s thought should have reminded such journalists that David Sheppard’s background – to take one example of many – did not prevent him from being closely in touch with the underprivileged. Nevertheless, I hoped with all my heart that it was true, and it was very much at the centre of my ministry to represent the cares and interests of ordinary people, with whom I could identify in terms of background.

Some writers, astonishingly, had drawn the conclusion that because I came from an evangelical background my politics were essentially conservative. That was clearly not the case, but neither did it mean that I automatically identified with any particular political party. I saw my role as Archbishop as a defender of the principles of parliamentary democracy. I wanted to support those called to exercise authority, and I would later remind Prime Ministers of both major parties that I saw it as my duty to confront them if they embarked upon policies which I felt undermined the nation in any way.

But what kind of Archbishop was I going to be? As the 103rd Archbishop I was spoiled for choice if modelling myself on any of my predecessors was the way to proceed. Becket feuded so regularly with his King that he spent most of his time in exile. No, that was not for me. The quiet, scholarly Cranmer, perhaps, with whose theology I could identify; but, then again, he was too vacillating and cautious. Nearer my time perhaps one of the greatest of them all, William Temple – scholar, activist, social reformer and inspirer. Yes, a giant among Archbishops, but he was Archbishop of Canterbury for a mere two years during wartime. As a model for this post there were many great men to consider. It struck me that whatever inspiration I received from my illustrious predecessors, I had to be my own man. One thing I could depend upon was that the same divine grace and strength that the previous Archbishops had received was available to me too.

‘It’s time to go, Archbishop,’ said a smiling Graham, handing me my mitre, and then with a prayer we walked towards the door, leaving the television commentary still describing the scene within the cathedral as we advanced to be part of it.