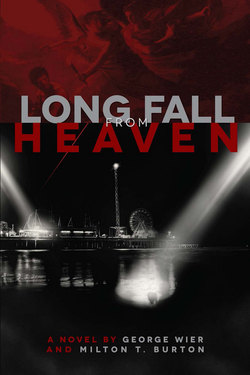

Читать книгу Long Fall from Heaven - George Wier - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление[ 3 ]

Micah Lanscomb and Cueball Boland had met five years earlier in a manner that in another time and in a more conventional place might have seemed strange. But Galveston is a port city, one with a threadbare allure many find irresistible. Its citizens are used to seeing the odd and the offbeat wash up on their shores.

Besides owning NiteWise Security, C.C. “Cueball” Boland was a pool hustler who operated his own billiards room a block off The Strand. Additionally, he was a retired Dallas cop who gambled moderately on poker, drank a fair amount of whiskey when the situation seemed to call for it (which it frequently did), and never failed to notice a pretty girl. Which is to say that he had all of the usual male vices and a couple he had cobbled together on his own. One vice he didn’t have was philandering because his wife, the former Myrna Hutchins, had been the center of his erotic universe since sixth grade. Nor could he ever be accused of disloyalty to friends. It was this last quality that had gotten him into trouble several times since his retirement eight years earlier. Or as Myrna often said, “C.C. is the only man whose learning curve is a straight line.”

Myrna said a lot of things like that, the kind of one-liners Groucho Marx would have appreciated. To his credit, Cueball listened to her. It was Myrna’s dry wit and uncanny sense of proportion that had attracted him to her long before the raging hormones of his early teens took charge of him, body and soul. Over the years it was his sense of loyalty that gathered to him a smattering handful of long-time friends, those few who had proven equal to the engulfing depths of his devotion. Much later in life, one of those friends was Micah Lanscomb.

Micah came into Cueball’s life from the rain, both literally and figuratively. Lanscomb was soaked, thin and weathered, and wore an impenetrable and taciturn demeanor. He was a head taller than his fellows and his shadow came before him, a palpable, inescapable thing that parted idle chatter like the wake of a great ship traversing middling waters. If the person meeting him were pressed on the matter, he would have said that the tall man was engaged in weighty matters, which, on the face of it, was the simple truth.

The pool hall was already quiet that fateful evening. The jukebox was being given its requisite thirty minutes to cool down, the plug disengaged and held against the wall by a racked billiard cue. The repairman who’d fixed the turntable motor and charged Cueball sixty bucks for the service call had advised a cooling down period each night—just one more thing Cueball could add to his religious regimen. It was either that or replace the damned thing, but Cueball had a soft place in his heart for old jukeboxes.

Outside the storm freshened, diminished, and came on once again with a howl. Then suddenly, like an apparition, a wet stranger appeared just inside the doorway, dripping on the bare wooden floors.

“Help you?” Cueball asked.

“I don’t have any money,” the stranger said, “but I’m hungry and I’ll wash dishes and clean the place up to cover it.”

Cueball closed his eyes and took a deep breath. When he turned and opened them again he saw his own reflection in the long mirror behind the bar—a nondescript gray man of sixty-two years with graying hair and a face that people found difficult to remember even when they were looking right at it. He was five ten and weighed a hundred and sixty-five pounds—neither tall nor short, neither stocky nor skinny. The clothes he wore were usually as unmemorable as the body they covered. A writer friend had once told him that there was something about him reminiscent of the flicker of old black-and-white film—quick celluloid images at the corner of an unfocused eye like those long-ago RKO newsreels from childhood afternoons spent at the quarter matinee.

He turned back to the man and stared at him. This was, beyond doubt, the kind of person he’d always resolutely, and with little success, sought to avoid—gaunt, hollow, needy, empty. A man like the thousands of others who wander this great and turbulent land looking for the one unnamable thing that might fill them, the undefined Holy Grail of their rootless existence. Yet there was a tiny something besides emptiness in the man’s eyes—something that said there was a story there worth hearing. And Cueball Boland was a man who listened to stories.

Cueball shrugged. “Pete,” he said quietly to the huge black man behind the bar. “Put a rib-eye on the grill and turn on the fryer. I do believe this poor guy could stand a square meal.”

“Much obliged,” the man said.

“Want a beer?” Cueball asked.

“Naw. A coke, maybe.”

Cueball’s hand had been resting on the cooler. He slid back the door, reached down and pulled up a bottle, maneuvered it under the church-key out of habit, his pale gray eyes locked with the stranger’s. Cueball didn’t bother to give the man a smile. The fellow was beyond caring about petty things.

The stranger took the coke and wandered over to a table, sat down and stared into the darkest corner of the room, oblivious. And so Cueball Boland went and joined him.

• • •

Micah Lanscomb’s story would come out, fully told, over a five-year period. Over those years, it would take the better part of a full case of Johnnie Walker Black Label whiskey to coax it forth.

As Lanscomb’s tale had it, in 1968 he’d left his family home in a dead end East Texas small town and made his way westward to San Francisco and the mecca of the children of Aquarius, the intersection of Haight Street with Ashbury. After weeks of hanging out with flower children, smoking dope from tall bongs between intermittent readings from Frodo’s passage of Moria and Gandalf’s consequent fall, he awoke one morning with the sure knowledge that his new hippie friends were full of shit to the precise degree they loudly clamored to be heard and understood. Which was not surprising given the fact they were, by-and-large, overgrown children, many of whom had been kicked from conservative nests as awkward and unfit offspring. It was, after all, a time of little understanding.

Experience was what Micah was looking for, experience with life and living. But in the cool California atmosphere of rebellion and irresponsibility there seemed little evidence that anyone else was on the same quest.

And so his quest turned inward. The drugs became harder drugs.

His first disaster came during a group campout on the beach at Malibu. He’d taken the ride down the Coast Highway with a busload of flower children in search of a score. During a particularly disturbing acid trip on the beach, one of the girls who had been traded around was murdered. Micah heard the screams in a starlit, acid-fueled darkness while wrestling with an eerie and ever-shifting reality. The stars overhead had become streaky, violent arcs. The sand beneath his bare feet sucked away at him as if drawing his life force downward from his heart. At first he thought the screeches were that of a peacock from the neighbor’s yard back home and in his distant childhood, but soon they became something else entirely. By the time he gathered himself enough to launch forward to investigate, there was only the still and lifeless body, savaged and torn beneath the cold glare of a cheap flashlight. He hadn’t loved her. No one had loved her, to his knowledge. And Micah Lanscomb hadn’t saved her. She was as much Kitty Genovese as she had been Susan “Sun-energy” Glover of the long, willowy legs and blond, Galadriel tresses. And she was dead.

He walked away that night. Walked away from California.

Death very nearly found him in a jailhouse in a small Nevada desert town at the hands of a sheriff’s deputy who didn’t care to stomach his smell. The deputy had tried to use him for a punching bag. Micah took the blows one by one up to the moment he realized the man wasn’t going to stop until his target ceased breathing. He then reached out two wiry arms past the deputy’s flailing limbs, applied an exact amount of pressure to his carotid artery, and relieved the deputy of consciousness long enough to liberate himself from jail, town, and the sovereign State of Nevada.

Eastward he walked, over mountains and across plains. He swam rivers, camped out with the ragged flotsam of humanity, and stopped when the Atlantic lapped at his ankles. There being no place further to go, he came home to Texas.

Four years had passed in a twinkling. His father was dead and his mother had remarried and moved off to Ohio. The town of Wilford was a husk of its former self. The home place, a two-bedroom shotgun house, was still standing empty. He took up residence. Two weeks after he hit town, he got a job at the local jail. Within five years he was the county sheriff. The locals, insular and suspicious of what they, in this late day, still called “the laws,” liked his diplomatic approach to law enforcement.

In 1979 he attended a symphony concert at Sam Houston State University, fifty miles away. The highlight was a Juilliard harpist named Diana Sulbee. He watched her from the first row, enchanted with her beauty and with the way she merged herself, body and soul, with the music that flowed as clear and crystalline as a cold mountain stream from her precious, slender fingers.

After the concert he went backstage, spoke to her briefly, and then surprised himself by asking her to dinner. Inexplicably, she accepted. They were married five days later before the Justice of the Peace in Wilford.

For two of the briefest and most beautiful years of his life, Micah Lanscomb was happy. That happiness was shattered when Diana was killed by an eighteen-wheel tractor-trailer rig whose driver failed to yield the right of way on an Interstate 45 feeder ramp and plowed over her sports car.

His wife’s death was his penance, Micah felt, for having let Susan Glover die that dark California night all those years before.

After the funeral—which was the largest gathering ever seen in the isolated and insular little town—Micah handed his badge and his gun to his senior deputy and pressed the keys to his truck into the bronzed hands of the Mexican grave digger. Then he began walking, yet again. This time south.

Micah walked until he met ocean once more.

Below the Galveston seawall in the turbulent waters of the Gulf, he purged himself of everything, both ugly and beautiful, and very nearly drowned in the bargain when a rip-current pulled him further out to sea. But he knew, instinctively, anything good that comes must be paid for, and sometimes the price is dear.

The man who emerged from the waves and the rocks was a different man. A man finally at peace with himself. And it was that man upon whom Cueball Boland would, in carefully measured doses over the course of time, ladle out his trust and his devotion.