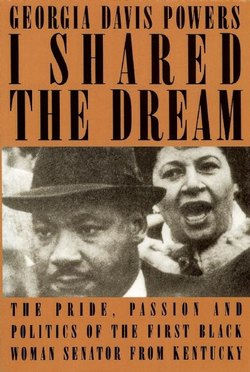

Читать книгу I Shared the Dream - Georgia Davis Powers - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

I was standing in front of the dresser mirror patting my hair when I heard the shot. A woman screamed, “Oh my God! They’ve shot Dr. King!” I rushed to the door of my motel room and flung it open. Uniformed policemen were entering the courtyard. Where had they come from so fast, I wondered? Later I learned that the police station was just seconds away on the corner.

Someone was pointing to the second floor. I looked up to my left and gasped. One of Dr. King’s knees stuck straight up in the air and I could make out the bottom of one foot. People in the courtyard had scattered to take cover. Without pausing, I hurried up the stairs closest to my room. Reaching King’s room, I stepped inside and saw Andy Young and Ralph Abernathy, their faces grim, feverishly telephoning for an ambulance. They hardly noticed me, and I went out on the balcony.

Alone, I walked over and looked at Dr. King. He was lying in a pool of blood that was widening as I stood there staring. The bullet had pierced the right side of his neck. His tie had been severed from the knot. Both the knot and an inch of tie were sticking up. It is a picture permanently imprinted in my mind.

A siren wailed. I went over to the iron railing and looked down. A black ambulance, looking more like a patrol car, was making its way in. By this time the courtyard was crowded with people, many crying or praying.

Two medics from the ambulance hurried upstairs. They lifted Dr. King onto a stretcher, then brought him down to the courtyard. I hurried after them. Andy Young and Ralph Abernathy did the same.

I had always been terrified of being exposed. Only once did I put such thoughts aside. When they put Dr. King into the ambulance, I instinctively began climbing in to go with him. Andy Young gently pulled me back. “No, Senator,” he said, “I don’t think you want to do that.”

A decision—perhaps not even consciously made—had placed me at the side of Martin Luther King Jr., the leader of the civil rights movement, on the day he died. Suddenly, the memory of our last telephone call accosted me. “Senator, please come to Memphis, I need you,” he had said. I had come, but it hadn’t helped. Nothing had.

Again the vision of his body flashed through my mind. I am descending into hell, I thought. I remembered all the preachers I had ever heard, describing the fiery furnaces of hell. I knew they were wrong; hell is not hot. Hell is cold.

As icy cold as I was now. Was I condemned to live forever shaking, unable to get warm, I wondered, while he lies colder still, in his grave? The thought was unbearable. I would gladly have suffered what I had feared for so long—public exposure and the threat to my political career—to have him here beside me now as he had been last night.

There were times I knew we were under surveillance by the FBI when we were together. Later, when I tried to get copies of any information the FBI had relating to me, it took four years of repeated requests before I received anything. Officials finally sent me fifty-five of the eighty-two pages in which my name was mentioned. I was unable to get any information about the time period of my involvement with Dr. King. The first entry on the papers I received was dated April 1968, after King’s death. Typed lines on about three-quarters of the pages I received were blacked out. The official explanation for the deletions was that the information was: (1) related solely to the internal personnel rules and practices of an agency, (2) could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy, or (3) could reasonably be expected to disclose the identity of a confidential source. I do not accept the FBI’s explanations.

Why am I telling all this now? If Dr. King had been an ordinary man, the telling of my story wouldn’t make much difference. However, Dr. King was no ordinary man. His life will be studied by scholars long after I’m gone.

Others have written about me, and the FBI has files relating to my life. Some published accounts differ from what I know to be the truth. In Carl Rowan’s book, Breaking the Barriers, he refers to a 1977 official Justice Department task force report which he said included what was purported to be Mrs. Georgia Davis’s account of what happened the night before King was killed. No one from a Justice Department task force ever interviewed me. I have not made any public statements about what happened until now.

In Ralph David Abernathy’s autobiography, And The Walls Came Tumbling Down, he refers to my relationship with King. I was surprised when I received a call from the Associated Press after Abernathy’s book was released. It had always been my constant fear that one of King’s close associates would talk about our relationship, but I couldn’t believe it was Ralph who had actually done it. Then, when I finally read the account, I was further discouraged that he had not told the whole truth. Ralph was King’s closest friend and confidant. Perhaps, due to his own illness and the toll the intervening years had taken on him, he was no longer able to remember things as they had happened.

When Dr. King’s life is researched, I want the part relating to me to be available in my own words. It is my own history as well, both the good and the bad.

I am writing my story now as honestly as I know how, because I am the only living person who knows exactly what happened.