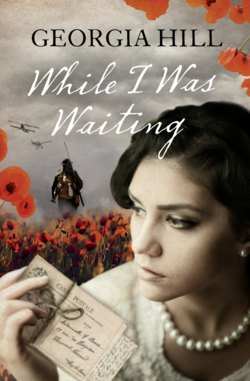

Читать книгу While I Was Waiting - Georgia Hill - Страница 7

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеApril 2000, Clematis Cottage, Stoke St Mary, Herefordshire

She was mad, they’d said. Utterly mad.

Rachel stood with her hands on her hips and surveyed her new home. Buying this little house was the only truly impulsive thing she had ever done. She swallowed; there was no going back. It was all hers now. Clematis Cottage belonged to her.

The house in question was tiny: little more than a two-up, two-down but pleasingly symmetrical, with windows flanking a satisfyingly solid red front door. A straight path led up through what must have once been an old-fashioned garden.

That was the good news.

It had been six months since Rachel had seen it last. She’d forgotten the ivy growing up the walls and across the windows – choking the brickwork and stealing the light. She’d forgotten the crazily dangling guttering. She’d forgotten the five-foot-high weeds obliterating the front garden.

She was mad, they’d said. Perhaps she was.

Rachel turned her back on the house and faced its view instead. This was what had sold it. The cottage stood on rising land, some way from the rest of the village of Stoke St Mary and could be reached only by a rutted track. The farmland behind sloped gently upwards, but in front of the house there was nothing but glorious open countryside.

The estate agent had said that spring was when Herefordshire was at its finest. Mr Foster had been a nice old boy, very different from the gelled-up-haired and shiny-suited types in London and she’d dismissed him as eccentric. She’d been wrong. She’d first seen the cottage in October and thought the landscape beautiful then, clothed in crimson and brown. But now, in early April, it was magnificent.

To her right she could see the baldy-smooth Brecon Beacons and beyond the jagged mountains of Wales loomed. Her eyes followed a sweep of hill to where the river valley sank and then rose again towards the east. Isolated houses were dotted about burnt-sienna fields, vast patches of a yellow so vivid it hurt her eyes interspersed ploughed fields and the apple orchards yet to blaze with blossom.

The furniture removers had finally gone. They’d backed the van, in a haze of dust and diesel fumes, down the track that led to the village and the outside world. Rachel felt her shoulders drop and exhaustion creep in. She turned back to scrutinise her new home once again. Behind it, the curving slopes of farmland seduced. Each field, green or red, was shining with fertile promise. Rachel tried not to look at the roof of the cottage; the choking moss and missing tiles were a symphony of neglect and future expense.

Was she mad? Her friends might yet be right. When she’d announced her decision to leave London and set up home in this tiny village in an isolated part of an isolated county they had forecast doom, gloom and a hasty retreat back to ‘civilisation’. No matter how much she tried to persuade them, they all thought it was a mistake.

A cottage?

In where?

On your own?

But Rachel was to be thirty soon. That’s when people made changes, she’d told them, made big, life-changing decisions. That her parents had announced their imminent departure to spend their retirement in the Algarve and had given her a lump sum in advance of her inheritance, had seemed like fate dealing her a hand. It had been the catalyst for change. She’d grown weary of London, anyway, and of the men who just wanted to play games and hurt her in the process. She wanted a simpler life; somewhere she could work uninterrupted. And maybe, just maybe, she would get the chance to become a new person – reinvent herself.

‘But won’t you miss all this?’ Best friend, Jyoti, gestured to the packed cocktail bar they were in. Rachel scanned the crowd. To her it looked full of men on the pull for another empty conquest. It made her queasy. She’d met Charles in a bar like this – and he’d screwed with her head and then cheated on her. If he was typical of London men, she was in no hurry to meet another.

She smiled at Jyoti over her margarita and thought hard before answering. When she’d moved to London as a student, she’d seen every play and gone to every exhibition and museum she could afford. Now she lived in a flat in the dusty suburbs of south-east London and rarely went to the West End. This was the first trip for ages. She simply didn’t feel the need any more.

‘I won’t be that far from Birmingham and I think there’s an arts centre in Ludlow – that’s only half an hour away and Malvern has some good pre-West End things on.’

‘But won’t you be lonely, sweet-pea? You’ll not even be in the actual village itself, will you?’ Kind-eyed Tim was concerned. Secretly so was Rachel, but with her small circle of friends coupling, moving abroad, having babies, Rachel was lonely now and too proud to admit it. She thought she might as well be lonely somewhere beautiful.

So she had sold her little London flat and bought Clematis Cottage. She had been shocked by what little her money would buy, even when it had been swollen by her parents’ gift. She was self-employed too, meaning that a bigger mortgage was difficult. Last year, she had been bumped up the steep track by a Mr Foster of Grant, Foster and Fitch Estate Agents to be shown Clematis Cottage. And she had fallen instantly, irrevocably in love. It had been the biggest decision she had ever made and it might be the biggest mistake. But she was determined to prove everyone wrong, including herself. With hands back on hips in a defiant gesture, she abandoned thinking and looked to the view that had been the deal-maker. She would make a success of this – she knew she would.

She thought back to kindly old Mr Foster’s words. When it had become apparent that she was seriously intent on buying the cottage, the comfortably rotund estate agent had seemed worried.

‘It’s an awful lot of work to be taking on, dear girl.’ He looked doubtfully at her high-heeled suede boots and thin jacket. ‘And with you being on your own. You’ll have a survey done, I expect?’

‘Erm, I don’t know,’ Rachel had said, feeling foolish, ‘It might put me off.’

Mr Foster gave her a steely look and sighed. ‘Here,’ he scribbled something on the back of his business card. ‘It’s the number of Mike Llewellyn. He’s a builder, but he’ll turn his hand to most things. He lives in the village and he knows the house. He’s not the cheapest, but he’s reliable and he does a good job.’

Rachel had thanked him and stored the card away in her bag. In the months since she’d last seen it, the cottage had taken on an unrealistically romantic air in her mind and she had forgotten just how much work it needed. She was glad she’d kept the number.

Brought back to the present by some crows flying overhead, cawing as they went, she closed her eyes and listened for a moment. Those who claimed that the countryside was silent were lying, but it was certainly peaceful. The air was full of sound. She could hear birds; she recognised a blackbird’s melodious tune, somewhere in the distance there was a tractor gearing up and nearer, the noisy lowing of cows. The wind got up and she could hear it making the trees on the hill behind the cottage shiver. It made a change from emergency sirens and the incessantly thumping bass from her London neighbour. The breeze lifted her hair and cooled her neck. She was glad; it had been a warm day to be moving house. All in all it had gone smoothly. True, she hadn’t got her washing machine plumbed in, she was without a landline and couldn’t coax the boiler into life, but the removal men had been hard-working, cheerful and nothing had been broken.

That she knew of.

They had been surprisingly good company, but she had wanted them gone long before the day was out. She flexed her tense shoulders, glad to be, at last, completely on her own.

Rachel tore herself away from the view and turned to explore her new home. As she did, she caught sight of a man striding up the rough track. To her intense irritation he stopped when he got to her and joined in her examination of the cottage.

‘You do need me. Mr Foster was right.’

Rachel stared at him. Her first impression was of gold and brown. He had longish hair, burnished treacle by the sun and tied back in an untidy ponytail. He was tall and lean with smoothly tanned skin and looked to be in his early twenties.

The man smiled and showed even white teeth. ‘Always said this place had the best view in the village. You could put up with a lot for that.’ He held out a long-fingered, capable-looking hand. ‘I’m Gabe Llewellyn. Mr Foster said you might be needing my services.’ His voice was deep and humorous and only slightly softened by a rural accent.

Rachel shook his hand warily. She was surprised to find it cool and dry and very firm. It was at odds with his grubby and sweaty-looking orange t-shirt. The name Llewellyn was familiar, though. ‘If I was expecting anyone, it would be a Mike Llewellyn.’ She was tired and it was an effort to speak. Wincing, she realised how rude she sounded.

Her tone didn’t seem to faze him. ‘That’s my Dad. He’s just finishing a job over Hereford way. Thought I’d come and take a quick look round, see what needs doing. Easier to see before you unpack your stuff.’ To her surprise, he seemed to pick up on her mood. ‘Sorry. Were you looking for a bit of peace and quiet? Long day when you’re moving, I reckon.’

Even though he was being surprisingly sensitive, Rachel couldn’t shift into politeness. ‘Yes it has been,’ she said stiffly. ‘What did you say your name was?’

‘Gabe.’ He suddenly looked defensive. ‘Short for Gabriel.’ When Rachel looked blank he explained further. ‘Mum had a bit of a Thomas Hardy thing going on, when she was pregnant. Just as well I was a boy. Would get a bit of stick down The Plough if I was called Bathsheba!’

Ridiculously, his knowledge of one of England’s greatest writers had the effect of reassuring Rachel. She relented – he probably wouldn’t take long after all. ‘I suppose you can come in,’ she said, aware that she still sounded churlish. Gabe looked at her hopefully. After a day spent with the removal men she knew the ropes. ‘I’ll put the kettle on, shall I?’

His grin widened and his brown eyes crinkled attractively. ‘Sweet. If I don’t have a look now, don’t know when I’ll get round to it. Busy time. Been working all day.’ He gestured to the sky. ‘Been making the most of the weather.’

It explained his scruffy appearance. And the faint whiff of masculine sweat.

‘I’ll just get the truck; I left it at the bottom of the track out of the way of Dave Firmin’s blokes. Dave’s been known to run into things.’ Gabe laughed. ‘I’ll have a look at that old boiler first. Been empty a while, this place. Pressure will have gone, I bet. You’ll need to get some oil delivered as well. Got some in the truck, though, which might see you through for the time being.’

Oh God, another thing to think about, but if he got the boiler working she could have a hot bath tonight. The idea of a long bubble bath made Rachel smile with relief. Gabe grinned again. He held her eyes for a moment and then swung round and, with an easy stride, loped back down the track to get his truck.

Gabe proved to be both thorough and relentless in his inspection of the cottage; another surprise, she had expected him to be neither. Two hours later he had got the boiler going and had disappeared into the attic to have a look at the inside of the roof.

Rachel made them both yet more tea and then, leaving him to it, unearthed a sweater and took her drink to sit out on the front step. She seemed to have been drinking tea all day and was sick of it, but it was a comfort of a sort.

Gabe eventually joined her. She’d left him investigating some possible damp. He sat beside her companionably and began totting up the estimate of work on the back of a tatty envelope. ‘I’ll get Dad to give you a proper costing in a few days, but this’ll give you an idea.’ When he handed it over she blanched.

‘Tell you what,’ Gabe said, when he saw her expression, ‘Some things don’t need doing straight away.’

Again, he seemed to have a knack of tapping into what she was thinking. It made her curious about him and she wondered what had caused him to be so sensitive to people’s moods.

‘The roof’ll need fixing, though,’ he went on, ‘that corner’s been letting in water for a good while, I reckon. But you don’t need to do everything at once and it’ll give you a chance to pay for things gradually too.’ He shrugged. ‘Dad and I can’t do most of the work immediately anyway, we’re booked up, so it’ll give you a chance to think it over. Oh,’ he said, as an afterthought, ‘I found this.’ He reached around behind him and handed her a large tin. ‘Found it in the attic, tucked behind the water tank and covered with a wasps’ nest.’

Rachel took the box from him. Once upon a time it must have held biscuits; she could just make out the name Huntley and Palmer underneath the rust. ‘What is it?’

‘I didn’t look inside.’ He drained his mug and began to gather his pen, tape measure and tools together.

It was getting late and Rachel shivered. The evening spring light had fooled her into thinking it was much earlier. Perversely, now Gabe was about to go, she wanted him to stay around. Stranger that he was, she was afraid of having to face up to her responsibilities alone. Wrestling her thoughts away from an expensive new roof, she turned all her attention to the tin in her lap. She smoothed a hand over its side – it felt cool and rough and snagged at her soft fingertips. With a struggle, she wrenched the lid off, cutting her thumb on a sharp edge in the process. ‘Damn,’ she cursed. She always took special care of her hands; they were her precious commodity.

To her surprise, Gabe took her hand in his and examined the wound. ‘You want to clean that up. You can get some nasty infections from rusty old metal, take it from me.’

He bent over her thumb. ‘Doesn’t look too bad, but make sure you treat it as soon as you can.’

She could feel his breath warm on her wrist. He was very near and an urge to run her fingers through his silky hair overcame her. Disconcerted, she snatched her hand out of his and then regretted it. Blaming it on tiredness, she pulled herself together and moved fractionally away from him.

‘So, is there anything in the tin?’ he asked cheerfully, shoving his stuff into his work belt. ‘Jewellery? Gold? Or just spiders?’ He laughed.

Rachel shuddered. ‘Don’t joke, I’ve got a thing about spiders.’

‘Would you like me to have a look first? I don’t mind them.’

‘Thank you,’ she smiled, ‘that’s really kind of you but it’s okay.’ She peered inside, almost afraid of what she might find. Taking a deep breath and sucking her injured thumb, she gingerly lifted out a package. It was heavy and wrapped in some dull, greasy material. She unpeeled a corner and something fell out. A postcard. ‘I think it’s a book and papers of some sort, postcards and things. Old, though. This one’s dated 1965.’ She held it to the light and read out the message: ‘Weather delightful, food excellent. Hotel pictured on front. All my love, P.’ Rachel flipped the postcard over and laughed. ‘Oh, it’s Brighton sea front. It hasn’t changed much.’

‘Wouldn’t know, never been,’ Gabe said absently, but his interest had obviously been sparked. He peered over her shoulder. ‘Who’s it to?’

‘Mrs H. Lewis, Clematis Cottage.’ Rachel looked at Gabe. ‘Oh it’s to here! To someone who lived here!’

Gabe smiled at her delight. ‘Yes, suppose it would be. There was a woman who lived here once. Think she was called Mrs Lewis. Lived here for years.’ He smoothed a lock of hair behind his ears. ‘Looks like you’ve found some of her stuff.’ He peered over her shoulder. ‘It’s fascinating, isn’t it? What else is in there?’

Rachel removed the rest of the fabric, the old smell making her nose prickle. She wasn’t sure she wanted to touch it but she wanted to get at what it was protecting.

‘It is a book,’ she cried and laid it in her lap. Opening the first few pages she saw it was a collection of writings, a few photographs, drawings, a few of which had been carefully stuck into the pages of the book. Rachel turned to the front page:

‘Henrietta Trenchard-Lewis, Her Life.’

she read off the frontispiece.

She looked thoughtfully at the postcard. ‘I ought to give it all back to her.’

‘Can’t, lovely, she died a few years back. She lived to a ripe old age, though.’

‘Oh, that’s sad.’

‘Sad? Oh I don’t know. I think she had a pretty long and full life. She was a right character, by all accounts. Used to give them what for at the home she ended up in. Had two husbands, bit of an old dragon I’ve been told. Terrorised the neighbourhood.’

Rachel looked at him curiously. ‘Did you know her?’

‘I vaguely remember a really old woman on a bicycle – that must have been her. Always wore black. I kept well clear of her.’ He grinned, boyishly. ‘I was scared of her, to be honest.’

‘Were there any children? Perhaps they’d like to have it. I know I would if it were my mother’s.’ Rachel began to leaf through the papers again. It seemed to be a barely begun scrapbook of sorts, with a mixture of an odd assortment of documents: pages cut from an exercise book, some closely covered with tiny handwriting, more postcards, a few faded sepia-tinted photographs. Then she found, slipped to the bottom of the tin, a bundle of letters tied with a faded velvet ribbon.

‘Don’t know. Mr Foster’ll know about that, probably. Who did you buy the place off, then?’ He rubbed a hand over his face in a weary gesture and stifled a yawn. ‘Sorry, it’s been a long day.’

‘A firm of solicitors. Brigsty and Smith.’

‘I know them. In Ludlow?’ He raised his brow at Rachel in enquiry and she nodded. ‘Well, they’ll know what you do with it.’ He glanced at his watch – an expensive one, glistening on a very suntanned arm. As he raised his hand the golden hairs on his sinewy forearm caught the light from the late-evening sun. ‘Better be off. Way past opening time and the first pint isn’t gonna touch the sides. I’ll be round next week with the job spec and I’ll fix up a date to see to the roof.’ He rose to his feet to go, but hesitated and looked down at her. Perhaps he sensed her loneliness. ‘Do you, erm, do you want to come down the pub? It’s a nice friendly crowd. Meet some of your new neighbours.’

Rachel shook her head. ‘No, too tired. Off to have a long soak in some very hot water, thanks to you. Thank you so much for all you’ve done, Gabe.’ She smiled up at him with genuine gratitude for the first time. Their eyes met and a frisson of something, some expectation, passed between them.

He gave her an odd look. ‘No probs. Are you going to be, you know, alright on your own?’

She nodded. ‘I’ll be fine. Thank you.’

‘See you, then. Oh, and don’t forget to see to that cut.’ With that, he swung himself into his pick-up, this year’s registration, she noticed. He and his father must be doing well. And with a wave and a cloud of dust he skidded down the track.

Rachel stared after the Toyota for some time. An intriguing man. And kind. Even though he’d had a long day and was obviously tired, he’d gone out of his way to help. Unsophisticated, yes, but incredibly sensitive and thoughtful. Honest too. No game-playing there. She’d never met anyone quite like him before.

She blew out a long breath. At last she was on her own. But, somehow, now she had what she thought she wanted, the weight of her alone-ness was oppressive. Rising stiffly, she turned her back on the promise of a glorious sunset to go into the house.

‘You’ll be happy here. I was.’

The voice had her whirling around again, heart thumping. No one there. Standing frozen, Rachel listened. Nothing. She shook her head. Must have been the wind in the trees. On edge and blaming tiredness, she went into the house.

She put the tin in the kitchen. She didn’t want to look through the contents tonight. It didn’t feel right somehow, not when it might belong to someone else. And besides, she had other more pressing things to do.