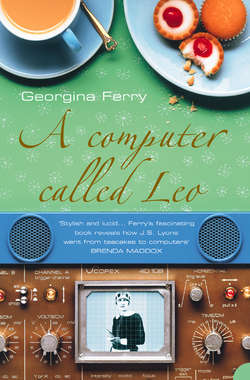

Читать книгу A Computer Called LEO: Lyons Tea Shops and the world’s first office computer - Georgina Ferry - Страница 5

1 A Mission to Manage

ОглавлениеThe clatter of machinery was relentless. Light fell through the high windows on row after row of workers, bent to their identical tasks; but this was no factory. This was the Checking Department of J. Lyons & Co. at Cadby Hall in West London, part of the vast clerical infrastructure that underpinned the operation of Britain’s largest food empire in its mid-1930s heyday. Seated at their desks in ruler-straight rows, the clerks tapped away at their Burroughs mechanical calculators, separated from one another by partitions erected to reduce distraction. The adding machines, solid constructions of steel and varnished wood, had up to a dozen columns of numbered keys to input the figures, and a crank on the side to sum the totals. Like a cash register, they printed out a record of the calculation on a roll of paper.

The three hundred clerks in the department, most of them girls not long out of school, had but a single job to do: to add up the totals on the waitresses’ bills from the two hundred and fifty-odd high street teashops run by Lyons, and to check them against the cash takings banked by the shops. A squad of office boys kept them supplied with sets of bills, received from the teashops that morning in locked leather bags and sorted into numerical and alphabetical order by the office juniors. The senior clerks and managers, invariably male, stalked the aisles between the desks in their sombre suits, ensuring that every fashionably waved head was bent to its task; it would be their duty to follow up any discrepancies revealed as the streams of numbers gradually unrolled.

The Checking Department was one of three central offices at Lyons supervised in those pre-war days by a young manager called John Simmons. Yet as Simmons surveyed the roomful of clerks and their clacking machines, all he saw was a waste of human intelligence. Punching a Burroughs calculator could be worse drudgery even than unskilled factory work for the girls who made up most of the workforce. At least on an assembly line, he mused, you could chat to the next worker or let your mind wander while you carried out a repetitive task. Mechanised clerical work demanded total attention, but granted no intellectual satisfaction in return. Simmons began to dream of the day when ‘machines would be invented which would be capable of doing all this work automatically’. Such machines would free managers such as himself from marshalling their armies of clerks, and allow them ‘to examine the figures, to digest them, and to learn from them what they had to tell us of better ways to conduct the company’s business’.

Within little more than a decade he had made that dream a reality by persuading the board of Lyons that their company must become the first in the world to build its own electronic, digital computer. This was not, as computer historian Martin Campbell-Kelly has written, merely ‘the whim of a highly-placed executive’. While occasionally unrealistic, perhaps even grandiose in his conceptions, Simmons was not a man subject to ill-considered whims. From his perspective, building a computer was not only logical and rational but essential to the good of Lyons and the efficiency of British business. Moreover, his idealism was not out of place in the Lyons corporate culture. Far from being surprising that the seed of business computing should take root and grow in Lyons before any other company in the world, in almost every respect it provided ideal conditions.