Читать книгу Fire Ants and Other Stories - Gerald Duff - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFire Ants

She had kept the bottle stuck down inside a basket of clothes that needed ironing, and throughout the course of the day whenever she had a chance to walk through the back room where the basket was kept, she would stop for the odd sip or two. By the middle of the afternoon, she had stopped feeling the heat even though she had cooked three coconut pies, one for B. J.’s supper and two for the graveyard working, and had ironed dresses for her and Myrtle. And by suppertime with Myrtle and B. J. and Bubba and Barney Lee Richards all around the table waiting for her to bring in the dishes from the kitchen, MayBelle had reached the point that she couldn’t tell if she had put salt in the black-eyed peas or not even when she tasted them twice, a whole spoonful each time.

“Aunt MayBelle,” B. J. was saying, looking up at her with a big grin on his face, “where’s that good cornbread? I bet old Barney Lee could eat some of that.” He reached over and punched at one of Barney Lee’s sides where it hid his belt. “He looks hungry to me, this boy does.”

“Aw, B. J.,” said Barney Lee and hitched a little in his chair. “I shouldn’t be eating at all, but I save up just enough to eat over here at your Mama’s house.”

“Well, you’re always welcome,” said Myrtle from the end of the table by the china cabinet. “We don’t see enough of you around here. Used to, you boys were always underfoot. I wish it was that way now.”

“Barney Lee,” said MayBelle, and waited to hear what she was going to say, “your hair is going back real far on both sides of your head. Not as far as B. J.’s, but it’s getting on back there all right.” She moved over and set the pan of hot cornbread on a pad in the middle of the table. “You gonna be as bald as your old daddy in a few years.”

MayBelle straightened up to go back to the kitchen for another dish, and the Bear-King winked at her and lifted a paw, making her not listen to what Myrtle was calling to her as she walked through the door of the dining room. Maybe I better go look at that clothes basket before I bring in that bowl of okra, she thought to herself, and made a little detour off the kitchen. The foreign bottle was safe where she had left it, and she adjusted the level of the vodka inside to where it came just to the neckline of the white bear on the label.

When she came back into the dining room with the okra, everybody was waiting for B. J. to say grace, sitting quiet at the table and cutting eyes at the pastor at the head of it. “Sit down for a minute, Aunt MayBelle,” B. J. said in a composed voice and caught at her arm. “Let’s thank the Lord and then you can finish serving the table.”

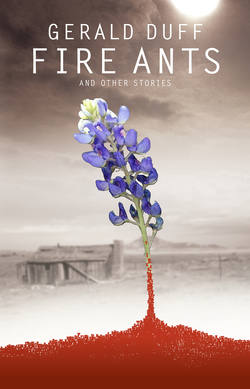

MayBelle dropped into her chair and looked at a flower in the middle of the plate in front of her. It was pounding like a heart beating, and it did so in perfect time to the song of a mockingbird calling outside the window. It’s the Texas State Bird, she thought, and Austin is the State Capital. The native bluebonnet is the State Flower and grows wild along the highways every spring. But it’s hard to transplant, and it smells just like a weed. If you got some on your hands, you can wash and wash them with heavy soap, and the smell will still be there for up to a week after. But they are pretty to look at, all the bluebonnets alongside the highway. There were big banks of them on both sides of the dirt road for as far as you could see, and when the car went by them it made enough wind to show the undersides of the flowers, lighter blue than the tops of the petals.

He stopped the car so they could look at all of them on both sides of the road, and a little breeze came up just when he turned the engine off, and it went across the bluebonnets like a wave. It was like ripples in a pond; they all turned together in rings and the light blue traveled along the tops of the darker blue petals as if it wasn’t just the west wind moving things around, but something else all by itself.

He asked her if she didn’t think it was the prettiest thing she ever saw, and she said yes and turned in the seat to face him. And that’s when he reached out his hand and put it on the back of her head and said her eyes put him in mind of the color on the underside of the bluebonnets, and he had always wanted to tell her that. It was hot, early May, and there was a little line of sweat on his upper lip and when he came toward her she watched that until her eyes couldn’t focus on it anymore he was so close and then his mouth was on hers and it was open and there was a little smell of cigarette smoke.

She could hear the hot metal of the car ticking in the sun. It was hers, the only one she ever owned, and that was only for a little over a year. It set high off the road and could go over deep ruts and not get stuck and it could climb any hill in Coushatta County without having to shift gears. The breeze was coming in the car window off the bluebonnets and it felt cool, but his hands were hot wherever they touched her and she kept her eyes closed and could still see the light blue underside of the flowers and the thin line of sweat on his lip and she was ticking all over just like the new car sitting still between the banks of bluebonnets in the sun.

“All this we ask in Thy Name, Amen,” said B. J. and reached for the plate of cornbread. “You can go get the mashed potatoes now, Aunt MayBelle.”

“Yes,” said Myrtle, looking across the table at her, “and another thing too while you’re in the kitchen. You poured me sweet milk in my glass, and you know I’ve got to have clabbermilk at supper.”

Everybody allowed as how the vegetables were real good for this late in the season, but that the blackberry cobbler was a little tart. It was probably because of the dry spell, Barney Lee said, and they all agreed that the wild berries had been hard hit this year and might not even make at all next summer unless they got some relief.

After supper Myrtle and Barney Lee went into the living room to catch the evening news on the Dumont, and B. J. put on his quilted suit and went out with Bubba and the cattle-prod to agitate the Dobermans and German shepherds.

From where she stood by the sinkful of dishes, MayBelle could hear the dogs begin barking and growling as soon as they saw B. J. and Bubba coming toward the pen. She ran some more water into the sink, hot enough to turn her hands red when she reached into it, and she almost let it overflow before she turned off the faucet and started washing. She didn’t break but one dish, the flowered plate off which she had eaten a little okra and a few crowder peas at supper, but dropping it didn’t seem to help the way she felt any.

She stood looking down at the parts it had cracked into on the floor, feeling the heat from the soapy water rising into her chest and face and hearing the TV set booming two rooms away, and decided she would look into the clothes basket again as soon as she had finished in the kitchen.

Outside a dog yipped and Bubba laughed, and MayBelle lifted her eyes to the window over the sink. The back pasture was catching the last rays of the setting sun, and it looked almost gold in the light. But when she looked closer, she could see that the yellow color was in the weeds and sawgrass itself, not just borrowed from the sun, and what looked like haze was really the dry seed pods rattling at the ends of the stalks.

Further up the hill yellowish smoke was rising from one of the cabins in the quarter, perfectly straight up into the sky as far as she could see, not a waver or a bit of motion to it. She stood watching it for a long time, dishcloth in one hand and a soapy glass in the other, until finally her eye was caught by a small figure moving slowly across the back edge of the pasture and disappearing into the dark line of pines that enclosed it.

That’s old Sully, she said to herself, probably picking up kindling or looking at a rabbit trap. Wonder how he stands the heat of a wood cookstove this time of the year. Keeps it going all the time, too, Cora says.

In the living room Barney Lee asked Myrtle something, and she answered him, not loud enough to be understood, and MayBelle went back to the dishwashing, rinsing and setting aside the glass she was holding. It had a wide striped design on it, and it felt right in her hand as she set it on the drainboard to dry.

Picking up speed, she finished the rest of the glassware, the knives and forks, the cooking pots and the cornbread skillet, and then wiped the counters dry and swabbed off the top of the gas stove. By the time she finished turning the coffee pot upside down on the counter next to the sink, the striped glass on the drainboard had dried and a new program had started on the television set. The sounds of a happy bunch of people laughing and clapping their hands came from the front part of the house as MayBelle picked up her glass and walked out of the kitchen toward the back room.

She filled the glass up to the top of where the colored stripe began and took two small sips of the clear bitter liquid. She stopped, held the foreign bottle up to the light and watched the Bear-King while she drained the rest of the glass in one long swallow. A little of the vodka got up her nose, and she almost sneezed but managed to hold it back, belching deeply to keep things balanced. As she did, the Bear-King nodded his head, causing a sparkle of light to flash from his crown, and lifted one paw a fraction. “Thank you, Mr. Communist,” MayBelle said, “I believe I will.”

A few minutes later, Bubba looked up from helping B. J. untangle one of the German shepherds which had got a front foot hung in the wire noose on the end of the cattle-prod, barely avoiding getting a hand slashed as he did, and caught sight of something moving down the hill in the back pasture. But by the time he got around to looking again, after getting the dog loose and back in the pen and the gate slammed shut, whatever it was had got too far off to see through his sweated-up glasses.

“B. J.,” he said and waved toward the back of the house, “was that Aunt MayBelle yonder in the pasture?”

“Where?” said B. J. in a cross voice through the Johnny Bench catcher’s mask. He laid the electric prod down in the dust of the yard and pulled the suit away from his neck so he could blow down his collar. He felt hot enough in the outfit to faint, and the dust kicked up by the last dog had got all up in his face mask, mixing with the sweat and leaving muddy tracks at the corners of his cheeks. “What would she be doing in that weed patch? She’s in the house last I notice.”

“Aw, nothing,” said Bubba. “If it was her, she just checking out the blackberries, I reckon. It don’t make no difference.”

“Bubba,” said B. J. and paused to get his breath and look at the pen of barking dogs in front of him. “I believe Christian Guard Dogs, Incorporated, has made some real progress in the last few days. Look at them fighting and snapping in there. Why, they’d tear a prowler all to pieces in less than two minutes.”

“B. J.,” Bubba answered, “watch this.” He picked up the dead pine limb and rattled the hog wire with it, and immediately the nearest Doberman lunged at the fence, snapping and foaming at the steel wire between its teeth, its eyes narrow and bloodshot.

“That dog there,” Bubba announced in a serious flat voice, “would kill a stray nigger or a doped-up hippie in a New York minute.”

“I figure you got to do what you can,” said B. J., “and if there’s a little honest profit in it for a Christian, it’s nothing wrong with that.” B. J. took off the catcher’s mask and stood for a minute watching the worked-up dogs prowl up and down the pen, baring their teeth at each other as they passed, their tails carried low between their legs and the hair on their backs all roughed up. Then he turned toward his brother and clapped him on the shoulder.

“Let’s go get a drink of water and talk about your business problems, Bubba. The Lord’ll find an answer for you. You just got to give Him a chance.”

The houses were lined up on each side of a dirt road that came up from the patch of weeds to the south and stopped abruptly at the edge of the pasture. In front of the first one on the left, a cabin with two front doors opening into the same room and a window in between them with a pane of unbroken glass still in it, was the body of a ’54 Chevrolet up on blocks. All four wheels had been taken off a long time ago and fastened together with a length of log chain and hung from the lowest limb of an oak tree. The bark on the oak had grown over and around the chain, and the metal of the wheels had fused together with rust.

MayBelle took another sip straight from the bottle and stepped around a marooned two-wheeled tricycle, grown up in bitter weeds, careful not to trip herself up. She walked up on the porch of the next shotgun house and leaned over to peer through a knocked-out window. Her footsteps on the floorboards sounded like a drum, she noticed, and she hopped up and down a couple of times to hear the low boom again. There was enough vodka left in the bottle to slosh around as she did so, and she shook it in her right hand until it foamed. It didn’t seem to bother the Bear-King any.

The only thing left in the front room was a two-legged wood stove tilted over to one side and three walls covered with pictures of movie stars, politicians, and baseball players. “Howdy, Mr. and Mrs. President,” MayBelle said to a large photograph of JFK and Jackie next to a picture of Willie Mays and just below one of Bob Hope. “How y’all this evening?” She took another little sip and had a hard time getting the top screwed back on, and by the time she had it down tight, it was getting too difficult in the fading light to distinguish one face on the wall from another, so she quit trying.

The back of the next cabin had been completely torn off, so when MayBelle stepped up on the porch and looked through the door all she could see was a framed scene of the dark woods behind. A whip-poor-will called from somewhere deep inside the picture, and after a minute was answered by another one further off. MayBelle held her breath to listen, but neither bird made another sound, and after a time, she stepped back down to the road and looked at the clear space around her.

She felt as though it was getting dark too quickly and she hadn’t been able to see all she wanted. Already the tops of the bank of pines around the row of houses were vanishing into the sky, and one by one the features of everything around her, the stones in the road and the discarded jars and tin cans, the bits and pieces of old automobiles, the broken furniture lying around the porches and the shiny things tacked up on the wall and around the edges of the eaves, were slipping away as the light steadily diminished. Whatever it was she had come to see, she hadn’t discovered yet, and she shivered a little, hot as it was, feeling the need to move on until she found it. I waited too late in the day again, she thought, and now I can’t see anything.

It was like the time at Holly Springs she had been playing in the loft of the barn with some of the Stutts girls and had slipped down between the beams and the shingles of the roof to hide. Papa had found her there at supper time, passed out from the sting of wasps whose nest she had laid her head against, her face covered with bumps and her eyes swollen shut from the poison. He had carried her down to Double Pen Creek, the coldest water in the county, running with her in his arms two miles through the cotton fields and the second-growth thickets until he was able to lay her in the water and draw off the fire of the wasp stings. She hadn’t been able to see for six days after that, even after the swelling went down and she was able to open her eyes finally. The feeling of the light fading and the dark creeping up came on her again as she stood in the road between the rows of ruined houses, the bottle tight in her hand.

“You looking for Cora, her place down yonder.”

MayBelle lifted her gaze from the Bear-King and focused in the direction from where the voice had come. In a few seconds she picked him out of the shadow at the base of a sycamore trunk two houses down. He was a little black man in a long coat that dragged the ground and his hair was as white as cotton.

“You Sully,” declared MayBelle and took a drink from her quart bottle.

“Yes, ma’am,” said the little black man and giggled high up through his nose. “That be me. Old Sully.”

“You used to do a little work for Burton Shackleford. Down yonder.” She waved the bottle off to the side without looking away from the sycamore shadow.

“That’s right,” he called out in a high voice to the empty houses, looking from one side of the open space to the other and then taking a couple of steps out into the road. “You talking about me, all right. I shore used to do a little work for Mister Burton. Build some fence. Dig them foundations. Pick up pecans oncet in a while.”

“Uh-huh,” said MayBelle and paused for a minute. Two whip-poor-wills behind the backless house traded calls again, further away this time than before.

“I heard a lot about you. Cora she told me.”

“Say she did?” said Sully and kicked at something in the dust of the road. “Cora you say?”

“That’s right,” MayBelle said, addressing herself to the Bear-King and lifting the bottle to her mouth. The liquor had stopped tasting a while back and now seemed like nothing more than water.

“She says,” MayBelle said and paused to pat at her lips with the tips of her fingers, “Cora says you’re still a creeper.”

“She say that?” Sully asked in an amazed voice and scratched at the cotton on top of his head. “That’s a mystery to me. She a old woman. Last old woman in the quarter.” He stopped and looked off at the tree line, then down at whatever he had kicked at in the sand and finally at the bottle in MayBelle’s hand.

“What that is?” he said.

MayBelle raised the bottle to eye level and shook its contents back and forth against the Bear-King’s feet, “That there liquor is Communist whiskey.”

Then both regarded the bottle for a minute without saying anything as the liquid moved from one side to the other more and more slowly until it finally settled to dead level in MayBelle’s steady grasp.

“Say it is?” Sully finally said after a while.

“Uh-huh. You ever drink any of this Communist whiskey?”

“No ma’am, Miz MayBelle. I a Baptist,” Sully said. “If I’s to vote, I vote that straight Democrat ticket.”

MayBelle unscrewed the lid, took a hard look at the level of the side of the bottle, and then carefully sipped until she had brought the liquid down to where the Bear-King appeared to be barely walking on the water beneath his feet.

“You don’t drink nothing then,” she said to Sully, carefully replacing the metal cap and giving it a pat.

“Nothing Communist, no ma’am, but I do like to sip a little of that white liquor that Rufus boy bring me now and again. Somebody over yonder in Leggett or Marston, they makes that stuff.”

“Is it hot?”

“Is it hot?” declared Sully. “Sometimes I gots to sit down to drink from that Mason jar.”

“Tell you what, Sully,” said MayBelle and gave the little black man a long look over the neck of the bottle.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said and straightened to attention until just the edges of his coat were touching the dust of the road. “What’s that?”

“You go get yourself a clean glass and bring me one too, and I’ll let you have a taste of this Communist whiskey.” Sully spun around to leave and she called after him: “You got any of that Mason jar, bring it on, too.”

“It be here directly,” Sully answered over his shoulder and hopped over a discarded table leg in his way.

MayBelle walked over to the nearest porch and sat down to wait, her feet stuck straight out in front of her, and began trying to imitate the whip-poor-will’s call, sending her voice forth into the darkness in a low quavering tone, but not a bird had answered, no matter how she listened, by the time Sully got back with two jelly glasses and a Mason jar full of yellow shine, the sheen and consistency of light oil.

“You gone fell down again in amongst all the weeds, Miz MayBelle,” Sully said, “you keep on trying to skip.”

“I have always loved to skip,” said MayBelle, moving through the pasture down the hill at a pretty good clip. She caught one foot on something in the dark and stepped high with the other one, bobbing to one side like a boxer in the ring.

“Watch me now,” she said. “Yessir. Goddamn.”

“You sho’ do cuss a lot for a white lady,” said Sully, dodging and weaving through the rank saw-grass and bull nettles.

“I know it. Damn. Hell. Shit-fart.”

“Uh-huh,” said Sully, hurrying to catch up and trying to see how far they had reached in the Shackleford back pasture. The moon was down, and he was having a hard time judging the distance to the stile over the back fence, what with his coat catching on weeds and sticks and the yellow shine thundering in his head.

He bent down to free his hem from something that had snagged it, felt the burn of bullnettle across his hand, and recognized a clump of trees against the line of the night sky.

“I’se you,” he called ahead in a high whisper. “I’d keep to the left right around here. Them old fire ants’ bed just over yonder.”

“Where?” said MayBelle, stopping in the middle of a skip so abruptly that she slipped on something which turned under her foot and almost caused her to fall. “Where are them little boogers?”

“Just over yonder about fifteen, twenty feet,” Sully said, glad to stop and take a deep breath to settle the moving shapes around him. “See where them weeds stick up, look like a old cowboy’s hat? Them ants got they old dirt nest just this side.” He paused to smooth his coat around him and rub his bullnettle burn. “That there where they sleep when they ain’t out killing things.”

“You say they tough,” said the skinny white lady. “It burns when they bite?”

“Burns? Lawdy have mercy. Do it burn when they bites? Everywhere one of them fire ants sting you it’s a little piece of your hide swell up and rot out all around it. Take about a week to happen.”

Sully felt the ground begin to tilt to one side, and he lifted one foot and brought it down sharply to level things out. The earth pushed back hard, but by keeping his knee locked, he was able to hold it steady. “I don’t know how long I can last,” he said to his right leg, “but I do what I can.”

“Shit, goddamn,” said MayBelle, “let’s go see if they’re all asleep in their bed.”

“You mean them fire ants? They kill the baby birds and little rabbits in they nests. Chop ’em up, take ’em home and eat ’em. I don’t want no part of them boogers. I ain’t lost nothing in them fire ants’ bed.”

“Well, I believe I did,” said MayBelle. “Piss damn. I’m going to go over there and go to bed with them.”

Sully heard the dry weeds crack and pop as the white lady began moving toward the cowboy hat shape, and he lifted his foot to step toward the sound. When he did, the released earth flew up and hit him all down the right side of his body and against his ear and jaw. “I knowed it was going to happen,” he said to his right leg as he lay, half-stunned in the high weeds, “I let things go too quick.”

By the time he was able to get up again, scrambling to first one knee, then the other, and then flapping his arms about him to get all the way off the ground and away from its terrible grip, the skinny white lady had already reached the fire ant bed and dropped down beside it. Sully moved at an angle, one arm much higher than the other and his ears ringing with the lick the ground had just given him, until he came up close enough to see the dark bulk of the old woman stretched out in the soft mound of ant-chewed earth.

“You got to get up from there, Miz MayBelle,” he said and began to lean toward her, hand outstretched, but then thought better of it as he felt the earth begin to gather itself for another go at him.

She was speaking in a crooning voice to the ant bed, saying words he couldn’t understand and moving herself slowly from side to side as she settled into it.

“Miz MayBelle,” Sully said, “crawl on up out of there now. They gonna eat you alive lying there. That ain’t no fun.”

“Don’t you put a hand on me, Papa,” she said in a clear hard voice, suddenly getting still, “I’m right where I want to be.”

“I see I got it to do,” Sully said and threw his head back to look around for somebody. He couldn’t see a soul, and every star in the night sky was perfectly clear and still.

“You decide to get up while I’m gone,” he said to the dark shape at his feet, “just go on ahead and do it.”

Running in a half-crouch with one arm out for balance against the tilt the earth was putting on him, Sully started down the hill toward the back fence of the Shackleford place, proceeding through the weeds and brambles like a sailboat tacking into the wind. About every fifty feet, he had to lean into a new angle and cut back to keep the ground from reaching up and slamming him another lick, and the dirt of the dry field and the hard edges of the saw-grass were working together like a charm to slow and trip him up.

He went over the stile on his hands and knees, and the earth popped him a good one again on the other side of the fence, but he was able to get himself up by leaning his back against the trunk of a pine tree and pushing himself up in stages. There was a dim yellow light coming from a cloth tent right at the back steps of the house, and Sully aimed for that and the sounds of a man’s voice coming from it in a regular singing pattern. He got there in three more angled runs, the last one involving a low clothesline that caught him in the head just where his hairline started, and he stopped about ten feet from the tent flap, dust rising around him and the earth pushing up hard against one foot and sucking down at the other one.

Barney Lee Richards lifted the tent flap and stuck his head out to see what had caused all the commotion in the middle of B. J.’s prayer against the unpardonable sin, but at first all he could make out was a cloud of suspended dust with a large dark shape in the middle of it. He blinked his eyes, focused again, and the form began to resolve itself into somebody or something standing at an angle, an arm extended above its head, which looked whiter than anything around it, and the whole thing wrapped in a long hanging garment. The clothesline was making a strange humming sound.

“Aw naw,” he said in a choked disbelieving voice, jerked his head back inside the lighted tent, and spun around to look at B. J., his eyes opened wide enough to show white all around them.

“B. J.,” he said, “it’s something all black wearing an old long cape and it’s got white on its head and it’s pointing its hand up at the sky.

“At the sky?” said B. J. and began to fumble around in the darkness of the tent floor with both hands for his Bible. “You say it’s wearing a long cape?”

“That’s right, that’s right,” said Barney Lee in a high whine and began to cry. He heaved himself forward onto his hands and knees and lurched into a rapid crawl as if he were planning to tear out the back of the mountaineer’s tent, colliding with B. J. and causing him to lose his grip on the Bible he had just found next to a paper sack full of bananas.

“Hold still, Barney Lee,” B. J. said. “Stop it now. I’m trying to get hold of something to help us if you’ll just set still and let me.”

To Sully on the outside, standing breathless and stunned next to the clothesline pole, the commotion in the two-man tent made it look as though the shelter was full of a small pack of hounds fighting over a possum. First one wall, then the other bulged and stretched, and the ropes fastened to the tent stakes groaned and popped under the pressure. The stakes themselves seemed to shift and glow in the dark as he watched.

“White folks,” Sully said in a weak voice and then, getting a good breath, “white folks. I gots to talk to you.”

The canvas of the tent suddenly stopped surging, and everything became quiet. Sully stood tilted to one side and braced against the pull of the earth, his mouth half open to listen, but all he could hear for fully a minute was the sound of the yellow shine seeping and sliding through his head and from far off somewhere in the woods the call of a roosting bird that had waked up in the night.

Finally the front flap of the tent opened up a few inches and the bulk of a man’s head appeared in the crack.

“Who’s that out there?” the head asked.

“Hidy, white folks,” said Sully. “It’s only just me. Old Sully. Just only an ordinary old field nigger. Done retire.”

The flap moved all the way open, and B. J. crawled halfway out the tent, straining to get a better look.

“It’s just an old colored gentleman, Brother B. Lee,” he said over his shoulder. “Like I told you, it ain’t nothing to worry about.”

“Well,” said Barney Lee from the darkness behind him, “I was afraid it was something spiritual. Why was it standing that way with its hand pointing up, if it was a colored man?”

“Hello, old man,” said B. J., all the way out of the tent now and standing up to brush the dirt off his pants. “Kinda late at night to be calling, idn’t it?”

“Yessir,” said Sully. “It do be late, but a old man he don’t sleep much. He don’t need what he use to.”

“Uh-huh,” B. J. said and turned back to help Barney Lee who had climbed halfway up but had gotten stuck with one knee bent and the other leg fully extended.

“Why,” Barney Lee addressed the man in the long coat, “Why you standing that way with your arm sticking way up like that?”

“Well sir,” said Sully and turned his head to look up along his sleeve. “It seem like it help me to stand like this.” The shine made a ripple in a new little path in his head, and he had to lift his hand higher to keep things whole and steady.

“I just wish you’d listen to that, Barney Lee,” B. J. said in a tight voice.

“What? I don’t hear nothing.”

“That’s exactly what I’m talking about. Here’s this old nig—colored gentleman—come walking up in the dead of night, and what do you hear from them dogs? Not a thing.”

Everybody stopped to listen and had to agree that the dog pen was showing no sign of alert.

“And I thought the training was going along so good the last few days. I’m getting real discouraged about Christian Guard Dogs.” B. J. sighed deeply, kicked at the ground, and coughed at the dust hanging in the air. “I don’t know. I just don’t know.”

“However,” said Sully, “what it is I come up here and bother you white folks about it be up yonder in the pasture.” He swung a hand back in the direction he had come, almost lost the hold he was maintaining against the steady pull of the earth, and staggered a step or two before he found it again.

“Say it helps you to stand like that?” asked Barney Lee and shyly stuck one arm above his head until it pointed in the direction of the Little Dipper. “Reckon it helps circulation or something?”

“Didn’t make one peep,” said B. J. “I didn’t hear bark one, much less a growl.”

“Yessir, white folks, it up yonder in the pasture. What I come here to your pulp tent for.” Sully’s arm was getting heavy so he ventured to lean against the pole supporting the clothesline and found that helped him some. Things were tilted, but not moving.

“A few minute ago, I was outside my house walking to that patch of cane. You know, tending to my business and that’s when I heard her yonder.”

“Who?” said B. J., making conversation as he looked over at the dark outline of the Christian Guard Dog pen as though he could see each individual Doberman and shepherd.

“Miz MayBelle.”

“MayBelle? Aunt MayBelle Holt?” B. J. turned back to look at the little black man leaned up against the pole. “You say you heard her up in the nigger quarters?”

“Naw sir, white folks, not rightly in the quarters. She in that back pasture lying down in that fire ant bed.”

“The fire ant bed?”

“Yessir, old Sully was in the quarters and she in the bed of fire ants.”

“What’s Aunt MayBelle doing in the fire ant bed? Did she fall into there?”

“I don’t know about that,” said Sully and adjusted his pointing arm more precisely with relation to the night sky. “I only just seed her in there a talking to them boosters.”

“Come on, Brother B. Lee,” B. J. said and broke into a trot toward the back fence. “We got to see what’s going on. Them things will eat her up.”

“Thata’s just the very thing I thought,” said Sully, lurching away from the clothesline pole, and stumbling into a run after B. J., his gesturing right arm the only thing keeping him away from another solid lick from the ground. “I thought it sure wasn’t no good idea for a white lady to lie down in amongst all them biting things.”

“I’m coming, B. J.,” called Barney Lee, a few steps behind Sully but close enough that the old man’s flapping coat-tail sent puffs of dust up into his face. As he ran through the fence at the bottom of the hill, he raised an arm above his head and immediately felt his wind get better and his speed increase a step or two.

“I believe,” Barney Lee said between breaths to the tilted sidling figure moving ahead of him, “that it’s doing me good, too. Pointing my arm up at the sky like this.”

“Yessir, white folks,” Sully said to the words coming from behind him, fighting as best he could against the yearn of the earth beneath his feet. It was going to get him at the stile again, he knew, but he had to live with that fact. I just get them fat white folks to the ant bed, I quit, he said to the clouds of dust floating up before him. You can have all of it then. I give it on up. He ran on, changing to a new tack every few feet, the pointing arm dead in the air above him, and listened to the shine rumble and slide through all the crannies of his head.

“It’s gonna be hard times in the morning,” he said out loud and aimed at the fence stile coming up. It most always is.

You’ve got to say something to me, she said. You don’t talk to me right. Now you got to say something to me.

I’m talking to you, he said. I’m talking right now to you. What you want me to say? This?

And he did a thing that made her eyes close and the itching start in her feet and begin to move up the back of her legs and across her belly and along her sides down each rib. Oh, she said, it’s all in my shoulders and the back of my neck.

She let him push her further back until her head touched the green and gold bedspread, and one of her hands slipped off his shoulder and fell beside her as though she had lost all the strength in that part of her body. The arm was numb, but tingling like it did in the morning sometimes when she had slept wrong on it and cut off the circulation of blood. She tried to lift it and something like warm air ran up and down the inside of her upper arm and settled in her armpit under the bunched-up sleeve of the dress.

No, she said, it’s hot and I’m sweating. It’s going to get all over her bed. It’ll make a wet mark, and it won’t dry and she’ll see it.

He said no and mumbled something else into the side of her throat that she couldn’t hear. Something was happening to the bottoms of her feet and the palms of her hands. It was crawling and picking lightly at the skin. Just pulling it up a little at a time and letting it fall back and doing it over again until it felt like little hairs were raising up in their places and settling back over and over.

Talk to me, she said into his mouth. Say some things to me. You never have said a thing yet to me.

I’ll say something to you, he said, and moved against her in a way that caused her to want to try to touch each corner of the bed.

If I put one foot at the edge down there and the other one at the other corner and then my hands way out until I can touch where the mattress comes to a point, then if somebody was way up above us and could look down just at me and the way I’m laying here, it would look like two straight lines crossing in the middle. That makes an X when two lines cross. And in the middle where they cross is where I am.

Please, she said to the little burning spots that were beginning to start at each end of the leg of the X and to move slowly towards the intersection, come reach each other. Meet in the middle where I am.

But the little points of fire, like sparks that popped out of the fireplace and made burn marks on the floor, were taking their own time, stopping at one place for a while and settling there as if they were going to stay and not go any further and then when something finally burned through and broke apart, moving up a little further to settle a space closer to the middle of the X.

Just a word or two, she said to him, that’s all I want you to say.

He said something back to her, something deep in his throat, but her ears were listening to a dim buzz that had started up deep inside her head, and she couldn’t hear him.

What? she said. What? One foot and one hand had reached almost to the opposite corners of the bed and she strained, trying to make that line of the X straight and true before she turned her mind to the other line.

He moved above her, and suddenly the first line fell into place and locked itself, and the little burning spots along that whole leg of the X began to gather themselves and move more quickly from each end toward the middle where they might meet.

The buzz inside her head that wouldn’t let her hear suddenly stopped the way you would click off a radio, and the sound of a mockingbird’s call somewhere outside came twice and acted like something being poured into her head. It moved down inside like water and made two little points of pressure which were the bird calls and which stayed, waiting for something.

You talk to her, she said to him, her mouth so close to the side of his head when she spoke that her lips moved against the short hairs growing just behind his ear. I hear you say things to her. In the night. I hear you in the night. Lots of times.

Her other foot and hand were moving now on their own, and she no longer had to tell them what to do. The fingers of the hand reached, stretched, fell short, tried again and touched the edges of the mattress where the two sides came together. The green and gold spread moved in a fold beneath the hand, and as it did, the foot which formed the last point of the two legs of the X finally found its true position, and the intersecting lines fell into place at last, straight as though they had been drawn by a ruler. And whoever was looking at her from above could see it, the two legs of the X drawing to a point in the middle where they crossed and touched, and something let the burning points know the straight path was clear, and they came with a rush from each far point of the two lines, racing to meet in the middle where everything came together.

Say it, she managed to get the words out just before all of it reached the middle which was where she was, and he said something, but she couldn’t hear anything but the fixed cry of the mockingbird and she blended her voice with that, and all the burning points came together and touched and flared and stayed.