Читать книгу Grief’s Liturgy - Gerald J. Postema - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Day I

ОглавлениеDay I: Dawn [Lauds]

I have always known

That at last I would

Take this road, but yesterday

I did not know that it would be today.

—Ariwara no Narihira

Linda, because you departed so suddenly—at least it seemed sudden to me and to your friends who gathered around you that night—you have left to me the task of gathering and reassembling the fragments of our love. Not because our love was broken, although it needed some tender maintenance, and not because it had been neglected, although at times lately we tended to it only as background to other pressing tasks. Rather, the work of gathering must be done now because this love was so rich and generous, so joyous and fruitful, that it scattered seeds liberally and carelessly and now the flowers are growing everywhere. The gathering itself is one of those flowers—love binding up love, love binding together love in the hope of bringing forth love.

I am inadequate to the task, Darling, but I jealously keep it for myself. No one can, no one will, gather our love with as much right or as much care as I shall. Gathering and binding these scattered seeds of our love, not for display on a shelf as a work well done, but as a wondrous living thing that will continue to grow in startling new ways as the years unfold.

My dearworthy darling,

stay close.

I need your hands

to help me gather

and your breath

to inspire.

Day I: Daytime (1)

Even youths will faint and be weary,

and the young will fall exhausted;

but those who wait for the Lord shall renew their strength,

they shall mount up with wings like eagles,

they shall run and not be weary,

they shall walk and not faint.

—Isaiah 40: 30–31 (NRSV)

Linda and I read these words on the morning of that day in late January, 2006, when we met with her oncologist to begin her first clinical trial. It was a regime that brought her life back to nearly normal for several months. We were full of fearful apprehensiveness and uncertainty that Monday morning, but already, even then, Linda’s strength was evident. Her determination to face the reality of her new life directly and with courage could be seen in her eyes. It was a difficult task for her. Yet, for two years her courage, clear-eyed realism, and gentle grace never faltered.

I wish I had her by my side now, helping me through this new trial. I fear I have neither her strength nor her courage. Worse, I don’t have her calming words, her soft and caring touch, and her gentle eyes to sustain me. And sometimes . . . sometimes, the pain is more than I can bear.

Day I: Mid-Morning [Terce]

For love is as strong as death . . .

—Song of Songs 8:6 (NIV)

Linda died just two weeks before our thirty-ninth wedding anniversary. We were married on Memorial Day weekend, 1969. We were just kids, not yet 21 years old. Our story began nearly five years before that, in November of 1964, when Linda asked me out for our first date. Actually, if legend is to be believed, the first sparks of our love may have been struck long before that when we were kindergarten classmates. You see, Linda and I did not fall in love; it did not just happen. Love was prepared for us; it prepared us and nurtured us. In its embrace we matured into adults, and as we matured, the embrace grew stronger, the roots struck deeper. Our love was tested—by shattering disappointments, by long periods of physical separation, by thoughtless and long-regretted wounds—but it proved stronger for the testing, deeper for the challenge. Our rich, shared, and mutually treasured history and the love it nourished has extraordinary tensile strength. Stronger than death.

Day I: Noon [Sext]

Loud as a trumpet

in the vanguard of an army,

I will run ahead and proclaim.

—Rilke

Linda reacted to talk of her courage with a wry smile, not believing a word of it. Friends called it extraordinary courage, but she insisted it was nothing more than facing reality. “It’s not courage. When something like this happens, you just call it what it is, and deal with it.”

The truly courageous may not be the best detectors of courage.

Linda would not be comfortable with elegy. She hated embellishment. “Just tell the story, Jerry,” she would so often say. “Leave out all the extra stuff and get to the point.” She preferred the light of the sun to the glow of sentiment.

I, on the other hand . . .

I want to paint her in brilliant colors “in one broad sweep across heaven.”

Day I: Daytime (2)

Diary entry: Friday, July 11, 2008

I have been feeling especially vulnerable and at sea this week. For most of the day on Monday I experienced abdominal pain, and in the evening I discovered I was bleeding from my gut. Disoriented and alarmed, I drove myself to the emergency room. A series of tests administered through the night showed that nothing was seriously wrong. I was discharged Tuesday, armed with antibiotics to fight the invading infection. The bleeding had shocked me, but what knocked the pins from under me was the realization that for the first time since I was a teenager Linda was not by my side, calmly assessing the situation and focusing on what needed to be done. Like an earthquake victim, I felt that something absolutely solid, a point of reference for everything else in my experience, was no longer there.

Day I: Afternoon [None]

John of Damascus wondered whether any pleasure in life is unmixed with sorrow. Grief asks whether sorrow will ever again permit pleasure into the mix.

Diary entry: August 2, 2008—7:20 a.m.

I sit here in the airport waiting for the departure of my flight to Chicago. Today I begin a ten-day trip via air, train, and automobile to Chicago, Seattle, Vancouver, and back to Chicago. It is the first vacation trip I can remember without Linda. I feel apprehensive and not a little fearful. Can this trip hold any pleasure for me? How could there be pleasure if it cannot be shared with her? Can I bear for ten days the heavy burden of emptiness I carry? At home I could lean on friends if my emotional skies turned dark. And I had my work to distract me. Yet, I don’t want to be distracted. I’m living a paradox: I want to find a way of living without Linda that is not living without her. When at work, I live without her. That’s the last thing I want.

My hope is that this time away from work will give me an opportunity to think about what is ahead for me, about how to live into the future. I am entirely at sea about that future. With Linda gone I scarcely know who I am. I feel like an adolescent again, with one major difference. As an adolescent I didn’t know what to do with my life, with my future, but I never doubted that there was a future for me. The future was there, a vessel to be filled, though I knew not how. Second adolescence comes with no such assurance. I am not sure there is a future for me, or at least I am not sure whether there is one worth filling. Life without Linda is grim, colorless, and painful. Why live with this? Can I find something that moves me again? I do not know adult life without her. I have no adult memory that is not filled with her presence. Life, perhaps, can go on without her; but can my life go on?

[Sung]

Lord help us to gather our strength in difficult times

So that we could go on living

Believing in the meaning of future days.

—Zbigniew Preisner

Day I: Twilight [Vespers]

C. S. Lewis writes:

Bereavement is a universal and integral part of our experience of love. . . . It is not a truncation of the process but one of its phases; not the interruption of the dance, but the next figure. We are “taken out of ourselves” by the loved one while she is here. Then comes the tragic figure of the dance in which we must learn to be still taken out of ourselves though the bodily presence is withdrawn.

I cannot accept that our dance has not been truncated. It has. We were in mid-stride. We were just about getting it right. Sometimes we were really spectacular—dancing with the stars. Sometimes we were pedestrian—inconsistent, but showing promise. We just needed a little more practice.

Still, Lewis does hit the right note at the end of this passage when he writes, “to love the very Her, and not to fall back to loving our past, or our memory, or our sorrow, or our relief from sorrow, or our own love.” That’s the great difficulty, I believe, and my great fear. In this new phase of our dance of love, how am I to love Linda, the very her, and not my memory of her, or some fiction I have created of her? Loving the beloved who has died, Lewis observes, is like loving God:

The earthly beloved, even in this life, incessantly triumphs over your mere idea of her. And you want her to; you want her with all her resistances, all her faults, all her unexpectedness. That is, in her foursquare and independent reality. And this, not any image or memory, is what we are to love still, after she is dead.

But “this” is not now imaginable. In that respect H. and all the dead are like God. In that respect loving her has become, in its measure, like loving Him. In both cases I must stretch out the arms and hands of love—its eyes cannot here be used—to the reality, through—across—all the changeful phantasmagoria of my thoughts, passions, and imaginings. I mustn’t sit down content with the phantasmagoria itself and worship that for Him, or love that for her.

Lewis seems right about this. But he names a challenge that I don’t know how to meet.

One way I have tried to meet it is to gather, greedily, perceptions and stories of Linda from others who knew her, who saw sides of her I rarely saw. I grieve that I will never again be startled by her unpredictable, utterly singular self, surprising me again, giving birth to new dimensions of our love, revealing new facets of the diamond.

Day I: Close of the Day [Compline]

[Sung]

| In manus tuas, Domine, | Into your hands, O Lord |

| Commendo Spiritum meum: | I commend my spirit: |

| Redemisti me, Domine, | For thou hast redeemed me, O Lord, |

| Deus veritatis. | God of Truth. |

—Roman Breviary

Day I: Night [Vigil]

Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord.

Lord, hear my voice!

My soul waits for the Lord

more than those who watch for the morning,

more than those who watch for the morning.

—Psalm 130:1–2a, 6 (NRSV)

Time is the canvas

Stretched by my pain.

—Rilke

Grief’s Anguish: Night throws darkness over the grieving soul. Daylight sometimes makes it possible to see through the fog of sadness, but nighttime drives out that one grace. Nighttime is the hour of grief’s anguish. Nighttime can happen any hour of the day. Sometimes, as Rilke puts it, grief encases me like a massive rock:

I am so deep inside it

I can’t see the path or any distance:

everything is close

and everything closing in on me

has turned to stone.

It is like nothing else in my experience; I am unable to get my bearings, movement seems impossible.

Since I still don’t know enough about pain,

this terrible darkness makes me small.

In my grieving, I have allowed sadness in the door when it knocked. But grief’s anguish never stands politely at the door. It doesn’t knock, it doesn’t announce itself. It bursts in, bludgeons me, grabs me by my jaw and reaches down into my stomach and pulls my gut inside out. Grief’s anguish is raw, utterly physical. It rudely shoves thought entirely out of the room. It is mindless and mad. Uncontrollable. Demonic. I am in its power, powerless; suspended, lifted off the ground and out of time. I am unable to see beyond the moment, unable to see. The cries echoing from the walls around me startle me with their ugliness.

The pain continues to wave over me!

Stop it, O God,

please stop it!

. . .

I think I’m in control,

but I can’t stop

the undulating ache

that wells up suddenly

and overwhelms me

until I collapse

from grief.

—Ann Weems

Grief’s anguish can be conjured by a thought or memory, by the to-do list found in the bedside table, the unfinished knitting on the closet shelf.

Remembered happiness is agony;

so is remembered agony.

I live in a present compelled

By anniversaries and objects:

your pincushion; your white slipper;

. . .

the label basil in a familiar hand;

a stain on flowery sheets.

—Donald Hall

It takes nothing more than touching something of hers to blow the door wide open. One of the most powerful attacks of grief’s anguish came when I brushed against one of Linda’s favorite jackets hanging in the closet next to my sport coat.

Grief, at its deepest, is physical. Utterly, frighteningly physical.

“How much does matter matter?” the poet Mary Jo Bang asks. “Very.” is her simple answer.

What I want desperately is Linda’s touch. The pain of its absence is sharper than the thrust of any knife.

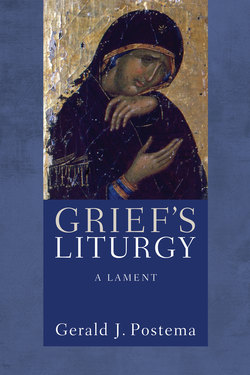

The pain is evident in the icon of the Lamenting Virgin.

Lamenting Virgin (Theotokos Threnousa)

The depth of the virgin’s grief is evident in her deep-set eyes; too deep, it seems, for tears. Yet it is not her countenance that expresses the deepest truth of grief; it is her gesture. The inclination of Mary’s head and the position of her hands recall other, much more familiar icons. In one, Theotokos Eelousa (Virgin of Compassion) or Theotokos Glykophilousa (Virgin of Tenderness)—like the Lady of Vladimir—Mary holds the infant Christ tenderly in her arms and inclines her head to receive a kiss from the infant, who reaches his hand to her neck. Another, a form of the pieta, the epitaphios threnos (lamentation upon the grave), depicts Mary cradling the head of the dead Christ who has just been removed from the cross. In the first, the joy and love of mother and son are palpable. Yet, in some versions, the virgin’s eyes are sad with the knowledge of the passion to come. In the second, Mary again holds the body of her beloved, now sacrificed and lifeless, but still in her arms. In the Lamenting Virigin, we encounter gesture again, the love and sad tenderness is there, but, in the place of the beloved Son there is emptiness. “Alone she saw to birth as now she has seen to the burial. She took and held the precious child and prepared the undefiled body for the grave.” But the arms are not just empty; the arms are perceptibly in motion, drawing the absent One closer to her breast.

I know no more powerful, no more achingly truthful depiction of the persisting experience of grief than this. All the gestures of love I had learned over the years are hollow after Linda’s death. Meant to surround her, to make my heart known to her, my arms now ache from the emptiness. The weight of such emptiness has no measure.

And yet, there is more to the message of this image. For it is the infant so tenderly held that gives the gesture its meaning. The virgin’s inclination, bearing, and being are shaped by the love in that gesture. Her love, even in her time of absence, is formed around her beloved, a love returned with equal tenderness and depth by the infant Christ. Likewise, although the absence of the infant, and of the dying Lord, can never be denied, the very shape of the virgin’s love makes the beloved almost visible.

Lady of Vladimir

Epitaphios Threnos