Читать книгу Treaty Shirts - Gerald Vizenor - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

ARCHIVE

The Great Peace of Montréal became the mainstay of our visionary and catchy petition that autumn for the right of continental liberty. Seven native exiles resumed that singular treaty of peace in tribute to thousands of our native ancestors, the ancient voyageurs and coureurs de bois of the fur trade, and citizens of New France.

That theatrical peace treaty was plainly signed forever and has continued in native stories as a trustworthy entente after more than three centuries of diplomacy, territorial wars, colonial turnabouts, separatism and reservations, and the many obscure resolutions of sovereign nations.

Seven native exiles teased the former colonial regimes to restore that great peace of the continent and recognize a singular seat of egalitarian governance at Fort Saint Charles on Manidooke Minis, the island of native liberty, mercy, and spiritual discretion near the international border of Lake of the Woods.

Archive is my nickname, one of the seven exiles.

The Constitution of the White Earth Nation, once our chronicle of continental liberty, was created with moral imagination and a distinct sense of cultural sovereignty, the perseverance of native delegates, and a certified referendum of citizens, but the duties of our democratic government were carried out for only twenty years.

The rightfully elected government, related community councils, and judiciary were abandoned overnight when the original treaties and territorial boundaries of the White Earth Reservation were abrogated by congressional plenary power on October 22, 2034.

The exiles were sworn delegates to the constitutional conventions, and then with the defeasance of treaties and governance the seven exiled natives turned to the irony and tease of native stories, and a chance that the great union of peace would overturn in spirit the course of termination and native banishment.

The Constitution of the White Earth Nation would continue as an autonomous native government in exile, we resolved that autumn, with the recommenced ethos of the Great Peace of Montréal at Fort Saint Charles.

Native traditions were turned into kitschy scenes at casinos, the conceit of culture, vain drumbeats, and with a bumper cache of synthetic narcotics, but native stories, the rough ironies of our liberty, and creative starts and elusive closures, outlasted the treachery, clandestine chemistry, the empire warrants, and the monopoly politics of entitlements.

Natives have forever escaped from the treachery of federal treaties, ran away to adventures, love, war, work, and money, broke away from reservation corruption, but we were the first political exiles with a constitution. Liberty has never been an easy beat, tease, or story.

The seven exiles and a native soprano in her nineties were steadfast that any history must be envisioned with native stories, and our ancestors were rightly saluted, an easy gesture to more than two thousand native envoys who gathered three centuries ago on the Saint Lawrence River near Montréal and entrusted forty orators and chiefs to sign by name and totemic mark the great peace union with the royal province of New France.

Justice Molly Crèche, one of the native exiles of liberty, naturally praised the sentiments and native signatories of that historic peace treaty, the first colonial empire to honor native sovereignty and continental liberty. She declared that native stories were survivance and diplomatic trickery, and our petitions to continue that peace treaty entailed ironic reversals of the colonial cession to Great Britain in the Treaty of Paris.

La Grande Paix de Montréal has never been abrogated in tact or forsaken in diplomacy. Yet, that historical union and memorable peace treaty was directly connected to the decimation of totemic animals in the empire fur trade and has never been forgiven in the court of shamans, or revised with irony in the native stories of colonial enterprise and the shakedown of liberty.

Come closer, listen to the steady crack of totemic bones, trace the bloody shadows and getaways, endure the steady wingbeats of scavengers, and count out loud the seasons and centuries of peltry stacked in canoes, the gory native trade and underfur treasure of two empires, and the everlasting agony of the beaver.

The beaver and native totems were sacrificed once in the empires of the fur trade and orders of courtly fashions, and then totemic animals were converted into tawdry casino tokens, the new crave of peltry and games of chance.

The animals of cagey casino cultures were considered more as a nuisance and the sources of new diseases than the traditional inspiration of survivance totems and continental liberty.

Native storiers and artists portrayed the outrage and cruelties of cultural memory, and recounted in words and paint the ruins of native totems and haute couture of the fur trade, the fancy curtains, carpets, and maladies of casinos. Native creation stories were derived from totemic visions, and the course of our survivance must relate to that natural motion of continental liberty.

Hole in the Storm painted a series of grotesque casino gamers aboard a giant luxury yacht on Lake of the Woods. The cheeky triptych, Casino Whalers on a Sea of Sovereignty, portrayed the great waves, backwash, and bloated gamers hunched over rows of watery slot machines with beaver and totemic animals in place of the cherries, numbers, and bars on the reels of regulated chance.

Hole in the Storm was one of the seven exiles, and the nephew of Dogroy Beaulieu, the renowned native artist who was exiled almost twenty years earlier for his shrouds of totemic creatures and scenes of decrepit casino gamers.

The White Foxy Casino commissioned seven original paintings by Auguste Gérard Beaulieu, or Hole in the Storm, a painterly native nickname, and at the same time casino curators organized an atonement exhibition to celebrate the distinctive and once traduced portrayals of his great-uncle Dogroy Beaulieu.

Douglas Roy Beaulieu, a visionary artist, created a sense of native presence and abstract portrayals of animals, birds, and totemic unions of creatures. His avian shrouds were acquired by museums around the world. Yet, the revered painter was menaced by the tradition fascists and banished from the reservation because of the portrayals he created of casino gamers connected to oxygen ports on slot machines, and because of his evocative images of totemic visions. The miraculous traces of natural motion, the spirits and shadows of dead animals and birds were revealed on linen burial shrouds.

The Midewin Messengers, a scary circle of blood count connivers, coerced several native legislators to disregard the specific article in the Constitution of the White Earth Nation that clearly prohibited banishment. The political ouster was reversed several years later, but the abuse and disrespect of a great native artist could not be undone with a customary tease, turnabout gossip, casino drumbeats, or generous waves of cedar smoke.

Dogroy actually thrived as an artist in exile, and, with the mongrel healer, Breathy Jones, earned a prominence he could not have achieved in the crude casino culture on the Pale of the White Earth Nation.

Dogroy connected with other painters and established the marvelous Gallery of Irony Dogs in the abandoned First Church of Christ, Scientist located near Elliot Park and the historic Band Box Diner, a distinctive native quarter in Minneapolis. Some fifteen years later a heroic bronze statue of the militant poseur Clyde Bellecourt was erected on the corner near the Gallery of Irony Dogs.

The best native trickster stories were teases of creation, traditions, marvelous contradictions, and ironic enticements of weird and visionary flight. The stories were never about the abstract patois of treaties, entente cordiale, or native sovereignty. Now our stories must tease and controvert the capitol promises and betrayals as much as the sex, creation, and hardy escapades of lusty tricksters. Some stories were risky, erotic hyperbole, and with no sense of shame because the sex conversions, masturbation, and other seductive adventures started with our ancestors. Candor was natural and the fakery of literary denouement was not necessary.

Newcomers, fur traders, missionaries, and the course accountants of reservation enlightenment seldom weathered the teases or survived the mighty twists of trickster mercy. Truly, the new sector governor deserved no greater standing in native stories than federal agents of the past century.

The United States Congress abrogated more than three hundred native treaties in a special session that Sunday, October 22, 2034, and at once substituted federal sectors for reservations and state counties to manage the burdens of social security and hundreds of other national strategies, entitlements, and endorsements.

The Congress considered but could not enact more reasonable measures to decrease the enormous national cost of covenants and entitlements, so the political outcome was only promissory, a compromise that ended native treaties, the entente cordiale of native sovereignty, and, at the same time, the legislators voted to commence with the national endorsement sectors.

Congressional plenary politics once more downplayed and then abrogated as a mere compromise native egalitarian governance, continental liberty, and cultural sovereignty. The national political cuts, causes, and economic enactments were never more than the revels of dominion and monopoly agencies, and the remnants of treaty reservations were at most the caretaker remains of deceptive sovereignty.

The poses of entente cordiale and native sovereignty were bureaucratic ruses, and yet some weary natives were encouraged, other natives, storiers, literary artists, and painters, resisted the political maneuvers, and many others capitulated, once, twice, more, and then came the inevitable reversal, the plenary abrogation of our continental entente, treaties, and native liberty.

Godtwit Moon was nominated the sector governor straightaway and the very next day he posted an order to banish seven natives from the reservation and sector. The order indicated only our nicknames, Archive, Moby Dick, Savage Love, Gichi Noodin, Hole in the Storm, Waasese, and Justice Molly Crèche.

The Constitution of the White Earth Nation, and other native nations, were denatured by the plenary abrogation of the entente and treaties. The territorial domain of native sovereignty had been erased, and the precise constitutional prohibition of banishment was not enforceable.

Seven natives resisted the demise of governance, but we were immediately renounced and rebuked as extremists and exiled. The constitution was our only native trace of sovereignty, at the time, so we resorted to a diplomatic strategy of continental native liberty provided by the great and everlasting peace treaty with New France.

Forty native nations were signatories to La Grande Paix de Montréal in 1701, and for about sixty years the treaty provided peace for natives, fur traders, and the citizens of New France. The exiles were eager to double back with stories of earlier treaties and continental liberty because our native constitutional governance had been denied by the plenary power of the United States Congress.

The Great Peace of Montréal recognized by name and formal negotiations, empire cues, signatures, and totemic marks the unmistakable sovereignty of native nations in New France, New England, and the Great Lakes.

Hole in the Storm seemed to envision scenes of native exile, but the situation of our banishment was not the same as Dogroy Beaulieu or the renunciation of the spectacular triptych. The Casino Whalers on a Sea of Sovereignty portrayed the mighty motion of waves, the sleaze of casino overseers, grotesque gamers over slot machines, and the catastrophe of native sovereignty.

The abrogation of the reservation treaty, rescission of the constitution and native governance, and our exile that autumn resulted in an escape cruise on the Baron of Patronia, that marvelous houseboat of survivance and native sovereignty. We became the new native expatriates of continental liberty on Lake of the Woods.

Justice Molly Crèche, Moby Dick, Savage Love, and the other exiles told memorable treaty tales, the tease and ironies of princely names, workaday mockery, and the giveaway contingencies of government. Federal treaties were always hazy but the stories of the exiles were buoyant, a mirage of birthrights, bogus advances of civilization, and the steady comic teases and parodies of federal agents for more than a century. The new treaty tales were easily derived from the new regime and obscure duties of the endorsement sectors.

Waasese was an innovative storier with lasers, those beams, shimmers, and emission of radiation but not words or paint. She created incredible holoscenes, the precise projection of light, the haunted scenes and figures over the reservations, lakes, and cities. Most of the laser images were familiar, George Washington, Geronimo, Mae West, John Wayne, Sitting Bull, Bob Dylan, and Neighbor Smithy who wore a Vine Deloria Peace Medal, for instance, were seen several times in natural motion with Diane Glancy, Sherman Alexie, Louise Erdrich, Joy Harjo, George Morrison, David Bradley, and many other native writers and painters over the White Foxy Casino.

Waasese earned her nickname, a flash of lightning, in a laser laboratory as a graduate student, and created a laser scene of presidents and prominent natives that reached over the Mississippi River near the University of Minnesota. The holoscenes were in motion, faded, and then vanished in the night sky.

Waasese was constantly teased, of course, and given several nicknames, Tree House, Laser Carpenter, Crazy Beam, Chicago, Timber Maven, and at last the native word Waasese. The Chicago nickname was a historical reference to the reservation white pine that had been cut to build the city. Some natives converted that nickname to zhingwaak, white pine, but Waasese, a wild flash of lightning, outlasted the other nicknames.

Chewy Browne, a native soprano in her nineties, a truly catchy treaty storier, was honored as a senior exile on the very night of our departure from a boat dock near the ruins of the Seven Clans Casino in Warroad, Minnesota. Chewy chanted the names of her nine fancy chickens that night, and then told stories about how the chickens had scurried and crapped on the roulette tables and outsmarted the security agents with elusive clucks, magical cackles, and crow boasts in the casino.

Native creation stories were visionary, never the same as treaty tales. The contrasts of creation, and the totemic union of animals were never counted down to the territorial metes and bounds of separatist reservations and the ruse of sovereignty. Fancy chickens, however, were both creation and treaty stories, and memorable scenes at the casino.

Chewy was a shaman with fancy chickens.

Justice Molly Crèche, a prudent storier of creatures and treaties, counted ancient natives by diseases, grieved over the agony of pared animals in the wild fur trade, and created a poignant metes and bounds of lethal outpost pathogens, that decimation of natives, and, at the same time, the ghastly estates of peltry.

“Natives once envisioned totemic associations, bears, wolves, sandhill cranes, but our ancestors were never the honorable escorts of animals in the fur trade. We are the storiers of conscience, cast aside, and yet natives must continue to nurture totemic associations, the auras, spirits, and shadows of animals,” declared Justice Molly Crèche.

Homer Drayn, vice chancellor of the William Warren Community College, announced in a formal statement, “Justice Crèche might have become a high court justice, but the hearsay of wild sex with animals and conversion of the tribal court to beaver rights and bear necrostories regrettably ended an eminent judicial career.”

Drayn was an edgy native lawyer and constant rival to serve on the constitutional court. He had actually initiated the vicious rumors that Justice Crèche was having sex with mongrels and wild animals.

“Justice Molly Crèche always honored the standing of beaver, bear, moles, gypsy moths, juncos, spiders, and little brown bats in court,” chanted Moby Dick.

“Crèche was right, she was always right about the rights of animals and their day in court,” said Gichi Noodin, the steady voice of Panic Radio. “The trouble was, most natives worried more about the casino than about totems, mongrels, or fur trade animals, and the honorable justice was burdened with more cases and testimony about casino sleeve dogs than abandoned and abused children.”

The White Earth Reservation was created by treaty on March 19, 1867. Minnesota had been a state for almost nine years when the federal government carved out a section of woodland and lakes for a reservation. That thorny episode of state separatism has never been a pleasurable source of native memories or stories, and for more than a century the treaty has never been a reliable warranty, never a true celebration of democracy, only a mockery of sovereignty and continental liberty.

Most natives remember the treaty tales and frightful situations when entire families were separated from their customary haunts, homes, and ventures, and relocated elsewhere on a federal reservation. The native resistance to separatism and treaty relocation was hardly recorded in national archives or state histories. The chronicles most celebrated were about the romance of the ancient fur trade, and favored timber barons who carried away the red and white pine on the White Earth Reservation.

Yet, in the face of constant government betrayals and crafty policies, natives endured and created an extraordinary democratic constitution, one of the prominent constitutions of the modern world, and resolved the devious mandates and feudal cache of saintly blood that was touted as the authentic trace and determination of native identities. Now, after two decades of autonomous governance our native state and constitution has been terminated, and the very protectors of the revered charter were exiled with a cast aside constitution.

The Constitution of the White Earth Nation, approved by a referendum of native citizens about twenty years ago, proclaims in the preamble that the Anishinaabe were the successors of a great tradition of continental liberty, a native constitution of families and totemic associations. These very principles and sentiments of native sovereignty and liberty would continue in a state of exile.

Justice Molly Crèche initiated at the same time as the egalitarian native government the White Earth Continental Congress, a native association that soon grew to more than three thousand members around the world. The Congress celebrated the creative achievements of natives since the establishment of the White Earth Reservation.

The Dominion of Canada was established four months later on July 1, 1867, and that day of independence has been celebrated every year. The coincidence of these three crucial events in continental culture and history, the Great Peace of Montréal, the congressional separation of natives and later abrogation of the reservation treaty, and the observance of dominion liberty, provided a chance to resolve the injustice of our exile, and secure the vision of the Constitution of the White Earth Nation.

The Canadian envoys of foreign and aboriginal affairs, national defense, and immigration were scheduled to arrive by boat to consider our formal petition to reconsider the original surveys and confusion over the international border, liberate the Northwest Angle as the Angle of Native Liberty, and secure Fort Saint Charles on Manidooke Minis, an island of spiritual power, as a native state, and to provide support and sanctuary for eight political exiles and the Constitution of the White Earth Nation.

The preliminary negotiations were scheduled on the deck of the Baron of Patronia, and later on Manidooke Minis. The Canadian envoys and agencies indicated they would consider the situation of eight exiles and native continental liberty. Summaries of the discussions would be broadcast nightly on Panic Radio.

The Canadian government acknowledged our fur trade ancestors and petition of ancient treaty rights to Fort Saint Charles, the first western post in the colonial province of New France. Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye, the military officer and trader, established and named the post in 1732 in honor of Charles de Beauharnois, Governor of New France. Canada mistakenly allowed the survey of the international boundary to include Northwest Angle, Fort Saint Charles, and other native land and islands in Minnesota.

The native exiles were remembered only by earned nicknames. Archive, the first narrator, poet, and novelist, Gichi Noodin, Great Wind, Captain of the Baron of Patronia and spirited broadcast voice of Panic Radio, Savage Love, an irony dog trainer and innovative unpublished writer, Moby Dick, exotic publisher and totemic guardian of deformed aquarium fish, Waasese, a laser holoscene scientist, Hole in the Storm, a visionary artist who earned an ironic nickname because he was a quiet painter at the very heart of a storm, Chewy Browne, the senior exile with a magnificent soprano voice, and Justice Molly Crèche, fur trade necrostorier and the steadfast advocate of totemic justice and animal rights in courts, declared a new native nation in exile at Fort Saint Charles in Lake of the Woods.

Chewy Beaulieu Browne was a delegate, twenty years ago, to the constitutional conventions, and she initiated the community councils and totemic associations that were essential to democratic governance. “If you ain’t tookin then I’m a lookin,” she loudly teased my great-uncle at the first convention, and he was taken, but they became very close friends and active in the community and totemic councils. Chewy enchanted the delegates then and the exiles now with her course of teases and emotive soprano voice. She sang the poetry of the preamble and the articles about irony and continental liberty.

Chewy was one of the thirteen Manidoo Singers. The singers honored the spirits of the dead with songs, including the despised governor of the sector, Godtwit Moon. She was determined at age ninety to live in exile, and would not be denied the right of exile on the Baron of Patronia.

Moby Dick started the ouster stories on the first voyage of exiles that autumn. The notice of our actual banishment was a handprinted poster mounted at the entrance to the casino. The poster noted that we were removed forever from the former reservation and new federal sector. The order was arbitrary, and everyone understood that we were ostracized only because we had resisted the congressional abrogation of the constitution and egalitarian governance, declared our confidence and absolute allegiance to the native constitution, and because of our wholehearted loyalty to new totemic associations, but not the national sectors.

Many natives returned to live on the reservation the same year the constitution was certified by almost eighty percent of the registered citizens who voted in a referendum. There was great excitement at the time, election debates were serious and constructive, several native judges of the constitutional court were confirmed, totemic associations and councils were underway, and the new library collection had more than doubled with the novels, poetry, history, art, and critical studies published by native authors.

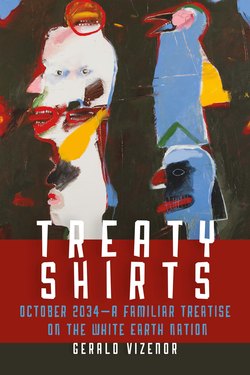

The eager delegates to the constitutional conventions initiated the new custom of Treaty Shirts on the same day that native citizens endorsed the Constitution of the White Earth Nation. The eight exiles carried on that shirty tribute to native governance for twenty years and wore the same unwashed shirt at conferences and legislative sessions, a ceremonial vestment of continental liberty. The odors of the shirts were nasty, and the conventions and native seminar stains were ironic archives, the traces and citations of hors d’oeuvres, silhouettes of chicken wings, spicy meatballs at banquets, and buffet spatters.

Tedwin Makwa, or The Bear, a native philosopher, was our garment mentor, and he was renowned for the stench of his embroidered cowboy shirt. He wore the same unwashed shirt at conferences, social and political events, and in the classroom for decades. Traces of his travels and activities, overnight binges, messy sex, pizza and burger prints, stains of mustard, wine, mayonnaise, and fry bread ooze were the distinctive codes of cryptic stories and native reciprocity.

Makwa was truly a master of ironic stories, but only strangers, the uninitiated, or those with olfactory disorder would sit next to him at a conference or a restaurant. The stench of his cowboy shirt with more than a decade of sweat, grease, and wine would foul the air and overpower any ordinary conversation. Friends held their breath when he reached out for a hearty embrace.

The Constitution of the White Earth Nation was set more than sixty years too late in any critical calendar of continental liberty. Earlier the constitutional government could have become much stronger with the actual steady growth and prosperity of the nation rather than with the slow decline of the world economy and financial systems. The economic decline resulted in the abrogation of the reservation treaty and the ruination of the Constitution of the White Earth Nation.

There were many earlier native initiatives to create a democratic constitution, the very visions and strategies that would have connected with the first wave of native college graduates in the nineteen sixties, but the steady political putter and shame of federal agents, and the obvious trickery, lethargy, and corruption of older reservation leaders were too much to counter at the time.

Twenty years ago hundreds of natives returned with their relatives to the reservation, to a new constitutional democracy, with praise and anticipation of an ethical and worthy government. We were right about the merit, ethos, and virtues of autonomous governance, but never gave much thought to the reports on the incredible race of credit and the national debt. We had overlooked the enormous increase in trust endorsements, once-named entitlements, and regulations, and the worldwide government debt and economic decline. The conditions became so serious in the past decade that some news and editorial reports declared the crises an era of political retractions, banishment and renouncement, a “national dust bowl of endorsements,” public obligations and debts, debts, debts.

Children, elders, horses, pets, boats, summer cabins, snowmobiles, stores, movie theaters, markets, malls, and houses were abandoned in the millions around the country, and we were banished along with an autonomous native government when treaty land and reservations were converted overnight to federal endorsement sectors by congressional plenary power.

Clément Beaulieu, my great-uncle, pointed out this giant double catch of plenary power when the constitution was ratified, a tricky catch we did not fully grasp at the time, that congressional actions could terminate the reservation and leave the constitution without a native venue, domain, or territory to practice governance.

Plenary power was absolute, but not comparable to the elusive traces and turns of demons in native trickster stories. The conversion of reservations and state counties to federal sectors was actually ironic because we had been weakened by our own vitality, gentle conceit, and hearty determination to create a constitutional government. We were convinced at the time that the honor of a democratic constitution would never be denied in the modern world.

Savage Love avowed that the word “abandonment is an absence, a passive accusation, inactive, and the words oust, banish, evict, exile, and chase were active, but neither the post nor promises were more than a tentative intention, and with no actual sense or significance, none.” She was always casual, and seemed to understate the philosophy of existential absence over presence, and yet repeated the point that the ratified articles in the constitution were mere intentions, autonomous in practice, and we were the natives who created the actual substance with each word, and the most recent recitation was in the sentiments of exile.

“The constitution is more active in exile than it was bound to the territory of a federal treaty,” Gichi Noodin shouted, “so, our exile made perfect sense, a constitution of new continental liberty.”

“No, no, abandoned children and mongrels are actual, real, a heartbeat, a presence, not the same as moored boats and empty houses,” moaned Moby Dick.

“The words have no meaning or native story,” declared Savage Love. “The notions of abandon and renounce were never states of gravity because words were always stranded in emotion and nostalgia, and the tease of the next listener or reader, the word was never an actual person, mongrel, or totem, the words are naught but a crease of sound.”

“Right, the meaning of the words in the constitution change with the users, and in the same way that stories on Panic Radio were never, never the same,” said Gichi Noodin. “Why would natives listen day after day if the stories were always the same?”

“Children and animals, abandoned or not, have real names and legal standing in the world court of justice, but repossessed cars and foreclosed houses do not,” said Justice Molly Crèche.

“Cars and abandoned machines were never sincere,” said Hole in the Storm, “but the great spirit of animals have standing in art and any serious native court of stories.”

“The bat and animal totems double the standing of humans,” said Waasese. “The totems were envisioned and animals and bats have always been the reserved traces in our stories and the precedent of courts.”

“Names, machines, death, empty, no meaning, nothing, death nothing, names nothing, words are not an absence and not a salvation or memory, words are created and last only in the moment of a tease or shout,” said Savage Love.

Maybe, but the stories of the exiles in Treaty Shirts were eternal, and in the same way the articles in our constitution have always had meaning. The words were in the clouds that love to hear a native dream song. We were banished, seven constitutioneers with exile nicknames, outside of the federal sectors, and yet the ironic stories of our names, and posted notices of our exile, have meaning and significance.

“Nothing more than native nostalgia, no significance,” declared Savage Love. She smiled, and raised one hand in silence, a gesture of patience and respect as one of the seven exiles, and then turned and walked away with five great exiled irony mongrels, Wild Rice, Sardine, Mother Teresa, Mutiny, and White Favor.

Savage Love earned her nickname as a tribute to the crusty mother of the poet and novelist Samuel Beckett of Dublin and Paris. Savage Love was an innovative novelist, and actually better suited to exile than a commune. She was the direct descendant of Chance, the sensitive and honorable native healer who taught dozens of mongrels how to detect the absence of irony. That has been an eminent practice, and more significant than any prayers for deliverance or the promissory politics of the federal government.

Chance and Savage Love were born on treaty land, but were never connected to a community. They lived with the artist Dogroy Beaulieu and several mongrel healers on the Pale of the White Earth Reservation and were ridiculed in stories. Chance, Savage Love, and the mongrels moved with Dogroy to the Gallery of Irony Dogs in Minneapolis.

Chewy and the seven exiles were banished along with sex criminals, dogs, and domestic pets. The federal sector banned the mere possession of dog food, and imposed work fines for those who were caught feeding birds, cats, or dogs. Mongrels, the great healers of natives, were abandoned in the hundreds on the sector, and were driven to search the overnight casino trash for food with the rowdy crows. The mature mongrels truly protected the weaker and dependent designer breeds on the sector. Three abandoned and dirty white Bichon Frisé, and several other catchy named terriers, learned how to carry on with the pure mongrels, and with the tricky manners of sector survivors.

The abandoned mongrels ran in packs and rehearsed their lonely nightly howls near the treelines. The timber wolves disregarded the mongrel howls. The wild distance of so many domestic generations could not be overcome even with a practiced bay. The renounced miniature sleeve dogs were thwarted with the genes of insider pedigrees, but they ran happily with the pure mongrels, forever burdened with a shallow, anxious, and inane yelp, yelp, yelp.

“Mongrels never abandon their young, or any young dogs, pedigree or not, deformed or not,” said Moby Dick.

Mongrels have never forgotten their origins and easily grasped the meaning of irony and abandonment on the sector. The mongrels were healers, and have endured the curses, sorrow, and endearment of humans for thousands of years.

Savage Love worried that the five mongrels at her side would only appreciate the words abandonment and rescue in ironic stories, and bark at the absence of irony. Mongrels at casino dumpsters, and the creepy poses and declarations of sector toadies and politicians, were obtuse and truly ironic and the absence deserved a bark, but mongrel barks were banned and dangerous.

Savage Love declared that “only a cruel and benighted separatist would abandon our healers and great pointers of the absence of irony, or name a mongrel Cracker, Custer, Cur, Crud, Abandon, or Renounce, without a native tease and astute sense of irony.”

The mission priests created mundane and descriptive nicknames of mongrels in the early years of the reservation, White Paws, Big Spot, Bud, Joe, Kim, Gordy, Catch, Pickle, Manypenny, and Bear Heart. The mission sisters shunned the mongrels and wild animals, but demonstrated their love of native children and tolerated the redeemed mongrels, the shy mongrels that never nosed a holy crotch. Luckily the ecclesiastic nicknames of mongrels on the reservation were never Vice, Shame, Salvation, or Black Devil.

I was a novelist in the generous literary shadow of my great-uncle who wrote the constitution, and more than thirty books about natives. Most of the natives who returned to the reservation that first year of the constitution were trained and experienced teachers, lawyers, athletes, medical doctors, corporate accountants, an electronic engineer, a pirate radio broadcaster, an artist, fireman, musician, and a holographic artist and scientist. Rightly, we were always teased as constitutional newcomers and earned our nicknames based on manner, habits, diversions, and we sometimes earned more than one. The newcomers were commonly known on the reservation by their nicknames.

Surely our loyalties and constitutional allegiance were not cultural crimes that deserved banishment or termination. The principles of governance were abused and discredited by sleazy sector autocrats, and yet we could not deny that arbitrary decisions and policies were common for more than a century and sometimes celebrated in the modern ruins of continental liberty.

The visionary stories, treaty deceptions, and cultural ruins were never the same from one generation to the next, and the cultural conversion of casinos was only a proem to the extreme political narratives of national endorsements and the strange revisions of penalties and justice.

La Maison de Torture Extraordinaire, for instance, a reversal in the national practice of torture, would surely be more bearable than archaic political evictions, religious torture, and secret rendition strategies. The outcome would be the same but the new torture of solicitude caused no nightmares, psychic scars, or political crises. Separation with compassion, or banishment with no body trauma, was nothing less than removal and exile. There was no virtue in the cruel irony that our native ancestors endured arbitrary and malicious separation carried out by federal agents in the early years of the White Earth Reservation.

The exiles were descendants of the fur trade, and our ancestors once declared their loyalty to the French in the empire wars. Today, with loathsome stories and dreadful memories of the fur trade, we bear the surnames, totemic nicknames, and cultural distinctions of native exiles, and to create a new union with the spirits of animals we initiated totemic associations and constitutional councils to advise the new government. The original totems were created in the spirit of the animals, in ancestral stories of natural reason, the turns of seasons, eternal migrations of birds, and the common array and motion of wolf spiders, cicadas, bobcats, bats, kingfishers, carpenter ants, cedar waxwings, moccasin flowers, praying mantis, and coywolves.

Clément Beaulieu was a delegate and the principal writer of the Constitution of the White Earth Nation. Article Five provided that “freedom of thought and conscience, academic and artistic irony, and literary expression shall not be denied, violated or controverted by the government.”

The Anishinaabe told great trickster stories of creation and enticement, teases and quirky mercy, and scenes of visionary motion. These memorable stories were never translated rightly in the book, but natives have the moral imagination, the lure of totemic associations, the natural justice of stories and literary irony forever in the Constitution of the White Earth Nation, and in the ancient legacy of the Great Peace of Montréal.

Only a native constitution would include a clear and direct reference to artistic irony. My great-uncle wrote that the constitution must encourage ironic stories and art, create new totems, more than the mere imitation of the traditional birds and animals, and he specified that the totemic and community councils should “strengthen the philosophy of mino-bimaadiziwin, to live a good life, and in good health, through the creation and formation of associations, events and activities that demonstrate, teach and encourage respect, love, bravery, humility, wisdom, honesty and truth for citizens.” That good life, however, would never absolve the cruelty and spiritual abuse of animals in the fur trade. The cultural memory of dead totemic animals was unforgiven, never a constitutional clemency.

The new totems and cultural burdens of natives were hardly significant when compared with the decimation of animals, and demise of the original totemic associations in the furious continental fur trade of the past three centuries. No national separation strategy, treaty deceit, constitution, dominion, tiresome overcompensations of monotheism, or the romantic tread of enlightenment could absolve the outright cruelty and slaughter of animals for felt hats and furry fashions in Europe.

Our new totems and the constitutional associations that were founded in the name of wolf spiders, coywolves, bats, bobcats, deformed fish, and moccasin flowers, would never reconcile the native cruelty to the great spirits of the animals, and the mass murder of beaver, bear, marten, ermine, and deer in centuries of the fur trade. Some city squirrels, raccoons, caged birds, and most mongrels continue to trust humans, even after dogs were banished from the federal sector, but the spirits of the beaver and other animals remain forever distant and deny humans the right to hear their remarkable stories of survivance. Truly the spirits of the animals await the tragic outcome of human civilization.

Justice Molly Crèche protected the rights of animals in the courtroom, and she was the only jurist who honored the memory of the animals murdered in the fur trade. She argued that because so many animals were brought close to extinction, “necrostories, the testimony of native totemic associations, and hearsay of animal genocide were accepted as evidence in the courtroom.” Crèche continued to hear testimony in exile, and the court stories of exile were broadcast on Panic Radio.

Our totemic associations and heartfelt observance of natural motion were clearly a philosophy of bimaadiziwin, but the beaver would never again enable humans to stand in their daily presence and survivance culture or participate in their trust and natural duty.

The pushy game hunters resented the new totems of spiders, birds, bats, insects, and wild flowers, and at the same time they protected timber wolves. The poseurs were furious that the word wolf was specifically used in the constitutional totemic association of the coywolves and wolf spiders. The outward manly totems correlated directly with metal clamp traps, heavy weapons, bright lights, snow machines, and giant pickup trucks.

Mostly the catcalls, curses, and politics of resentment were concentrated on the actual constitution, the very ethical provisions of governance that denied the easy dominance of the tradition fascists and Midewin Messengers. The fascists favored a circular patriarchy, a fishy patchwork tradition of absolute authority, and conspired against the constitutional elections. They continued to undermine every practice of egalitarian governance. The fascists harkened to invented traditions, and perverted the sacred midewiwin, an obscure medicine dance, and an association of healers and great visionaries. So, the heavy hunters and traditioneers were eager to join the faction of authoritarian managers in the new federal sector. The blood count connivers emerged to reign over native identities a second time in reservation history.

No, we were not romantic utopians, crazed, or wanton state criminals. The national reports that we had committed a murder, violated the federal charter of sector migration, or simply traveled without permission, and disabled the drone monitors were not true. Our inherent and constitutional liberties were denied, and we were brazenly threatened by the new governor to vacate the old reservation and the new federal endorsement sector.

The Constitution of the White Earth Nation clearly prohibited banishment, yet we were ousted and our rights violated by a corrupt autocrat and private security agents twenty years after the constitution was set in motion with native citizens.

Precisely, we were removed, as our ancestors had once been ordered by federal agents to leave the treaty boundary of the reservation more than a century earlier for publishing the Progress, the first independent native newspaper critical of federal policies.

Paradoxically we were banished at the very same time that native children were taught the ethics and principles of the democratic constitution in nearby public schools, and many citizens carried a miniature copy of the egalitarian document as a native prompt of liberty. The dubious ethics of federal policies had actually advanced to a new level of hypocrisy. Native sovereignty and the doctrine of reserved rights were never mentioned or considered in the political conversion of treaty reservations and counties into federal trust endorsements sectors.

Waasese created marvelous laser holoscenes, lively and magical light shows, and the radiant scenes easily diverted the drones and distracted the sector security agents. The Specter Drones, aerial monitors, and miniature digital cameras were everywhere, mounted in trees and beams, at the casino, underwater, and in books, tablets and toilets, and managed by private surveillance agencies to detect and track human motion in the sector, but the silent drones could not always detect an actual native from a laser scene.

Yes, we rightly teased, tormented, and menaced but never murdered the first governor of the White Earth Sector of the National Sectors and Trust Endorsements. Godtwit Moon had already earned three descriptive nicknames, Mosey, for his casual manner when he was paroled to the casino, Husky for the color of his eyes that changed from luminous blue to amber, and Miskojaane for his bulbous red nose. He was a poseur, boozer, and vicious conniver who concocted native traditions in a federal prison, and was secretly paroled to the reservation through a new and ironic rendition strategy of generous treatment.

Godtwit Moon was released from federal prison in the last three months of his criminal sentence for larceny, extortion, possession of narcotics, and weapons violations, and moved to the new Saint Cloud La Maison de Torture Extraordinaire. The new regime of empathy and solicitude was a complete reversal of earlier torture and security rendition programs.

The French academies had prescribed more humane remedies, care and compassion, and Rendition de Gentillesse to counter the previous abuses and extreme renditions of narcotic, electric, digital, radiance, audio trauma, and the notorious torture of waterboarding.

Godtwit Moon and other poseurs extraordinaire learned how to practice a perverted and concise version of the native midewiwin, a sacred, obscure, and traditional dance. The new rendition prisoners were otherwise placated, exploited and completely overcome with daily doses of sincerity, shrewdly soothed and stupefied with praise, sympathy, tolerance, and manly candor, the four cardinal principles of the new state strategy of moderate corrections and Rendition de Gentillesse.

Gentle, meditative music was transmitted throughout the day and night in the rendition prison. Enya was the most common music of the night, the merciful music of solemnity. “Thank Heaven for Little Girls,” by Maurice Chevalier, “You’re Nobody till Somebody Loves You,” by Dean Martin, crooner of the casino Rat Pack, the resonance of violins by Mantovani, and Yanni compositions were selected for new affect encounter sessions on ordinary care, the tender touch and gaze, tease of truth and trust, notable pleasure words, cautious generosity, and other soothing music and meditative cues and voices were broadcast in distinct sessions on leadership styles and legal sexuality.

The alterable prisoners who completed the program were frequently hired by social services agencies to soothe the many worries of the elderly in sector hospitals and nursing homes, an ironic and creepy continuance of the extraordinary rendition instituted in France.

Godtwit Moon completed the rendition program, an anxious but clever softhearted poseur, and he was released early to the custody of the corporate manager of the White Foxy Casino on the White Earth Nation.

Godtwit chased the casino money, an easy maneuver, and was promoted for his gentle poses of native culture and compassion as a supervisor of the bars, restaurants, and slot machines. Strategically he devised a way to decrease the payout to gamblers, aerate the daily entrée at the three restaurants, water the drinks, and was promoted regularly by the casino management company. Some four years later he was nominated, for no other reason than his native poses and simulated casino compassion, to serve as the first governor of the new federal endorsement sector.

The native outrage over the conversion of the treaty reservation to an entitlement sector was only equal to the contempt for the arbitrary promotion of the new rendition parolee Godtwit Moon. The poseur never hesitated to simulate his praise of the heartfelt constitution and at the same time revel in the very ruins of an established and representative native government.

Godtwit arbitrarily retired seven dedicated casino employees, and the very next day he hired five parolees from Saint Cloud La Maison de Torture Extraordinaire as personal security sentries. The second night of his new reign he changed the official name of the White Foxy Casino to the Coy Care Casino, a new services institution of the National Sectors and Trust Endorsements.

Casino sovereignty was recognized more than sixty years ago, and most reservation casinos near urban areas became wealthy. The money, hundreds of millions of dollars, was actually a crafty switch or transfer of wealth from the losers to natives and casino managers, an ironic hand over of a mea culpa culture, considered regret money at the time. That huge transfer of wealth from ordinary citizens, mostly the elderly, and chronic gamers, was terminated overnight with the congressional abrogation of the treaties. The White Foxy Casino was a minor contender in the huge transfer of wealth to native casinos.

The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act meant to protect and monitor native casinos, but the basic notion was curious, even mistaken, that gambling was a traditional practice of native cultures. Rightly, games of chance were common, and enhanced with music, cultural teases, and ceremonies, but that communal pleasure does not directly relate to slot machines, and the avarice of casinos.

The White Foxy Casino was terminated by plenary power along with the treaty reservation and constitution, and the contingent legislation provided a rescue conversion of casinos to corporate contract ventures that would serve native and other citizens in sectors of endorsements. The original management company of the casino continued as the federal contract agency to carry out the new sector endorsement programs.

Straightaway natives nicknamed the security sentries the Peace Hookers. Godtwit and the Peace Hookers became the subject of the most exotic trickster stories, a natural respite from the ironies of rendition and sector politics. The elders were eager to share wider and more mature stories about the early nicknames of nasty federal agents. The niinag mangindibe, or dick head, the big head penis stories, were the most popular that first autumn of sector dominance. The Peace Hookers were monster dick heads in the new trickster stories.

Godtwit Moon was obviously despised, and feared, mocked, shunned, and sidestepped, but seldom teased because the native tease was truly a communal gesture of tentative and uncertain compassion. The tradition fascists and native toadies praised the heavy management style of the sector governor, the whims of gentle rage, and every sensible native citizen was evasive and renounced the very presence of the new sector poseurs.

The National Sectors and Trust Endorsements at White Earth converted the White Foxy Casino Hotel to the Coy Care Resident Hotel for native elders and disabled citizens, and the convention conference rooms became a medical services center. Many elder residents were relocated from nearby cities to the Coy Care Casino.

The social security and federal disability payments to some elders, the gamers and residents, were deposited directly to an account in the Coy Care Casino Bank. Godtwit was president, of course, of the new sector bank. Many native elders were very pleased to live in the hotel residence, eat at the three casino restaurants, and easily walk or motor in a chair to the slot machines. The standard gaming rules were revised to eliminate actual money and citizens were issued electronic tags with casino credit.

The native players received monthly credit points that could be won or lost at the slot machines, poker, blackjack, and other games. Clearly almost every player was expected to lose, but the automatic credits regulated the debt of elder players, and those who lost their monthly credits were obligated to work at the casino or resident hotel, and others on road crews or at sector institutions to restore the credits. Every sector native was required to work for endorsements and to restore with hourly labor the total monthly debts on Coy Casino Credit Tags.

Most natives who feared Godtwit and the Peace Hookers were cautious and only conspired to partake in cynical gossip, as cautious as they were about the taunt and curse of shamans, and reckoned at times with the whisperers and scandalmongers. That combination of nasty gossip and shamanic torments had chased away many federal agents and pompous poseurs in the past, but the new sector governor and management, shadows of the national debt, and severe economic decline would never be absolved with testy rumors. The sector haters and native exiles, however, were resolute about the removal of the rendition governor.

The Shaman Crease, a notorious and covert circle of native healers and tent shakers created and vigilantly distributed the magical Waaban Blue Union, untraceable narcotic concoctions, and at the same time practiced natural and traditional herbal remedies. The healers invited the exiles, several other dancers, and the showy sector governor to an ecstatic overnight dance and spectacular light show at the Boy Scout Camp at Many Point Lake.

The seven exiles wore Treaty Shirts that mysterious and unpredictable night, the same stained shirts that we wore at the ratification of the constitution, the sector revision of the reservation, and notice of our banishment. Treaty Shirts embodied our spirit, sweat, and loyalty to the constitution, and we wore the shirts unwashed at every convention and convocation in the past twenty years.

Godtwit Moon was distracted by our presence at the dance, of course, and tried to disguise his worries that we were there to curse him in our Treaty Shirts, but suddenly he smiled, turned his head to the side, and waved his hands to show compassion, surely a cynical gesture of Rendition de Gentillesse, the new politics of compassion.

Savage Love tied blue treaty bandanas around the necks of the mongrels of irony, and yet we worried that the governor might execute another ban of mongrels at the dance. The five mongrels smiled at the sector governor, a much wiser ironic and totemic version of rendition. The mongrels were designated healers in blue bandanas.

White Favor was a whistler, not a moaner, a whistler with a clear pitch, and that night he whistled several times at Godtwit and the two Peace Hookers who were invited to the dance at Many Point Lake.

The Debwe Heart Dance, an ecstatic native cavort of truth, was slightly revised that night to deceive the hefty autocrat who could hardly walk through the casino twice without turning slightly blue with worry and heart fatigue. The drumbeats and heart bounces were slowed, and a new cast of songs and stories were simulated and shortened in his honor, only the most common names of nature, white pine, cedar, sumac, waxwing, beaver, porcupine, and water moccasins. The governor was cornered in a circle of tricky shamans who chanted these common names with a clever curse and poetic simplicity.

Savage Love taunted the governor with stories about the extraordinary rendition of words, the gentle words of death, and the ecstasy of nothing, absolutely nothing, not a single thing, and she encouraged him to inhale a hefty mound of blue luminous powder served on a short cedar stave. Godtwit sniffed and reached for Savage Love, but she ducked and moved between the trees.

The Specter Drones circled the red pine and were seduced by the holoscenes of historical figures over the lake. Waasese projected three images of Distinguished Eagle Scouts, Gerald Ford, president, Neil Armstrong, astronaut, and Steven Spielberg, movie director, in honor of the Many Point Boy Scout Camp, and Christopher Columbus, Samuel de Champlain, Cotton Mather, Andrew Jackson, Chief Joseph, Geronimo, Babe Ruth, Hillary Clinton, Vladimir Putin, and the waxy laser crucifixion of Jesus Christ slowly vanished in a wave on the lake.

The Peace Hookers and other sector security agents were amused but not distracted by the laser shows. The agents, however, were scared away from the truth dance by nasty packs of feral mongrels.

Godtwit Moon inhaled the narcotic and promptly lost his practiced rendition poses. He became belligerent, smoky faced, and shouted two mundane heart dance versions of truth, “slot machines and fast sex,” and “hate cats, hate dirty pets,” and then he danced in the red pines near the shoreline of Many Point Lake. The poseur circled in the dark, sniffed the last trace of blue shine on his finger, and hallucinated the presence of native women, naked natives in magical flight. Wild Rice howled at the poseur and nosed his swollen gray ankles. His heart was weakened by subdued rage, and his crotch was stained with urine.

White Favor whistled a lively tune, and with other moans and bays the mongrels created a magical chorus in the red pine that night. Mutiny turned and brushed her lacy ginger tail on the thick thighs of the governor.

Packs of feral mongrels circled the heart dancers and growled at the treeline, an escape distance. The bright eyes of the mongrels flashed in the red pine, ten, twenty or more mongrels in natural motion. Sardine gestured with her wet nose, and we were convinced the pack was rightly tracking their prey, the paunchy governor of the sector.

Waasese created later that night holoscenes of erotic monks with various animals above the birch and red pine near the lake, scenes from stories in the Manabosho Curiosa, an ancient and obscure manuscript published by Moby Dick. The wide circulation of the erotic monk stories, and the indisputable allegiance to the constitution were the obvious cause of his banishment. The tradition fascists were clearly aroused and outraged, of course, at the sex scenes with timber wolves and bears, and because the publisher was a constitutional loyalist, had collected and nurtured deformed aquarium fish, and earned the nickname of a great white whale. White, the ordinary name of a pigment surely made the poseurs more anxious than the giant whale of fiction by Herman Melville.

Moby Dick had nurtured deformed fish in two huge aquariums at the White Foxy Casino, conspicuously located near the center of the slot machines. The deformed fish were given names of famous explorers. Christopher Columbus shimmered with four fancy pelvic fins, and Matteo Ricci swerved to the side with huge floppy pectoral fins. Jeanne Baret, the explorer and naturalist, was a bright, sociable goldfish with five dorsal fins. The new gamers paused at the machines and watched the magical motion of contorted fish in the enormous curved tanks. The fish were exceptional, double heads and dorsal fins, triple eyes, bent spines, marbled, spotted, and hideous overbites. The tank was backlighted and hues of blue shivered through the water. The curious fish nosed the thick glass, deformed even more by the magnification, and stared at the faces of the casino losers.

Moby Dick maintained the deformed fish were the modern art of nature, the fancy of abstract expressionism, a tease and creative crease of ancestry, although the artistic expression of four eyes, or three dorsal fins in natural motion were no more grotesque that the disabled gamers with oxygen tanks on the outside of the aquariums.

Waasese projected a blue laser bear and several monks masturbating, and other monks shimmered in a natural sense of motion and embraced cottontail rabbits. A monk with wild hair touched the moist underbelly of a gentle beaver. The holoscenes overhead, visions and mirages, and the devious dance of truth on the shoreline, were followed later with an incredible incident of vengeance and death.

Godtwit Moon turned his head from side to side, and traced with his finger the scenes of erotic motion that clear autumn night at Many Point Lake. Later the poseur was slowly squished to death under the light cleated tracks of a snow machine. No one would reveal who drove the machine back and forth several times over the bloody body of the sector governor. The face was crushed, and the heavy arms of the poseur twitched in one direction of the track, and the chest wheezed in the other direction.

The elusive pack of feral mongrels moved closer to the snow machine and one by one, patched mongrels and three pedigree miniatures, nosed the mashed remains of the sector governor. Some of the mongrels moaned, others sneezed, and rolled over in the moist weeds. The Bichon Frisé and a hairy Chihuahua whined over the body, and then ran away in silence.

Many natives had imagined nasty ways to murder the sector governor, but crushed by a snow machine was never mentioned as a strategy. One storier staked the poseur overnight for the wolves, but only vultures might consider his mushy, sour flesh. Moby Dick told one of the best stories, the slow submersion of the sector governor into the casino aquarium with deformed fish. Savage Love thought his body parts should be returned in small plastic sandwich bags to La Maison de Torture Extraordinaire. Gichi Noodin moved for an ironic banquet of cured sector governor on a sacrificial stake.