Читать книгу The Gospel in Gerard Manley Hopkins - Gerard Manley Hopkins - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

GERARD MANLEY HOPKINS is a singular figure in English-language literature. No other poet has achieved such major impact with so small a body of writing. His mature work consists of only forty-nine poems – none of which he saw published in his lifetime. Even when one adds the two dozen early poems written at Oxford and various fragments found in notebooks after his death, his literary oeuvre is meager in size, even for a writer who died in his forties.

Yet Hopkins occupies a disproportionally large and influential place in literary history. Invisible in his own lifetime, he now stands as a major poetic innovator who, like Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, prefigured the Modernist revolution. A Victorian by chronology, Hopkins belongs by sensibility to the twentieth century – an impression strengthened by the odd fact that his poetry was not published until 1918, twenty-nine years after his death. This posthumous legacy changed the course of modern poetry by influencing some of the leading poets, including W. H. Auden, Dylan Thomas, Robert Lowell, John Berryman, Geoffrey Hill, and Seamus Heaney.

As W. H. Gardner and N. H. MacKenzie observed in the fourth edition of The Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins (1970), “The steady growth and consolidation of the fame of Gerard Manley Hopkins has now reached a point from which, it would seem, there can be no permanent regression.” There is a mixture of relief and wonder in their statement. No one would have predicted the poet’s exalted position when the first edition was published, not even its editor, Robert Bridges, who spent much of his introduction apologizing for the poet’s eccentricities and obscurities. Hopkins currently ranks as one of the most frequently reprinted poets in English. According to William Harmon’s statistical survey of existing anthologies and textbooks, The Top 500 Poems (1992), Hopkins stood in seventh place among English-language poets – surpassed only by Shakespeare, Donne, Blake, Dickinson, Yeats, and Wordsworth (all prolific and longer-lived writers). His poetry is universally taught and has inspired a mountain of scholarly commentary. Despite the difficulty of his style, he is also popular among students.

Hopkins is one of the great Christian poets of the modern era. His verse is profoundly, indeed almost totally, religious in subject and nature. A devout and orthodox convert to Catholicism who became a Jesuit priest, he considered poetry a spiritual distraction unless it could serve the faith. This quality makes his popularity in our increasingly secular and anti-religious age seem paradoxical. Yet the devotional nature of his work may actually be responsible for his continuing readership. Hopkins’s passionate faith may provide something not easily found elsewhere on the current curriculum – serious and disciplined Christian spirituality.

The history of English poetry is inextricably linked to Christianity. As Donald Davie commented in his introduction to The New Oxford Book of Christian Verse (1981), “Through most of the centuries when English verse has been written, virtually all of the writers of that verse quite properly and earnestly regarded themselves as Christian.” Not all poetry was explicitly religious, but Christian beliefs and perspectives shaped its imaginative and moral vision. The tradition of explicitly religious poetry, however, was both huge and continuous. Starting with Chaucer, Langland, and the anonymous medieval authors of The Pearl and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, religious poetry flourishes for half a millennium. The tradition continues robustly through Donne, Herbert, Vaughan, Traherne, Cowper, Milton, Blake, Wordsworth, Tennyson, both Brownings, and Christina Rossetti – as well the hymnodists Watts, Cowper, and Wesley. Then in the middle of the Victorian era it founders. Matthew Arnold’s melancholy masterpiece of anguished Victorian agnosticism, “Stanzas from the Grande Chartreuse” (1855) exemplifies the crisis of faith. Entering the ancient Alpine monastery, Arnold contrasts the millennium of faith it represents with his own unsatisfying rationalism. Arnold articulates his intellectual and existential dilemma: “Wandering between two worlds, one dead, / The other powerless to be born.”

Not coincidentally, it was during that moment of growing religious skepticism and spiritual anxiety that Hopkins appeared to transform and renew the tradition of Christian poetry. Consequently, he occupies a strangely influential position in the history of English-language Christian poetry. His audaciously original style not only swept away the soft and sentimental conventions of nineteenth-century religious verse, it also provided a vehicle strong enough to communicate the overwhelming power of his faith. His small body of work – hidden for years – provided most of the elements out of which modern Christian poetry would be born.

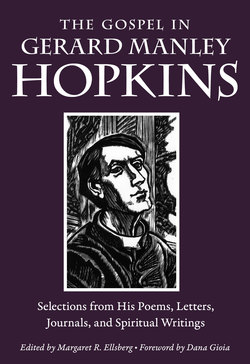

PEGGY ELLSBERG’S The Gospel in Gerard Manley Hopkins focuses on the central mystery of the author’s singularly odd career – how a talented minor Victorian poet suddenly emerged after seven years of silence as a convulsively original master of English verse. For Ellsberg, Hopkins’s conversion to Catholicism was the catalytic force, intensified by Jesuit spiritual discipline and intense theological study. Hopkins’s poetic formation, she contends, was inextricable from his priestly formation. It was no coincidence that the great explosion of his literary talent occurred as he approached ordination. His conversion had initiated an intellectual and imaginative transformation – initially invisible in the secret realms of his inner life – that produced a new poet embodied in the new priest. For both the man and the writer, the transformation was sacramental.

Although Holy Orders plays a critical role in the chronology of Hopkins’s transformation, the connections between his Catholicism and creativity do not end there. The author’s religious and imaginative conversion, Ellsberg demonstrates, depended on his vision of all the sacraments, especially the Eucharist. “For him,” Ellsberg formulates persuasively, “a consecration made from human language reversed existential randomness and estrangement.” Hopkins’s belief in transubstantiation and real presence saved him from the painful theological doubts and sentimental spiritual hungers of his Anglican contemporaries; their crepuscular nostalgia and vague longing were replaced by his dazzling raptures of light-filled grace. A brave new world filled his senses with the sacramental energy of creation where every bird, tree, branch, and blossom trembled with divine immanence.

From the start Hopkins’s literary champions have been puzzled, skeptical, confused, or even hostile toward his conversion. Catholicism was seen, even by Robert Bridges, as an intellectual impediment that the poet’s native genius somehow overcame, though not without liability. Or Hopkins’s theology was a cerebral eccentricity that generated an equally eccentric literary style. Ellsberg refutes these condescending views of the poet and the Church. She pays a great poet the respect of taking his core beliefs seriously, not in the least because they have also been both the animating ideas of European civilization and the foundational dogmas of the Roman Catholic Church, which have inspired artists for two millennia.

The Gospel in Gerard Manley Hopkins combines scholarly accuracy with critical acumen. Ellsberg’s extensive commentary on Hopkins’s verse and prose texts both elucidates his thought and provides illuminating context for the poems. Meanwhile she sustains her larger argument on the spiritual development of the author as a model Christian life of consecration, contemplation, sacrifice, and indeed sanctity. In restoring the focus on the centrality of Hopkins’s faith, Ellsberg does not simply clarify the underlying unity of his life and work. She also restores a great poet and modern saint to us, his readers.

Dana Gioia

Poet Laureate of California