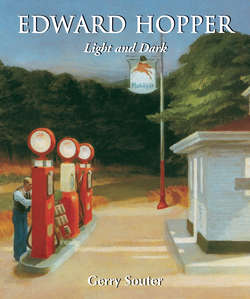

Читать книгу Edward Hopper. Light and Dark - Gerry Souter - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Emergence – a World of Light and Shadow

Paris, Impressionists and True Love

ОглавлениеIn October 1906 he chose the route most travelled by artists at that time, a journey to Paris, the world’s cultural shrine. At the age of twenty-four, the tall boy from Nyack, New York went off to “see the The elephant”. In that same month, as Hopper embarked for the French capital, Paul Cezanne died, his work only attracting attention in his later years. Of the mighty band of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters who had stood the art world on its ear, only Edgar Degas remained. He lived on in Paris, virtually blind, creating clay sculptures by touch. The public was unaware of him until after his death in 1917.

But the word had gone out and young men – and some persistent young women – with paint boxes and folding easels crowded the banks of the Seine with its bridges, the Latin Quarter and Montparnasse. They crowded the tables at the Dôme and Moulin Rouge. Prostitutes flourished. Pimps thrived and many young artists traded their talent for cheap wine and absinthe, holding down wire-backed chairs clustered around café tables littered with glassware and small saucers soiling paper table covers scratched with scribbled graffiti that would come to nothing.

Automobiles chugged and popped on spoked wheels announcing themselves with bulb-horns hooting at crossings. They added their few exhausts and their aroma of burning castor oil to the million chimneypots that sent charcoal and wood smoke into the miasma that hung above the city. Horse droppings littered the streets.

Pissoires and sewage wagons added their fragrance to each early morning, almost overwhelming the baguettes rapidly circulating in carts from bakeries to restaurants to be eaten before they turned to hard crumbly bird food. Paris was a rich stew of action, smells and grand architecture thickened with islands of leisured timelessness utterly foreign to any American brimming with the need to succeed.

On 24 October, Edward Hopper arrived at a Baptist mission at 48 rue de Lille, the Eglise Evangélique Baptiste run by a Mrs. Louise Jammes, a widow who lived with two teenaged sons. The New York Hoppers knew her through their church. As soon as Edward could manage he applied gesso ground to some 15” × 9” wood panels and set out with his paints and brushes. The colours in his box reflected the darker tones he had worked with under Henri’s tutelage in New York: umbers, siennas, browns, greys, creams, cerulean blue. His eye immediately sought out the juxtaposition of geometric shapes.

Shafts and strikes of light on surfaces gave the images depth and a dynamic of expectancy. Where there were no people, it seemed as if someone had just stepped away from a window or the last of a crowd had just passed along the deserted bridge. After years of drawing from models at school and rendering gay young people for his commercial illustration jobs, people vanished from his work except as distant compositional objects – mere dabs of the brush or people-shaped objects.

On balance, when he was not painting in oils, he sketched the denizens of the Paris streets and created a collection of watercolour caricatures from the demi-monde and the lower depths of French society. These character types were not new to him. While at school he had rented a small studio on 14th Street. Prostitutes patrolled that area with insouciant assurance.

11. Trees in Sunlight, Parc de Saint-Cloud, 1907. Oil on canvas, 59.7 × 73 cm. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Josephine N. Hopper Bequest.

12. Le Pont des Arts, 1907. Oil on canvas, 59.5 × 73 cm. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Josephine N. Hopper Bequest.

13. Le Quai des Grands Augustins, 1909. Oil on canvas, 59.7 × 72.4 cm. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Josephine N. Hopper Bequest.

14. Claude Monet, Le Pont de l’Europe, gare Saint-Lazare (The Bridge of Europe, Saint-Lazare Station), 1877. Oil on canvas, 64 × 80 cm. Musée Marmottan, Paris.

In his letters home he mentioned the grace of the French women and the stunted appearance of the men. After the grimy chaos of New York, however, Paris seemed clean and inviting. Dressed in his tailored suit, shirt and tie, and topped with a straw boater when weather permitted, he spent much time wandering in the parks, down the tree-lined paths of the Jardin des Tuileries, listening to bands play in the gazebos and watching children sail their boats in the fountain. While the Hoppers’ home life had maintained a placid surface, and displaying emotions in public had been frowned upon, Paris must have seemed like an open candy store to the repressed young artist.

Hopper had little tolerance for the famous pavement cafes along the boulevard du Montparnasse and the boulevard Saint-Germain. There, in the words of Patricia Wells of the New York Times, “…the café serves as an extension of the French living room, a place to start and end the day, to gossip and debate, a place for seeing and to be seen. Long ago, Parisians lifted to a high art the human penchant for doing nothing.”[5]

He did manage to sit in on some of Gertrude Stein’s famous salons peopled with the Old Guard and the avant garde: novelists, painters, sculptors, poets and wealthy expatriates following “the season” and the parties. “I wasn’t important enough for her to know me,” he said later in an interview.

A few New York art students had preceded him to Paris and he used them to help him explore. Patrick Henry Bruce and his new wife were particularly helpful. They made sure he became acquainted with the impressionist painters who had broken out just twenty years earlier: Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley, Monet and Cezanne.

Pissarro he liked, Cezanne he didn’t, dismissing the painter’s work as “lacking in substance”. Bruce and other artists in residence led the initiate marching through the galleries where the paintings of these masters glowed on the walls and through the Gustave Caillebotte Collection at the Luxembourg Palace where that artist had saved paintings once condemned.

As spring arrived and rain washed away the grime from the skies and puddled the streets, Hopper noticed the sudden luminosity, the light reflected into shadows, how bright the stone buildings appeared. The small oil-on-board studies he had made in the earth colours he had brought from New York were set aside as the sun suddenly suffused his work. Into a series of 25” × 28” canvases he poured light-bathed scenes of Paris and its suburbs, and followed the Seine and nearby canals where wash boats (laundry washing) tied up for customers.

In Le Louvre et la Seine, the great repository of art shimmers in gold beyond two wash boats tethered in the Seine. Terraced lawns in Le Parc de Saint-Cloud are slabs of yellow-green pierced by up-thrusting tree trunks into a hot thick impasto sky.

The Impressionists loaded his palette with both hands when he produced Trees in Sunlight at that same Parc de Saint-Cloud location. Here his brush strokes shortened up, becoming busy dabs of alizarin, both raw and mixed with zinc white. Trees became vertical slashes and swipes of thalo green and cadmium yellow. The indoor school studies faded away as he attacked his sky-lit subjects, painting from life.

The sketchy nature of these Paris oils and watercolours seemed to bubble through the architectural geometry of Hopper’s developing style as though he was channeling the spirits of dead Impressionists. Sadly, the very “European” nature of the subject matter and its handling ran contrary to the gritty realism happening back in the United States.

By 1907 he was having a grand time, as letters from the widow Jammes revealed to Hopper’s parents. He was a fine “mama’s boy,” enjoying good wholesome fun while ignoring the slovenly Bohemian art scene. And then he met the first true love of his life. Her name was Enid Saies.

“I went to dinner at an English chapel…with a very bright Welsh girl, a student at the Sorbonne, and we derived considerable amusement from the evening’s programme, which consisted chiefly of sentimental songs with the h’s omitted.”[6]

She also boarded with the Jammes. Her parents, like Edward’s, were very religious and she, like Edward, cared little for religion. Enid was not Welsh, but her parents were English with a house in Wales. Being very bright, fluent in French and other languages and a book lover, she must have dropped into Hopper’s austere well-ordered life like a bombshell. She was also tall at 5 ft 8 in with dark brown hair and light brown, almost hazel eyes.

With her English accent, possibly spiced with a bit of a Welsh lilt, and her enjoyment of his awkward sense of humour and American habits, he became enraptured. Her studies at the Sorbonne had concluded and she was preparing to return to England in the summer. Worst of all, she had accepted the marriage proposal of a Frenchman ten years her senior.

Edward wrote to his mother that he wished to extend his trip to Paris into a tour of Europe as he was already in France. With parental assent – blindly given and not knowing his reason was the pursuit of Enid – Hopper packed and crossed the Channel to Dover and took the train to London.

There he trudged around the English capital, finding the Thames “muddy,” the city “dingy” and the culture lacking the sparkle of France. Dutifully, he climbed the steps to the National Gallery and the British Museum. He wrote home that the food could not match the quality of that served in France. But nothing could match the love he had left behind and he made one final try to change that situation.

Hopper took Enid out to dinner. He sat with her in her parents’ garden and, as she told her daughter years later, told her of his love and his desire to marry her. She remained true to her fiancé.

In the end, Hopper left London for Amsterdam, Haarlem, Berlin and Brussels on 19 July without unpacking his brushes or sketch pad. When he returned to Paris on 1 August 1907, the city had emptied because all its residents who are able to flee the August heat. And the City of Light held too many fresh memories. On 21 August he sailed for the United States, anxious to make use of his experiences and begin the campaign to make a name for himself in the world of fine art.

Later, Hopper wrote to Enid and she replied in depression over her impending marriage and reminding Edward of their great times together. “I’ve made a hash pretty generally of my life…oh, I’m so miserable…”[7] If this was a plea for Edward to come to her rescue, it fell on scorned ears. He was not used to rejection. She eventually abandoned her French suitor, married a Swede and raised four children. Back home in New York, Edward Hopper was discovering real rejection had many faces.

15. Le Bistrot or The Wine Shop, 1909. Oil on canvas,

59.4 × 72.4 cm. Whitney Museum of American Art,

New York, Josephine N. Hopper Bequest.

5

Patricia Wells, Where to Sit to See and be Seen, New York Times, 6 June 1982

6

Edward Hopper, Letter to his Mother, 29 December 1906

7

Enid M. Saies to Edward Hopper, letter, Derby, England, 1907