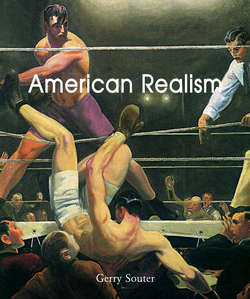

Читать книгу American Realism - Gerry Souter - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Thomas Eakins (1844–1916)

ОглавлениеThomas Eakins, The Champion Single Sculls (Max Schmitt in a Single Scull), 1871.

Oil on canvas, 81.9 × 117.5 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York, the Alfred N. Punnett Endowment Fund and George D. Pratt gift.

Thomas Eakins was a brilliant artist, but a failed human being. He brought the realism skills of the European salon painter to the American scene, but left behind the scattered detritus of a rather cruel and sordid lifestyle. He had a gift for technique and capturing emotion on canvas, but some of the emotions he captured were the result of his reclusive and demanding personality. On the one hand, his contemporary cronies and colleagues thought him a fine fellow, if a bit overbearing and driven. The personal side of his relationships with women and relatives and many of the people he painted was littered with sorrow, suicides and madness. Despite the dualism of his nature, he emerges as one of the most influential and important American Realist artists of his era.

Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (pronounced “Ache-ins”) was born on 25 July 1844 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which eventually became his sole base of operations. He was a painter, photographer and sculptor. His parents were his Dutch-English mother, Caroline Cowperthwait and Benjamin Eakins of Scots-Irish ancestry. His father was the son of a weaver and took up calligraphy and the art of fine copperplate writing. He moved from Valley Forge to Philadelphia to pursue that trade. Thomas was their first child and by the age of twelve he admired the exactitude and precision required to produce calligraphic script and printing. This early exposure to careful planning and diagramming images stayed with him and became an important part of his creative method.

His love of the physical sports he later painted, rowing, ice skating, swimming, wrestling, sailing, and gymnastics also began in his youth. His academic life started in Philadelphia’s Central High School, the finest school in the area for applied sciences and both practical and fine art. Eakins maintained his consistency by settling into mechanical drawing. In his late teens, he shifted to the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts to study drawing and anatomy and then expanded his anatomical studies at the Jefferson Medical College from 1864–65. Though he started out following his father into calligraphy and becoming a ‘writing master’, his studies in anatomy had motivated him towards medicine and surgery. The quality of his drawing, however, earned him a trip to Paris to join the classes of the classic salon academician and ‘Orientalist’ painter, Jean-Léon Gérôme.

A superb technician, Gérôme was one of three painters allowed by the Emperor Napoleon to open a Paris atelier with sixteen selected students under the reorganised École de Paris in 1864. At that time, in order to exhibit at the salons where patrons made their purchases, membership of either the École or Salon de Paris was mandatory. Gérôme was an ‘historical genre’ painter given to the romance of historical anecdotal works and costumed models that were more mannequins for the costumes and props than character studies. The fold of a silk dressing gown on a bare-breasted young lady, or the realistic curl of smoke from an exotic hookah pipe, were as prized for commercial success as the emotional content of the picture’s theme. The training in these effects as well as the chemical properties of the paints and endless drawing from plaster casts was rigorous.

Eakins eventually moved on to the atelier of Léon Bonnat, whose pupils also included Gustave Caillebotte, Georges Braque, Aloysius O’Kelly, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Bonnat had a love for the anatomical precision of da Vinci and Ingres, which resulted in works of exceptional craft and technique, but lacking in imagination. Eakins made the most of his own anatomical studies in Bonnat’s classes. His Paris schooling also included classes at L’École des Beaux-Arts, which having had its ties to the French government cut in 1863 offered painting, sculpture and architecture to a broad, more diverse cross-section of artists. Some of those who had classes there included Géricault, Degas, Delacroix, Fragonard, Ingres, Monet, Moreau, Renoir, Seurat and Sisley.

Thomas Eakins, Starting Out After Rail, 1874.

Oil on canvas, 61.6 × 50.5 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts, The Hayden Collection – Charles Henry Hayden Fund.

Thomas Eakins, John Biglin in a Single Scull, c. 1873–1874.

Oil on canvas, 61.9 × 40.6 cm.

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut.

Eakins chose to ignore the radical Impressionists, but he also turned away from the ponderous French academicians such as Gérôme and Bonnat. In a letter to his father in 1868 that predicted some of his future difficulties, he wrote:

“She [the female nude] is the most beautiful thing there is in the world except a naked man, but I never yet saw a study of one exhibited… It would be a godsend to see a fine man model painted in the studio with the bare walls, alongside of the smiling smirking goddesses of waxy complexion amidst the delicious arsenic green trees and gentle wax flowers & purling streams running melodious up and down the hills, especially up. I hate affectation.”[10]

Truth and beauty – in the form of the nude – became almost inseparable to him as he learned to render flesh and anatomy with great precision. This proclivity for wedding the two concepts raised its head a number of times in socially unacceptable (in nineteenth-century terms) events during his career.

From Paris, he travelled to Germany, Switzerland and Italy, ending up in Spain to study the realism of Velázquez and Jusepe de Ribera in the Prado. While there he tried his hand at a large canvas, A Street Scene in Seville. The painting of three street performers displays at once Eakins’ independence of mind by depicting two of the performers playing the horn and drum sitting in the shade of a scarred stucco wall while the young girl dancer stands forward in the sun on the brick street. The sun strikes her white dress and barely glances off her accompanists. His use of light and shadow gives the picture a captured immediacy of a quick photographic visualisation – another prediction of things to come.

His tour of Europe and subsequent studies seemed to fix his artist style in amber as he tossed aside the works of the Old Masters in a letter to his sister Frances: “I went next to see the picture galleries. There must have been half a mile of them, and I walked all the way from one end to the other, and I never in my life saw such funny old pictures. I’m sure my taste has much improved, and to show, I’ll make a point never to look hereafter on American Art except with disdain.”[11]

Having already dismissed the Impressionists Monet, Degas, Seurat and Renoir and the growing ‘modern’ movement, all that were left were the academicians: Gustave Doré, Ernest Messonier, Thomas Couture and his teachers, Gérôme and Bonnat. From them he had amassed an impressive arsenal of flashy techniques and a definite aversion to their commercial success with historic and romantic anecdotes. Style wise, he had gleaned from Velázquez a love of the Baroque.

This seventeenth-century art form had dealt primarily with religious works, but populist paintings using ordinary people – much like the Russian icons showing plain villagers engaging in traditional religious ceremonies – appeared from the likes of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio and Diego Velázquez. Eakins might have seen Dinner at Emmaus at the Prado, which shows a serving girl gathering dishware that would be used in Christ’s Last Supper. The artist’s choice of painting a serving girl instead of the gathering disciples in the next room carries the ring of truth and brings the ordinary person closer to the religious event. Velázquez’ use of chiaroscuro and the window light touching the girl’s cap, pots and jugs strengthens the realism and reinforces the populist inclusion. This Baroque interpretation tapped into a trend showing up in American art that Eakins discovered when he packed his bags and returned in July 1870. But in Eakins’ hands, the Baroque of the seventeenth century and fidelity to the observed or imagined scene created by Velázquez would take on a definite American character.

“I shall seek to achieve my broad effect from the very beginning,” he declared.[12]

Thomas Eakins, The Swimming Hole, c. 1884–1885.

Oil on canvas, 69.8 × 92.7 cm.

Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

Thomas Eakins, Between Rounds, c. 1898–1899.

Oil on canvas, 127.3 × 101.3 cm.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, gift of Mrs. Thomas Eakins and Miss Mary Adeline Williams.

Eakins retuned to Philadelphia and opened a studio on Mount Vernon Street. The location was only a short distance from the three-storey brick home his father had built at 1729 Mount Vernon Street, a tall narrow, deep building that housed a warren of rooms and curiously-placed stairways that became symbolic of the lives that were lived out beneath its roof. Allowing for brief sojourns, the structure became his anchor, refuge and claustrophobic dominion for the rest of his life. The house had a constantly shifting population including friends, cousins, nieces and nephews, wives and husbands, servants and babies. The world was kept out behind closed shutters summer and winter. Heat came from fireplaces and there was no plumbing, so water for all uses had to come from a hand pump in the back yard. Walls were painted in dark chocolate shades and decoration followed the usual chaotic Victorian pattern of overstuffed pieces, drapes and brasses needing a good polish. The air was musty, warm and rank with the smells of bodies, bedclothes, cooking, gas from lighting fixtures, wood ash and the lingering piquant scent from under-bed porcelain ‘thunder-jugs’ used in the night rather than make a trip over cold floors to the privy. Add to this a small zoo of animals: Bobby the monkey, dogs and at least one cat, all scampering and thrashing up and down stairs, in and out of rooms with their human internee counterparts.[13]

Eakins began his assault on fame right away with his painting Max Schmitt on a Single Scull – a man bare to the waist sitting at the oars in long narrow racing scull boat on a bend of the Schuylkill River. He looks back at the viewer as though a photographer had just hollered across, “Smile!” He is down river from a Roman-style stone-arched lift-bridge. Sports intrigued the artist and he went on to explore rowing with a series of paintings on the subject. True to his academic roots, Eakins produced a number of perspective plans, studies and sketches prior to execution of the oil. The final picture had the feeling of not being seen as a piece, but assembled from many different observations. This practice became an immutable standard. He went beyond the empty detail-saturated decorations of the academic realists to the application of their skills plus his own knowledge derived from meticulous observation. In exercising this conglomeration of observations and details, he did what good writers attempt – he edited out what was unimportant. As Ernest Hemingway once said of his craft, “What you leave out is as important as what goes on the page.”

A watercolour titled The Sculler became his first sale in 1874 and critics who saw his assembled rowers were unanimous in their praise. His friend and fellow painter Earl Shinn introduced Eakins to the public in the magazine Nation in 1874 when he wrote: “Some remarkably original and studious boating scenes were shown by Thomas Eakins, a new exhibitor, of whom we learn that he is a realist, an anatomist and mathematician; that his perspectives, even of waves and ripples, are protracted according to strict science…”

That same year also heralded his engagement to Katherin Crowell, the sister of Will Crowell, who was married to Eakins’ sister, Frances. The ‘engagement’ lasted from 1874 to 1879 and Eakins felt no obligation to consummate the relationship. It is suggested that the young woman was pressed upon him by his father, the family patriarch. In any case, she died of meningitis in 1879 leaving Eakins free to select and marry an up-and-coming artist, Susan McDowell, in 1884.[14] She eventually gave up her art career to clean house for Eakins and the live-in menagerie. His idea of marriage, it turned out, was not a love match, but the need for a healthy woman to breed and bear his children.

The year following his engagement to Katherin Crowell, he painted the work that is today considered the pinnacle of his career, The Gross Clinic. It is a large oil showing the removal of a dead piece of bone from an anaesthetised man by a number of doctors in dark suits with blood on their white shirt cuffs in the operating theatre presided over by Doctor Samuel Gross. In the background, the wife of the man under the knife cowers in horror with her face away from the action and her hands in claw-like reaction. By today’s standards it is a mild enough scene, but in Victorian Philadelphia, those red gobbets of blood on the surgeon’s fingers and the scalpel blade caused revulsion. Dr. Gross, a dignified gentleman, is spotlighted with a deeply shaded face, his glowing dome of a forehead surrounded by a frizz of unruly grey hair, his mouth an unfeeling slit dragged down at the corners. Today, the painting is riveting and dynamic as well as heaped with Freudian pronouncements concerning Eakins and his relationship with his domineering father. In 1875, nobody wanted the thing, but it finally sold for $200. Society retreated from the artist as a wave draws back into the sea.

Following the cool reception of The Gross Clinic, Eakins entered the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts as a teacher. He rose to the position of salaried professor in 1878 and was named a director in 1882. To his students he brought refreshing if controversial teaching methods. Harking back to his own rigorous academic studies, he banned sketching from dusty antique casts – the standard of the time – and following a brief introduction to charcoal sketching, his students plunged directly into painting in colour. At this time, he introduced photography as an artist’s aid.

Photography had arrived from M. Daguerre in France about the same time Eakins was born. By the 1880s, it had been refined from a slow chemical-optical nightmare into a common hobby and documentation tool. Thanks to Richard Leach Maddox, photographs were made on a dry glass plate coated with silver bromide suspended in gelatin – negatives were no longer made on freshly coated wet plates that had to be developed immediately after exposure. This development allowed for portable full (20.3 × 25.4 centimetres), half (12.7 × 17.8 centimetres) and quarter (10.2 × 12.7 centimetres) plate cameras to be used by anyone. Film was exposed in plate holders by the lens and shutter to be developed later in a darkroom lit by a dim ruby-red lamp. Eakins obtained his first camera and took his first photograph in 1880. He also discovered the photographic motion studies of Edward Muybridge. Using multiple cameras firing in sequence, the flying legs of a galloping horse or the muscular arc of a pole-vaulting man were studied to see how the anatomy functioned. Eakins was enthralled and began using photos in his work and his classes.

Photographs allowed Eakins to continue his practice of assembling a painting from many different sketches and studies, but with greater precision due to the photo’s detail. From his collection of more than 800 photos, many were used to add elements to paintings by tracing the captured action and transferring the pencil tracing on see-through paper with a rubbing on the paper’s opposite side. His photographing of nude figures in his classroom was usually done in the presence of a chaperone if young women were involved. He photographed his wife and his nieces who frequently scurried about the house naked and continually pestered female relatives to undress and pose. No other artist of his time made such a broad use of photography in his work and studies. Their constant display in his classroom probably had something to do with his later difficulties with the Philadelphia Academy.[15]

This broad-based acceptance extended to the students accepted for his training. He did not distinguish between fine art and practical arts. He welcomed illustrators, lithographers, decorators and other applied artists as long as they took their work seriously. This ‘serious’ approach to art included joining in his appreciation of the nude figure. His classes included both male and female students and they viewed a constant parade of nude models in this era when a glimpse of a female ankle was considered scandalous. Eakins also delighted in leading his male students out to remote locations where everyone disrobed – including Eakins – and cavorted in sports and games or simple contemplation while sketches or photographs were made for future reference.

In one instance, he talked a sixteen-year-old boy into climbing up to the Eakins’ house rooftop and posing nude, save for a loincloth, on a cross for the painting Crucifixion. In this work, Eakins managed to show the event, a young man dying in the sun, minus any religious overtones. The neighbours were sure the body was a corpse.[16]

Eakins managed to accumulate a large collection of nude photographs of men and women featuring full frontal nudity. In his portraits of his female relatives he was almost always at them to pose naked or to shed some of their layers of clothing. This nagging often went on during the painting session and accounts for the wearisome expression on the faces of many of his female sitters. Sometimes the portraits were rejected or taken home and put in a cupboard.[17]

Thomas Eakins, Taking the Count, 1898.

Oil on canvas.

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut.

Thomas Eakins, The Agnew Clinic, 1889.

Oil on canvas. 214 × 300 cm.

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Thomas Eakins, Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic), 1875.

Oil on canvas, 243.8 × 198.1 cm.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Thomas Eakins, Self-Portrait, 1902.

Oil on canvas, 76.2 × 63.5 cm.

National Academy Museum, New York, New York.

Never the prude and always willing to help, when a female student, Amelia Van Buren, requested some instruction as of the movement of the pelvis, Eakins promptly dropped his trousers to show her how his pelvis moved: “I gave her the explanation as I could not have done by words only.”[18]

This parade of naked people through his life, work and teaching culminated in his casual act of whipping away the loincloth from a male model in his class in front of attending female students. This rude demonstration, plus a litany of accumulated complaints from students and faculty, got him fired from the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts. He was devastated. Some of his loyal students quit the academy as well and created the Art Students League of Philadelphia where he did some instructing, but a great depression swept over him. At home, a collection of his relatives rose up against him as well. A student, Lillian Hammitt, who claimed she was his wife, was hauled away to a mental institution in 1888. His mother had died in 1872 of a consuming mania and later, another young lady, Eakins’ repressed niece, Ella Crowell at the age of twenty-three blew her head off with a shotgun. Family members all pointed at Eakins because of his surly attitude and often eccentric habits. Because of a lack of primary resource material – Eakins wrote very few letters in his lifetime and kept no diaries – all accusations are speculation or second-hand declarations. Eakins refused to even display his growing number of unsold paintings, keeping them stacked against the wall of his studio.

On the recommendation of Dr Horatio C. Wood, a professor of nervous diseases, Thomas Eakins fled to North Dakota and lived on the B-T Ranch in Little Missouri Territory of the Badlands. In the wide-open spaces, he thrived.

Eakins scholar Elizabeth Johns, PhD writes of his stay: “So he was at a very low ebb when he came out here. And I think what this experience gave him was a vital contrast to the constricting landscape of Philadelphia. This was a sanctuary that he would remember. A largeness of the physical universe. A hardiness of the characters that made their living on this soil that would inspire him the rest of his life.”[19]

His enthusiasm for the rugged life and its restorative powers come through a letter to his wife, Susan: “Dear Sue, Only last fall a horse thief was shot full of holes a few miles north of here and fall before last they hung one… While I was holding down the ranch I had all the chores to do: milking the cows, cleaning the stables, watering and feeding stock, etc. On the second day the twin calves broke out of the stable. I tried to shoo them in but they wouldn’t go. Then I ran into the stable and picked up the first rope I saw and made a loop and tried to catch one. The rope was too short and mean and I couldn’t get them so then I went and got my good lariat… I chased them up and down throwing at them for about an hour till I was so hot and mad I should have enjoyed branding those same calves… The boys had a good laugh when they heard how I had tried to rope the calves afoot. They got on their horses and caught them right away. I killed a big rattlesnake the other day and will bring home the rattle for Ella. My horse is the fastest of all those on the ranch… The time is more than half gone now. How happy I shall be to see you again.”

His rehabilitation lasted from July to October 1887 when he returned to Philadelphia. He and his wife had been staying in a small flat near the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts and now moved into his father’s house where he ultimately became the patriarch following Benjamin Eakins’ death. To accommodate his work, he added a fourth floor to the building in the form of a faux Mansard roof and there he remained for the rest of his life. On his return, he produced a portrait of Walt Whitman, which the elderly poet favoured above all the previous attempts. Eakins would make many trips to Whitman’s home over the next years. Their friendship lasted until Whitman’s death in 1892.

His one sortie into sculpture came in 1891 when he collaborated with his sculptor friend William Rudolf O’Donovan in the creation of bronze equestrian reliefs of Ulysses S. Grant and Abraham Lincoln for the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch in Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza. O’Donovan sculpted the two human figures while Eakins created the horses.[20]

His teaching continued at various venues including: the Art Students League in New York City, the National Academy of Design, the Women’s Art School at New York’s Cooper Union, and the Art Students’ Guild in Washington D. C. By 1898, he withdrew from teaching to concentrate on his portraiture.

As before, his portraiture, especially of women, while some writers call it “revealing”, is for the most part bleak and distracted. Even the men came off as cold and distant. Their clothing always seemed to need a good ironing. In fact, he often asked his sitters to pose in old clothes rather than their finery. This is a contemporary view, but considering the portrait standard of the time where the client was considered a patron as well as an object and treated with kindly flattery – whether deserved or not – Eakins’ images did not please many of his sitters.

Though he carried a disreputable taint, honours came his way: The Chicago Exposition of 1893 awarded him a gold medal. He received other medals from the Universal Exposition in St Louis, a bronze medal from the Exposition Universal in Paris, the Proctor Prize from the National Academy of Design, the Temple Gold Medal awarded by the Pennsylvania Academy, a gold medal from the American Art Society of Philadelphia and the Second Class Medal presented by the Carnegie Institute. But during this time he was also fired from the Drexel Institute for once again parading a nude male model in front of female students during a lecture. In 1896, he received his only one-man show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and in 1902 he was elected an Academician of the National Academy of Design.

By 1910 both his eyesight and health were on the decline. In his final years, he rarely left the house on Mount Vernon Street with its wearying collection of family tenants, assorted animals and hangers-on. With his good friend Samuel Murray – and not his wife, Susan, from whom he had become estranged – holding his hand, he died on 25 June 1916 from, it is surmised, the gradual accumulation of formaldehyde in his system. This preservative was used in milk to avoid spoilage in those days of erratic refrigeration and Eakins drank a quart of milk every day at dinner.

The love-hate relationship with the evolving art world continued after his death. In 1917 both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Art hung his work in memorial retrospectives. Still later a number of biographies surfaced that emphasised the quality of his work over his rather sordid lifestyle and its obsessions and homoerotic fixations. The value of his work was significantly elevated and his personal relationships idealised.

In 1984, a large collection of Eakins’ papers came to light. They had been hidden by one of his pupils, Charles Bregler, after the artist’s death in 1916 and they re-emerged in the possession of his widow Mary in 1958 following his death at the age of ninety-three. Since then, a more balanced look at Thomas Eakins’ life has been possible.[21] No one can take away the value of his work in the tradition of American Realism. Understanding his numerous frailties, however, adds a dimension to appreciating what survives on canvas and in photographic prints.

Thomas Eakins, Singing a Pathetic Song, 1881.

Oil on canvas, 114.3 × 82.5 cm.

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D. C., Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund.

10

William Innes Homer, Thomas Eakins: His Life and Art, Abbeville Press, 1992, p. 36

11

Lloyd Goodrich, Thomas Eakins, His Life and Work, Vol.1 Ams Pr. Inc., June 1977, p.27

12

H. Barbara Weinberg, Thomas Eakins, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001

13

Henry Adams, Eakins Revealed – The Secret Life of an American Artist, Oxford University Press, New York, 2005, pp. 3–5

14

Ibid, pp. 36–38

15

Jeff L. Rosenheim, “Thomas Eakins, Artist-Photographer, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art” in Thomas Eakins and the Metropolitan Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994, p. 45

16

Edward Lucie-Smith, American Realism, Harry Abrams, Inc. New York, 1994, p. 35

17

Ibid

18

Homer, op. cit., letter from Eakins to Edward H. Coates, September 12, 1886, p. 166

19

Elizabeth Johns, (PhD, Art Historian University of Pennsylvania), Thomas Eakins: Scenes from Modern Life, PBS (http://www.pbs.org/eakins)

20

Darrel Sewell, Thomas Eakins: Artist of Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1982, p. 78

21

Adams, op. cit., pp. 42–43