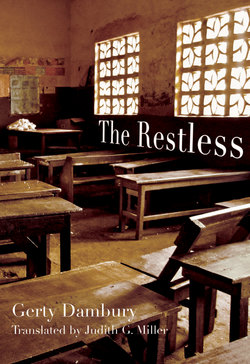

Читать книгу The Restless - Gerty Dambury - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1.

Émilienne is seated on her small bench, the one that actually belongs to our mother.

The small one for doing laundry in the courtyard.

The child has taken over the bench, the courtyard, even the night.

She is waiting for her father—our father.

She’ll wait all night long if she has to. She won’t cease her vigil until he comes home.

Not worth trying to chase her away. No way, not a chance.

That child has been worrying us for three days now: sudden tears, mood swings, a whole armory of whims.

She’s put us through the wringer, and today, just as our city is descending into riots no one saw coming, her attitude is, frankly, pushing us over the edge.

This afternoon, in the streets of Pointe-à-Pitre, gunshots followed billy-club blows, bodies of the dead and wounded formed a path right up to the hospital just north of our house, and the child was right there in the middle of it.

She disappeared for the entire afternoon and didn’t go to school.

What was she doing? Where on earth did she go and why? We’d certainly like to know!

She returned home unharmed, and for that, we thank God. But now, one whim has replaced another.

She’s set up shop in the courtyard, refusing to leave until our father explains to her how in 1967, on May 26, a massacre was able to happen and especially . . . Especially why her schoolteacher has disappeared.

Yes, that second explanation is the most important to her.

To think about her sitting on that small bench all night long, in the dark—and of course she won’t let one of us sit next to her—well, it’s not reassuring.

All those shadows and unhinged souls wandering around at night will slip into the courtyard, no question about that.

We’re sure of it because the child enjoys holding strange conversations with shadows we don’t see.

Up until now her whispering made the whole family smile.

To us it was merely a child’s game.

But now, here she is speaking to the dead, people we recognize perfectly, as if this afternoon’s butchery had awakened from the depths all those who’d been sleeping. Émilienne is speaking to our old neighbor Nono, who exited the world of the living some two years ago.

She also whispers to Uncle Justin, “Come on in, Uncle Justin.”

And we tremble.

We also hear our little sister speak to ma-commère or “Mademoiselle Pansy,” one of our neighbors, a scorned homosexual, dead as well.

You can be sure all these folks will add their two cents to the turbulent events of May 26.

After all, someone has to make sense of it.

Someone’s voice ought to give clear shape to this story, a story that should be told the way a caller calls out a Caribbean quadrille, in which each of the figures gracefully follows the preceding one:

First, pantalon

Second, l’été

Third, la poule

Fourth, pastourelle

We need a strong caller with a powerful voice, so we will be that caller—us, Émilienne’s eight brothers and sisters.

We’ll give the floor to the one who should speak, just as though speaking were dancing.

We alone will decide how many steps to the right or left each one can take. We’ll decide when a dancer or a group of dancers need to leave the floor to make room for the next, or at what point a musical instrument will take up the story or add its sounds to another’s melody in order to emphasize a phrase, mark a refrain, or signal the moment to change rhythm.

No, wait! We’ll leave the signaling of the tambourine to Émilienne! Let her be the one to call out the changes, to play the tanbou d’bas that accompanies our square dances.

You say there’s never before been a group of callers in a square dance?

Never seen until now, you say!

Then we’ll innovate.

And every musician, dancer, or character—depending on whether you think we’re in a novel or a dance—will become an interpreter.

We’ll start with the waltz. A slow waltz, a good start, an introduction.

Let’s innovate! And let’s hand the waltz over to the child.

Because, you see, who better than Émilienne to get all this going?

She’s still surprisingly calm after everything she’s been through.

And she’s always had this quirkiness, an obsession with repeating the same phrase over and over again, like a special mantra: “I have no name. I have no face.”

We even used to wonder if the child wasn’t a little crazy.

But maybe, maybe, she really does live in another world.