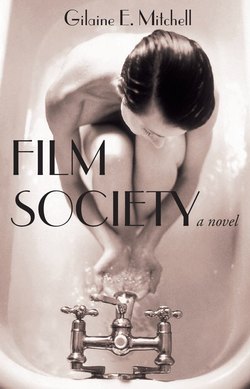

Читать книгу Film Society - Gilaine E. Mitchell - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One

ОглавлениеThis tree-lined street with Victorian homes and large front porches could be any street in any small Ontario town. It just happens to be in the Village of Stirling, where a group of women meet once a month in the red brick house at the end of Anne Street to watch movies.

It started one winter night, upstairs in my bathroom. Jenny was sitting on the edge of my tub, which badly needed caulking, while I was busy smearing deep red all over my mouth. She was telling me caulking isn’t so hard, the trick is to make sure you tape it in, and don’t stop once you start spreading the white goop.

“If you stop, you’ll fuck it up. You’ll get blobs,” she said from behind me.

I removed half of my lipstick with a soft bite on a single square of toilet paper then flushed it down the toilet. Jenny inspected my tub, pushed a small piece of loose caulking back into place and advised me on what type of caulking I should buy.

“Don’t be cheap,” she said. “It’s never a good idea to skimp on good caulking. You’ll just end up with that black mould again before you know it.” Then she sat on the toilet to pee, told me I should tighten the wooden seat before someone falls off and breaks their neck, and asked me how much toilet paper I buy in a week. I sat on the edge of my tub, closed the curtain behind me to block out the mould and the maintenance and my impatience with perfection.

I’ve never had much luck with bathrooms.

I’ve anticipated many happy endings in bathrooms. I’ve made love in bathrooms. Changed my mind in bathrooms. Can’t forget some bathrooms. Like the one at the Legion with the bad paint job, where I saw my aunts reapply their makeup and discard their disappointment, where I followed suit and made my way back out to the dance floor to waltz with a man I no longer loved.

I’ve washed away the semen of men I barely knew in bathrooms I saw only once, where cold, grey water lay in puddles on Formica counter tops and football-shaped soaps hung on thick ropes over the shower head — honestly, I didn’t know they were there until it was too late — either that, or there was nothing anywhere but a few sheets of toilet paper dangling from a broken holder and a black towel hung in a hurry over the curtain rod, tiny hairs all over the floor.

One bathroom saw me through infidelity and the birth of my children, where I soaked my swollen, cut, and stitched vagina in the same tub I soaked my leaping heart, hiding the aftermath of lusty afternoons with Johnny Marks behind plastic curtains, burying my post-natal state of panic in porcelain and hot water, a cluster of candles burning in the corner by the faucet.

I watched shadow flames flicker larger than life all around me as I soaked my pride the day my husband told me he was leaving, he’d found somebody else. I already knew anyway. I recognized that euphoric look, the sudden lift in his spirits, which didn’t come from being with me, but until he said it, I could ignore it. I could tell myself he wouldn’t do it, couldn’t do it, couldn’t leave, like I couldn’t, wouldn’t, didn’t. But he did.

I got over it in the bathroom.

In the bathroom, you mourn and you celebrate and you start over. Film Society began during a pee break in the middle of My Left Foot, with Jenny on the toilet, myself on the edge of the tub and then in the mirror, pinching cheeks that seemed pale and puffy, which I blamed on too much drink and not enough air — the hazards of winter hibernation.

“You should fix that leaky faucet,” Jenny said from the other side of the room. “How much do you pay for water every month? Would it be okay if I brought along a friend the next time we watch a movie?”

That winter, two of us grew into four of us, which grew into seven of us altogether. Seven women, a television, and one bathroom.

We gather every month around the table in my living room and fill up on guacamole and Grace’s stuffed pumpernickel and Alex’s homemade salsa, then wash everything down with generous amounts of wine and beer and ice water as we hastily catch up on each other’s lives. There’s always some urgency to this, to get it in before we start a film. We squeeze and condense and talk quickly — anything to bring our stories up-to-date, to say this is where I am now. And every once in a while, our own lives make us forget about the ones waiting for us in the cassette on top of my television and it’s nearly midnight before we sit down to watch.

Somewhere along the line, I became keeper of the Film Society stories, most of them told to me in further detail in first person, in a quiet corner of my cluttered kitchen, or in the privacy of my small and somewhat dysfunctional bathroom. The faucet in the sink is still leaking. The toilet seat is missing a bolt now and hangs off to one side.

My film friends don’t expect my bathroom to be any other way, but they do expect me to keep their story lines straight, to guess at what will happen next, to remember what went wrong before. They expect me to be truthful, but on their side.

It was Del who suggested our lives might be better if we had rushes or dailies to look at — the uncut film printed for viewing by filmmakers the day after it’s shot; the object is to check for errors before the set is taken down. Everyone agreed even that’s too late to change what has taken place. We’re not living celluloid lives where life comes at us in carefully crafted scenes and builds to a contrived climax and fitting resolution. There is no paradigm at work here, no guaranteed formula to follow or tell us how our story’s going to turn out. A moment simply comes, then leaves you with the rest of your life to live with it.