Читать книгу The Mystery of the Skeleton Key - Гилберт Честертон, Лорд Дансени, Гилберт Кит Честертон - Страница 5

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеAll authors, especially fiction writers, have to tread at some time on the edge of the dark slope that leads to obscurity. Some are unlucky enough to miss their step while still alive; many more slide down after their death. Such an unfortunate was Bernard Capes, who published 40 books (in 20 years) but passed into the shadows within three years of dying. He deserved better.

Bernard Edward Joseph Capes was born in London on 30 August 1854, a nephew of John Moore Capes, a prominent figure in the Oxford Movement. He was educated at Beaumont College and raised as a Catholic, though he later gave that up and followed no religion. His elder sister, Harriet Capes (1849–1936) was to become a noted translator and writer of children’s books.

Capes had a string of unsuccessful jobs. A promised Army commission failed to materialise; he spent an unhappy time in a tea-broker’s office; he studied art at the Slade School but, despite a lifelong enjoyment of painting and illustrating, it did not result in a career.

Things picked up for him in 1888 when he went to work for the publishers Eglington and Co., where he succeeded Clement Scott as editor of the magazine The Theatre.

At this point in his career, he made his first attempts at novel writing, publishing two under the pseudonym ‘Bevis Cane’: The Haunted Tower (1888) and The Missing Man (1889), the latter published by Eglington. They did not do well enough for him to use the ‘Bevis Cane’ name again.

Eglington and Co. went out of business in 1892 and Capes was up against it. Among his various ventures was a failed attempt at, of all things, breeding rabbits.

At last, aged 43, Capes found his true vocation. In 1897 he entered a competition for new authors organised by the Chicago Record. Capes came second with his novel The Mill of Silence, published in Chicago the same year.

He entered the competition again in 1898 when the Chicago Record repeated it. Capes hit the jackpot. His entry, The Lake of Wine—a long, macabre historical thriller about a fabulous ruby bearing the name of the book’s title—won the competition. It was published that year and Capes was a full-time writer from then on.

And write he did. Out flooded short stories, articles, newspaper editorials, reviews and novels, including two more in 1898.

Bernard Capes married Rosalie Amos and they moved to Winchester, where he spent the rest of his life. They had three children. His son Renalt became a writer late in life, and his grandson Ian Burns carries on the Capes writing tradition as the author of the children’s book Scratcher.

With nearly 40 books already to his name from a variety publishers, Capes’ historical adventure, Where England Sets Her Feet, was published by William Collins Sons & Co. in April 1918, with a second book, The Skeleton Key, already under contract. The significance of this new ‘criminal romance’ to the 100-year-old publishing house was yet to be realised. Modestly publicised as ‘a story dealing with crime committed in the grounds of a country house, and the subsequent efforts of a clever young detective to discover its perpetrator’, it coincided with a burgeoning post-war fashion for detective fiction. Within a few months of its publication in the spring of 1919, a flood of unsolicited crime-story manuscripts poured into the Scottish publishers’ Pall Mall office, and Collins acted quickly to capitalise on this new-found demand for detective stories.

Sadly, Capes himself never knew of The Skeleton Key’s success, for he was struck down by the influenza epidemic that swept Europe at the end of World War I. A short illness was followed by heart failure and he died in Winchester on 1 November 1918. He was 64 and had enjoyed only 20 years of writing.

His widow organised a plaque for him in Winchester Cathedral, among the likes of Izaak Walton and Jane Austen. It can still be seen, next to the entrance to the crypt.

Capes wrote historical adventures and romances, mystery novels, crime stories and many fine short stories, a lot of them dark and sinister tales (he was quite fond of werewolves). As a great fan of Wagner, he wrote a novel, The Romance of Lohengrin, published in 1905. At his memorial service in the cathedral in 1919, the organist played Wagner in his honour.

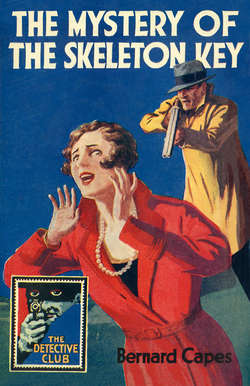

Published shortly after Capes’ death, complete with a hastily commissioned introduction by G. K. Chesterton that added to its notoriety, The Skeleton Key had already been reissued six times when, ten years later, Sir Godfrey Collins launched the company’s first dedicated crime imprint, The Detective Story Club—‘for detective connoisseurs’—a mixture of genre classics and cheap reprints. It was only natural that Capes’ book should be one of the launch titles for the new list, and so in July 1929 it appeared in its eighth edition alongside five other titles, priced only sixpence, with a dramatic jacket painting and an extended title intended to increase further the book’s popularity: The Mystery of the Skeleton Key.

By 1930, the ‘Golden Age’ of crime fiction was well underway, and Bernard Capes’ novel began to disappear as more and more inventive detective stories appeared on the market. In his 1972 book, Bloody Murder, Julian Symons called The Skeleton Key ‘a neglected tour de force’, but it’s only now, more than 40 years later, that Capes’ landmark novel has found its way back into print.

The story introduces the detective Baron Le Sage, who unravels a rather complicated murder. Le Sage is in the line of Robert Barr’s detective Eugene Valmont (who had appeared in 1906), and Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot (who was yet to be created), with a touch of Dr Fell, and is one of Capes’ most interesting creations. As one character remarks, ‘Chess is the Baron’s business.’ He might have appeared again if Capes had survived longer. It’s good to see him, and Bernard Capes, back at work again.

HUGH LAMB

February 2015