Читать книгу Italy's Sibillini National Park - Gillian Price - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

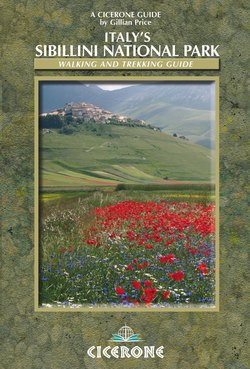

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Monti Sibillini

Little known to foreign visitors, the Sibillini, in Italy’s central Apennine chain, comprise soaring limestone mountains and awe-inspiring natural landscapes inhabited by wonderful wildlife. Rugged lofty ridges link dizzy peaks above vast bare flanks swept by howling winds. Vast grassy uplands are smothered with vivid wildflowers. In dramatic contrast, worlds below, plunging gorges are run through with deliciously cold streams. The thickly wooded valleys are dotted with utterly charming historic villages, home to herders and woodcutters, hard-working reticent folk with a great sense of hospitality. With a good 50 peaks, many over 2000m, there is plenty of exploratory walking to be done in the Sibillini on the intricate web of pathways and old cart tracks. Thanks to dedicated nature lovers and environmental activists, in 1993 this wonderland finally became the Parco Nazionale dei Monti Sibillini, encompassing 700km2.

Monte Bove Nord, GAS Stage 1

Part of Italy’s backbone, the Monti Sibillini are a narrow line of ridges that act as the watershed between the Adriatic and the Tyrrhenian seas. Straddling the regions of Umbria to the west and Marche to the east they run north–south for almost 40km. Limestone is the main constituent, formed 200 million years ago in a shallow sea and forced skywards. Glaciers later left recognisable traces such as cirques and U-shaped troughs. The stark bareness of these mountains is striking, as few trees exceed the 1500m level.

Parco Nazionale dei Monti Sibillini sign

However, much of this bareness is caused by man as dense forests of beech once cloaked the uplands. These were dramatically cut back over time to create pasture for the armies of sheep – once totalling 400,000 – key to the region’s economy.

A number of important rivers run through the range: the Nera has its source in the heart of the Sibillini and flows out through Umbria, whereas the eastern flanks give rise to the Aso, Tenna, Ambro and Fiastrone which head down to the Adriatic coast.

And the name? Sibillini glides over the tongue. In antiquity Sibyls were well known across the Mediterranean as oracles. And one such magnificent prophetess dwelt in a cavern on what is now known as Monte Sibilla, attended by bevies of gorgeous fairy handmaidens. The stuff of fairy tales. Ephemeral beings are hard to avoid in these mountains, as reflected in the place names, an entertaining mix of sacred and profane: Redeemer Peak (Cima del Redentore) and Holy Valley (Valle Santa) vs Devil’s Point (Pizzo del Diavolo) and Hell Gorge (Gole dell’Infernaccio)!

Walking

The wondrously varied landscapes of the Sibillini make for memorable outdoor holidays at any time of year, and holidaymakers of all grades of walking expertise will find something to get their boots into. There are leisurely strolls across flowered meadows and paths down eerie canyons, dizzy high ridge itineraries and a host of walkers’ peaks. This guide provides a selection of 21 day walks ranging from 1hr 30mins to 6hrs in duration, and covering the unmissable features of this region. In addition, a magnificent 8-day trek circling the Sibillini is given in detail: the GAS – Grande Anello dei Sibillini – is highly recommended and accessible to everyone, as nothing of a mountaineering nature is required. Created by enthusiasts from the Italian Alpine Club in the 1980s, it dips in and out of peaceful out-of-the-way hamlets. The objective was to offer an overall vision of the Sibillini and involve outermost villages, a superb idea. Moreover, it encourages visitors to discover that there is more to the Sibilllini than the hot spots such as Castelluccio and Gole dell’Infern-accio, where visitor numbers are huge at peak times. The GAS lends itself to numerous variations as well as detours to link up with the shorter day walks.

The Piano Grande below Castelluccio (Walk 19)

For Italian readers the landmark work is Monti Sibillini. Parco Nazionale. Le più belle escursioni. (SER/CAI 2004), by pioneers Alberico Alesi and Maurizio Calibani. This is a comprehensive guide to the park’s pathways and environmental concerns, with copious background titbits.

When to Go

Walkers can count on stepping out on Sibillini pathways from spring well into autumn, the drawn-out season being a great bonus for nature lovers and outdoor enthusiasts. The outermost, lower altitude districts such as those covered by the GAS are often accessible as early as April, though that will depend on how much snow is still lying around from winter as it can obscure important waymarks. The rifugi used on that route are owned by the park authority and are theoretically open from mid-April through to mid-October. The late spring months guarantee amazing spreads of wildflowers. On the other hand, to explore the higher ridges and routes in the heart of the Sibillini it’s best to wait until June for optimum conditions. Midsummer – August, and weekends in particular – tends to be synonymous with overcrowding at key spots such as Castelluccio and Lago di Pilato. Then too, extreme heat may be followed by thunderstorms. On the other hand, in September–October, clear crisp conditions and stable weather generally prevail, brilliant for walking. Daylight lasts until 6pm even as late as the final weeks of October, after which Italy reverts to normal time after a long summer on daylight saving time. Lastly, wintertime can be magical for exploring these mountains with snowshoes or touring skis, perhaps with a local guide.

Pian Piccolo and autumn mist (Walk 20)

Weather Notes

As the 19th-century American poet W.C. Byrant put it so adroitly in his poem To the Apennines: ‘There the winds no barrier know’. Be prepared for amazingly strong one-way winds that come howling in from the west and the Tyrrhenian coast and batter the Sibillini leaving little upright – walkers included – before heading over to the Adriatic coast. These conditions are prohibitive and to embark on ridge routes on such days is not just inadvisable but downright dangerous. A positive legacy of this nuisance is the stunning visibility and long-distance views left in its aftermath. Another meteorological phenomenon not be under-rated is mist and low cloud. This can transform even the easiest trail into a trying exercise in orienteering. What’s more, wet grass can be slippery. The Piano Grande zone is especially prone, though the upside is atmospheric photographs for those who are patient enough.

Handy meteorological websites with forecasts and webcams are www.umbriameteo.com and http://meteo.regione.marche.it/assam.

Access

Air: (See map in prelims.) For the Sibillini the most convenient places to fly into are the airports on the Adriatic coast: Ancona and Pescara are served by RyanAir (www.ryanair.com), while Rimini’s flights come courtesy of Easyjet (www.easyjet.com). A good distance inland is Perugia, another handy arrival point thanks to recent services by Ryanair. Also fairly convenient are Rome’s two airports: Fiumicino (flights by British Airways www.ba.com) and Ciampino, which is served by both the above-mentioned low cost companies. All have bus connections to railway stations.

Trains and Buses: Public transport is a wonderful way to travel anywhere as it gives a privileged insight into a different way of life and facilitates encounters with the locals. While sometimes slower and less flexible than self-driving, it means passengers don’t have to worry about missing a turn-off and are free to enjoy the wonderful scenery. Services are reliable and fares reasonable thanks to state subsidies. Last, but definitely not least, it discourages visitors from introducing more polluting vehicles into the wonderful Italian countryside. Don’t believe anyone who tells you that public transport is not feasible – this guide was researched using it! While not every corner of the Sibillini can be reached in this way, remember that most villages have someone on hand to act as a taxi driver – ask at the local café or bar. Moreover don’t hesitate to request a lift from your hotel or rifugio, as most willingly ferry guests to and from bus stops and walk starts.

Generally speaking the Sibillini are pretty well serviced by buses, though sections wholly lacking in links are the central valley between Castelsantangelo and Castelluccio, and the key road pass Forca di Presta above Arquata del Tronto. Connections between the tiny villages on the eastern flanks are not especially straight-forward either.

Train is a good way to approach the Sibillini, followed by the inevitable transfer to a bus. The railway can be used in Umbria as far as Terni on the main Rome–Florence artery (then a bus to Visso), or to Spoleto, for a bus to Norcia. In the Marche there’s the Civitanova Marche–Fabriano line: get off at Castelraimondo for a bus to Camerino (10km), a key transport hub. Further south, another branch line on the Adriatic coast reaches Ascoli Piceno.

Italian railways (FS Ferrovie dello Stato) ( 892021 or www.trenitalia.com)Beneath Monte Castel Manardo (GAS, Stage 3)The Monte Vettore ridge (GAS, Stage 6)

Contram buses ( 800 037737 or www.contram.it (click on orari for timetables)) covers the north-eastern Sibillini with year-round lines branching out from Camerino to Visso, Castelsantangelo sul Nera, Fiastra, Bolognola. Midsummer extensions include Frontignano (from Visso) and direct services to the Adriatic coast and Pesaro. Moreover there’s a handy daily run via Visso to Rome.

Mazzuca 0736 402267 or www.mazzuca.it covers the Aso valley, Montemonaco and Amandola to Ascoli Piceno.

SASP 0733 663137 links Camerino with Sarnano and Amandola.

Umbria Mobilità 800 512141 or www.umbriamobilita.it is responsible for connecting Norcia with Rome, Spoleto and Preci, as well as the Thursdays-only service to Castelluccio.

Start 800 443040 or www.startspa.it links Balzo and the Montegallo district with Ascoli Piceno.

Important note: hardly any buses run on Sundays or public holidays except in midsummer.

These terms may come in handy: giornaliero (abbreviated as G) means daily, scolastico during school term, feriale Mon–Sat, and festivo Sunday or public holidays, while sciopero is strike.

Exploring the Sibillini

The way you travel around the Sibillini will depend on how much time you have and individual preferences for walking. Visitors with no time constraints will enjoy riding the buses and meandering around the park, criss-crossing it with a combination of walking routes and staying at different places. The multi-day GAS trek is easily accessed with public transport. However, those with limited time are best using their own vehicle to cover as much ground as possible. The following notes explain the layout of the Sibillini and the facilities for visitors.

The Sibillini are embraced by an inter-connecting web of narrow valleys settled with small townships and villages. All have accommodation in the shape of welcoming hotels and cosy B&Bs as well as a restaurant or two, and make a good base for forays into the rugged mountainous core.

Beginning in the east, in the rural atmosphere of the Marche region, historic settlements dot the gently rolling slopes that begin at the foot of Monte Vettore and Sibilla and continue all the way to the Adriatic coast. The attractive red-brick town of Amandola, named for an ancient almond tree (mandorlo), is a handy gateway to the park from the northeast. It enjoys good transport links and tourist facilities, not to mention excellent mountain views from its belvedere. A short distance inland is Campolungo and Walk 5, while another detour leads to Rubbiano for Walk 9. Not far south is quiet, walled Montemonaco, founded by pioneer Benedictine monks in the very early middle ages. It stands at the foot of Monte Sibilla, at whose rifugio Walk 10 begins. The GAS trek passes close by, while a narrow side valley climbs to the mountain hamlet of Foce and Walk 15. The next notable settlement is Montegallo, actually a scatter of villages that go by this collective name. Here, beautifully situated Balzo is low key but well equipped for visitors, and acts as an alternative stopover for the GAS.

Now a winding road climbs south, high above the turrets and colonnades of landmark Arquata del Tronto on the ancient Roman artery, the Via Salaria. Veering west, this strategic road passes Forca di Presta, whose rifugio is a transit point for the GAS and start for Walks 17 and 20. A separate branch from Arquata del Tronto leads to Forca Canapine with accommodation and access to both Walk 21 and the GAS. Forking north from here, a minor road traverses the wondrous and unworldly Piano Grande to Castelluccio. This jumble of tumble-down houses occupies a hilltop belvedere that swarms with visitors during the fiorita in early June, when the lentil fields explode with wildflowers. Advance booking for accommodation is recommended then. It does have a bus service – on Thursdays – when the gregarious Castelluccio housewives ride down to Norcia for the weekly market. Walks 14, 16, 18 and 19 start at Castelluccio.

Preci cascades down a hillside (Walk 13)

Norcia is another key gateway to the Sibillini and has fine tourist facilities and good bus links. Sometimes called Nursia in English, the town’s name comes from Northia, Goddess of Fortune, venerated by the Etruscans. This relaxed, charming town is set amidst vast farming plains on the easternmost edge of Umbria. Best known as the birthplace of high profile St Benedict, founder of the Benedictine monastic movement, for Italians it is also famous for norcineria or the noble art of sausage and salami making. Shop fronts are draped with strings of tasty specimens and even family names reflect the ancient trade (such as Ansuini, from ‘swine’). Though a little out of the way for the bulk of the walks, Norcia is handy for Walk 14.

A minor road via Forca d’Ancarano goes to peaceful Preci, on the park’s western edge, where lovely old houses cascade down a steep hillside. With good accommodation and bus links, it is the base for Walk 13. From Preci drivers can loop via canyon-like Nera valley to Visso (see below).

From Castelluccio a road continues northwest to the pass Forca di Gualdo, aka Madonna della Cona, where a detour east terminates at Monte Prata and its hotel, the start of Walk 11. The pass marks an entrance into the inner heart of the Sibillini, a dramatically contrasting world of dense woods of beech, oak and chestnut which provide cover for many animals. Here, deep, plunging valleys are surrounded by bare-topped mountains. The road drops in tight zigzags to the valley floor and Castelsantangelo sul Nera. Quite central to the park area, this charming place has a heritage of monasteries and castles whose fortifications straggle up the mountainside forming an inverted ‘V’. Nera may derive from narici or nostrils, a reference to the two holes in the rock at the base of the spring where the eponymous river rises. Adjacent Valle Infante is fast becoming a favourite haunt for both deer and elusive wolves. Nearby Nocelleto and its guesthouse is the start of Walk 12. A minor road climbs to the modest ski resort of Frontignano. Dominated by Monte Bove it has hotels and Walk 8. The road then descends to Ussita.

From Castelsantangelo, the steep-sided, poplar-lined Valnerina proceeds northwest, alongside the river which feeds a mineral water bottling plant and trout farm. The next landmark is attractive Visso, which has a well-preserved historic centre and is the HQ of the Sibillini National Park. Old castles stand out on the surrounding mountainsides while stern, carved stone gateways open onto the town’s late medieval heart with its lovely Romanesque churches and paved alleys. Set at the confluence of three valleys and consequently three gushing rivers, Visso was repeatedly flooded and in the mid-1800s an expert engineer had to be called in – from Venice, no less. Torrente Ussita, the offending watercourse, now flows obediently through an artificial channel, which makes for a curious sight. Visso is the official start of the GAS trek, and has decent bus services, shops and tourist facilities.

Off to the east in a river valley with dizzy cliffsides stands Ussita, reachable by bus. The road continues up the valley to Casali, a pretty hamlet with accommodation, at the base of Monte Bove Nord and a convenient base for Walk 6. A motorable lane climbs to Forcella del Fargno and Walk 7.

From Visso a busy road climbs north towards Camerino, with branches soon turning off for Fiastra and its lake. This scatter of hamlets, including low-key lakeside tourist facilities, serves as a stopover on the GAS, as well as the start of Walk 2. Walk 1 can be accessed from Monastero, a short drive northeast.

Penetrating the inner Sibillini, a winding road leads southeast to Bolognola with its decent tourist amenities. Its name is believed to derive from Bologna, as it was founded by three exiled families from the north. Another theory claims links with Bona, worshipped by the ancient Sabini people as protector of fertility for land and women alike. Now a small, sleepy settlement, it was once immensely important for the wool trade. Walks 3 and 4 begin in the village itself, while up a dirt road climbing south, at Forcella del Fargno, is the start of Walk 7.

From M Vettore to Pizzo del Diavolo and Lago di Pilato (Walk 17)

Information

In addition to the website for the Parco Nazionale dei Monti Sibillini (www.sibillini.net), Visitors’ Centres (referred to as Case del Parco) operate through the summer months. Information is on offer at park headquarters at Visso ( 073795219), as well as Amandola ( 0736848598), Castelsantangelo sul Nera ( 073798152), Fiastra ( 073752185), Montemonaco ( 0736856462), Norcia ( 0743 817090), Preci ( 0743 937000) and Ussita ( 0737 99190) among others.

Norcia also has a general tourist office ( 0743 828173, www.norcia.net). An excellent resource for the Marche region is English-language website www.le-marche.com, free-phone (from Italy) 800 222111. For Umbria visit www.english.umbria2000.it.

How to Use this Guide

The headings for each walk give:

Walking Time: this does not include pauses for picnics, admiring views, photos and nature stops, so always add on a couple of hours to be realistic.

Difficulty: Grade 1 means a straightforward route on mostly level ground, with no difficulty. Grade 2 is suitable for reasonably fit walkers with minimum mountain experience. (The long-distance GAS is rated Grade 2.) Tackling a Grade 3 route is inadvisable for beginners as it may entail exposed passages and/or orientation problems. That said, everyone should bear in mind that adverse weather such as mist and low visibility, strong wind or rain, can increase difficulty making even a Grade 1 path downright dangerous. Common sense is the best rule.

Above Fonte delle Cacere (GAS, Stage 6)

Ascent/Descent: those accustomed to alpine terrain will appreciate the importance of this figure, especially when it is taken into consideration alongside timing and distance. For instance an ascent of 300m in 1hr is fairly leisurely, whereas 600m in the same time means you can expect to be puffing hard up a pretty steep slope.

Distance: an approximate measure of the walk length.

In the walk descriptions ‘road’ means the way is surfaced and used by cars, while ‘track’ and ‘lane’ are unsurfaced and traffic is limited to farm or forestry vehicles. ‘Path’ always refers to a pedestrians-only route.

Compass bearings are given (N, SW, NNW and so forth), as is right (R) and left (L). Useful landmarks appear in bold type and these are shown on the sketch maps. Their altitude is given in metres (100m=328ft) abbreviated as ‘m’, not to be confused with minutes (min).

Emergencies

If an accident happens or an emergency arises, if possible phone soccorso alpino (mountain rescue) on 118, supplying them with details of your whereabouts and the nature of the problem. Otherwise summon assistance using the internationally recognised signals: the call for help is SIX signals per minute. These can be visual (such as waving a handkerchief or flashing a torch) or audible (whistling or shouting). They are to be repeated after a one-minute pause. The answer is THREE visual or audible signals per minute, to be repeated after a one-minute pause. Anyone who sees or hears such a call for help must contact the nearest rifugio, police station or the like as fast as possible as it may save someone’s life.

‘Help’ is aiuto in Italian (pronounced eye-yoo-toh) and ‘I need help’ is Ho bisogno di aiuto. The general emergency telephone number in Italy is 113, but calls for soccorso alpino (mountain rescue) are best made to 118.

The following arm signals could be useful for communicating with a helicopter:

If you need non-urgent medical assistance ask at your hotel for the guardia medica (24-hour doctor), or go to pronto soccorso (emergency) at the nearest ospedale (hospital).

Insurance is strongly recommended. Those from the EU need a European Health Insurance Card (EHIC), which has replaced the old E111. Holders are entitled to free or subsidised emergency health treatment in Italy. UK residents can apply online at www.dh.gov.uk (‘EHIC and health advice for travellers’ section). Travel insurance to cover a walking holiday is also a good idea as rescue operations incur hefty charges. Members of alpine clubs are usually covered by insurance through their club. British residents can join the UK branch of the Austrian Alpine Club (www.aacuk.org.uk or 01707 386740) or the British Mountaineering Council (www.the-bmc.co.uk or 0870 0104878).

Passo Sasso Borghese, Redentore and Vettore peaks from Monte Porche (Walk 11)

Maps

In combination with a compass, a detailed topographical map showing natural features is essential for exploring the Sibillini on foot. The sketch maps in this guide are only intended as a rough guide and are limited by space restrictions. Hopefully all walks will go well, however in adverse weather conditions such as low cloud with limited visibility, orientation can become a real problem as landmarks are few and far between and a clear map comes into its own.

The best walking map by far is the new 2013 edition of the ‘Parco Nazionale dei Monti Sibillini’ scale 1:25,000, published by SER (Società Editrice Ricerche). It is on sale throughout the park and neighbouring towns, and can also be ordered from www.edizioniser.com. Kompass also do a decent 1:50,000 walking map – map 666 Monti Sibillini – which is available in many overseas outlets. It obviously has less detail, but the smaller size makes it handier to use. Be warned however that Walks 1 and 2 are missing from it, as is a chunk of the GAS Stage 3. The park authorities have also published a new 1:40,000 map (2012), which shows the park routes marked in red and other CAI paths in blue. It is on sale locally but can be downloaded free from the Sibillini Park website at www.sibillini.net.

Users of the GPS will be pleased to know that the waypoints relevant to the long-distance trek GAS described in this guide can also be downloaded from www.sibillini.net.

Waymarking

The long-distance Grande Anello dei Sibillini (GAS) is well marked throughout with red/white paint stripes on prominent rocks and trees, in addition to low wooden poles and clear signposts at most junctions. A ‘G’ is usually included. Recently local authorities and the park have been waymarking routes with red/white paint and placing new signposts at landmark junctions. Note: the park has seen fit to mark its own routes with a red ‘E’ (for ‘escursionismo’, walking) and short identifying number. Several of these routes coincide with the walks described here so extra signs can be expected. There are also short nature trails (N) and MTB (B) routes. Paths in Umbria were recently renumbered – the initial ‘1’ changed to ‘5’.

Waymarking for GAS trek

A warning: don’t be misled by the optimism of the commercial maps which show an extensive network of lovely routes in red flagged with identifying numbers. On the ground very few are so clearly marked and whether or not an actual path exists is another story. Moreover, in the high areas of the Sibillini above the tree line, with no landmarks, this task is more difficult. In any case, where a clear path exists, it’s good practice to follow it and help establish the trail, rather than wandering willy-nilly over grassy slopes and encouraging erosion. Some main routes have red/white identifying marks in accordance with the Italian system of paths of CAI. On the other hand where numbering and markings do exist, this is always explained in the walk description.

Sibillini National Park signposts

What to Take

How do you find that perfect balance between what’s essential, and potentially life-saving, and what only adds unnecessary weight to your rucksack and detracts from enjoyment of your holiday? This is an especially important issue for walkers on the GAS trek. Day walkers have it easier, but should still pack for a range of conditions.

A suggested check list for walking the GAS:

Comfortable rucksack: when packed pop it on the bathroom scales – 8–10kg is a reasonable cut-off point. Plastic bags come in handy for organising the contents.

Sturdy walking boots, preferably not brand new and with a good gripping sole and ankle support. Sandals or lightweight footwear for the evening.

Rain-proof gear, either a full poncho or jacket, over-trousers and rucksack cover. A lightweight folding umbrella is a godsend for walkers who wear glasses on the trail.

Layers of clothing to cope with conditions ranging from biting cold winds through to scorching sun, so T-shirts, short and long trousers, warm fleece and a windproof jacket, as well as a woolly hat and gloves.

Sun hat, sunglasses, chapstick and high-factor sunblock (remember that the sun’s rays become stronger by 10% for every 1000m in ascent). Shade is a rare commodity above the 1500m mark so go prepared.

Personal toiletries.

Emergency food such as muesli bars, biscuits and chocolate.

Walking maps and compass.

Whistle for calling for help.

Torch or headlamp and spare batteries.

An altimeter, handy for understanding weather trends: if the reading at a known altitude (such as a building) begins to rise, a low pressure trough may be approaching, a warning to walkers.

Trekking poles to ease rucksack weight, aid wonky knees and keep sheep dogs at a safe distance.

Sleeping sheet (bag liner) and small towel for stays in rifugi.

First-aid kit.

Lightweight binoculars and camera.

Supply of euros in cash and credit card.

Mobile phone, adaptor and recharger. Don’t let a mobile lull you into a false sense of security in the mountains. Never expect total signal cover; you won’t get it. Don’t take risks thinking that if worst comes to the worst you can call for assistance.

Water bottle – the plastic mineral water containers widely available in Italy are perfect.

Fresh spring water, a boon for thirsty walkers

Note: despite the widespread limestone rock base in the Sibillini, a remarkable number of life-giving springs can be found. Essential to generations of herders for watering their flocks at remote pastures, for walkers the fonti (springs) offer delicious cool refreshment during a hot summer. Springs are marked on maps with a blue water droplet.

However, they can not always be relied upon as prolonged dry weather and channelling for local water supplies have diminished flows. Moral: always carry an abundant supply of drinking water.

Accommodation

There’s a good scattering of reasonably priced family-run hotels, cosy guesthouses and a couple of rifugi walkers’ huts across the Sibillini. In this guide each walk comes complete with contact details of handy places to stay.

The long-distance GAS trek uses mostly rifugi – hostels set in quiet hamlets. Without exception these are excellent structures owned by the park authority – mostly modernised, converted farm buildings which operate by contract from approximately mid-April through to mid-October. They have nice dormitories, hot showers and provide all meals, including packed lunches on request. Bed linen and towels are available for a few extra euros for those who prefer to carry a little less weight. Always phone ahead to reserve your bed, especially early and late in the season as some shut up ahead of schedule. Moreover, at quiet times the kitchen may close for a rest day, though staff will redirect guests to a neighbourhood restaurant.

Other privately-operated rifugi come in handy in the Sibillini – examples are tiny Rifugio Città di Amandola on the eastern slopes, convivial Rifugio degli Alpini at the Forca di Presta road pass, and helpful Rifugio Casali at the base of Monte Bove Nord, without forgetting spartan but strategically located Rifugio Fargno. These too have dorm accommodation, hot showers and meals, unless specified otherwise. Be aware that maps show other huts with the rifugio denomination – such as Rifugio Zilioli on Monte Vettore and Capanna Ghezzi out of Castelluccio. Old herders’ huts, basic and unmanned, they belong to CAI for its members – see Walks 16 and 17 for contact info.

Additionally a number of hotels of varying categories are listed. Many offer a half-board (mezza pensione) option which covers your overnight stay plus a three-course dinner (drinks may not be included) and continental breakfast. Off season it’s worth enquiring about special offers or lower rates, as occupancy out of the July–August period is not exactly sky high.

If your Italian isn’t up to phone calls, once in the Sibillini it’s a good idea to get rifugio or hotel staff to phone to book your accommodation for the days ahead. But do remember to cancel bookings if your plans change! Should the need arise, don’t hesitate to ask to be picked up from – or dropped off at – the nearest town or bus stop. Some establishments will do it as a favour to guests but assume it’s a taxi service and offer payment.

Accommodation on offer

Hotel Felycita at Frontignano (Walk 8)

If you wish to set off early in the morning – usually a good idea in hot weather – settle your bill in the evening, and see if the staff where you are staying are prepared to leave a breakfast tray and thermos out for you.

In general do not assume anyone accepts credit cards and have a supply of euro cash on hand. Main towns including Balzo di Montegallo, Fiastra, Norcia, Visso and Castel-santangelo have ATMs.

If you don’t mind carrying the extra weight, camping out is a wonderful way to explore the Sibillini and gives you the chance to spend more time in the high places. While it is officially forbidden in the realms of the park, it is tolerated for discrete single overnight stays from dusk to dawn. Otherwise base yourself at one of the camping grounds listed here:

Balzo di Montegallo: Camping Vettore, Strada San Nicola 15 0736 807007 open Easter to early Jan www.campingvettore.it

Calcara near Ussita: TGS Amici Colorito 0737 99443, and Estate Inverno 0737 99448.

Castelvecchio near Preci: Campeggio Il Collaccio 0743 939005, open April–Sept www.ilcollaccio.com

Fiastra: Campeggio al Lago 0737 52295

Schianceto above Castelsantangelo sul Nera: Camping Monte Prata 0737 970062, open 15/6–15/9, www.campingmonteprata.it

Shopping for lunch at Visso market

Food and Drink

Pasta is the natural starting point for this important section. Proudly home-made fresh ribbons or luscious thin strips feature high on menus as tagliatelle or tagliolini. Smothering sauces include funghi (local wild mushrooms, unfailingly delicious), ragù, hearty meat sauce, and amatriciana, a spicy stew of pancetta (bacon), tomatoes and onions. Meat is naturally high-profile food in these mountainous areas, notably as a secondo course. Wild boar (cinghiale) may be offered in umido (stewed). Don’t be put off by the offer of castrato which means a type of tender lamb. Delicious when barbecued and sprinkled with herbs and olive oil, it is eaten with the hands. Grigliata mista is mixed grilled meat, generally pollo (chicken), manzo (beef), agnello (lamb) or older pecora (mutton), while rosticini are barbecued skewers of whatever meat is going. Olive ascolane from the Ascoli Piceno district are fat green olives stuffed with sausage meat, crumbed, fried and devoured finger-burning hot!

The Piano Grande di Castelluccio is famous all over Italy for its tiny flavoursome lentils, lenticchie (yes, Italians do get excited about such little things if it’s related to eating). They may be served in a savoury runny soup consumed with toasted unsalted bread or accompanied by spicy sausages. On the vegetable front (contorno, side dish) there is bitter cicoria, wild greens that are boiled lightly then tossed in garlic, chilli and oil. Autumn walkers have a good chance of being fed hot roast or boiled castagne (chestnuts).

Cheese (formaggio) tends to be dominated by pecorino (sheep’s milk cheese) though blends using cow’s milk (latte di mucca) are common. A variant on the delicious soft Italian ricotta cheese is creamy raviggiolo, consumed fresh or used in pasta stuffing as well as desserts. Evidently records survive from the 1500s when it was presented as a prized gift to the Pope.

In the Marche region aniseed (anice) is a common ingredient, and is used effectively with red wine in fragrant, baked biscotti. It is also the main ingredient of Varnelli, a very popular clear spirit, a bit like Pastis. A delicious dessert wine that is home-made and can be exceedingly sweet is vino cotto, with shades of Marsala. Wines vary tremendously though reds tend to dominate. If you’re after booze from the surrounding territory, the Marche has a couple of DOC raters (Dominazione di Origine controllata, an essential guarantee): Rosso Piceno is a very decent table quality, best drunk young, and a white equivalent is Falerio dei Colli Ascolani. Umbrian wines from the vicinity include Colli Martani and Colli Amerini varieties. Naturally, serious wine lists also feature vintages from leading Italian regions such as Tuscany and Piemonte.

Breakfast (prima colazione) is a choice of té (tea), caffé served with latte (milk) or frothed up as a cappuccino, or just short, strong and black (nero) in espresso form. Children can often request cioccolata calda (hot chocolate), but parents should be aware that this rich dense luscious Italian version is highly addictive! Bread, butter and jam (pane, burro, marmellata) complete the picture, maybe a pastry if you’re lucky.

Plant Life

As is immediately obvious, the tree line in the Sibillini is virtually at a clear cut 1500m above sea level. The entire range was once thickly forested with beech and fir, but demands of livestock rearing and nomadic grazers, along with charcoal burners, progressively led to widespread deforestation, resulting in vast expanses of grassland on upper slopes. However, swathes of thick woodland persist at medium altitudes, a stunning spectacle in autumn with infinite shades of red and orange.

The flower arena is vast and extremely exciting for enthusiasts, as a remarkably broad array of blooms flourish thanks to the marvellous diversity of habitats. These embrace a range from low-altitude dry and typically Mediterranean terrains, woodland, pasture slopes, all the way up to alpine-like altitudes well over 2000m. There’s also a decent batch of ‘endemics’ – plants found in a limited geographical area. Most notably, the elevated central ridges of the Sibillini are the perfect haunt for the rare Apennine edelweiss. Like its iconic alpine relative it has creamy-coloured thick velvet petals and pale green leaves. However, this plant grows closer to the ground, presumably to protect itself from the strong winds prevalent here. It begins flowering in late June and is a protected species! Brilliant blue gentians share its habitat along with delicate pink rock jasmine and lilac alpine asters. Not far away on limestone scree are golden poppies and clumps of fleshy-leafed alpine cabbage, yellow and attractive despite the name. A little further down at meadow altitude flourish a wealth of divine orchids, including the exquisite insect types known as Ophrys. Elegant orange lilies and the wine-red martagon variety are never far away. Shady woods on the other hand are the perfect place for batches of deep crimson peonies.

Wild peonies

Trumpet gentians on high slopes

The curious Eryngo bloom

Orange lily

Type of alpine cabbage on scree

The divine bee orchid

Colouring bare fields with pretty splashes of violet-blue along its stem and prickly flower heads, a variety of Eryngo, a curious slender thistle is commonly seen all the way through to the autumn months. It is known romantically in Italian as Cardo di Venere, ‘Venus thistle’. Sun-beaten hillsides at lower altitudes are often colonised by typical Mediterranean vegetation comprising light woods with holm oak and bushes of sweet broom. Masses of aromatic herbs line pathways, their distinctive scent wafting through the air. Mint, oregano and smell-alikes thyme and piquant savory are the most common, along with the distinctive curry plant Helichrysum with woolly yellow blooms.

However in terms of flowers, the most famous spot in the Sibillini and indeed in the whole of Italy, is the Piano Grande di Castelluccio. This huge unique upland basin is an explosion of colour in late spring. Fields where lentil crops have been planted are painted with immense watercolour strokes as wildflowers such as poppies, cornflowers, vetch, mustard and myriad others come out. It is celebrated as the Fiorita and usually happens in early June. (See also Walk 19.)

The interesting Giardino Botanico Appeninico is only a short stroll above Visso (on the GAS trail). Helpful handbooks are Christopher Grey-Wilson and Marjorie Blamey’s Alpine Flowers of Britain and Europe (HarperCollins, 1995) as well as Thomas Schauer and Claus Caspari’s A Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain and Europe (Collins, 1982).

Wildlife

A remarkable variety of wild animals call the Monti Sibillini their home, though most remain elusive to the casual visitor. At best, walkers can expect an interesting range of birds.

The vast expanses of hillsides covered with low grass are the perfect habitat for ground-nesting rock partridge, which take off in small flocks with a cluttering of wings and heart-stopping guttural clucks if surprised. They fly somewhat clumsily for short distances, keeping quite close to the ground. Far above, kestrel and buzzards circle, and four pairs of nesting eagles have been reported. The Piano Grande is excellent for birdwatching.

Apennine chamois with its distinctive long horns

The Apennine chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica ornata), a fleet-footed, nimble mountain goat, is being reintroduced in stages to the Monti Sibillini. A small group inhabits a special enclosure at Bolognola, in semi-captivity but slated for release, while successful re-introductions have been made on Monte Bove. The total population in the Italian Apennines is at 800, so this initiative is being carefully – and optimistically – monitored. They differ from their northern alpine cousin in having much longer horns, but with the same crochet hook. See Walk 4 for details.

Marsican bears, smaller than grizzlies and native to the central Apennines, have been making forays from neighbouring Abruzzo into the heart of the Monti Sibillini of late. The local population of Ursus arctos marsicanus became extinct in the 1800s, but monitoring for droppings and pawprints begun in 2006 has confirmed a fleeting presence. Camera traps are also used, with encouraging results. There is evidence of at least one bear hibernating here. In all, a mere 40 bears survive in Italy’s Apennine parks, under serious threat from man – poison bait is not unknown.

There is also exciting news about wolves in the area. Censuses carried out using the technique of wolf-howling confirm that 20 wolves currently roam the park. Similar to a German shepherd dog, with a reddish-brown coat and grey overtones, Canis lupus talicus is a tad smaller than his North American counterpart; a full-grown male can weigh up to 35kg and a female 25kg. The wolves’ favourite prey are deer, though they do not disdain hares, birds and rodents.

Orsini’s viper, a rare sighting

Roe deer are fairly common in the woods, and a recent project saw the re-introduction of 49 magnificent red deer from Tarvisio in the northern Italian Alps. Concentrated in the thickly forested central valleys of the park near Castelsantangelo sul Nera, several of them wear radio collars to enable zoologists to track them. The Park Visitor Centre there also manages an enclosure for animals in need of temporary assistance.

Shy wild boars feast on nuts and fruit in the beech woods, which also provide good cover. Evidence of their presence comes in the form of excrements, hoofprints and mud baths. Prolific breeders, they have been introduced all the way down the Italian peninsula by hunting enthusiasts though they are protected within the park confines. The newcomers have replaced the native type, smaller in size and less fertile.

A couple of snakes live in the Sibillini, the common viper or adder being the only potentially dangerous one. Light brown-grey with broad stripes or a zigzag pattern on its body, they sometimes hang around abandoned buildings in the hope of rodents for dinner. Sluggish in the morning until solar recharging takes effect (they often sunbathe on paths), they need time to slither away and only attack walkers when they feel threatened. Though painful, their bite is rarely fatal. However it should not be under-rated; speedy medical assistance is imperative. While awaiting help, the victim should be kept calm and still, and the affected limb bandaged to restrict circulation.

On the other hand a rare treat is Orsini’s viper, found solely in the central Apennines. Smaller, with attractive diamond markings, this harmless snake feeds on grasshoppers.

Two tiny crustaceans breed in the rare Sibillini lakes – and nowhere else in the world. The most famous is Chirocephalus marchesonii, a unique freshwater fairy shrimp discovered in 1954 and probably destined to disappear along with its home, Lago di Pilato which is rapidly shrinking (it once dried up completely, in 1990). The creature’s eggs are laid on the water’s edge and can evidently survive a year at a time while the shrimp itself needs to be immersed in water – see Walk 15 for more.

Lastly, be warned that sheep dogs occasionally pose problems. Do remember that they’re just doing their job and see walkers as intruders in their territory. Keep your distance as they have been known to attack outsiders. Under no circumstances bring a dog of your own – even on a leash – as they can disturb the wild animals that rely on these mountains for their home and survival.

Raised river at Visso (GAS, Stage 1)