Читать книгу Alpine Flowers - Gillian Price - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Alpine Moon-daisy thrives in high rocky spots

Wild campanulas and purple gentians, deep gold Arnica blossoms, pink Daphne, and a whole world of other flowers, some quite new to us, here bloom in such abundance that the space of green sward on either side of the carriage-way looks as if bordered by a strip of Persian carpet.

Amelia Edwards Untrodden Peaks and Unfrequented Valleys: A midsummer ramble in the Dolomites (1873)

It happens to all visitors to the European Alps – walkers, climbers and tourists alike. Engaged in a stiff climb, or a leisurely stroll along a mountain lane, and out of the corner of your eye you spot a curious flowering plant. It may even be vaguely reminiscent of something in the garden at home. And you store the image away: ‘Must look that up when I get back’. The idea of this pocket guide is to act as a lightweight companion in the field, with colour-coded pages to make it easy to consult. With no pretence to be encyclopaedic, the guide focuses on the main flowers likely to be encountered and gives readers helpful pointers for distinguishing flowers that appear identical at first glance.

Colourful clumps of blooms make their home on ‘meadows’ of stone

Alpine flowers are unique, hardy species that appear brilliantly yet fleetingly during summer at high altitude. The challenges these tiny plants have to overcome are enormous: extreme temperatures, fierce winds, shortage or excess of moisture, thin soil, threat from livestock and humans and competition for reproduction. They need to do their utmost both to survive and to reproduce, and they have developed remarkably ingenious mechanisms to adapt to the range of stressful factors in their habitats. To say that alpine flowers have perfected survival techniques is an understatement!

Survival Techniques

The formidable mountainous barrier of the Alps begins close to sea level and soars to over 4000m, experiencing dramatic extremes of temperature. Cold is a crucial issue – for every 100m rise in altitude the thermometer drops by about 0.6°C. Moreover, there can be a 20–30°C difference in air temperature between day and night – and that’s only at 2000m.

Challenges notwithstanding, a good 52 alpine flowers are known to survive up to 3500m above sea level, while an amazing 12 species make it to the 4000m mark. The record holder for altitude is the Glacier Crowfoot; an exemplar was reported on the 4274m Finsteraarhorn in the Swiss Bernese Alps. The leaf cells of the highest growing flowering plant in Europe contain a high concentration of sugar which acts as an anti-freeze, lowering the freezing point of its tissues and thus enabling it to live amid snow and ice in sub-zero temperatures. Incredibly, the plant is able to photosynthesise even at -6°C.

Strange as it may seem at first, snow cover is essential to many alpine plants. It acts as a source of moisture and nutrients, but also provides protection from winds and extreme temperatures during the harsh winter months; however, it may mean they are under cover for eight months of the year. The air temperature drops dramatically, especially at night time, and when, for instance, the thermometer plunges to -33°C outside, snug under the snow it may be a comfortable -0.6°C, allowing the plant to function, albeit in a sort of hibernation. The Alpenrose seeks out north-facing slopes where snow accumulates to be sure of long-lasting blanket cover. Such plants can usually survive at temperatures as low as -25°C, which would seem amazing if it were not for the -70°C limit of plants that deliberately grow on windy crests! By contrast, dwellers in nooks and crannies on vertical rock faces, such as Devil’s Claw and Moretti’s Bellflower, cannot count on snow protection, but they are out of the range of chilling winds.

In spring as the white stuff starts to melt, light begins to filter downwards and triggers photosynthesis as the plant wakes up. Here the Alpine Snowbell comes into its own. One of the first blooms to appear in springtime, it can often be seen pushing its way up through the snow; in fact, the heat it releases as it breaks down carbohydrates can actually melt the snow.

The Alpine Snowbell pushes its way up through snow

Unstable terrain, such as the mobile scree slopes or talus found across the Alps, proves another challenge. Fragments of rock falling from higher rock faces and cliffs are constantly adding to the slopes, accumulating on the surface and provoking a downhill slide. A well-anchored root system is essential for any plant to be able to call such terrain its home. Alpine Toadflax and Rhaetian Poppies are experts in this regard.

Survival techniques involving moisture are two-fold: retention and removal. Cactus-like succulents are experts at reducing moisture loss, with their thickly cuticled leaves, and they also have the ability to store water in their stems for times of need. The Cobweb Houseleek is true to its name and has a thick layer of soft netting on its rosettes, which additionally slows moisture loss from the plant’s surface.

Small leaf size can effectively minimise evaporation, and a good example is Moss Campion. The technique used by the Edelweiss is to cover itself with white woolly hairs, which not only reduce moisture loss but also protect the plant from the strong solar radiation encountered at high altitudes. These hairs can also create a micro-climate around the plant where the temperature is slightly higher than that of the surrounding air.

In contrast, Lady’s Mantle practises guttation, a process occurring under conditions of high humidity, particularly at night, whereby the plant exudes surplus water to the rim of its leaves. The drops of water are often mistaken for dew; these drops were treasured by ancient alchemists who claimed they could transform metals into gold – hence the genus name Alchemilla.

In a similar way, Saxifrage plants on limestone rock may find themselves overwhelmed by calcium salts. While the plant uses some for its physiological requirements, it banishes the excess to the edges of its leaves, and the resulting encrustations have the bonus effect of reinforcing the leaf itself.

Calcium salt encrustations on Saxifrage leaves

Keeping a low profile as a protection from the elements is a successfully tried and tested technique used by the likes of Alpine Rock Jasmine, which barely attains a height of 3cm. However, below the ground it develops a root system that serves as an anchor, penetrating all available cracks in the rock. Saxifrages are also renowned specialists in this. With a genus name that means ‘stone-breaker’, the roots do just that, fracturing the rock into particles and delving down, providing stability for the plant while also on a quest for moisture. A number of prostrate woody shrubs such as Retuse-leaved Willow have networks of slender roots and branches that creep over rock surfaces, acting as anchors.

Moss Campion produces a cushion where small creatures can live

Moss Campion grows painstakingly slowly over its 20–30-year lifespan, producing a woolly cushion rich in humus where small creatures can live. Another plant that takes its time is Alpenrose, which needs 8–10 years for its seeds to mature into flowering plants. Then there’s Net-leaved Willow: it has been calculated that a trunk as slender as 7mm could be 40 years old. Nature outclasses the bonsai masters!

Many alpine plants practise solar tracking, which is also known by the rather forbidding term of heliotropism. In addition to placing their leaves perpendicular to the sun’s rays to maximise exposure and encourage photosynthesis, they make constant alterations to the angle of their flower heads so as to receive the full blast of the sun’s warming rays all day long. Buttercups with their yellow saucers are experts in this field; they are able to store heat and the temperature inside the petals can be 8°C hotter than the surrounding air: a great lure for insects that need warm conditions as well as a boost for the plant itself as seed development accelerates. Should the heat become overwhelming, the plant can rotate its ‘satellite dish’ parallel to the incoming rays to reduce exposure; this also minimises moisture loss, essential in dry habitats.

The Carline Thistle, on the other hand, has the advantage of hygrometric (moisture measuring) equipment in the scales that envelop its flowers. This is triggered in adverse weather and the flower closes up in self-defence; it will then open when conditions improve. This behaviour has earned the plant the reputation of being a reliable weather forecaster.

Reproduction

In their very short annual growth period, concentrated into 100 days at most, survival is not the sole life purpose of alpine flowers; reproduction is also crucial. Generally speaking, a plant’s growth period and opportunity to reproduce is shortened by a week for every 100m of altitude. A mind-boggling array of techniques has been invented by flowering plants in order to encourage pollination and spread their seeds, and competition can be fierce.

A Painted Lady butterfly with Round-leaved Pennycress

Attracting insects

Colour is a key factor in attracting insects which, while feeding, inadvertently gather pollen and spread it, thus improving the plant’s chances of reproduction. Many alpine flowers only bloom for the two midsummer months of July and August, and the plants make the most of it with a brilliant display of livery.

Dominant colours at high altitudes are red and purple, but there are lots of blue and yellow flowers and also a multitude of white and green flowers: the pale Edelweiss is a good example.

Bees evidently prefer blooms of pink, blue and yellow and keep a special eye out for flowers with distinctive patterns. They are also suited to flowers with closed or unusual shapes which are fairly sturdy so they can clamber inside.

Cottongrass seeds are attached to a fluffy lightweight head

Insect orchids give pollinators an additional helping hand. The Bee Orchid, for instance, fools bees into thinking they have found a mate, and as they alight the pollen rubs off onto their back to be carried away. The Lady’s Slipper Orchid, on the other hand, entices potential pollinators into its cavity and then makes it hard for them to clamber out again, because of its slippery walls and in-turned lips. In the ensuing struggle they become coated with pollen, which they then carry with them to the next flower.

Flies have weaker vision, reportedly going for bright white and yellow flowers and flatter, saucer-shaped blooms on which they can land without complication. Butterflies, by contrast, have long, thin feeding gear so they prefer tubular flowers. Beetles reportedly like strongly scented flowers as well as bright colours.

Seed dispersal

An important system of seed transport and dispersal – the wind – is exploited by alpine flowers to maximum effect. Cottongrass plants attach their seeds to a fluffy lightweight head that is easily detached and carried off by a breeze.

Other flowers have another card up their sleeve to double their chances of reproducing and seeing another summer. Two notable examples are the Orange Lily and the Alpine Bistort which carry a multitude of ‘bulbils’ or aerial bulbs down their stem; these drop to the ground and mature after two or three years. Similarly, the Cobweb Houseleek has rosettes that can be dropped, propelled by the wind they roll away to a new spot to begin another colony.

Gaining nutrients

Insectivorous plants such as the Butterworts exploit insects in a different way – by eating them! Their sticky leaves act as old-fashioned flypaper, trapping the insects. The victims are digested over two days, supplying the host with essential nitrogen and phosphorous and the remains are left on the leaves to be washed away by rain or dew.

Some plants steal to gain the nutrients they need for survival. The Broomrapes, which do not contain chlorophyll and cannot produce their own food, are parasites that tap into the roots of other plants.

Predators

A particular threat to alpine flora is posed by living creatures. Chamois enjoy nibbling Leopardsbane (known as ‘Chamois Grass’ in German), evidently for its high sugar content, while marmots have a penchant for Forget-me-nots. Some human beings continue the unfortunate practice of picking blooms; it was once the fashion to press them between the pages of a book. Fortunately, most enlightened modern-day visitors take away only photographs. Not only does this preserve the brilliance of the colours, it is also the perfect way to appreciate them. It means, for instance, that the picture can be enlarged, revealing previously invisible aspects of these fascinating and precious plants.

Many of the flowers in this guide are protected – the Edelweiss was the very first, thanks to an 1836 law in Austria. Some, like the Lady’s Slipper, are already rare and risk extinction. It goes without saying that all alpine wild flowers should be left in their natural habitat for others to wonder at.

Migration and Climate Change

The origin of a number of alpine species has been traced to the Arctic region and the freezing steppes of central Asia. With the advance of glaciers during the Ice Ages they migrated southwards, spreading out in search of less demanding conditions, and then staying on after the retreat of the icy masses. Well-known examples are the Edelweiss and the Net-leaved Willow.

Nowadays, with ongoing climate change the Alps, as everywhere, are feeling the effects of the progressive rise in global temperature. Glaciers and snow fields are reducing in surface area, sometimes quite drastically, and the vegetation is shifting upwards in altitude as the plants do their best to seek optimum conditions for growth and survival. The Alpine regions are seeing the arrival of plants previously found lower down on the plains. Monitoring shows that the fastest can ascend 35m in three years. For more see www.gloria.ac.at.

Alpine Squill and White Crocus appear in springtime

Naming

The scientific names for flowers can be quite intimidating, but they are both essential and intriguing in their references. Swedish doctor and naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) introduced the classification system whereby each name consists of two Latin parts, both usually written in italics. The first, beginning with a capital letter, is the Genus (Genera is the plural form), referring to a group of closely related species. This is followed by the actual species name, starting with a small letter, used for members of a group that can inter-breed; this is referred to as the ‘tag’ in the plant descriptions in this guide.

An even larger grouping is the family, a looser grouping of genera that share common features such as flower shape or number of petals that distinguish them from others; examples are the Daisy and Pink families.

Naturally, plants all over the Alps have been given common or ‘vulgar’ names which are much easier for non-experts to remember. As an example, Queen of the Alps is the common name for Eryngium (genus name) alpinum (species or tag). For the purposes of this guide an English name (as well as the Latin name) has been used as the main reference and in the Flower Index, but names in French, German and Italian are also listed for each flower to aid walkers across the whole of the Alps.

These common names often provide a fascinating insight into local beliefs and age-old legends. The example par excellence is again the Edelweiss, German for ‘noble white’ from the story of a maiden who resolved to remain pure, and transmuted into the bloom on death. A second explanation comes from the Italian Dolomites, where they say the flower was tailor-made for a princess pining away for her pale homeland, the moon.

Identification

For the purposes of this book, the altitude of 1500m above sea level has been taken as the cut-off level for alpine flowers, although the odd exception found lower down and considered to be of special interest has been included.

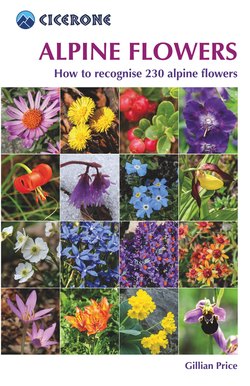

The primary method of identification used here is colour, and to make flower recognition quick and easy – the aim of this guide – flowers have been grouped together under their dominant colour. Naturally, there are infinite variations in shades of colour, especially with blues, reds and purples, so it is always a good idea to leaf through other sections when searching for a flower.

The colours are presented in the following order in this book:

RED: shades from pink to red and burgundy

YELLOW: covering the range through to orange

BLUE: from light hues through to royal blue

PURPLE: delicate lilac to rich purple charged with blue and red

WHITE: predominantly white or creamish. Green has also been included here

and alphabetically by their English name within each colour section.

As well as a photograph, key characteristics of each flower are briefly described in simple language for (and by) the non-expert. Notes on name derivation and traditional uses are included. Specialised terminology has been purposely kept to a minimum; however, some terms are necessary for distinguishing similar species and to help observation and identification. Note Even the leading authoritative reference guides disagree on the identification of some plants so there may well be differences of opinion for the flowers in this guide as well.

Each individual flower heading shows the name in English and then, underneath, in Latin (in italics), then French, German and Italian.

A Glossary and a simplified diagram of a flower are also provided at the front of the book, after the contents page.

Distribution

If not specified in the individual description, the flowers are found widely across the Alps.

There is a marvellous network of botanical gardens across the length and breadth of the Alpine chain, in Austria, France, Italy, Slovenia and Switzerland. Each has expertly labelled species, which is of great help for interested visitors. A list is given in the Appendix.