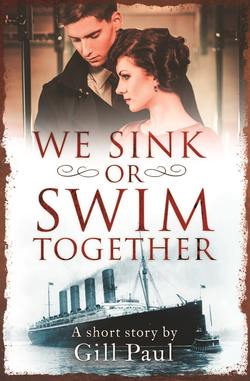

Читать книгу We Sink or Swim Together: An eShort love story - Gill Paul, Gill Paul - Страница 5

We Sink or Swim Together

ОглавлениеGerda stood on deck to watch the view as the Lusitania steamed down the Hudson River, coloured flags streaming from the masts and a choir singing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’. She had lived in Brooklyn for five years but had only travelled into Manhattan a handful of times and had just seen the brand new buildings thrusting up into the clouds – ‘skyscrapers’, they called them – from a distance. She especially loved the Woolworth building, said to be the tallest in the world, its windows glinting in early afternoon sunshine on this fresh spring day. As the ship passed the harbour bar, she could smell the ocean. She knew rivers and sea mingled here because not far up the East River she liked to swim in a floating pool, where the water had a slightly salty flavour.

Gerda had mixed emotions about the trip: she longed to see her sister Thomasine and meet her new niece and nephew, to feel part of a family again, but at the same time she dreaded those familiar questions – ‘Is there not a beau? Someone special perhaps?’ – and the sense of failure they induced. At the age of twenty-nine, she was firmly ‘on the shelf’ and had no idea why it had turned out that way because, she yearned for a husband, someone to love who would stop her feeling so alone. She was pretty enough, with blonde, blue-eyed, Norwegian looks from the country of her birth; she was a talented seamstress who dressed well, given her limited means; and she lived in a respectable house, with no slur on her good name. She met gentlemen from time to time – nice gentlemen, with decent jobs – and they called on her for a while and then stopped, either saying they were ‘too busy’ or simply drifting away without explanation.

‘You’re too direct,’ her friend Charlotte told her. ‘You come across as too keen.’

‘I don’t know what you mean. How do I act differently from anyone else?’ She’d watched other girls, noted their jocular repartee, their bright smiles, the hand placed lightly on a man’s forearm, and she tried her best to emulate them, though it made her feel false.

‘Do you remember when Mr Taylor, the jeweller, began to call on you? You barely knew him and yet you asked about the extent of the accommodation above his shop, as if you were interviewing a potential husband.’

‘I was curious – that’s all.’

‘And with Mr Eliot, a highly eligible bachelor, you asked if he would consider pruning his whiskers …’

Gerda wrinkled her nose; she could see that had perhaps been indelicate, but his facial hair was so overgrown a small rodent could easily have nested therein.

‘You need to stop yourself blurting out personal questions. Be mysterious. Try to act as if you have dozens of gentlemen callers, as if you are the kind of girl who receives proposals every day of the week but will only accept if you meet someone exceptional.’

Gerda mused on this but still couldn’t imagine how she would follow it. If she play-acted too much the man might fall in love with the person she was pretending to be and she’d have to maintain the act throughout her marriage. Perhaps some women did that, but she feared she wasn’t a good enough actress.

Two young boys were running along the deck twirling hoops on sticks, and when she turned to watch, she caught eyes with a dark-haired man standing ten feet away. He wore a trilby and a nice suit: single-breasted, decently tailored, expensive cloth. He smiled and she smiled back instinctively.

A minute later he appeared at her elbow. ‘I didn’t like to disturb you as you seemed lost in thought. I hope you are not melancholy to be leaving New York City.’

He was English, with a northern accent and friendly eyes. ‘Not at all. I was simply admiring the view.’

‘Aha! Do I detect a hint of a Geordie accent?’

‘Actually I’m Norwegian, but my sister and I grew up in South Shields … And you?’

‘Manchester. T’other side of the Pennines. The name’s John Welsh. But friends call me Jack.’

‘Gerda Nielsen.’

He touched his hat. ‘Pleasure to meet you, Miss Nielsen.’

‘What brought you to America, Mr Welsh?’ she asked, wondering if he might be one of those men who came out to the New World to make their fortunes then returned home to collect their wives or fiancées once established.

‘I’ve been in Honolulu working for the Marconi radio company, but I got homesick for the old country. Now I want to go home and settle down, taste Ma’s hotpot and drink a decent cup of tea … What about you?’

‘I’ve been working in a dressmaker’s in Brooklyn but I’m on my way back to visit my sister.’ America was now a hazy mass on the horizon and all around them was dark choppy water with sunspots dancing on the surface. She felt a warmth about this man. He seemed open and genuine, with no edges to speak of.

‘It’s hard being a traveller,’ he said. ‘You make friends in one place, build a life for yourself, but all the while there’s a tug from your roots. I know folks who travel to and fro, year on year, but I don’t want to end up like that. Ma isn’t getting any younger and I should be there to look out for her.’

She smiled. ‘That’s nice.’ It sounded as though there wasn’t a wife involved, but maybe he was just omitting mention of her for now. She wished she could ask but guessed it was the kind of question Charlotte had warned against.

After a while they found some deckchairs and swapped stories. He told her that as a boy he’d liked to discover how things worked; his mother bought him an old alarm clock that he spent hours taking apart and putting together again. After finishing school he studied mechanical engineering at college before getting into telephones and travelling all over America with his work. She told him that her father brought her and her sister to England after their mother’s death then she decided to try her luck in New York after her father died. ‘We were very close,’ she said, her voice catching. She told him of the family friend with whom she lodged in Brooklyn, of her work, of a life that seemed settled yet had an impermanence at its core.

I like this man, she thought. He was easy to talk to. You didn’t have to work to come up with new topics of conversation because he listened to what you said and asked relevant questions and somehow the words just flowed.

The gong rang for lunch, delayed because they’d sailed more than two hours late.

‘Might I have the honour of sitting with you?’ he asked, rising to his feet and offering his arm.

‘I’d like that,’ she said, trying not to let him see the smile that tickled the edges of her lips or sense the leap of her heart.

*

The third-class dining room was grand, with polished-wood panelling, long pine tables and individual chairs for each diner, unlike the benches they’d had on the Mauretania when Gerda sailed out five years earlier. They sat with a family called the Hooks, and a woman called Mrs Williams who was travelling with her six children, and all introduced themselves as waiters brought steaming plates of roast pork with vegetables, rice and bread. The dishes and cutlery bore the Cunard insignia of a crowned lion holding the globe between his paws.

‘Were you nervous about taking this crossing, my dear?’ Mrs Hook asked Gerda. ‘I must say, I would worry if I were travelling alone.’

She was puzzled. ‘I’ve sailed alone before.’

‘I meant because of the German Kaiser’s threat.’ Gerda looked blank. ‘He warned that any ships crossing the Atlantic into the war zone are a fair target for U-boats, whether they are military or not.’

Gerda turned to Jack, her eyes wide. ‘I didn’t know about that.’

He rushed to reassure her: ‘There was a notice in the newspapers a few days ago. It said those who travel in a war zone do so at their own risk, but it’s simply posturing. They wouldn’t dare attack a civilian ship, especially one with Americans on board, because they’d risk dragging America into the war.’

Mrs Hook started listing the famous Americans said to be on board: millionaire Alfred Vanderbilt, the fashion designers Carrie Kennedy and Kathryn Hickson, theatrical impresario Charles Fröhman, all of them in first class.

Gerda was silent and Jack seemed to sense her concern. ‘It will be fine. If there are U-boats in the area, British warships will radio our captain and he will take evasive action. The Lusitania is much faster and nimbler than a hulking great sub. She can make twenty-five knots without straining, while U-boats only do around thirteen. We’re in the fastest ship on the high seas.’

‘That’s why the crossing is only seven days, I imagine. I’ll be glad when we dock in Liverpool, though.’ Gerda shivered.

Jack smiled, looking right into her eyes. ‘If the worst comes to the worst, I’ll look out for you,’ he promised. ‘We can sink or swim together.’

She felt herself fill up with happiness. Did it mean he had taken a fancy to her? Oh, she did hope so.

*

That evening Gerda and Jack strolled on the decks, under an inky black, star-spattered sky.

‘I’ve given so little thought to the war,’ she confessed. ‘My sister writes that all the young men back home are signing up, and women are having to work in the shipyards and coalyards to keep industry going. Yet in Brooklyn, the only concern of the ladies who visit my shop is that they can’t get imported French fashions any more and they want us to make replicas of their favourite Parisian styles.’

‘It’s not just the women who are out of touch. The American lads I worked alongside couldn’t see why Britain went to war just because the Kaiser’s troops marched into Belgium. One asked me’ – he imitated an American accent – “Who even knows where Belgium is?” He laughed, hoarsely. ‘There are many things I like about America, the land of opportunity, but it’s become very insular, despite the people of different races who mix in its cities.’

Gerda didn’t know what ‘insular’ meant, but was too self-conscious to say so. ‘Where I live, they don’t mix so much; they all have their own neighbourhoods. I like listening to Italians on one block then crossing the road and hearing French ladies chattering, or a broad Irishman cursing.’ She blushed. ‘I don’t mean I like cursing – just that it’s colourful.’

Jack laughed. ‘You won’t get that in South Shields, I suppose.’

As they walked, they passed other couples strolling arm in arm and Gerda wished that Jack would slip his arm through hers, but he didn’t seem to think of it.

‘Will you be called up to fight in the trenches?’ she asked, wondering what age he might be. He looked over thirty, but you never could tell.

‘I’m most useful to my country as an engineer. Mr Marconi has arranged a job for me in a lab developing new types of portable field telephones. I start next week.’ He grinned, boyishly. ‘Don’t get me going on the subject or I’ll bore you to tears. I’ve been working on something similar in Hawaii where the technology is leaping ahead. Soon we’ll all be able to make telephone calls to anywhere in the world, whenever we like.’

She watched him as he talked, the words about transmitters and electromagnetics going right over her head. She liked his passion but worried that he was too clever for her. Her conversation about fur trims and tango frocks would never interest him. He’d admired her violet taffeta gown with the spiral-draped skirt, but she hadn’t told him it was based on a Poiret design because somehow she doubted he had heard of Poiret. Perhaps they didn’t have enough in common.

She realised he had paused, waiting for her reaction to something he’d said, something she hadn’t heard.

‘I wish I’d been able to telephone my sister from Brooklyn,’ she said. ‘I’ve missed her while I was away.’

‘You’ll see her very soon, pet,’ Jack said in an exaggerated imitation of a Geordie accent that made her giggle. He was good at accents.

*

Gerda was sharing a four-person berth with just one other passenger, Miss Ellen Matthews, a sour-faced Liverpudlian girl who’d been working in service in Chicago. The cabin was smart, with freshly laundered white sheets and towels bearing the Cunard crest, a washbasin and mirror squeezed between the two sets of bunk beds, and a cupboard with hanging space for gowns, but Ellen wasn’t impressed.

‘I’m sure I’m not going to sleep a wink on these beds. They’re narrow and hard as ironing boards’ … ‘Why was there no fish course at dinner? I’m used to better’ … ‘I asked a steward to fetch me a cup of tea and he said I’d have to fetch it myself from the ladies’ waiting room. Have you ever heard the like?’

Gerda unpacked a few essentials and changed into a nightgown, slipping it over her head and unfastening the hooks of her brassiere, corset and suspenders beneath its tent-like cover. She cleaned her teeth with cherry tooth powder then unfurled her hair and brushed it out before pinning the curls in place to set them overnight.

‘Is that your sweetheart, the man I saw you with tonight? Are you two engaged?’ Ellen asked.

‘He’s a friend,’ Gerda replied, suddenly unwilling to admit she’d known him for only a few hours.

‘You want to watch it.’ Ellen narrowed her eyes. ‘Folks are already talking about how much time you’re spending together, like a pair of lovebirds. You don’t want to get a bad name.’

Gerda was annoyed. ‘It sounds as though you’re jealous,’ she said, making Ellen huff indignantly and clatter her bedpan, muttering under her breath about decency and respectability.

Gerda clambered into bed, pulling the sheet up to her chin. Her toes pressed against the wooden board at the end; at five foot six inches she was taller than average. Jack was a couple of inches taller than her and she worried he wouldn’t sleep well in such short bunks. She closed her eyes and waited for Ellen to finish her preparations and turn out the light before she let her thoughts wander freely.

Jack still hadn’t said if there was a girl waiting for him back home, but surely if there was he wouldn’t be spending so much time with her? It wasn’t fair to give someone the wrong idea. She knew what that was like from bitter experience. But he seemed nicer than Alan Slaven … much nicer.

Everyone had assumed she and Alan were engaged. They met when she was eighteen and stepped out together for the best part of two years, going for long coastal walks or visiting tearooms on his days off. She assumed they’d be wed after he finished his apprenticeship as a butcher, but in fact the long-awaited proposal never came. When rumours reached Gerda that he’d been seen dancing with another woman – a very pretty woman, according to her informant – she was simply surprised. It seemed incongruous. Alan had never struck her as a ladies’ man, with his ruddy face, thinning hair and big-knuckled hands. He’d seemed like a safe bet.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said when she raised the subject. ‘I’m very fond of you, Gerda; you’re a nice girl, but I don’t love you the way you should love someone you’re planning to spend the rest of your life with.’

‘What on earth does that mean? You’re just looking for pastures new. You’re a charlatan.’ The anger erupted out of her and she kept berating him until he picked up his hat, apologised one last time and disappeared.

‘What will folk say?’ Thomasine worried. ‘You’re tainted goods; all the time you’ve spent together without a chaperone and now he’s gone and taken up with someone else. He’s ruined you.’

Wherever Gerda went, she saw people gazing at her with undisguised sympathy, or whispering behind their hands. It will pass, she thought; but six months later when Alan married the ‘other woman’, the gossip started again and this time she’d had enough. To be thrown over by any man was bad enough, but to be thrown over by someone as unappealing as Alan Slaven had spoiled her chance of finding a decent husband in South Shields. She thought of going to America then but her father got ill and she couldn’t bear to leave and miss the time he had left. It was only after he died, when she was twenty-four, that she travelled to New York to lodge with her mother’s old friend Else Gabrielson. It was to be a fresh start in a country where no one knew her, a place where she could find a husband who didn’t know she was so-called ‘tainted goods’. Perhaps she had left it too late because, five years on, on the 1st of May 1915, here she was on the Lusitania, heading home again without a man. The neighbours would look at her ringless hand and sigh. Unless …

How could she tell if Jack Welsh was sincere? He seemed to enjoy spending time with her and they conversed easily, but what if it was simply a shipboard dalliance for him, a way of making the voyage pass more quickly? How could she ever be sure? And then she remembered him saying they would sink or swim together and thought what a chivalrous thing that was to say. She hoped to goodness he had meant it.

*

Next morning, Jack was waiting when Gerda entered the dining room for breakfast and he came to sit by her, enquiring how she had slept and asking if her cabin was comfortable. She found herself telling him what her cabin-mate Ellen had said about folks calling them lovebirds, and was interested to find it did not bother him in the slightest.

He chortled: ‘So we are to be the on-board entertainment, are we? We should put on a good show in that case.’ With a wink, he reached over to squeeze her gloved hand.

Gerda giggled and turned her face away so he couldn’t see she was blushing.

‘I like that smile,’ he said. ‘Your secret smile.’

After breakfast, there was a church service conducted by Captain Turner in the second-class lounge, which had mahogany tables, armchairs and settees on a plush rose carpet, and long windows looking out to sea. Jack sang the hymns enthusiastically, if a little off-key. Gerda mouthed the words from the sheet, unfamiliar with the Anglican service, and glanced round at the smart outfits of the first- and second-class women: she spotted the designer Carrie Kennedy wearing a fur-trimmed red velvet suit, and her sister Kathryn Hickson in an elegant grey suit with seven-eighths jacket. Afterwards, she and Jack wandered out on deck and stood at the rail, gazing across the vastness of the ocean.