Читать книгу Stolen Pleasures - Gina Berriault - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

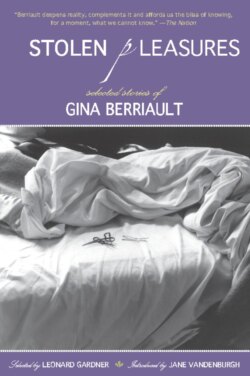

ОглавлениеIntroduction

By Jane Vandenburgh

GINA BERRIAULT CAME into life and her own very acute state of sensitivity and awareness during the late 1920s in one of our dimmer coastal towns—Long Beach was then so parochial it was known as “Iowa-by-the-Sea.”

Richard Yates, in his tribute to Berriault’s work, calls her California “that warm and dismaying place.” Here she is, in the title story from this volume, describing a street in just such a town:

Every house had a palm tree and a lawn, and some had a piano inside, a dark, sternly upright object in its own realm called the living room. Delia and her family had no piano and therefore no living room. (p. 139)

The story is set during The Great Depression, as the world hovers anxiously on the brink of war. Childhood, in these stories, is filled with foreboding, tragedy all but foretold: this girl’s father will die, her mother will go blind, as did Gina’s own.

The ordinary lives you’ll read of in this collection play out always against just such a vast scrim of darkness and risk, which resonates profoundly—given economic and environmental uncertainties—with our own sense of apprehension and unease.

We meet Berriault’s characters in astonishing intimacy, as they come to existential realizations: life is short, love is brief, beauty fragile, all sense of order imperiled. It is only the realm of Art—symbolized by the music Delia’s family cannot afford—that can save us. It’s in the coherence offered by great painting and music and writing that we all may find a sense of larger meaning, were we granted access.

That we feel oddly conforted by the dark beauty of these stories is simply another of Gina Berriault’s many astonishing gifts. So powerful is her empathy for each of her sharply envisioned characters—she calls them “those with wounded hearts”—that we, knowing we’re wounded too, feel more than seen by her, we feel acknowledged.

We are no less lonely than we were, but we’ve been reminded we are not alone in our loneliness.

I KNEW GINA only during the last decade of her life and understood her to be a deeply private person, exquisitely watchful, shy to the point of reticence. If she seemed not exactly of our times, it’s probably symptomatic of her genius. She utterly lacked all will toward personal divulgence and was never cursed by the self-congratulatory or confessional impulses that so plague our own age.

And while she was as economical in her prose as any writer I know, she did not participate in that plain-faced, stripped-of-affect fiction that followed Raymond Carver down the trail first hacked by Hemingway, as each took his machete to all that sounded to them like false and romantic gush. All three were masters at getting the sound of the American language down precisely. Though she carefully guarded her privacy, the writer can be glimpsed in the character of Delia, who inhabits two of the stories here. This girl becomes a woman who still imagines herself standing outside the room in which the music was being played:

. . . if you were a man interested enough to take her out on a date and talk to her about a famous pianist or sax player or a concert you’d been to you’d wonder why she couldn’t look you in the eyes…why she got clumsy, knocking a fork to the floor or tipping over her wineglass. (p. 140)

One of three children of Jewish immigrants—Gina’s mother was born in Latvia, her father in Lithuania—she understood all too well the personal side of the larger story, that of global dislocation on a mass scale caused by economic and political turmoil.

Her family owned their own home until her father’s death during the Depression. As a young woman alone in San Francisco, struggling to write and to educate herself, she knew it was in Art that she found true sustanence.

Delia imagines that culture allows us to “. . . fill the emptiness of our life with marvelous things that were out there for everyone to share . . .” She takes her sister, who is visiting, to an art museum:

. . . there was always one woman in the museum throngs or a child who kept glancing at Fleur to figure her out: her refugee look, her sacrificial look, her look of displacement. No one could ever hope to know where Fleur came from (p.152).

The sisters later talk to one another in the dark from their twin beds in Delia’s rented room, each knowing pieces of their hidden past, each understanding how spiritual and material depletion can rebound through generations. Their father, suffering a heart attack, was taken off to a charity hospital, Fleur says, where he was denied a sip of water and died alone.

It was when Gina’s own father died that she went to work, writing for a gem merchants’ trade magazine to support the family. She used her father’s manual typewriter, stepping up into his job. She called her father “the mentor for her spirit.”

Hardworking, always painstaking and diligent, she not only produced this work-for-hire, but later on novels, stories, screenplays, and at the end an illustrated book for children.

She achieved what she did, became the writer she was, by virtue of sheer talent and intelligence, and by her tireless devotion.

IN THESE, THE best of her stories, we can see the effect of all that labor. Gina Berriault, famous for writing and rewriting, for never being satisfied, for pushing herself always onward toward the perfect story, the one that seemed to pre-exist already, as if precisely known to itself. She worked until she felt each story achieved its own integrity.

Gina Berriault won two Commonwealth Club Medals for fiction. In 1996, her collected stories, Women in Their Beds, won both the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Pen/Faulkner Prize. In 1997, she was given the Rea Award for lifetime achievement in fiction written in the shorter form. This most important of prizes has, over its now twenty-year history, rewarded the best story writers working in the American idiom, including Grace Paley, Cynthis Ozick, Tobias Wolff, John Updike, Paul Bowles, and Alice Munro.

We cannot really know where a talent like this comes from. We do know this: Gina Berriault was an avid student of the Russians. One of the two Delia stories collected here is dedicated to “My true friend, Isaac Babel, in his basement.”

And the final story in this collection is called “The Overcoat.” It opens with a young man, destroyed by addiction, on a bus on his way north to find the parents from whom he’s been long estranged. He travels for days wearing an overcoat so massive it all but outweighs him. In reading this story we may be haunted by the feeling that we’ve seen this coat before, and have felt its weight on us, that it serves as transformational artifact. Indeed, it becomes, in the story, less an article of clothing and more the husk this man will leave when he has finished dying.

And we remember Dostoyevsky’s declaring: “We all come out of Gogol’s ‘Overcoat.’” In the master’s great short story we can witness the birth of modern Russian realism. But it’s to Chekhov we look to see where this most original of our story writers fits. Though Gina Berriault spent nearly her entire life living and working in California, she is no more a regionalist than was the doctor in writing from Yalta.

She was a writer so dedicated to the modernist realistic tradition that she sets each story into a context that is grander, deeper, always recognizable and always meaningful: it is this city that holds the apartment house where the two sisters talk across this particular darkened room. The sense of importance given to an almost whispered narrative context is another reason these stories read less like a slice of life and more like novels in miniature.

Each story feels full, saturated with its own past, all those moments colliding to add up to exactly this one. Everything is vividly seen and accurately heard. Berriault’s knowledge of each of her characters is so direct and sure we can chart their entire lives from our witness of these highly charged and particularized moments.

Ocean liners sailed right on through the Depression years, and certain person who had jobs, like teachers, could go and visit countries that were not at war. Miss Furguson had been to Japan (p. 117).

Throughout her work we witness how global concerns play out in the lives of her characters on the most intimate of levels. This is a writer who understood that events of our shared history are not to be ignored. She did not share the impulse of those with that blonde, bland American feeling of post-war indifference, nor the will toward otherworldly escapism that subtly told us we somehow stood apart, that we had, in fact, transcended history.

She knew that the same large and hard-to-understand events that displaced her parents were directly linked to other sources of darkness and calamity to which the twentieth century was witness. She understood that those same inchoate forces sent a cadre of secret police to arrest Issac Babel, taken from his basement in 1939 and never seen again. When his widow was asked if Babel had been executed by Stalin for political reasons or because he was a Jew, Pirozhkova answered: “It was done because he was excellent.” “The Tea Ceremony”—the story Gina Berriault dedicated to Babel—is one of the last works of fiction she completed before her death on July 15, 1999.