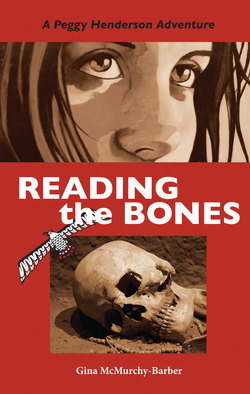

Читать книгу Reading the Bones - Gina McMurchy-Barber - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 3

ОглавлениеThe next morning Eddy and I stood at the edge of the hole, looking down on the burial. She had already cleared away some of the dirt, and I could see a form beginning to emerge. It seemed more like a small child lying on its side, curled up in sleep. I felt a little weird staring at those fragile bones, bare of all life.

“Okay, Peggy, when excavating a site, what’s more important at the time — the artifacts you find or the place you find them?”

In some ways Eddy reminded me of Mrs. Hobbs, though not in the way she dressed. Eddy wore a goofy hat covered in souvenir pins from all over the world and a khaki shirt with little pockets holding lots of little things, like a plumb bob, a measuring tape, and calipers. Her hands were thick and tough — the kind used to hard work and getting dirty. But she was easy to talk to like Mrs. Hobbs and made me feel as if what I thought mattered.

I searched for the words Eddy had used the day before. “It’s the artifacts in ... ah ... situ — that’s it! The artifacts in situ can tell you the most. That’s why an archaeologist never takes the stuff out until every bit of information around the artifact has been recorded.”

Eddy smiled. “What kind of information are we looking for?”

“Okay, I know this. How deep the things are from the surface ... ah, what other stuff is associated nearby ... um, and what the layers of soil are like. That’s the matrix, right?”

“All right! You’ve been listening! Now that you’ve passed the test you’re ready to be my assistant.” Eddy’s round, wrinkled face smiled approvingly. Gently, she stepped over the string barrier she’d made and knelt by the bones. “Hand me the trowel and dustpan. I’m going to start by levelling this layer that you and your uncle started. Before we can remove the skull and bones, we have to see what else this burial can tell us.”

I handed her the tool box. Many of the objects inside were things most people had in their garden shed — a dustpan, a bucket, a hand broom, and a diamond-shaped mason’s trowel. There were also some plastic sandwich bags, a small paint brush, and a dental pick like the one Dr. Forsythe used.

Carefully, Eddy scraped the dirt into the dustpan “We’re not planting flowers and shrubs, so it’s important to consider that just millimetres below, or in the next scoop of matrix, we might find some important bit of information. We don’t want anything to be damaged or missed.” Eddy’s pudgy body was perched over the burial as if she were a medic giving first aid. Occasionally, she stopped and wiped her forehead with the red bandana hanging loosely around her neck.

Soon the bucket was filled with black sandy soil dotted with bits of broken shell. “Okay, let’s screen this stuff.” She pointed to a rectangular frame covered in fine wire mesh dangling from three poles tied at the top like a teepee. “Once we’ve screened away the loose dirt, we’ll look carefully for any small things I might have missed.”

I struggled to carry the bucket over to the screening station. Every time I hoisted the pail up to dump its contents, the screen swung away. After three tries, I finally managed to empty the pail.

“We need to look for anything that appears to be plant life, small animal bones, or shell fragments that I can use to determine food sources available at the time of this burial,” Eddy said. “There might even be some small artifacts, like flaked stone from tool-making.”

I pushed around the cold, damp soil, which felt like coarse sandpaper to my hands.

“That-a-girl!” Eddy said. “Now push it around evenly and search for anything that might be important.”

I studied the surface without recognizing anything special.

“Okay, nothing there,” Eddy instructed. “Now start to shake it back and forth.”

I rocked the screen as if it were a baby in a cradle. “You’ll have to do better than that,” she told me. “Give it a good shake.”

The tiniest grains of soil fell through, covering the plastic sheet with an ever-rising mound of dirt. I could imagine what Aunt Margaret was going to think when she saw all this dirt flattening her grass. Soon there was nothing left in the screen except some tiny pebbles and bits of broken shell that were too large to slip through the wire.

“It’s nothing too exciting, but we’ll bag these shell fragments as a food sample.” Eddy brought out a clipboard, a paper form, and a plastic Ziploc bag. At the top of the paper were the words “Artifact Record Form.” Below was the word Site, and next to it Eddy wrote “DhRr 1 — Peggy’s Pond.”

“These letters are a code that will tell any other scientist exactly which site this sample was taken from.” Eddy winked. “Kind of like when X marks the spot on a pirate’s treasure map.”

“But why did you write Peggy’s Pond?”

“It’s customary to name a site. Sometimes we name it after the local Native group, or the landowner — or in this case the site discoverer.”

My cheeks turned warm with colour, then I watched as Eddy wrote: “Shell samples are a possible food source, found in level 1, ten centimetres below datum.” After that she filled the bag.

“Seems kind of gross that broken shell bits could be evidence of what ancient people ate, especially with a dead person in the mix,” I said. “That’s about as appetizing as finding the remains of a dead pet in the garden along with the zucchini and carrots.”

Eddy chuckled. “I can see what you mean. But all these broken shells are here because the ancient ones heaped up the used clamshells or fish bones when they were finished with them — kind of like an ancient garbage dump, except it was all organic. Archaeologists call this a shell midden. We’re not absolutely certain why, but it’s quite common in this area to find burials in the midden.”

“I bet it has something to do with covering the scent of the body so wild animals don’t go digging it up. Nothing could stink as much as rotting fish guts and stuff, right?”

“That could be it,” Eddy said, smiling. “All right, now that you’ve seen how we record information and store it in bags, you can do the next one.”

She picked up the bucket and returned to the excavation pit. I knelt beside her on the grass, staring at the black midden like a pup ready to pounce on a ball.

The morning passed quickly, and I lost track of the number of buckets I screened. We didn’t find a single artifact, and all there was to show for our hard work was a neat mound of loose sand, shell, and dirt under the screen.

“My legs are getting stiff,” Eddy finally said. “How would you like to dig for a while?”

My heart leaped the way it had when Uncle Stuart said I could back the car down the driveway. Careful not to crush any fragile bones, I stepped inside the small pit. Moving around was a bit like trying to navigate inside a cardboard box.

“Remember,” Eddy warned, “these bones and artifacts have been buried here for thousands of years, so go slowly and be gentle.”

Okay, now that actually made me nervous.

I knelt and brushed away a thin layer of dirt dried by the sun. The bones were yellowy-brown, and I could see that some of them were badly cracked and crumbly.

“You’re doing fine. And remember that an archaeologist needs to be patient.” Eddy bent down and pointed to a spot near the top of the skull. “You see this here? I’m pretty sure it’s some kind of a stone tool. It might even be a woodworking tool.”

I could almost feel the pulse in my fingertips and had to resist the temptation to rip the stone out. My hand trembled as I scrapped around the artifact, then scooped and dumped the black earth into the bucket.

“Aha! You see, you see!” Eddy was crouched over the hole with her nose practically in the dirt. “It is a burin! Good job, Peggy!”

The object looked like any run-of-the-mill rock to me, except for the fluted edges that came to a point. “What’s it for?” I asked.

“It’s a tool we think was used for carving or engraving. You know what this means, don’t you?”

I stared blankly.

“This is the first bit of cultural material that tells me this individual was quite likely a craftsman or a woodworker.”

I was a bit confused. “That seems like a waste. It’d be like us burying a perfectly good skill saw with some guy just because he was a carpenter.”

“You’ve got to remember, Peggy, that early people had a belief in an afterlife — much like people today. But in their case they wanted to make sure their friend or loved one had everything he or she needed for the next world, like tools, food, even jewellery. We call these grave goods.”

“It sure would be nice if Peggy was as interested in keeping the floor of her bedroom as clean as this hole.”

I quickly turned to see Aunt Margaret standing behind us. I had no idea how long she’d been there listening.

“Peggy, maybe Dr. McKay will let you borrow her broom and dustpan later. You never know what neat artifacts you’ll find under all that dirty laundry.” Even though she was smiling, I could detect a prickle of annoyance in her voice. “And before you come into the kitchen, make sure you scrub your hands with soap and water.”

“I can assure you, Mrs. Randall, this is the cleanest dirt you’ll ever find. And if Peggy keeps up the way she’s been going, we may have ourselves a future archaeologist.” Eddy gave me a thumbs-up.

“To be honest, I think she’d do better pursuing something else,” Aunt Margaret said. “I don’t imagine there’s a big demand for archaeologists. By the way, I hope having her help you isn’t slowing things down. Because I don’t mind telling you that I can barely sleep at night knowing this ... this ... thing is out here.”

Her nose wrinkled and her top lip curled as she wagged her finger at the bones in the ground. I wondered if Eddy had noticed how red my face had turned.

Eddy smiled at my aunt. “Well, that’s just because you don’t know him. Why don’t I tell you a bit about our friend here?” Aunt Margaret’s pinched face didn’t relax, and Eddy must have sensed she had a lot of convincing to do. She bent over and gently picked up some of the bone fragments.

“You see, an archaeologist reads bones like someone else might read the pages of a book. They tell us quite general things about the individual, like gender and height. But often there are other details etched into the bones like a primitive code that can tell us more intimate things — perhaps about a person’s childhood, whether he had enough to eat, or what caused his death. It’s a bit like being a detective who finds it’s the tiniest details that can tell the most.”

Some of the bones Eddy held were the size of a Tootsie Roll. But one was a sickly boomerang shape. “You see here? These phalanges or finger bones show a terrible case of arthritis. It must have made doing handiwork difficult. And the vertebrae in this spine are fused into a single carious bone, so it must have been pretty tough walking with a crooked old back like this.” Eddy smiled at me and placed the curved spine in my hand. It was so fragile that dry fragments fell off and settled in the crease of my hand like crumbs of toast.

“We know that everyone was needed to contribute to the survival of the whole village, and for this poor soul, carving or basketry would have been difficult. But this burin here tells us that somehow he did it. The arthritis also strongly suggests this was an individual who lived a long life. Maybe he was an elder, a keeper of clan stories, perhaps a grandparent like me. And while he struggled to do his share of the work, all along he was probably in pain.”

As the gnarled backbone rested in my hand, images flashed through my mind of an elderly man struggling along the sandy shores or down rooted forest trails.

“I know there are many differences between us and these ancient people,” Eddy continued, “but I’m pretty sure we have a lot in common, too. They must have laughed at silly things, cried when someone they loved died, squabbled occasionally. But even during the tough times, every member of the village had an important job to perform, whether it was bringing in the fish, making baskets, or preserving food for the winter. So there wasn’t much time for feeling sorry for yourself.” Eddy took the fragile bones and put them back in the pit ever so gently as though trying not to cause them any further suffering. “And like everyone else, this poor dear had his place in the clan and his job to do.”

“Hmm, that’s very interesting, Dr. McKay,” Aunt Margaret said without a hint of sympathy. “But it doesn’tchange the way I feel. I’ll sleep better at night when it’s out of my yard.”

Blink! Her words had the same effect as a sudden power failure.

That evening I tried to call Mom on the phone to tell her about the excavation. I was desperate to talk to someone who cared about what I was learning. But her voice sounded tired, and she asked me to call back the next day. It wasn’t like her to hang up without some kind of encouraging word.

After that I hid in my room. I wasn’t in the mood to listen to Aunt Margaret complain about the mess in the yard, so I decided to organize my shell collection. At first I arranged them on my bed from largest to smallest, then reordered them into shell families. When that didn’t seem right, I placed them in groups according to shapes. The tusk shells were the only long, thin shells in my collection. As I held them in my hand, I was reminded of the burial in the backyard. Eddy had talked about those old fragmented bones as if the man they had belonged to was someone deserving of respect. Then I recalled the stone tool. Eddy had called it a burin and had said it was used for carving. To her it was another clue, something to help her understand a prehistoric old man whose hands didn’t work the way they used to.

I sat on the edge of the bed and closed my eyes. There, in the darkness of my mind, I began to see him. He had long grey hair that cascaded past his shoulders and down his bent old spine.

Far beyond the village the sun rests for a few moments on the mountaintops just before it slips behind them and into the sea. The people are getting ready for sleep inside the dark clan house. Many small pit fires burn low, and embers give off warmth and light. Some of the elders are already asleep on their cedar-bough beds. A few of the women rock and feed babies, while their men talk in hushed voices, clouds of smoke rising from their pipes.

The old man lies as comfortably as possible, propped slightly upon the bearskin rug at one end of the clan house. The children around him sit motionless, attention fixed the way the white-headed eagle watches for dinner.

“So Dark Sky wandered far and wide each night, searching for his courage.” Shuksi’em speaks slowly, his deep voice rising and falling ever so slightly like the gentlest waves on a beach. “And every morning he returned to his village disappointed that he had failed to find it. We know he still searches to this day because every morning we wake to find the grass drenched in his tears.”

The children gaze at Shuksi’em’s wise old face ... knowing ... waiting ... for the story’s life lesson. They have heard it many times already in their young lives, but each time is like the first, and they wait to gobble every word like baby birds swallowing worms from their mother’s beak.

“It took great courage for the boy to wander alone in the woods each night, yet he thought he had failed in his mission. Someday you, too, will wander alone, struggling in the darkness, searching for the strength to face life’s challenges. And when you do, remember to have faith in yourself. The courage you need is within you, waiting to guide you into the light.”

Shuksi’em smiles, his eyes dancing with firelight. Slowly, he turns away to flatten his bed and lays his head down for sleep. One by one the children quietly creep off to their own beds somewhere close to a mother or father.

Feeling joy bubble up inside him, Shuksi’em smiles again. He enjoys his time with the children. They are filled with the promises of new life and none of the sorrows. Suddenly, a large, warm body pushes against his bent spine. It is a familiar shape that wraps around him like a shell to its clam.

“It seems like your stories grow longer every time you tell them, old man,” Talusip says to her husband. “You should not forget that some of us need our sleep more than you.”

“I, too, would like more sleep, but the damp mist of the night sneaks into my back and hands leaving me stiff with pain” Then Shuksi’em feels his wife’s strong fingers gently pound and rub his crooked old spine until he finally drifts into a dream.

In the dream Shuksi’em returns from sea after many days. He is tired and ashamed that he has no catch of fish for his hungry clan. As he rounds the small finger of land only a short distance from his home, he suddenly thinks he has come to the wrong place — for the land is bare. He searches for a familiar sign, but even the clan house is gone. His heart thumps harder, faster. He is so weak now that he can hardly paddle his canoe. With no fish in the ocean to eat and no forest to provide food and shelter, how will his people survive? As Shuksi’em pulls his boat onto the shore, he feels himself dissolve into the sand.

When Shuksi’em awakes, the frightening images are still in his mind. But around him are the gentle sounds of the sleeping clan. And Talusip’s body heat still seeps into his own. He is relieved that all is as it should be. As his fear slips away, his heart begins to settle and the rhythms of the night lull him back to sleep.