Читать книгу Broken Bones - Gina McMurchy-Barber - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter One

I was barely alive that morning when I stumbled into the kitchen and poured myself a bowl of Corn Crunch. I’d watched videos until 2:00 a.m., so my plan was to slurp my cereal quietly with my eyes nearly shut and then shuffle back to bed and sleep another two hours. It was the first long weekend since summer vacation ended, and I looked forward to having nothing to do — no rushing around, no school, no homework, no early to bed, just the bliss of nothing. But all my sleepy bliss was suddenly shattered when Uncle Stuart burst into the kitchen.

“Peggy, take a look at this — just came in the mail.” Uncle Stuart shoved a newspaper clipping in my face and held it there until I sat up. My eyes were still blurry, and I had to squint to read the heading: GOLDEN’S GRAVEYARD AND HISTORICAL SITES VANADALIZED. “Take a look at the byline.” I peered closely. It read: “By Norma Johnson.”

“Norma Johnson?” I said sleepily. “That’s Aunt Norma.”

“Ding, ding, ding — give that girl a prize,” Uncle Stuart said. “She’s a genius.”

I flicked a spoonful of milk and cereal at him. Just as it landed on the floor, Aunt Margaret walked in from the backyard carrying a box full of spotted and bumpy Golden Delicious apples.

“Oops. Hi, Aunt Margaret.” I winced like a little kid who’d just been caught with a hand in the cookie jar.

“Hmm, and who’s going to clean that up?” My aunt wore one of her I-don’t-get-this-kid expressions. At that moment Duff padded into the room and quickly licked up the spot of milk. He tentatively nibbled at the cereal, then spat it out on the floor as though the sugar-coated, lightly toasted, bleached white flour wasn’t absolutely delicious.

“Look! Did you just see what your cat did, Aunt Margaret. That’s disgusting. I shouldn’t have to clean that up.”

Aunt Margaret only sneered. “Okay, that’s enough. It’s much too early for this nonsense.”

It was always too early or too late or too something for Aunt Margaret to get a joke.

“Aunt Norma sent us one of her stories from the newspaper and this letter,” I said, quickly redirecting her attention. I was getting good at that — one of my many tricks for survival when living with Aunt Margaret.

“Oh, let’s see, Stuart,” Aunt Margaret chirped as she snatched the letter and clipping out of my uncle’s hand.

“VANDALS DISTURB BURIAL IN PIONEER CEMETERY by Norma Johnson. Have you two already read this?”

“No, Uncle Stuart was bugging me. That’s why I had to flick cereal at him to make him stop. What’s it about?” I glanced at Uncle Stuart, who silently whispered, I’ll get you for that.

“It seems someone has been vandalizing historical sites around town, and the latest disturbance was to one of the graves at some long-forgotten Pioneer Cemetery. Police are narrowing down the suspects and think it’s some teenager. He could face heavy charges and up to ten thousand dollars in fines.” She put the clipping on the table and started to read the letter.

My mind flashed to the burial I accidently disturbed in the backyard last summer when Uncle Stuart and I were putting in the fish pond. We were new to Crescent Beach and didn’t know it was once a prehistoric First Nations fishing village.

As it turned out, finding that burial was the best thing that ever happened to me. I learned a lot about bones and how to excavate an archaeological site from Eddy, aka Dr. Edwina McKay. Even though Eddy was sort of old, a grandmother, in fact, she really knew how to relate to kids. She taught me that if you knew how to read the bones, they could tell you a lot about the past and of the people who once lived. It turned out that the guy buried in our backyard was a three-thousand-year-old carver. The most interesting artifact we found was a small carved pendant.

“What about the grave?” I asked. “Does it say what’s going to happen to it?”

Aunt Margaret didn’t seem to hear me and just continued to read Aunt Norma’s letter aloud. “Norma says: ‘The Golden Pioneer Cemetery was long forgotten by most of the residents until the 1980s. That’s when some old guy dug up a skull and tried to trade it for a beer.’” She put down the letter in disgust. “Honestly, some people are beyond decency!”

“Go on,” I urged. “What else does Aunt Norma say?”

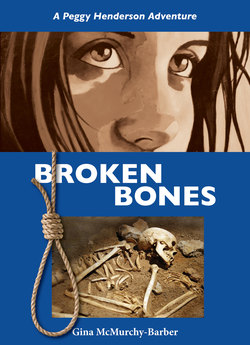

“Apparently, after the human remains were disturbed, archaeologists were called in and excavated a large part of the abandoned cemetery. Soon after, the place was again forgotten — that is until just last week. Somehow the police were alerted that another pioneer burial had been disturbed. Norma says some citizens are so angry they’d almost like to string the kid up.” Aunt Margaret’s upper lip curled in that all-too-familiar way. “Gads, all this business of digging up burials, old bones … it’s just so ghoulish.”

“Especially if people go digging up bones in your backyard, right, Aunt Margaret?” I chirped.

“Particularly when it happens in my backyard!” she agreed.

Uncle Stuart ruffled my hair and smiled. “Ghoulish to you maybe, but not to a certain twelve-year-old girl.”

“Nearly thirteen,” I added proudly.

“Yes, I stand corrected — a certain brown-eyed girl soon to be thirteen.” Uncle Stuart continued to mess up my hair until it stood on end like a witch’s broom.

Aunt Margaret put the letter down on the kitchen table. “Well, that’s enough of all that. Stuart, I’d like your help in getting these apples sliced up and into the freezer today.”

“What?” I asked. “Is that all there is?” Aunt Margaret was ignoring me. I picked up the letter, and when I got to the part where she left off, I started to read it aloud. “‘Please make sure Peggy reads my article. I thought of her the whole time I was writing it. I heard that an archaeologist will be coming to excavate the disturbed burial soon. It would be a great time for Peggy to come up and check it out herself. And, of course, she could stay with me for as long as she wants.’” I jumped off the seat and started dancing around the kitchen. “Yes, that would be so cool. I’m going to get Mom on the phone and ask if I can go and stay with Aunt Norma.”

“Of course, you can’t go, Peggy,” Aunt Margaret said. “You’ve got school. And it’s just like Norma to forget something like that. No, your job right now is to work hard at school and get good grades.”

Zap! There it was — that familiar feeling of having the life sucked out of me. I loved Aunt Margaret, but she had a knack for crushing every ounce of a kid’s excitement. I glanced at my uncle, who shrugged and offered no help.

“Maybe you can go during Christmas holidays,” Aunt Margaret added brightly.

Right, I thought, like that’s gonna make me feel better.

“Aunt Margaret,” I said, “Golden’s in the north where it gets really cold in the winter. First, the ground will freeze and then comes months of snow. No one will be doing any excavating in December. Besides, by then there’ll be nothing left but a big hole.”

That night when Mom came home from work Aunt Margaret and I pounced on her before she even knew what was happening. After she had a chance to read the letter and Aunt Norma’s newspaper article she said, “I’ll have to think about it, Peggy.”

“Liz, you’re not actually going to think about letting Peggy go up there, are you?” Aunt Margaret’s voice was all squeaky and shrill, the way it got when she was appalled about something. I looked at my mother hopefully, but her face was expressionless as she reread Aunt Norma’s letter.

Just then the telephone rang. “I’ll get that while you three work this out,” announced Uncle Stuart. It was just like him to get out of the way when things started heating up.

“Seriously, Liz, your daughter needs to keep up with her school work. Getting a good education is the most important thing she has to do.” Aunt Margaret folded her arms and had that all-too-common “I’m right” look on her face.

“I agree, Margie. Peggy’s education is the most important thing. But there’s more ways to learn than just sitting in a classroom.”

My mom was so cool. I felt like flying across the room and giving her a bear hug.

“Don’t give me that line about ‘alternate learning methods.’ If Peggy’s going to succeed academically, go on to university one day and then have a decent career, she needs to be in class every day.”

“I’m not saying that learning in a traditional school setting is bad. I’m just saying that the whole world is Peggy’s classroom, and yes, there are alternative ways to learn.”

“Ah, sorry to interrupt,” Uncle Stuart broke in. “Peggy, the phone, it’s for you. It’s Dr. McKay.”

I glanced at Aunt Margaret, who looked as if she’d just stepped in something brown and disgusting. Then I leaped off the chair and grabbed the phone.

“Eddy! How are you? I’m so happy you called…. You’re going where? … I can’t believe you know about that. My aunt just sent us a letter…. Yes, she lives in Golden…. You’re going when? … Do I want to come? Are you kidding?” I cupped the phone. “Mom, it’s Eddy. Get ready for this — she’s been asked by the Archaeology Branch to go up to Golden and do a historical resource assessment. Talk about coincidences! And not only that, she’s going to excavate the vandalized burial in the Golden Pioneer Cemetery before the cold weather sets in. She’s leaving this Wednesday and she’s invited me to go up and help her.”

I couldn’t look at Aunt Margaret because I knew she was wearing one of her frowns — the kind that was meant to make me melt from her disapproval. Instead I just stared into Mom’s smiling eyes.

These past few years had been tough on my mom. When my dad died, she was left trying to take care of me. She had a good job, but then the place closed down. That was why we had to move in with Aunt Margaret and Uncle Stuart. Now that she finally had a new job, we’d soon be able to rent a house of our own in Crescent Beach. And to be honest, as much as I loved Aunt Margaret, I was looking forward to life without her breathing down my neck every day.

Mom grinned. “Peggy, have you, Norma, and Dr. McKay been cooking this whole thing up behind our backs?”

I shook my head furiously. “Honestly, Mom, before Aunt Norma’s letter came this morning, I knew nothing about the entire thing.”

“Well, if you ask me —” Aunt Margaret began.

“Thank you, Margie, but I’m not asking you this time,” Mom said firmly.

Oh-oh, I thought, someone’s going to pay for that. As Aunt Margaret’s face turned bright red, Uncle Stuart quietly ducked out of the room.

“No, this has to be my decision,” Mom continued as she wandered to the window and stared out as though studying the clouds while Aunt Margaret’s barometer edged up and steam began to pour out of her ears. “Okay, here’s the deal, Peggy,” Mom said finally. “You can go to Golden with Dr. McKay and stay with Aunt Norma for as long as it takes to finish the excavation. But you’ll be expected to keep up with your math, spelling, and grammar.”

I nodded eagerly like one of those bouncing dashboard puppies.

“And that’s not all. When the excavation’s complete, I expect you to write a report for your teacher on what you and Eddy learned — a history report on the life of Golden’s pioneers. Now, if you can promise to do all of that, as well as help Dr. McKay, then you can go. Deal?”

“Yippee, it’s a deal!” I screamed, forgetting that I was holding on to the phone. “Oh, sorry, Eddy, did I hurt your ear? I’m just so happy. Mom says I can go.”

For the rest of the day I was like one of those windup toys that never stopped moving. And it only got worse after Mom called Aunt Norma to tell her I’d be coming to stay with her. After supper I reread my aunt’s letter and newspaper clipping three times and even made notes.

The next day Mom took me to the bookstore and we bought a couple of math and English workbooks. I didn’t even complain when we got home and Aunt Margaret handed me two more she just happened to have. Right!

On Wednesday morning Mom stood in front of me with a list. “Okay, have you packed enough socks and underwear?”

“Check.”

“Did you put in five pants and five tops?”

“Check.”

“A couple of warm sweaters?”

“Check.”

“Good, and here’s the pajamas I just washed, your raincoat, and your boots. If there’s anything we forgot, you’ll have to borrow it from Aunt Norma.” Mom sat on the bed and smiled as though remembering something. “Gosh, I just realized the last time you stayed with Aunt Norma on your own was when you were two years old. It was before your father died and he and I had the chance to go on a company holiday to Hawaii. Norma offered to look after you. Do you remember that?”

“Ah, Mom, I was two. What’s there to remember?”

Mom laughed. “Well, maybe it’s just as well you don’t remember. It would only embarrass you.” She began stuffing my things into the backpack on my bed.

“What do you mean, it would embarrass me? What happened, anyway?”

She started doing her snorting giggle thing, which always made me laugh, too. “Oh, dear, it was so hilarious. It was the day before we were to get home from our trip and you’d gotten into Aunt Norma’s preserved plums and eaten an entire jar. By night you’d pooped your way through all the diapers we’d left for her. In a small town the stores close early, so she got the idea she’d make a diaper like the Kootenay First Nations once used — leaves, cottonwood seeds, and animal hides.”

At this point in the story Mom was holding her sides and barely breathing. “You’ve got to give her credit. If nothing else, Norma’s innovative. So she went out and gathered the largest and softest leaves she had in her garden for padding your bottom, and since she didn’t have any animal skin, she cut holes in a plastic bag for your legs and tied a ribbon around your waist to keep it all together. By the time we arrived, you’d pooped your way through all her spinach, collard, and kale — and, oh, your poor little bottom was covered in a rash and stained green for days.” She was right. That was an embarrassing story. And between that and my mom, who was laughing like an out-of-breath hyena, I, too, was nearly rolling on the floor.

“Well, there’s definitely not going to be any plums this time,” I said. “But just in case, I’m putting in five more underwear.”