Читать книгу Ginger Baker - Hellraiser - Ginger Baker - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

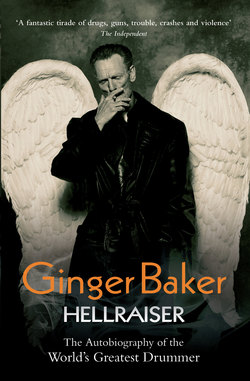

Phil Seamen

ОглавлениеAs a kid, I’d listened in awe to Phil playing with the Jack Parnell Orchestra and I always felt that he was without a doubt the most talented drummer ever to come out of Europe. As I moved on to the modern jazz scene in 1959, I was lucky enough to see Phil play many times. He was the only drummer using the ‘matched grip’ and I shamelessly copied this right away. The things Phil could say with his drums brought tears to my eyes. His drums spoke eloquently and they always told very moving tales. It just flowed out of him, everything tied together and I thought of Phil as the Drum God.

I’d been hanging out with Dave Pearson and one night we went into Jackie Sharpe’s. We sat down and at the next table but one to us was Phil, with the saxophonist and bandleader Tubby Hayes and bassist Stan Wasser. The great Phil Seamen was sitting just a yard away from me! I couldn’t help but gaze at him in awe. I would never have dreamed of speaking to him because I imagined how it would have gone:

‘Hi, Phil, I’m a drummer and a big fan of yours. Got any tips?’

Phil’s reply, I’m sure, would have been the same one that I always give, which is: ‘Yeah, fuck off!’

But, a few months later, I landed a cool gig as part of the regular rhythm section for the Jazz Session at the Flamingo all-nighters, along with Johnny Burch on piano and Tony Archer on bass. I’d been playing there for some weeks when Tubby Hayes heard me, rushed up to Ronnie Scott’s and told Phil to get down there and ‘cop the drummer’. I had snorted a jack beforehand and walked off stage at the end of the set to be confronted by the Drum God.

‘’Ere! I wanna talk to you,’ said God and indicated for me to follow him outside.

We emerged from the basement club into a chill and drizzly early morning in London.

‘Where the fuck did you come from?’ he demanded. ‘What’s yer name?’

‘Um, Ginger Baker,’ I replied.

‘Ginger?’ His voice showed scorn. ‘No. What’s yer real name?’

‘Peter,’ I replied.

‘OK, Pete. Forget the fucking Ginger bit, your name is Pete. Now listen. You can play the fucking drums – I mean, you can play.’

Right away, I felt like I was 50 feet tall! God had said I could play! Phil then produced a battered joint from his raincoat pocket, lit up, took a huge toke and passed it to me.

‘What’re you doin’ right now?’ he asked.

‘Nothing.’

‘OK, let’s get a cab to my place. There’s some stuff you gotta hear.’

We got a cab to Phil’s basement flat in Maida Vale. As soon as we entered, Phil got out a pile of 78s and put them on his gramophone (this was 1960!). The unique sound of the Watusi Drummers boomed into the pad.

Then Phil got out some little pill bottles that were just like Dickie Devere’s. He put a few jacks into an empty bottle followed by a large dob of glistening white powder. He then fitted a needle on to the end of an eye-dropper with the aid of a strip of cigarette paper, drew some water into the works from a glass on the table, squirted it on to the mixture in the bottle, struck a match and held it under the mixture till it boiled. He then sucked the mixture up into the works and tied a handkerchief tight around his arm. I watched in amazement as he tried to find a vein. His whole arm was a mass of dark-red tracks.

‘When I tell yer, pull this,’ he said, indicating the end of the handkerchief. This was to release the tourniquet. After quite a while, he exclaimed, ‘Now, Pete – quick!’

I pulled the tag and the handkerchief fell off. Phil squirted some of the mixture into the vein then paused and released the rubber so blood reappeared in the works, then squirted in again. He repeated the process several times. This was the first time I witnessed someone have a fix.

‘Nah, Pete, I gotta tell you this – this fucking stuff is bad fucking news. Don’t you ever, ever try it.’

I didn’t dare tell him that I’d snorted a jack just a few hours before. His attention turned to the drumming on the gramophone.

‘OK, Pete, where’s the beat?’

I listened and tapped 1, 2, 3; 1, 2, 3.

‘Nah, nah, nah, it ain’t. Listen.’ Phil then started tapping a slower pulse to the drums 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4. I joined in and for the first time I felt the pulse of Africa.

‘Yeah, Pete, I knew you’d get it!’ said Phil happily. ‘I fuckin’ knew it when I heard you play. If you only knew the number of drummers I’ve tried to show that to, you wouldn’t believe it!’ He looked very pleased, and record after record went on the turntable. A door had opened, a light had gone on, Africa was in my blood and I couldn’t wait to play my drums. Then, as we listened, the calendar on the wall suddenly moved downwards about two feet!

‘The bastards are there again!’ yelled Phil and he grabbed a shovel and ran outside.

I followed him, puzzled. What on earth was going on? By now, it was daylight and the garden was deserted.

‘They’re spying on me,’ Phil declared, without letting on just who ‘they’ might be.

He then showed me the warning system he had rigged up, which consisted of a fishing line running from the garden gate along an intricate series of hooks and bends to the calendar. If the gate opened, then the calendar moved downwards. I suggested that it was probably a cat, but Phil was having none of this. He remained convinced that he was being spied upon.

By then, the drizzle had cleared and I walked home along Kilburn High Road in the early-morning sunshine with the drums of Africa still thundering in my ears. I was going over 12/8 rhythms to the 4/4 of my footsteps. What a momentous day! When I got in, I made a cup of tea and told Liz about my great night with the Drum God.

I saw a lot of Phil over the next few weeks and he taught me a great deal. We worked together on his practice pads, which consisted of a large book wrapped in a towel. He was a wicked teacher, though, and would whack me across the back of the hand with his stick if I got things wrong. This seemed to work as I didn’t make too many blunders.

Then Phil came up with a suggestion. He told me he was moving into the flat of Eddie Taylor (another very good drummer) on Ladbroke Grove and suggested Liz and I move in with him. Liz was heavily pregnant and the landlords at Mowbray Road had told us we would have to move out because they didn’t want kids in the place. This appeared to be an ideal solution, so we moved into the roomy basement flat at the end of November 1960. Shortly after, Jackie Maclean, another heavy junkie, also moved in. I was still picking up my daily jack from Dickie but keeping it a secret from Phil.

Life quickly became very chaotic, to put it mildly, because Phil and Liz did not get on. Phil hated women and truly was a confirmed misogynist. He had once been married to a beautiful dancer but she had been screwing other guys while he was on the road and the break-up of his marriage (so he told me) had led to his addiction. Jackie and Phil would also have very loud arguments in the early hours and the flat was, in Liz’s words, ‘absolutely filthy and unsavoury characters turned up at all hours’.

A junkie friend of Phil’s, who was a regular visitor, ran in the front door one day and announced, ‘There’s a taxi outside and I’m not paying it,’ then rushed out of the back door, leaving Liz to placate the driver. Some days later, we read in the paper that a drug addict had murdered a doctor in his surgery and got away in a taxi that he hadn’t paid for. It was junkie lunacy so Liz packed her bags and went back to her mum’s. I spoke to Liz on the phone daily as the baby was nearly due. I was torn between her, who I loved, and Phil, who I was learning so much from. Then Jackie split as well.

Phil had many hilarious turns of phrase, or ‘Philisms’ as I came to call them. He called orchestra conductors ‘spastic windmills’. He was a member of the ‘die trying squad’. A ‘khazi dweller’ was a junkie, living in a toilet. ‘Fred Karno’s army’ stood for an untogether team or unit; an ‘’arris’ was a bottom (Aristotle: bottle, bottle of rum: bum). ‘Dodgy mincers’ came from ‘mince pies’ meaning eyes. ‘Golden bollocks’ was a lucky man and ‘Mustapha Piss’ was an Indian prince. Finally, ‘The Lord said to Moses, “Come forth,” but ’e came fifth and lost ’is beer money.’

Phil played the drums in the orchestra pit for the West End production of West Side Story. One evening, at the most dramatic moment when one of the characters is murdered, Phil began to nod off and the tympani player leaned over and whispered, ‘Phil! The bell!’ Phil woke up, hit the large gong, stood up in the pit and announced loudly, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, dinner is served!’ The corpse on stage began to shake with laughter, as did the rest of the cast and the audience.

One morning, when Phil was out, I found a couple of jacks on the floor. I picked them up and without much thought I skin-popped them as this was the latest way of taking them that Dickie had got me into. When Phil returned, he took one look at me and just exploded.

‘You’re fucking stoned!’ he shouted.

I couldn’t deny it and finally admitted to him that I’d been using for quite some time. He was actually crying and he suddenly looked very old and deeply upset.

‘Oh, Pete, you stupid bastard!’ he said.

Then the phone rang and it was Liz’s mum Ann, saying that the birth was imminent. I rushed out of the flat to the tube and then ran all the way from Neasden station to the house at 10 Elm Way. Dr Wills and the midwife were there, but the baby was not. Dr Wills put me in charge of the gas and air machine and I held the mask to Liz’s face. She started giggling, and very soon, with no screaming or yelling, a baby girl was born. I felt as though I was watching a film. Remembering the attempted abortion, I anxiously counted all her fingers and toes, but everything was normal. Ann then rushed in with her cat in her arms.

‘Get that bloody cat out of here!’ snapped Dr Wills.

Thus chastised, Ann returned minus the cat. It was 20 December 1960 and we named the baby Ginette Karen. However, Liz and I didn’t get much sleep that night because little ‘Nettie’ proved to have powerful lungs and wailed continuously. At about 3am, I took the squalling little girl in my arms and walked over to the window.

‘If you don’t stop howling, you little sod, you’ll go out of this bloody window!’

Nettie proved to be pretty bright, because she stopped crying and I gave her to Liz who took her in her arms and finally we all slept cuddled together.

I was 21 and a father. Phil’s words were still ringing in my ears and he was in such a dreadful state himself that Liz had named him ‘The Awful Warning’. I decided – no more smack. I took to drinking spirits to carry me through and by Christmas I was feeling fine.

Through an old school friend, Liz found us a maisonette in Neasden close to her parents. We moved into 154 Braemar Avenue, a ground-floor place with one bedroom, a sitting room, kitchen and bathroom. The rent was £14 a week.

At the next all-nighter, I met up with one of my biggest fans, a very jovial character called Ron Chambers, who always sat in the front row at gigs. He had confided in me that he carried a gun and was a hit man for the Kray brothers. He gave me a fiver for the baby. He also gave us tins of powdered baby milk on a regular basis when we were very skint.

I was now earning just over £20 a week working virtually every night, but we were still only just managing to get by. I couldn’t even afford a pound to spend on a jack and that helped me to stay straight for a good couple of months. But unfortunately the die of addiction was cast and I often found myself wishing that I could do a jack before a gig.

One night, I met Dickie in Sandwiches and he asked why he hadn’t seen me for a while. I told him about the baby and the rent.

‘’Ere! Come with me,’ he said and led me to the khazi where I skin-popped a jack.

I returned to the jam with the wonderful blinds coming down behind my eyes and played the best set I’d played for months.

Afterwards, Dickie gave me a small package of silver paper containing three jacks. ‘There’s a little present for ya!’ he said.

I snorted one before the gig at Ronnie Scott’s the next night, but, although it felt good, a little voice in my head was telling me that I needed a works. Phil came into the club the next night and I asked him if he could get me one.

‘Listen, Pete, I ain’t giving you one,’ he replied angrily. But after a time he relented and put his arm around my shoulder. ‘If you’re going to do this,’ he said resignedly, ‘you might as well do it right!’ He told me to come back to his place and said he would take me to see a doctor first thing in the morning. Back at his flat, he lent me a works and I skin-popped another jack. There was a female junkie there who Phil introduced as Rutter.

‘So, you’re getting registered tomorrow?’ she said conversationally, as Phil was making the tea. ‘Tell her you’re using more than you are. That way you can sell what you don’t use.’ Then she asked me how much I was using.

‘About six jacks a day,’ I lied – it sounded good!

‘Ask the doctor for three of each,’ she instructed. ‘Three grains of heroin and three of cocaine.’ I had never used cocaine, but she told me not to mention this to Phil and arranged to meet me at a cafe on Baker Street at ten-thirty the next day.