Читать книгу The Sierras of Extremadura - Gisela Radant Wood - Страница 10

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Ancient footpaths lined with yellow broom, purple lavender and white cistus lead in and out of dark pine woods that provide cool shade. High rolling pastures, bright with wildflowers, are framed by snow-capped mountains which puncture the blue sky. The white-washed, red-roofed buildings of small villages can be seen tucked into the folds of hillsides. Cows graze the lower slopes and the valley floor, their bells providing the only intermittent sound; griffon vultures circle above the peaks. There is not another person in sight.

Extremadura remains Spain’s least-known and least-visited region, but very gradually, walkers, lovers of nature’s beauty and seekers of peace are finding their way there. Many arrive not knowing quite what to expect. None leave disappointed.

The region is sparsely populated in modern terms: it has only 26 residents per square kilometre, while England has 406. The largest city in Extremadura is Badajoz with a little over 150,000 inhabitants. Most people live in small towns or villages each with their distinct character and quite separate from the next. Ribbon development does not exist in Extremadura.

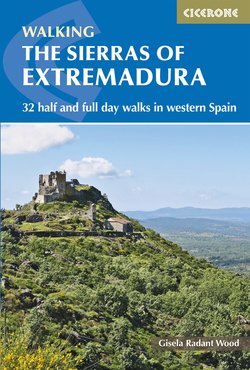

Walking down to Puente Sacristán (Walk 10)

What does exist, in abundance, is open countryside, mountains, hills, valleys, lakes, rivers, forests, pasture and thousands of kilometres of paths criss-crossing the region. These paths are perfect for walking: some are part of an ancient communication network from the days when people walked everywhere; some are delightful meanderings around the agricultural areas that surround every village. The oldest are paved with granite, others are soft earth. Many are shaded with trees and have verges profuse with flowers, in season.

The untouched countryside is a haven for wildlife and birds, and Extremadura has many protected areas. Monfragüe National Park lies at the heart of where the Tiétar and Tajo rivers meet; the area is covered in forest and is famous as a nesting site for many species of raptor. Further west, where the Tajo crosses into Portugal, the Tajo International Natural Park has been established where the rivers Erjas and Sever join the bigger river. The oldest rocks in the peninsula sit in the middle of the Cáceres plain, and the Monumental Park of Los Barruecos has spectacular granite rocks of at least 575 million years old. Its lakes attract birds year-round.

Cornalvo Natural Park is, in reality, a huge area of dehesa – open parkland covered with spaced-out evergreen holm oaks. Its lake, formed by a dam built in Roman times, attracts birds and wildfowl year-round. La Garganta de los Infiernos Natural Park in the Jerte valley incorporates part of the southern slopes of the Sierra de Gredos, while as recently as 2011 a GeoPark was formed uniting the areas of Las Villuercas, Los Ibores and Jara.

All of these parks have hundreds of kilometres of designated and signed walking paths and are testimony to Extremadura’s continuing commitment to preserving its natural environment.

A chance meeting in the Sierra de Gredos in June

The biggest Protection Areas are, without doubt, for birds. These have the acronym ZEPA (Zona Especial de Protección para Aves); the Sierra de Pela and the Sierra Grande de Hornachos, both featured in this book, are ZEPA areas. The Sierra de San Pedro and much of the area around Cáceres are also designated ZEPA.

Quite apart from its natural heritage, Extremadura also boasts three World Heritage Sites: Roman Mérida, Renaissance Cáceres and Guadalupe. These cities, along with Trujillo, Coria, Plasencia, Badajoz and Jerez de los Caballeros, to name but a few, are wonderful places to explore on foot and soak up the atmosphere of past centuries. However, Cáceres, Mérida and Badajoz also have their dynamic, modern sides, which can add a different dimension to a walking holiday.

Geography and geology

Extremadura sits west of Madrid and east of the Portuguese border. It is the fifth largest autonomous region in Spain and is divided into two provinces: Cáceres and Badajoz. At 41,633 square kilometres it is just larger than Switzerland. From the border with Castile and León in the north to the Andalucian border in the south is 280 kilometres. On a map the region looks like a layered cake: from north to south are the Sistema Central mountains, the Tajo river basin, the Montes de Toledo, the Guadiana river basin and the Sierra Morena.

Granite boulders are a feature of almost every walk in the northern and central sierras

Across the north, within the Sistema Central, lie the Sierra de Gata, Sierra de Béjar and the Sierra de Gredos. These forested sierras contain the highest peaks in Extremadura, reaching over 2000m. They are snow-covered for up to six months of the year. Springs that well up high in the sierras are engorged with snow melt and form numerous rivers which keep the valleys permanently green.

South of these mountains lies the Tajo river basin with its main tributaries: the Tiétar, Alagón, Almonte and Ibor. The Tajo is the longest river in the Iberian peninsula.

Strung across the middle of Extremadura are the Montes de Toledo with numerous smaller granite sierras. Some, such as the Sierra de San Pedro in the west, are low hills rather than mountains, but the Sierra de Montánchez reaches a respectable 994m.

The mountains in the Sierra de las Villuercas are not granite; their geological structure is mainly composed of slates and quartzites and the walking experience is very different there. The sierras run parallel to each other, largely ruling out circular walks. The Almonte and Ibor rivers, which flow north to feed the Tajo, rise in Las Villuercas while the Ruecas and Guadalupe rivers are tributaries of the Guadiana river to the south.

The Guadiana is also fed by the Zújar and Matachel tributaries and forms part of the border between the two provinces. As it flows west and turns south it becomes the border with Portugal. The river feeds the Orellana canal system, which irrigates thousands of hectares of agricultural land producing maize, rice and tomatoes among other crops.

The Sierra Morena, with peaks over 1000m, lies to the south and straddles the border between Extremadura and Andalucia. The sierra is made up of granite and quartzite, as well as softer materials such as slate and gneiss. While on average 1000m lower than the peaks in the Sistema Central, the Sierra Morena is nevertheless an important mountain range within the overall geography of Spain. It provides the watershed for two of the peninsula’s five major rivers: the Guadiana to the north of the sierra and the Guadalquivar to the south.

The Jaranda Valley near Guijo (Walk 14)

Animals and birds

The wildlife in Extremadura is still genuinely wild. Depending on the habitat and the time of the year that you visit, red deer, wild boar, rabbit, Iberian hare, fox, badger, wild cat, pine marten, genet, otter and mongoose may be seen. Lynx are much rarer.

Extremadura has long been known by birdwatchers as a very special place. It is on many migratory routes, with diverse species stopping off in summer or winter. Cranes feed in their thousands in wetlands. Storks make nests on every available high spot on churches and castles alike. The mountains provide habitats for many species of vulture, eagle, harrier, buzzard, kite and hawk. The forests house pigeons, doves and woodpeckers – very often heard but not seen. The river valleys are home to the heron, stork, lapwing, grebe, ducks and any number of smaller water-loving birds. The open expanses provide homes to great bustards, especially in La Serena in the south-east of Extremadura. The general countryside is full of azure-winged magpie, colourful bee-eater, flashy hoopoe, crested lark, shrike, golden oriole, dove, owl and many small songbirds.

Griffon vultures can be seen from many of the walks in this book

Flowers and plants

Extremadura’s natural habitats support an enormous diversity of flowers, flowering bushes, trees and vegetation. In spring it is impossible to do many of the walks in this book without stepping on carpets of colour created by thousands of wildflowers: Barbary nut, Spanish iris, field gladiolus, foxglove, asphodel, birdsfoot trefoil, snake’s-head fritillary, lupin, yellow and white daisy, vetch and orchid. The distinctive purple that covers the dehesa in April and May is courtesy of viper’s bugloss.

Clockwise from left: Cystus Albidus; aricia Agestis on a Leontodon Hispidus; lichen on granite boulder; sawfly orchid (Ophrys Tenthredinifera)

Poor soil and stony sierra slopes are no barrier to tough but beautiful bushes: white and pink flowering cistus, white and yellow broom, retama, lavender, Mediterranean Daphne, Spanish heath, rosemary, juniper and tansy. They form a backdrop to the walks in spring and early summer.

Agriculture has provided numerous trees that add their own colourful blossoms in spring: olive, cherry, orange and almond trees have been cultivated for over a millennium. The sight of the Jerte valley in spring, covered in cherry blossom as far as the eye can see, is unforgettable. The leaves of the fig trees of Almoharín give shade in the summer, and in the winter their bare branches add a sculptural structure to the countryside.

Within the huge forests are the indigenous oaks – holm, cork and Pyrenean. Spanish chestnut, terebinth, alder and a variety of pine underpin the diversity of trees so important to the ecology of the area.

Human history

During the long Stone Age, small clans of hunter-gatherers arrived in the Iberian Peninsula, as evidenced by cave paintings in the region. By the Bronze Age, settlements of livestock herders, agriculturalists and harvesters were established. In the Iron Age separate societies emerged.

Rock painting, Sierra de Peñas Blancas (Walk 27)

The Phoenicians were the first traders to reach up the rivers into the area that would become Extremadura. They were followed by the Greeks, whose main trading partners were the Celtiberians, a group of distinct and merged tribes of Iberians and Celts. They had arrived, possibly from Gaul, in sporadic waves between 3000 and 700BC. The Lusitani, who settled on both sides of the River Tajo, and the Vettones, their allies, who settled in the Alagón valley, along with the Turduli/Turdetani were the principal tribes occupying Extremadura. The countryside is littered with the reminders of their tradition of building dolmens to bury their dead.

The Carthaginians followed the Phoenicians around 575BC. They were originally happy just to trade, but after they lost the First Punic War to Rome (264–241BC) they established a small military presence to salvage their pride. The Lusitani and the Vettones were not about to let that happen: for over 30 years they resisted the Carthaginians in a sustained guerrilla war.

The Romans came to Iberia to fight their enemy the Carthaginians. After defeating them the Romans looked around at the wealth of the region – mainly in agriculture but also in metals and marble – and they stayed. They established camps, built defensive forts and intermarried with the local population. The capital of Lusitania, their westernmost province, was established at Ermita Augusta, today’s Mérida. After the Roman Empire fell, the Visigoths held sway from early AD400 to 711 when the first of many invasions by Arab and Berber tribes, collectively known as the Moors, started. It took the Visigoths, mixed with peoples from the north of Spain and reinvented as the Christians, 500 years to reconquer Extremadura.

Horses are still a part of everyday life for many local people

In the 1500s, Extremadura provided the majority of conquistadores for the plundering of the New World. Trujillo and Cáceres still display the results of some of the wealth brought back, but most of the treasure went to fighting interminable religious wars. Extremadura gradually slid into obscurity; the landlords lived as landlords do while the people worked the land in abject poverty.

The Peninsula Wars of the early 19th century ravaged the land. The forces of Spain, Portugal and the British on the one hand, and Napoleonic France on the other, pillaged their way through the region. The 20th century brought no respite: the civil war saw defeat for republican-minded people. Dictator Franco took his revenge in neglect of the area for decades. Many people sought work in other European countries; people over 60 may not speak English but very often have enough Dutch or German to pass a pleasant time of day with visitors from those countries.

Today, modern roads and investment in agriculture and tourism have brought a new dynamic to the region. The people of Extremadura are genuinely open and friendly. They are fiercely proud of their home villages but are well aware of what is going on in the wider world. However, the care of the family, the village, the countryside, the traditional way of life: this is what matters to modern local people.

There is a growing realisation that the region’s centuries of isolation have handed down a precious heritage. Enormous tracts of Extremadura are still untouched. Active conservation has, so far, kept at bay 21st-century manias such as unsightly and noisy wind farms. Power demand is met with solar panel farms, which are silent, less intrusive and allow the sheep to graze the land as they have done for centuries. The future of Extremadura looks good. Long may its beauty be enjoyed while also being protected.

Getting there

By air

Extremadura has no international airport. Most visitors fly to Madrid, Lisbon or Seville and hire a car. Hire cars are available from the big car rental companies at all three airports, or visitors who prefer not to drive from an airport city can take the train or bus to Extremadura (see below) and hire a car locally. See Appendix D for car hire contact details.

To Madrid

Madrid’s airport – called Adolfo Suárez Madrid-Barajas – is perhaps the obvious choice as it has the most direct daily flights connected with the most destinations. BA-Iberia (www.britishairways.com) connect to almost everywhere in the world and are competitive in their pricing with off-peak bargains. However, not all regional airports have a direct flight; many have connections in London’s Heathrow or Gatwick airports.

Madrid is well served by several low-cost airlines: both Easyet (www.easyjet.com) and Ryanair (www.ryanair.com) offer flights from all the major airports in Europe, and some regional airports have limited flights. Vueling (www.vueling.com) and Norwegian (www.norwegian.com) are both low-cost airlines gaining in popularity. Vueling tends to fly with a stopover in Barcelona, its hub. Both Vueling and Norwegian run limited flights in the winter months.

Lufthansa (www.lufthansa.com) and KLM (www.klm.com) are medium-priced airlines that fly to Madrid from a staggering number of places, although some have connections and stopovers at other airports.

To Lisbon

Lisbon is well served by all the above-listed airlines, as well as Portugal’s own airline, Tap Portugal (www.flytap.com).

To Seville

Seville is the least well served airport. BA-Iberia operate there with daily direct flights from London Gatwick, but flights from Amsterdam or Berlin, for example, are via Heathrow or Gatwick. Easyjet also fly direct to Seville daily from Gatwick. Ryanair provide a daily flight from London Stanstead and Brussels, while Dublin fares less well with three flights a week.

All information is correct at the time of writing (2017) but it is vital to do your own research.

DISTANCES TO EXTREMADURA TOWNS FROM MAJOR AIRPORTS

Madrid to Gata – 330km

Madrid to Jerte – 235km

Madrid to Guadalupe – 260km

Madrid to Monesterio – 460km

Lisbon to Gata – 330km

Lisbon to Jerte – 424km

Lisbon to Guadalupe – 410km

Lisbon to Monesterio – 355km

Seville to Gata – 375km

Seville to Jerte – 380km

Seville to Guadalupe – 325km

Seville to Monesterio – 98km

By rail

Trains from Europe arrive in Madrid at Chamartín Station. From there, take the Metro (subway) to Atocha Renfe, look for the Cercanías platforms and take a Cáceres–Mérida–Badajoz train. Get off at Navalmoral de la Mata or Plasencia for the northern sierras; Cáceres for the central sierras; Mérida for the southern sierras. See bus and car hire information to get from these towns to the walks.

There were no direct trains from Lisbon that stop in Extremadura at the time of writing (2017). Trains from Seville go to Mérida, Cáceres and beyond but need connections. For more information see www.renfe.com.

By bus

Buses run from Madrid’s Estación Sur. The Metro stop is Mendez Alvaro. A number of bus companies go to different parts of Extremadura. Avanzabus (www.avanzabus.com) run a service from Lisbon but with limited stops in Extremadura; there is a good bus service from Seville. For useful websites see Appendix D.

By car

Drivers entering Spain from the north should head for Burgos, Valladolid and Salamanca and pick up the N-630 Ruta de la Plata or the E-803/A-66 motorway (they run side-by-side but are not the same). Extremadura is reached through the Puerto de Béjar, where it is possible to stop and enjoy some walking in the Ambroz valley or continue on to the chosen destination.

Driving in Extremadura is a real pleasure as there are so few vehicles on the roads in comparison to almost every other European country. It has some of the best-kept motorways in Europe but they are usually only two-lane. Smaller roads are well kept but village streets are generally tiny and confusing. The Guardia Civil make regular checks on vehicles at roundabouts so make sure yours is roadworthy and that your licence and ID are in order to avoid the on-the-spot fines.

Local driving habits are civilized and mainly polite, although the tradition on roundabouts of keeping to the lane on the right, no matter whether turning left or not, is confusing at first. The roads around villages tend to have slow-moving tractors and trailers during December and January for the olive harvest, during June and July for the tomatoes and fruits and August for the figs. Be patient.

By ferry

Brittany Ferries (www.brittany-ferries.co.uk) sail from Portsmouth to Bilbao and from Plymouth to Santander. Once there, head for Burgos, Valladolid, Salamanca and follow the Ruta de la Plata down into Extremadura. From Bilbao to Hervás in the Ambroz Valley is 500km and from Santander to Hervás it is 470km. Add an extra 285km to drive down to Monesterio.

If you want to bring your own vehicle and tour Extremadura it is a good way of travelling to the area.

Getting around

The most practical way to get around Extremadura is by car. The network of motorways and main roads in Extremadura is excellent. Minor roads linking small villages are generally good and the drives can be very scenic.

Folk music is an important part of any local fiesta

The rail company Renfe (www.renfe.com) runs trains that link all the main cities across Extremadura, and main railways stations have bus connections. Spanish trains usually run on time and every ticket holder has a seat. Train fares are reasonable – 300km between Madrid and Cáceres is around €40, with discounts for young people and students. Over 60s can buy a Trajeta Dorada (Golden Card) for €5 at any railway station by showing their passport or proof of age. This card allows immediate discounts on all rail travel. (Prices correct in 2017.)

Plasencia, Cáceres, Trujillo, Mérida and Badajoz all have main bus stations. Even the smallest villages from which walks start and finish have bus stops, although services may often be limited to one bus per day in each direction. Note that services can be disrupted at any time and on public and local holidays they do not run at all. Getting around by bus is in theory a good idea but in practice may be complicated.

See Appendix D for contact details of local transport providers.

When to go

March and April are normally warm and sunny with occasional showers, and are lovely months for wildflowers and nesting bird activity. May and June still have flowers but can be hot and dry, while July and August are very hot and walking is only possible early or late in the day – preferably by a river or under shady trees in the northern sierras. Things have cooled down by September and October but the countryside stays dry until the rains come – generally October/November. All of Extremadura can be enjoyed in November and December: they are glorious months with the forested slopes of the sierras ablaze with autumn colour. There may be rain but not usually for days on end, and migrating birds visit the region at this time. January and February can be cold with showers, but flowers start to bloom along with the almond blossom. Snow is not usual in the central and southern sierras, but in the north the sierras can be freezing with substantial falls of snow.

Always check the weather before setting out – try www.eltiempo.es (search for villages individually to get local forecasts).

March in the Sierra de Gredos

Bases and accommodation

Bases

Extremadura is vast. The walks in this book are grouped around central places to stay, which should aid planning and, in some cases, make daily transport arrangements unnecessary. There are tourist information offices in most of the towns, and places that do not have a dedicated tourist office usually provide tourist information at the town hall. See Appendix D for contact details.

Northern sierras

In the Sierra de Gata, San Martín de Trevejo, Gata and Robledillo de Gata are charming old villages with historical character, pleasant squares, places to eat and a few shops. They all offer a good choice of accommodation.

The small village of La Garganta offers no accommodation but Baños de Montemayor and Hervás, both within easy distance of La Garganta, are thriving tourist centres with excellent facilities including banks, cash machines, shops, restaurants and tourist offices.

La Garganta

Jerte is a popular and busy tourist town with good facilities and accommodation options to suit all pockets. It is especially pretty – and busy – at cherry blossom time of the year (April/May) so book early. Jarandilla de la Vera is also an excellent tourist centre with a variety of accommodation, including the 15th-century Parador de Jarandilla de la Vera. The tourist office has plenty of information on local routes for walkers.

Central sierras

Montánchez and Almoharín are small towns with banks, shops, cafés, bars and restaurants. They offer a quality choice of village and rural accommodation. There is no tourist office that covers the area, in spite of advertising that there is, but the local town halls are helpful, especially in Almoharín where English is spoken.

Guadalupe is an international tourist centre. It has a hospedería and a parador as well as numerous hotels and casas rurales (see ‘Types of accommodation’, below). The tourist office is very good and well stocked with information leaflets and maps of local walks.

Southern sierras

Alange, La Zarza and Hornachos are good places to stay with a full range of facilities and accommodation choices. Mérida, the capital of Extremadura, is also not far from these towns. The tourist offices, especially in Mérida, are useful places to visit.

Monesterio is an excellent base for walking and offers a variety of accommodation. The tourist office, run by Enrique, where English is spoken, is sited in the Jamón Museum which is certainly worth a visit.

Types of accommodation

Hospederías are usually situated near an area of tourist interest but could also be found within quite a large town. They are government-owned and -run hotels of good quality and facilities at a medium price range: around €75–€125 per couple per night including breakfast. They can be modern buildings or well-converted old properties.

Paradors are also government-owned and -run but are definitely in old historic buildings such as convents, monasteries and castles. They are usually situated in older parts of historical towns. They are sympathetically converted but retain many original features to give an atmosphere of comfort but within a slice of history. The price range in Extremadura is between €150–€230 per couple per night including breakfast.

Casas rurales can be almost anything from a grand estate farmhouse to a modern house but are usually situated in the countryside or in a small rural village. They are graded with oak tree symbols – one is basic, two is medium and three is superior. Casas rurales can be rented in different ways:

rent the entire building and be completely self-sufficient

rent the whole building but breakfast is provided and rooms are cleaned

rent a room and share the kitchen and other common rooms with other people (whom you will not know) who are also just renting rooms

rent a room but the owners live in the building and provide breakfast and clean the rooms.

Prices vary from around €35 per person or €50 per couple per night, including breakfast, up to over €100 for luxurious and well-facilitated places. It is important to research casas rurales carefully but many are fabulous places in beautiful locations.

Many hospederías and paradors offer reduced prices mid-week, Tuesday to Thursday. Some of the offers can be half-price so it is worth doing some careful planning in advance.

Recommendations for accommodation throughout Extremadura can be found at www.walkingextremadura.com/where-to-stay.html.

Food and drink

Black pigs at Monesterio (Walk 30)

Extremaduran (Extremeño) food is delicious and healthy. It is a region whose biggest economy – and export – is agriculture. Not to be missed are jamón (ham) from Montánchez and Monesterio; Torta de Casar sheep cheese; figs (especially the chocolate variety) from Almoharín; cherries from the Jerte valley; raspberries from La Vera; jams from Guijo de Santa Bárbara; and red wines from Badajoz province – especially Monasterio de Tentudía in the blue bottle.

November is the time for mushrooms and many towns do mushroom tapas trails. During the winter months, local hunters provide restaurants with game for their huge stews of venison, wild boar, rabbit, partridge and other game birds – delicious, organic and fresh.

Try to avoid the tourist plazas in the large cities and opt, instead, for the places the locals eat. Most small villages will have a bar that offers food, even if it is only tapas. Others offer raciones – intended to be smaller than a meal but often just as huge. Bear in mind that bars may keep vague hours.

Local cafés and bars open early; 6.00 am is not unusual. They serve coffee and breakfasts, which can be anything from churros (doughnut pastry sticks), to tostadas, with cheese and ham or the traditional olive oil and tomato paste.

Village shops close on Saturday at noon and do not reopen until Monday at 10am. They will stay closed on public holidays and puentes – days that bridge holidays and weekends.

The best tapas are often found in village bars

Language

Castilian Spanish is the language used in Extremadura, although you may well wonder if this is really the case when you’re in conversation with a local. The Extremeño dialect is difficult to follow and the ‘s’ at the end of many words disappears altogether. However, the people are friendly and patient and will wait happily while you try out your Spanish – although their answer may not be so slow. The words habla despacio (‘speak slowly’) are handy. Many people involved in tourism do speak some English, though.

Money

Spain’s currency is the Euro. Avoid high denomination notes when paying cash in village shops and bars. Credit and bank cards can be used in towns in major supermarket chains. Paradors and hospederías will accept card payment for accommodation but some casas rurales may want cash. ATMs are widespread but not in every small village, so plan ahead.

Communications

As a general principle, the bigger the town, the better the communications. Smaller villages nearly all have one public phone box and a post office (the latter often only open from 8.30am to 9.30am, Monday to Friday). Mobile phone coverage is widespread but this can fluctuate in mountainous regions – although in the author’s experience all the walks in this book seem to be covered. Internet coverage is available in most hotels and casas rurales, but if a daily connection is important to you, check before making a booking.

What to take on a walk

Everyone has favourite bits of kit they like to take on a walk, but a few items are common for an enjoyable – and safe – walking experience:

map, compass, GPS device, mobile phone, torch, knife

basic first aid kit; plasters, antiseptic cream, bandage

mosquito and insect repellent

camera, binoculars

hat, sunscreen and sunglasses (useful all year round)

waterproofs

appropriate footwear: should be able to cope with a mixture of terrains – granite can be slippery when wet and harder soles are not a good idea.

comfortable clothing made of natural fibres

walking poles (optional)

water: essential year-round – at least 1L per person

high-energy snacks: chocolate or dried fruits

Waymarking

Of the waymarking you’re likely to encounter on walks in this guide, ‘GR’ refers to Gran Recorrido, a long-distance footpath with numbered stages and white and red waymarks; ‘PR’ refers to Pequeño Recorrido, a short-distance footpath that is numbered and signed in white and yellow; and local routes are indicated by the letters ‘SL’, Sendero Local, with white and green waymarks.

Important routes may have their own fingerposts at junctions. Some routes have helpful hand-painted signs and arrows on walls or gates, while others simply have cairns – which are excellent indicators, especially on higher, wilder sierras.

In recent years there has been a huge improvement in waymarking, but many routes remain patchy or unsigned.

Signage comes in many forms in Extremadura

Maps

The maps provided in this book should be all that you need to complete each walk. However, the relevant Instituto Geográfica Nacional (IGN) map is listed in the information given at the start of the walk. Maps can be purchased directly from IGN, or from other retailers such as Stanfords. See Appendix D for contact details.

The following maps are useful for the walks in this book:

IGN 573 Gata 1:50,000

IGN 576 Cabezuela del Valle 1:50,000

IGN 681 Castañar de Ibor 1:50,000

IGN 706 Madroñera 1:50,000

IGN 707 Logrosán 1:50,000

IGN 730 Montánchez 1:50,000

IGN 803 Almendralejo 1:50,000

IGN 897 Monesterio 1:50,000

IGN 573-111 Eljas 1:25,000

IGN 599-II Jarandilla de la Vera 1:25,000

IGN 652-IV Campillo de Deleitosa 1:25,000

IGN 730-III Montánchez 1:25,000

IGN 830-111 Hornachos 1:25,000

A good road map for getting around Extremadura is Extremadura – Castilla-la Mancha – Madrid Michelin Regional Map 576.

Health and emergencies

There are no major health risks in Extremadura. There are non-venomous, timid snakes but you are unlikely ever to see one. There are also scorpions: do not move stones or rocks or put your hands in dry stone walls. If stung by a scorpion, do not panic – it is painful but not fatal. Go to a health centre for treatment to avoid infection. Wasp and bee stings are no more dangerous than at home.

None of the walks in this book are perilous, but anyone can have a fall or an accident. In case of emergency, call 112. If you know your GPS location simply give it to the call centre. Rescue from the higher peaks is by helicopter; for non-emergencies walk into a local health centre and you will be seen. Minor problems are treated free of charge at health centres but you should be prepared to show your European Health Insurance Card (EHIC). (British people can apply for an EHIC here: www.gov.uk/european-health-insurance-card; those from other EU countries should consult the relevant government website.) Pharmacies also deal with minor injuries.

Consider taking out general-purpose travel insurance that covers walking activities before you leave home.

DOS AND DON’TS

Never, ever light a fire in the countryside.

Take all your rubbish with you (but fruit peels and organic waste are fine to bury).

If you go through a closed gate, close it behind you. In general, leave gates as they are found.

If walking through an area grazed by cattle, just walk quietly and calmly. The cows will be used to walkers but may be protective when they have calves. There should be no bulls on any public paths. Do not walk with dogs.

Do not worry about farmers’ dogs. Aggressive dogs will be tethered; the rest will be bored looking after sheep. Never raise a stick to a dog as it will become confused. Just walk on calmly.

Using this guide

The 32 walks in this guide are grouped under three headings: the Northern Sierras, the Central Sierras and the Southern Sierras. Within each part the sub-sierras run from west to east. Each walk has its own information box with starting and finishing points, how to access these by car and where to park. (Information about travelling by bus in the region is given in the introduction under ‘Getting around’.) The information box also covers the distance of the walk, an estimated walking time, accumulated ascent and descent and a short description of the terrain encountered. The walks vary between 6km and 19km and all but two are circular. A table in Appendix A summarises the walks to help you choose.

Some walks can be linked together to form routes of up to 28km (see Appendix B for a table of linked walks). All involve some ascending and descending but not mountain climbing – they are all definitely walks!

Each walk is described in detail and is accompanied by a map at a scale of 1:50,000, which shows the route and significant landmarks or features. These are shown in bold within route descriptions to aid navigation. A few notes on natural and historical information and what to look out for along the way are also included.

The following are definitions of English words and often-used phrases in route descriptions:

Lane – usually in reasonable condition, made either of concrete or compacted stone and earth. Normally near a population centre and is for use by vehicles, horses, bikes and people.

Track – made of almost anything and encountered mainly in the countryside. Wide enough for transport suitable for the terrain, plus horses, bikes and people.

Path – anything from granite-paved or very rocky to grassy or earth. Much narrower than either a lane or track and is for horses, donkeys and people.

Stream bed – dry or wet, depending on rainfall during the previous winter.

Wall – dry stone unless otherwise stated.

A word about names

Wherever possible, names for sierras, rivers and roads are the ones that appear on the most up-to-date maps. However, some names have been chosen to reflect common usage and do not appear on maps other than in this book.