Читать книгу A New Shoah - Giulio Meotti - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

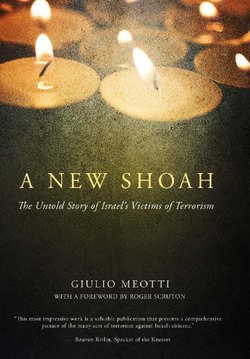

ОглавлениеThe Unsung Dead of Israel

“He said that while it was true that time heals bereavement it does so only at the cost of the slow extinction of those loved ones from the heart’s memory which is the sole place of their abode then or now. Faces fade, voices dim. Seize them back . . . . Speak with them. Call their names. Do this and do not let sorrow die for it is the sweetening of every gift.”

CORMAC MCCARTHY, THE CROSSING

“Just as for the victims ofthe Holocaust we say ‘every Jew has a name,’ so also the victims of terrorism today have names.” The words are from Uri Baruch, a French Jew born to Holocaust survivors, who lost a daughter in a terrorist attack. It was September 20, 2001, nine days after the assault on the Twin Towers in New York. The Baruch family had gathered to celebrate the Jewish New Year in Hebron, the city of the patriarchs south of Jerusalem. Together with Uri and his wife, Francine, were their daughter, Sarit; her husband, Shai Amrani; and their children: four-year-old Zoar, two-year-old Ziv, and Raz, just three months old. Sarit wanted to go back to their home in Nokdim, in the Judean desert. Francine convinced them to spend another night in Hebron because it would be safer for them to make the drive in the daylight. They left at dawn the next day.

A little while later, Uri received a telephone call from Shai’s mother. She had heard on the radio that there had been a terrorist attack on the road to Nokdim. She had called her son’s home, but no one answered. Uri immediately called Francine, who was working at a medical clinic. She contacted the army, and then called her husband. “You need to come. It’s them.”

On the way home, Palestinians had pulled their car up alongside Shai’s. He had rolled down the window to ask if they needed help, and the terrorists responded with bullets. The first went through Sarit’s heart, killing her instantly. The three shots fired at the children miraculously missed their targets. Shai was struck four times in the throat, once in the heart, and once in the lungs. He spent thirteen hours in surgery and two weeks in a coma. When he woke up, he saw Uri sitting there. “Forgive me,” he said. “I couldn’t save your daughter.”

In Jerusalem, at the Yad Vashem memorial, visitors can peruse the giant archive that houses the names of the Holocaust victims. Of all the monuments dedicated to the Holocaust, which by their nature are monuments of emptiness, these plain walls with their endless expanse of names are the most poignant. They are an authentic hazkara, an act of remembrance. In its combination of breadth and individuality, the litany of those Jewish names creates a physical sensation of the immensity of the slaughter as well as the tragedy that each victim experienced. One comes away with something like a sense of betrayal. The territory of Israel is covered with plaques bearing the names of thousands of terror victims; they are displayed along city streets, in schools and synagogues, in cafes and restaurants, in markets, in parks and gardens. Like pin-pricks of blood, these plaques form a memorial of the Holocaust, not forcefully but with tender love. For me, giving a voice to Israeli families destroyed by terrorism, letting them speak as the memories are beginning to fade and are shared only with loved ones, was a form of incarnation like those stark walls of names at the Holocaust memorial. Uri Baruch explained it to me this way: “Like Sarit’s grandparents, who decided to go on living despite the pain and sadness for their slain families, we also decided to live commemorating our daughter.”

Judaism teaches that there is something primordial behind the name given to a new life that comes into the world. When someone converts to Judaism, he must choose a new name, like Chaim, “life,” Baruch, “blessed,” or Rafael, “God heals.” Rafael was the name of one of Uri Baruch’s neighbors. He was a Jewish convert from Holland, and was killed in Hebron because he was a Jew. Before anything else, the Holocaust was an ontological attack against the Jewish name. In 1938, the Nazi official Hermann Göring ordered that “Israel” be added to the name on identification cards for Jewish males, and “Sarah” for females. The Jews were taken by the millions to anonymous, desolate places, where all of their luggage, letters, and photographs of loved ones were taken away. Then they were separated from their mothers, sisters, children, wives. They were stripped naked, and their documents, their names, were thrown into the fire. Finally, they were pushed into a hallway with a low, heavy ceiling. And they were gassed like insects. The nowhere land of the Holocaust was the engine of extermination for six million European Jews. Islamic terrorism and denial of the Holocaust, which spread through the world like wildfire after September 11, 2001, feed on this annihilation of the Jewish victim.

Even while the threat of a new extermination of the Jews is today a reality and a promise, the custodians of memory in the West usually distinguish between anti-Semitism, which is piously condemned in homage to the Holocaust, and anti-Zionism, a hatred for Israel that is eagerly accepted and propagated. European culture maintains that nothing can be compared to the Holocaust; that the Israelis killed today because they are Jews have nothing to do with their parents killed in the gas chambers; that the anti-Semitism behind the Holocaust is a singular evil of the past, where its lessons may be safely buried. In reality, it is not only a historical phenomenon, but also a terribly modern one; not just a form of obscurantism, but a crime against a people and its descendants, both theological and genetic. It is the same old evil with new, “enlightened” faces.

Being Jewish in the century of Hitler and the Islamic Republic of Iran means having a club membership that never expires. On the contrary, it is carried in a person’s name. When terrorists hijacked a plane full of Israelis in Entebbe, in 1976, they selected hostages by making them state their names, and they detained the 105 Jews aboard. Some of them were concentration camp survivors who had experienced that same kind of selection more than thirty years earlier. One of them, Pasco Cohen, was killed in front of his daughter. When the Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl was murdered by al-Qaeda in Pakistan, the Islamic terrorists forced him to say his name, then those of his father and mother, both Israeli citizens: “My father is Jewish, my mother is Jewish, I am Jewish.” In the grimmest photo, Pearl has his head lowered, a chain around his wrists. A man with his face covered is clutching him by the hair, pointing a pistol at his temple. In another, his bare feet can be seen, a bit of the chain dangling from his oversized sweatpants.

Those bare feet reminded me of a young man named Ofir Rahum, who lived in Ashkelon. One day, he received a message on his computer from an older Palestinian girl who lived in Ramallah. Without telling anyone, Ofir put on his best clothes and took the first bus he could. The girl came to pick him up in Jerusalem. He didn’t even realize when the car entered Ramallah, in Palestinian territory. It is difficult to describe what they did to him. He was Jewish, poor, naïve and innocent. That is why he was chosen as “wood to be burned in hell,” according to the propaganda of the Islamic fundamentalists. They assaulted and shot him. They tied his body to the car bumper and drove toward the city. Then they got rid of the body. That’s how life ended for one sixteen-year-old Jewish boy. Why has Ofir’s story never been held up as an example of what ethnic-religious hatred can do?

Why doesn’t anyone know the name of Eliyahu Asheri? He was eighteen years old, the son of an Australian convert to Judaism. He looked at life with a smile, and was hitchhiking home when they caught him. Whenever a Palestinian dies, even a suicide bomber, the newspapers fall all over themselves to publish his story and photographs. Eliyahu wasn’t even named in the newspapers; they just said “Israeli settler.” He was only a kid, executed with a bullet in the head on the day he was kidnapped. Then the murderers took his identification card and used it to extort money from his family.

If a Nazi officer in Auschwitz had filmed a Jew, before entering the gas chamber, in the throes of physical and psychological suffering, like Daniel Pearl, and had made him say “I am a Jew,” today that video would be shown to students all over the world to explain what racism is. But the stories of Daniel, Ofir, and Eliyahu have been forgotten. Daniel’s father, Judea, should be invited to speak at every school.

The history of Israel has been buried under a mound of falsehood: Israel from the beginning accepted the UN Partition Plan for Palestine and the Arabs violently rejected it. Israel generously offered territory through Ehud Barak’s and then Ariel Sharon’s unilateral withdrawal, and each time received the same response: that the solution isn’t land but Israel’s disappearance. All of Israel’s governments, right and left—from Menachem Begin, giving up the Sinai; to Yitzhak Shamir, attending the Madrid Conference; to Yitzhak Rabin, making peace with Jordan and signing the Oslo Accords; to Ehud Barak, retreating from Lebanon and going to the Camp David summit; to Ariel Sharon, withdrawing from Gaza—all have repeated the word that Israel’s neighbors never say: peace. For a large sector of the Islamic world, the cities, skyscrapers, hospitals, cinemas, and schools on this tiny sliver of land are merely real estate that will be restored to Islam once this malefic form is swept away.

Peace can come only with the recognition in the Middle East of Israel as a national state of the Jewish people; the addition of the State of Israel to all the maps used in schools in the Islamic world; the elimination of the extensive anti-Israeli propaganda campaigns in the Muslim media and schools; the promotion of interactions among scientists, scholars, artists, and athletes; the abandoning of the delegitimization of Israel at the United Nations; the outlawing of terrorist groups devoted to the killing of Israelis and the destruction of Israel; the end of the economic boycott against Israel; the institution of full diplomatic relations with Jerusalem as Israel’s capital; and last but not least, the proclamation of theological fatwas prohibiting the murder of “infidels,” Jews, and Christians.

In 1968, just months after Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War, the American philosopher Eric Hoffer wrote an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times in response to the proliferation of anti-Israel sentiment in the international community. His words now sound prophetic: “I have a premonition that will not leave me; as it goes with Israel so will it go with all of us. Should Israel perish the holocaust will be upon us.” The Jewish condition is again the focal point of an enormous battle of identities. Israel can be threatened existentially because it does not exist on the maps studied by generations of Arabs and Iranians. It can be assailed because its history is denied in Europe—denied as a human occurrence made up of immigration, wars against Arab rejection, the struggle for independence under the British Mandate; denied as a right sanctioned by the United Nations and sanctified by the dignity of its victims. How can peace be constructed in the Middle East if Israel’s victims are forgotten?

Two years ago, in Jerusalem, a terrorist killed eight young Jewish seminarians who were studying the Torah. Afterward, a survey by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research showed that 84 percent of the Palestinians justified the attack. Itamar Marcus, who has spent many years monitoring and exposing Palestinian anti-Semitic propaganda as director of Palestinian Media Watch, maintains that the heads of propaganda for Hamas and for the Palestinian Authority’s TV station—with their televised sermons, cartoons, comic books, and schoolbooks—have created a machine to incite killing similar to that of the Hutu journalists who fomented genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda. The Islamic movement describes the Jews as “children of monkeys and pigs” to be exterminated, just as the Hutu supremacists spoke of the Tutsis as “serpents” to be crushed. European countries first prosecuted hate speech on a par with war crimes during the Nuremberg trials of Nazi officers, and after this in the proceedings at an international court in Tanzania in 2003, when the Hutu journalists Hassan Ngeze, Fernand Nahimana, and Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza were found guilty of using Radio-Télévision Libre des Mille Collines and a biweekly magazine to incite the extermination of Tutsis and publish lists of people to be killed.

Hamas and Hezbollah, two of the terrorist organizations that seek the destruction of Israel, call the Jews “pigs,” “cancer,” “garbage,” “germs,” “parasites,” and “microbes.” Iran’s president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad uses the expression “dead rats.” This terminology is the contemporary version of the Nazi schmattes, Yiddish for “rags.” As the great historian Robert Wistrich has explained, “the Islamic movement calls the Jews ‘children of pigs and monkeys’ because dehumanization comes before genocide.” In Israel, terrorists have killed those who inherited the names of their parents and grandparents murdered in the gas chambers and in the forests of occupied Europe. When the siren sounds on Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, all Israelis stop wherever they are, like statues of pain, because living Israelis feel that they are the continuation of the Judaism that was cut off in Europe. They are linked by an invisible chain that explains to the whole world why Israel exists. It is no accident that the siren is the same one that warns Jews to take shelter in case of bomb attacks.

Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote that it was words, not machines, that produced Auschwitz. The Palestinian historian and TV host Issam Sissalem said that the Jews “are like a parasitic worm that devours a snail and lives inside of its shell. We will not allow them to live in our shell.” This is the basic message conveyed by Palestinian sermons, academic lectures, and even performances for children. On March 12, 2004, in a mosque in Gaza, Sheikh Ibrahim Mudeiris, who draws a salary from the Palestinian Authority, declared, “We will fight the Jewish cancer.” Shortly afterward, dozens of Israelis would be blown up by suicide bombers. In February 2008, Wael al-Zarad, an ulema of Hamas, launched a televised appeal for the extermination of the Jews. A few days later, a terrorist gunned down eight Jewish students.

Al-Aqsa TV, controlled by Hamas in the Gaza Strip, broadcast an interview with two young children in March 2007. “You love your mommy, right? Where is she now?” “In paradise.” “What did she do?” “She chose martyrdom.” “Did she kill Jews? How many of them did she kill?” The children on the program were the sons of Rim Riashi, who on January 4, 2004, had blown herself up at the Erez checkpoint. The five-year-old boy held out the fingers of his hand: “This many.” “How many is that?” “Five.”

For many years, since the Oslo Accords, Israel became self-hypnotized with the fable of a pacified, normalized, territorially integrated post-Zionist society. The dream of peace seemed close at hand, but then collapsed miserably under Islamic genocidal belligerence—a new, potentially fatal chapter in the story of the Jewish people. Over the past fifteen years, the Jewish state has been struck in its most vital and routine places. Scores of young people and children, women and elderly incinerated on buses; cafes and pizzerias destroyed; shopping centers turned into slaughterhouses; Jewish pilgrims picked off with rifle fire; mothers and daughters killed in front of ice cream shops; entire families exterminated in their own beds; infants executed with a blow to the base of the skull; teens tortured and their blood painted on the walls of a cave; fruit markets blown to pieces; nightclubs eviscerated along with dozens of students; seminarians murdered during their studies. Husbands and wives have been killed in front of their children; brothers and sisters, grandparents and grandchildren murdered together; children murdered in their mothers’ arms.

This is the Ground Zero of Israel, the first country ever to experience suicide terrorism on a mass scale: more than 150 suicide attacks carried out, plus more than 500 prevented. It’s a black hole that in fifteen years swallowed up 1,557 people and left 17,000 injured. Israel is a tiny country—a jet can fly from one end to the other in two minutes. If a proportion of the population equivalent to those 1,557 victims were murdered in the United States, there would be 53,756 Americans killed. Israeli figures of those wounded in terror attacks, extrapolated to the population of the United States, would be the equivalent of close to 664,133 injured. Since the beginning of the Second Intifada (al-Aqsa Intifida) in September 2000, more Israelis have been murdered by terrorists than in all previous years of Israel’s statehood. Jerusalem is the suicide-terrorism capital of the world.

The stories told here are breathtaking also in their horror and shock. Israelis are deliberately attacked at the times when the largest numbers of people can be killed and in the most indiscriminate manner possible, in the name of eradicating Jews from the Middle East. A flier from the Ezzedeen al-Qassam Brigades, the military wing of Hamas, shows a drawing of an ax destroying the word al-Yahud, meaning Jews, and says, “We will knock at the gates of Paradise with the skulls of the Jews in our hands.”

There were sixteen million Jews in the world before the arrival of Adolf Hitler; now there are thirteen million. The extinction of European Judaism took place amid the complete and tragic failure of European culture. Today in the West there is a faulty conscience—indifferent to the parade of young Palestinians putting on explosive belts, the daily demonization inflicted on Jews in the Arab world, the crowds delirious over the lynching of two Jewish soldiers who had lost their way and whose dismembered bodies were displayed as trophies. This faulty conscience has obliterated the fate of thousands of Israelis murdered because they were Jews; it has erased one of the reasons for Israel’s existence.

Who in the West still remembers that eighty-six Israelis lost their lives during the First Gulf War, killed by Iraqi missiles, by the panic, by suffocation? Linda Roznik, a ninety-two-year-old Holocaust survivor, was buried under the rubble of her home. The same thing happened to Haya Fried, another Holocaust survivor. During the fighting, the Jews of Israel took gas masks with them everywhere they went. Saddam Hussein had come up with a monstrous idea: people could be gassed in Israel just as in a gas chamber, without being able to lift a finger to defend themselves. For this reason, the Jerusalem Post proposed nominating as “person of the year” the sixty-nine Holocaust survivors living in the south of Israel in run-down apartments without any underground shelters or security exits, bombarded by Palestinian rockets after the Iraqi ones stopped falling— people such as Frieda Kellner, from Ukraine, who had survived the Holocaust but was killed by Hezbollah rockets.

The terrorists have always selected their targets in Israel very carefully, to cause as much destruction as possible. One suicide bomber in Rishon Lezion massacred a group of elderly Jews who were enjoying the cool air on the patio, where they had no protection. And then there are the shopping malls like in Efrat, pedestrian areas like in Hadera, bus stops like in Afula and Jerusalem, train stations like in Nahariya, pizzerias like in Karnei Shomron, nightclubs like the one in Tel Aviv, buses full of students like at Gilo, or of soldiers like at Megiddo, bars and restaurants like in Herzliya, and cafes like in Haifa. The reserve soldier Moshe Makunan had just enough time to ask his wife, “Tell our girls that I love them.”

Two brutal sets of murders took place in November 2002 within a few days of each other. Twelve Israelis were murdered in Hebron; and gunmen entered Kibbutz Metzer, killing five people. Terrorist bullets didn’t differentiate between religious settlers in Hebron and dovish liberals in Metzer. The victims in Hebron were all adults; in Metzer, a mother and her two young children were murdered in cold blood. In Hebron, many of the victims were soldiers; in Metzer, the victims were all civilians.

There is a long, heartbreaking list of teenage Jewish girls whose lives were cut off in a moment by a suicide bomber. Rachel Teller’s mother decided to donate her daughter’s heart and kidneys: “That is my answer to the hyena who took my daughter’s life. With her death, she will give life to two other people.” Rachel wore her hair very short and had a wistful smile. Her friends remembered the last time they saw her. “We said ‘Bye-bye,’ a little bit bored, like it was nothing. Instead, it was the last time we said goodbye to Rachel.”

Abigail Litle was returning home when she was killed. “She loved humanity and nature,” her family said. Abigail was part of an Arab-Jewish project for peace. Her family comes from a community of American Baptists who hold their worship services in Hebrew and call themselves Jewish, but believe in Jesus Christ and practice baptism. Their existence is one little tile in the great Israeli mosaic. “For Abigail it was always important for a person to be valued as a person,” her father said. “She never looked at persons as objects that have to be defined according to their nationality. Now she is in a better place.” Her brother added, “She knew that God loved her, and she loved him, too.”

Shiri Negari’s mother had just taken her to the bus stop when she heard a loud boom. She went back and saw only the smoking remains of the bus her daughter had boarded. Shiri’s sister Shelly was in training at the emergency room that morning. She saw the ambulances arriving but didn’t know that her sister was in one of them. Shiri had long blond hair that she refused to have cut; it was like her trademark. She was a teacher in the army, and she signed her e-mails “Shiri Negari—Voyager in the world.”

Noa Orbach had just left school and was chatting with two friends at the stoplight. A man dressed in black approached them and opened fire on the teenagers. Her teacher said, “Noa was the first to start singing on field trips, the first to help a friend in trouble, the first to raise the level of discussion in class. I knew her for three years, and I was looking forward to the satisfaction of seeing her grow up, seeing what she would make of her life. I can’t believe that tomorrow I won’t see her sitting at her desk.” The newspaper published a card she had created, which said: “Getting angry means punishing yourself for someone else’s stupidity . . . ,” with a drawing of a heart and Noa’s signature.

In almost all the attacks on buses or markets or bar mitzvah celebrations, soldiers have died. The terrorists have never distinguished between “civilian” and “military” victims, because the Israeli army is at the heart of the Jewish state, with its permanent exposure to the Islamist war. There is compulsory military service of three years for men, almost two for women, and reserve duties lasting to age fifty. There are no officer academies, so generals are made by rising up through the ranks. Young men come from all over the world to fight in the Israel Defense Forces; they are called haial boded, lone soldiers. They arrive with no money but plenty of idealism, and are taken in by the kibbutzim, eating with adoptive families on Friday evenings, or they share an apartment to save money. These young men have also died by the hundreds at the hands of terrorists.

“The Israelis were soldiers before they were athletes,” noted Abu Daoud, the architect of the Munich massacre in 1972. “Joseph Romano, the weightlifting champion, participated in the Six-Day War in the West Bank and the Golan Heights.” Soldiers before they were athletes; soldiers before workers; soldiers before scholars of the Talmud; soldiers before craftsmen; soldiers before husbands, brothers, sons. At the funeral of Afik Zahavi-Ohayon, a child who was killed by a rocket, the former Russian dissident Natan Sharansky said, “You must have dreamed of being a hero; you must have dreamed of being a soldier. Here every child becomes a soldier, and the entire country is a front. You fell as a soldier.” Those who have fallen are Israel’s human shield.

Corporal Ronald Berer had arrived from Russia fourteen years before he was killed. His mother didn’t want to see him in uniform; she was afraid. He told her, “Mom, they’re killing women and children. Someone has to protect them. If I don’t do it, who will?” That’s what almost all the soldiers say. Benaya Rein’s mother recalled of her son, “The last time he said goodbye, I said ‘Be careful,’ and he replied, ‘You and Dad have taught me to give everything. But you have to know that sometimes everything really does mean everything.’”

The truth about the broken destinies of these Jewish martyrs is reincarnated in the combination of a name and a place, in a life that continues on the ashes and embers of suffering, in the recollections of the parents and siblings and spouses that I have gathered and presented in these pages. Telling the victims’ stories as one indissoluble chain has been, for me, the only way to keep them from slipping away. Reading these stories is an act of solidarity against the abandonment and dereliction of these thousands of victims, young and old, children and infants, women and men. They were coming from work or from school, going to the cinema or shopping when they passed into the next world, pulverized by an explosion. They were Jews whose only crime was that of “living ordinary lives in an extraordinary country,” in the words of the friends of Motti Hershko and his son Tom, militants of the pacifist left who were blown up on a bus in Haifa.

Gadi Rajwan was an Iraqi Jew who employed seventy Arabs and came from a prominent family known in Jerusalem for its wealth and generosity. He went to the factory every day at six o’clock in the morning and was well liked by his employees. Gadi didn’t even have time to look up before being shot in the face by a young Palestinian who had worked there for three years. At the funeral, Gadi’s father, Alfred, kept shaking his head: “How could it have happened to us, to us who have always worked to do so much for everyone?”

Jamil Ka’adan, an Arab who taught Hebrew and worked as a supervisor in the Arab schools, was blown up in Hadera. “He had never believed in violence. He was a man of peace, and I’m not just saying that because he’s gone,” one friend said. Shimon Mizrachi and Eli Wasserman were killed in an industrial area where many Palestinians worked. Mizrachi’s daughter said that “he helped all the workers; he loved to build and create things.” Every morning he met with his Arab employees. Shimon’s wife recalled that “he had a special relationship with the workers.

He believed in coexistence, and he liked to help people.” His dream was to open a kitchen for the needy.

For a parable of Israel’s condition in the Middle East, you can look to the exchange of one innocent boy, Gilad Shalit, an inexperienced Israeli army corporal held in cruel confinement by a gang of thugs, with 1,400 Palestinian prisoners condemned by the most rigorous processes of justice. Among them were at least a hundred life convicts, murderers, serial killers of women and children. Israel, so small and abandoned to itself, is deeply united around the value of life.

Until now, there was not one book devoted to Israel’s dead. This book is written without any prejudice against the Palestinians; it is motivated by love for a great people in its marvelous and tragic adventure in the heart of the Middle East, and through the whole twentieth century. Every project to exterminate an entire class of human beings, from Srebrenica to Rwanda, has been commemorated in grand fashion; but this does not seem to be allowed for Israel. Throughout its history, a quick scrub has always been made of the blood of the Jews killed because they were Jews. Their stories have been swallowed up in the amoral equivalence between Israelis and Palestinians, which explains nothing about that conflict and even blurs it to the point of vanishing. This book is intended to rescue from oblivion an immense reservoir of suffering, to elicit respect for the dead and love for the living.

Every day in Israel there are memorials for victims of terrorism. It wasn’t possible to tell about all of them. Many families, like the Rons of Haifa or the Zargaris of Jerusalem, enclosed themselves in a dignified silence. In four years of research, the most beautiful gift was given to me by the Israelis who opened their ravaged world and laid bare their sufferings to me, a stranger, a non-Jew, a foreigner. They shook my hand and spoke about their loved ones—the families of Gavish, Shabo, Hatuel, Dickstein, Schijveschuurder, Ben-Shalom, Nehmad, Apter, Ohayon, Zer-Aviv, Almog, Roth, Avichail, and others. I wanted to tell some of the great Israeli stories full of idealism, suffering, sacrifice, chance, love, fear, faith, freedom, and the hope that Israel will triumph in the end.

Lipa lost his entire family in the gas chambers, and then lost a son and granddaughter in terrorist attacks. The English-man Steve, after saying goodbye to his wife, learned to live in a wheelchair along with his daughter, and then built a family larger than before. David lost everything, his wife and four little daughters, and is still heroically able to reveal what it means to be Jewish. There is something contagious about his compassion. After the death of his son, Yossi kept his memory with the wisdom of the psalmist. There is a woman, the wonderful Adriana Katz, who heals civilian victims at the most heavily bombed place in the world, Sderot.

Also among the survivors are the doctors who worked beside Dr. Applebaum, who lived with a defibrillator under his bed, and was killed together with his daughter the day before she was to be married. Arnold, the living testament of two families decimated in the concentration camps, lost his daughter in a restaurant bombing and has honored her memory through acts of “true kindness.” There are incredible people like the obstetrician Tzofia, who lost her father, a rabbi, her mother and her little brother, but today helps Arab women give birth. There’s Ron, whose grandfather escaped from the Nazis and whose daughter was killed on a bus. There’s Yitro, a Torah copyist who converted to Judaism and whose son was kidnapped and executed by Hamas. There are the farming settlers Elisheva and Yehuda, whose family had been lost in Auschwitz, and whose daughter Yael was killed by remorseless terrorists simply because “she wanted to live the Jewish ideal.”

Many victims were settlers, the “colonists,” people who pay a very high price for that kind of life—from political antagonism to an extremely intense relationship with death, but above all a pervasive solitude. The settlements endured hundreds of deaths during the Second Intifada, with the days full of fear, the nights spent standing guard in the isolated houses, the sudden massacres of families, infants and unborn babies, the drives through darkened streets in helmets and bulletproof vests, which offer little protection. The settlers’ lives are simple, faithful, centered on lots of children. Their story is a tragic embrace of religion, compassion, toughness, honor, and fanaticism.

“When ‘settlers’ were killed, it was intolerable to read in the newspapers, stuck in a corner of the page: ‘Settler woman killed,’ or worse, ‘Settler child strangled,’ as if the twofold stigma of Jew and settler made the murder understandable, justified it and dismissed it from our attention,” wrote Claude Lanzmann, the director of the monumental film Shoah. “When the ‘martyrs’ blew themselves up, practically every day and several times a day in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Netanya, Haifa, in the nightclubs, in the markets, on the buses, in the wedding halls and in the synagogues, the event rapidly became routine. This time, it was not the ‘settlers’ who were being attacked, but all of Israel. All of Israel had become a ‘settlement,’ and this procured and carefully administered death meant nothing other than the savage claim of a Greater Palestine, the manifest desire for the uprooting of Israel.”

There’s Steve, whose daughter was “too noble for this world,” and Naftali, who lost a wonderful young son whose idea of paradise was “a Talmud and a candle.” Bernice’s daughter had left her comfortable life in the United States. Their stories speak to us about sacrifice and courage. Tzipi’s father, a rabbi, was stabbed to death, and where his bedroom used to be there is now an important religious school. Ruthie’s husband and David’s brother was a great humanist doctor who treated everyone, Arab and Jew alike. There’s the rabbi Elyashiv, whose son, a seminarian, was taken from him, but who believes that “everything in life makes the strong stronger and the weak weaker.”

Sheila lost her husband, who took care of children with Down syndrome; she talks about the coming of the Messiah. Menashe lost his father, mother, brother, and grandfather in a night of terror, but continues to believe in the right to live where Abraham pitched his tent. Alex consecrated every day to the memory of his beautiful little daughter, nicknamed “Snow White.” Miriam saw her husband, a musician, taken from her after they had come from the Soviet Union. Elaine lost a son during the Shabbat dinner, and for more than a year she didn’t cook or make any sound. Yehudit lost her daughter too soon, coming back from a wedding together with her husband. Uri lost his daughter who volunteered for the poor and who studied the Holocaust, from which her family had miraculously escaped.

Orly had a happy life in a trailer in the Samarian hills until her son was killed, before he could put his kippah back on his head. There’s Tehila, one of those God-fearing but modern women who populate the settlements, who loved the pink and blue plumage of Samaria’s flowers. Dror lost much of his family in the Holocaust, and buried his son with his inseparable Babylonian Talmud. The terrorists took away Galina’s husband after they had left everything in Russia so that their grandchildren could be born in Israel, a story that began with the Stalinist repression. Norman is a rich businessman from New York who gave up every convenience imaginable in order to live in Israel; his wife used to guard Rachel’s Tomb in Bethlehem. There’s also the marvelous Yossi, whose son went out every Friday to give religious gifts to passersby, and sacrificed his own life in order to save his friends. Rina had created a pearl in the Egyptian desert and thought of herself as a pioneer; her son was taken from her, along with his pregnant wife.

With his hymn to life, Gabi has honored his idealistic brother who was murdered at the university. There’s also Chaya, who embraced Judaism together with her husband; conversion for them was “like marrying God.” Dr. Picard left France, where his grandparents had fled from the cattle cars of the Vichy government, only to lose a son at a Jewish seminary. There’s the devout Yehuda, who takes care of the bodies after terror attacks. Finally, special mention should be made of Ben Schijveschuurder, who lost his parents and three siblings at a pizzeria, and who likes to remember his father smiling and making the “V” for victory in front of the gates of Auschwitz.

These stories all speak to us of a state that is unique in the world, born from the nineteenth-century philosophy of secular Zionism, which brought back to their ancient homeland a people in exile for two thousand years and cut down to less than half its prewar size. They are stories of courage, desperation, faith, of defending hearth and home through “honorable warfare” in the only army that permits disobeying an inhumane order. This is the epic of a people that has suffered all of the worst injustices of the world, and is reborn time and again thanks to its moral strength.

One of the most excruciating scenes in Shoah, Claude Lanzmann’s masterpiece, took place in the Polish shtetl of Grabow. In late December of 1941, all of the Jews there were asphyxiated in the Chelmno gas vans, and the Poles of the village took possession of their homes. In front of a beautiful carved door, Lanzmann talks with a rural woman, toothless and with upturned nose, who tells him with complete nonchalance that she lives in a Jewish house. Lanzmann asks if she knew the owners. “Of course.” “What were their names?” Silence. She doesn’t remember. Even their name has been lost. This was the second death of the Jews of Grabow. We cannot leave the Israeli victims of terrorism to the same fate by forgetting their names. Making up for the heartbreaking obscurity of these innocent victims is one of the deepest and truest reasons for the State of Israel to exist. As Gabi Ashkenazi, chief of the Israel Defense Forces and the son of Holocaust survivors, explains it, “In Israel there will never again be numbers instead of names; there will be no more ashes and smoke instead of a body and a soul.”

Where a suicide bomber has struck, the victims are arranged near the carcass of the bus. They are placed in heavy black bags, to which are attached a Polaroid photo, a preliminary report, and a card with a number. Many of the victims still have the number assigned to them by the Nazis tattooed on their arms. If the ashes of the Holocaust have led back to the names of the millions killed, the bodies torn apart in suicide bombings have led us back to the individual destinies of Israel, to a name, to the spirit that illuminated a life—even the small, obscure life of an immigrant, dirt poor, who dreamed of living in that land of refuge. In many cases, the victims are identified by their teeth, by a watch, by DNA or blood analysis. There are mothers who go home from the morgue with just the little pieces of jewelry that had belonged to a daughter. Is there anything closer to the Holocaust than this black hole that swallows up lives with hardly a trace?

Ben-Zion Nemett talks about his daughter who survived an attack on a restaurant in Jerusalem: “Shira told me that when the explosion happened, the children were injured. They were burning. The youngest was crying and shrieking, ‘Daddy, Daddy, save me!’ And her father shouted back, ‘Don’t worry, recite the Shema Yisrael with me. Hear, O Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.’ Finally, there was silence. And I, the son of my father, the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust, who grew up with the Shema Yisrael that the Jews recited before being killed, I heard this same story from my daughter. The camp in Treblinka and the Sbarro restaurant became one and the same thing. A genetic code connects the holy victims of the Holocaust and those of the Sbarro. Holy victims whose only crime was that of being part of the Jewish people.”

As Lanzmann remarked, “the Nazis had to look past the dead.” In Ponari and Chelmno, where Jewish fathers and brothers and sons were forced to dig up the remains of their loved ones so they could be burned in huge open-air incinerators, the bodies were called schmattes, “rags.” Things had to be done without describing them, without naming what was being done. The members of the Sonderkommando in Auschwitz, the team of Jews selected to work in the gas chambers and crematory ovens, had scattered hundreds of teeth belonging to victims all over the camp, so that there would still be some trace of them left. Serious reflection should be given to this image of people sowing thousands of human teeth around the camps. In the extermination camp at Sobibor, where 250,000 Jews disappeared, the gas chambers were replaced with fir trees, planted by the Nazis who were fleeing to the West. Those trees—what is it that nourishes them?

At Sobibor, the bodies had been thrown into mass graves with their heads facing downward, like herring. Withered and dry, they crumbled like clay when touched. The Jews were forced to dig with their hands, and the Germans would not allow them to use words like “dead” and “victims”; they were called “figures,” and they no longer had names or faces. In the air, the flames turned red, yellow, green, violet. The largest bones, like the leg bones, were crushed into fragments by other Jews, and the ashes were put into bags and thrown into the rivers. Poles grew tomatoes and potatoes a few hundred feet from the death machines of Treblinka, where almost a million Jews were killed. Today, hens scamper around where the Sobibor camp once stood. The history of European Judaism did not end with a grave where Jews can now go to pray; the only pilgrimage possible is to contemplate a stormy sky, in pain, anger, and sadness. Likewise, the families of terror victims often have no chance to weep over the bodies of their loved ones. They rush to the place of the attack, only to find a carpet of human fragments.

In Chelmno, 150,000 Jews disappeared in a few months. Where are their remains? It’s impossible to recreate the scene; even the survivors can’t do it. “There was always a great silence, even when they were burning two thousand people a day,” said Simon Srebnik, one of only two Chelmno survivors, who died of cancer in September 2006. “No one shouted; there was great calm and tranquility.” That sensation is relived today in the silence observed on Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, when thoughts turn to the names of the dead, but above all in the silence that follows an attack in the middle of a crowd. Yehuda Meshi-Zahav, the ultra-Orthodox Jew who founded the organization that identifies the victims of attacks, explains that “after the bomb goes off everything is quiet; you can only hear the voices of the wounded. It is in those moments that you know what you have to do: make order before the hysteria explodes around you.” The silence of Chelmno and the silence after a suicide bombing, the Zyklon B of the Nazis and the explosive belts of Hamas have this in common: the total destruction of the victim.

Of the three thousand dead at the World Trade Center, one thousand have never been found—not even through DNA analysis. Three hundred bodies were found at Ground Zero. Few families have had the opportunity to identify loved ones with their own eyes. Memorial services were held without human remains. The harder task was identifying the shredded, charred and pulverized remains of the majority of victims—the most detailed and painstaking identification process. When fires rage and concrete crumbles, consuming most other tissues of the human body, only teeth survive. Israeli forensic experts pioneered the method of identification through dental records. Teams of up to one hundred dentists worked day and night shifts in Manhattan. Others performed the clinical task of extracting from cells the unique genetic recipe that identifies every human being.

In the village of Srebrenica, the site of Europe’s worst mass killing since World War II, Serb troops secretly moved the bodies from one mass grave to another in an effort to hide the crime. The murderers also ordered their victims to change clothes before killing them, to make it harder to investigate the crime. From Srebrenica to Ground Zero and Israel, the annihilation of the victim is the mark of the devil. A Jewish headstone in Ashkelon is marked “anonymous.” It is for an unidentified bombing victim who was buried in Israel in 2002. Fifteen years ago, before DNA analysis, most Jewish victims would never have been identified; they would have been buried in a common grave.

In one attack, two young Israeli women with similar features were killed. When a tearful husband arrived at the hospital, he embraced the wrong woman for several minutes before realizing his mistake and locating the body of his wife. Most of the victims in the Park Hotel bombing in Netanya, many of them elderly Holocaust survivors, were maimed beyond recognition, making it impossible to establish identity by fingerprints or birthmarks, scars or tattoos. Even dental records could not always be used, because in some cases the teeth were damaged by the scorching heat. The blast was so powerful that many relatives arrived at the forensic institute to discover that only a hand was still intact. The doctors and social workers accompanied these relatives as they went to the mortuary to touch and kiss the severed hand or leg in a gruesome and desperate farewell. Sometimes it has been necessary to use mass graves because distinguishing among the remains has been impossible. Speaking about the victims again is a form of vindication. It is the purest meaning of memory.

The hero of the Jewish resistance to Nazism in Europe, Abba Kovner, once said that “we Jews have nothing except for our blood.” The Jewish question emerged in the concrete context of genealogy, of the religious and ethnic identity of a people, the genetic identity: Jewish son of a Jewish mother. Reminding us of this are the terrorists who tie up a Jew in front of a video camera and make him say the name of his mother. Men are “accused of a crime that they did not commit, the crime of existing,” as Benjamin Fondane wrote before he was swallowed up by Auschwitz.

Just as Holocaust survivors never say “I” but always “we,” speaking in the name of the dead, the families of terror victims have found suffering to be a source of unity for a country so often torn by politics. Many survivors of attacks, the families and friends of the victims, have talked about how Israel became so much closer to their hearts when they buried their loved ones. The Talmud says that in Israel, the dead protect the living. After the devastating attack on the Dolphinarium nightclub in Tel Aviv, in June 2001, it was said, “The land is won through work and blood. The more friends you bury in this land, the more it becomes yours.”

The first on the scene after an attack are the thousand-odd volunteers of Zaka. The Israelis call them “those who sleep with the dead”; their own motto is Chesed shel Emet, “true kindness.” They reverently gather every human remain, every scrap of flesh and tuft of hair, so that, in keeping with Jewish tradition, the body may be reassembled and buried with dignity. They are the God-fearers filmed at every massacre, bent over among policemen and nurses, gathering drops of blood, “because all men are made in the image of God, even the suicide bombers, and all of the bodies must be honored, so that God may smile again.” They say that their task is sanctifying the Name—of God, and of the dead—and allowing the fulfillment of Ezekiel’s prophecy according to which the dead will find their bodies in the messianic age, and the divine spirit will breathe in them again. “Son of man, can these bones come to life?” Ezekiel asked. And the bones began to move and reassemble themselves: “The spirit came into them; they came alive and stood upright, a vast army.” In the thick of the extermination, in Dachau, Rabbi Mordechai Slapobersky said, “And the flesh and the skin formed around the dried bones that we left behind.”

It was European civilization that died during the Holocaust, swallowing up all of the Jewish communities in its own nothingness; and after Passover in 2002, when the greatest single massacre of Jews since the Second World War was perpetrated in Israel, the Jewish state became the symbol of a war of civilizations. It is not easy to enter this place where suffering reigns, to remember all the victims of terrorism, the “unknown martyrs” of Israel, as Menachem Begin called them in his memoirs of the Soviet gulags. The region that is revealed to the visitor is peopled by the shadows of the dead, and illuminated by what Abba Kovner called “the candle of anonymity.”

What, over the centuries, has permitted the survival of the most persecuted people in history? What has kept them from depression? After pogroms and repressions, what has driven them to put themselves again at the center of history? The birth of Israel is the only political event worthy of joy, hope, and gratitude in a century that became a slaughterhouse to hundreds of millions of human beings—because the twelve million Jews who insist on living in this world despite the gas chambers and the terrorism are the essence of liberty. Israel teaches the world love of life, not in the sense of a banal joie de vivre, but as a solemn celebration. Israel’s national culture is like a miraculous continuation of the Jewish life that flourished in Israel until the Romans—first in 70 CE and then in 135 CE—reduced Jerusalem to ruins. The miracle was represented in the Israeli men who danced in the streets when David Ben-Gurion proclaimed that the Jewish nation had returned home after two thousand years, and right after the Nazi genocide.

What is the spirit that saves Israel from living under the emblem of fear and allows it to fight? The last protection against suicide attacks is a spontaneous form of civil defense, mainly by newly discharged soldiers and by students trying to earn a living, together with a coterie of middle-aged Russian and Ethiopian immigrants who also need a job. They are, in the words of one security guard, “the bulletproof vest of the country.” Human shields, they stand for hours in the cold or the heat so people can shop, sip coffee, and go about their business without worrying about getting blown up.

Rami Mahmoud Mahameed, a young Arab Israeli, prevented a bomber from boarding a bus, but not from exploding; Rami was badly injured. Eli Federman, guarding a Tel Aviv disco, faced the speeding car of a suicide bomber heading straight for the club and coolly fired, blowing up the car before it could enter. Tomer Mordechai was only nineteen years old when he was killed after stopping a car loaded with explosives that was heading for downtown Jerusalem. Tamir Matan died while preventing a suicide bomber from entering a busy cafe. A suicide terrorist at a shopping center in Netanya left hundreds wounded and five dead, including Haim Amram, a working student who was guarding the entrance to the mall. A pregnant policewoman, Shoshi Attiya, had chased down the terrorist.

While some are heroes, the Jewish victims are almost always defenseless people. Massoud Mahlouf Allon was an observant Jewish immigrant from Morocco. He was mutilated, bludgeoned and beaten to death while giving poor Palestinians the blankets he had collected from Israelis. The disabled Simcha Arnad was blown up in the seat of his motorized wheelchair in Jerusalem’s Mahane Yehuda market. Nissan Cohen was a teenager when he fled from Afghanistan. His neighbors called him “a saint,” noting that “When he heard that people had died in an attack, he wept. He visited the sick and prayed for them.” Nissan opened the synagogue in the morning, and in the evening he went back to turn off the lights. During the daytime he helped handicapped children, and at night he studied the Gemara, the commentary on the Law. A bomb killed him at the entrance to the Mahane Yehuda market.

“The great majority of victims are poor or close to the poverty threshold,” explains Yehuda Poch. “Generally they are people who use the bus instead of a car, they shop at the market instead of the supermarket, and they live here in the poorer neighborhoods or downtown instead of in the nicer suburbs.” Poch works with the One Family Fund, the association that for years has taken care of the victims of terrorism.

The stories of these martyrs speak of something that does not emerge from the brutal statistics on the numbers of victims. The International Institute for Counter-Terrorism in Herzliya, the most important center for analysis in Israel, has calculated that only 25 percent of the Israeli victims have been soldiers; the majority have been Jews in civilian dress. Europeans believe that Israel is the stronger side in the conflict, with the military, the technology, the money, the knowledge base, the capacity to use force, the friendship and alliance with the United States—and that before it stands a pitifully weak people claiming its rights and ready for martyrdom in order to obtain them. But the stories of these victims prove otherwise.

And still, the Israelis have shown that they love life more than they fear death. The buses circulate even if they leave burned carcasses here and there, and the stops are always crowded. The supermarkets stay open. Every time a bomb explodes, the signs of the blast are quickly removed; windows are repaired; bullet holes are patched. The places that were blown up reopen after two days. The terrorists of the “road without glory,” as the Jew and French Resistance member Bernard Fall called it, have killed hundreds of teachers and students, but the schools have never closed. They have killed doctors, but the hospitals have continued to function. They have massacred 452 uniformed Israeli soldiers and policemen, but the list of those who volunteer has never shrunk. They have shot up buses of faithful, but the pilgrims continue to arrive in Judea and Samaria. They have committed massacres at weddings and forced young people to wed in underground bunkers, but life has always won over death. When a terrorist began to shoot and throw grenades into the crowd at Irit Rahamin’s bachelorette party at the Sea Market restaurant in Tel Aviv, Irit threw herself to the ground, and from under the table called her fiancé and told him that she loved him—amid the screams and the dying.

The Jewish martyrs are common people with an identity that exposes them to the slaughter of many centuries. It is a story inhabited by people whose names have been lost or forgotten, as if there were nothing left of all those lives. Every time I encountered difficulty in telling their stories, I remembered the wonderful “iron mama” Faina Dorfman, whose grandfather, a rabbi, was burned by the Nazis in Russia. She lost her only daughter in a nightclub in Tel Aviv, but continues to believe in the Jewish saying Yihye besseder, “Everything will turn out well.” She thanked me for “bringing the truth to the world.” For me, pronouncing the names of Israel’s martyrs was an act of piety—accompanying them to the end, dying with them, so that they remain among us.