Читать книгу Game Changer - Glen Martin - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

Dreaming the Peaceable Kingdom

As Desmond Morris noted, Adamson’s philosophy resonated with younger conservationists and researchers. Iain Douglas-Hamilton, the founder of Save the Elephants, said he was led to his life’s work by Born Free, and this, perhaps, is the greatest legacy of the Adamsons. Douglas-Hamilton’s efforts took the inchoate philosophy of the Adamsons, transferred it to a species even more appealing than lions, and gave it some solid scientific underpinnings.

Douglas-Hamilton took his doctorate in zoology from Oxford and at the age of twenty-three conducted a study on elephant behavior in Tanzania’s Lake Manyara National Park. The arc of his career spanned the African elephant’s greatest crisis to date—the Ivory Wars of the 1970s and 1980s. He chronicled the decline of elephants during this period, a decline that was precipitated in large part by poaching and secondarily by habitat loss. More to the point, he helped make this decline an international media event; he brought the graphic images of elephant poaching to the world, and the world was repulsed. Perhaps more than any other single human being, Douglas-Hamilton helped make the 1989 trade ban on ivory by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) a reality.

The success of the ivory ban has been significant, but its effect may be waning. In the first ten to fifteen years following its implementation, poaching seemed checked, if not scotched. Elephants made significant recoveries in various regions of East Africa. But recent indications are that poaching is once again on the rise—stimulated, in no small part, by Chinese development projects in East Africa. Demand for wildlife products—particularly ivory—among Chinese engineers, construction supervisors, and consultants is high and is being vigorously accommodated. (Ivory objets d’art are still greatly valued by Asian consumers, despite—or perhaps even because of—the CITES strictures.)

In 2006, more than 25,000 kilograms of African ivory were confiscated throughout the world. In March 2008, Chinese authorities seized 709 kilograms of illegal ivory, worth an estimated $6,500 a kilogram. And in 2009, a six-ton consignment of Tanzanian ivory was seized in Vietnam, which has emerged as a major processing center for ivory ultimately destined for China. According to an article by Samuel K. Wasser, Bill Clark, and Cathy Laurie published in Scientific American in 2009, the current death rate of African elephants surpasses their annual reproductive rate.

Certainly, the 1989 ivory ban stands in opposition to history. Ivory has never been a commodity in Africa; it has always been, literally, a currency, one that sometimes has exceeded even gold as a store of value. African elephant ivory was esteemed and traded in Hellenic Greece and was a primary symbol of wealth and prestige in Rome. By the late fifteenth century, it constituted a bulwark of the robust trade between the Portuguese and Indians, commerce that also included spices, silk, and gold. Various East African tribes—the Kamba, Boran, Orma, and, later, Kikuyu—were active participants in the trade, jockeying with one another for dominant positions as wholesalers of ivory and as procurers of slaves for the caravans that hauled the tusks from the interior to the coast. There were no routes suitable for wheeled transport between the ports and the elephant lands, tsetse flies would have decimated oxen and draft horses had such roads existed, and ivory was both bulky and heavy. The only practical way to move the stuff across the rugged landscape of East Africa was to have human beings carry it and travel by shank’s mare.

Most of the ivory was provided by hunting-and-gathering tribes, some of whom specialized in large dangerous game, such as the Wata. Researchers have noted that such highly skilled subsistence hunters often preferred to expend their energy on elephants, which could yield a ton or more of meat with one poisoned arrow, rather than on smaller and more abundant game such as zebras. The ivory was also an incentive, providing a means of exchange for iron, flour, salt, beans, and other goods impossible to obtain in the bush. In South Africa, the quest for ivory drove both exploration and settlement. In 1736, a group of elephant hunters forded the Great Fish River and became the first Europeans to investigate the Transkei. Jacobus Coetsee, also in quest of ivory, was the first Caucasian to cross the Orange River.

Though the emphasis in the ivory trade was on obtaining tusks and moving them to markets, there is evidence that the necessity of protecting the source of the product was acknowledged early on. Strict game conservation statutes were enforced in South Africa by Dutch governors in the mid-seventeenth century. (Those initial policies, however, were not maintained. Thomas McShane and coauthor Jonathan Adams note in The Myth of Wild Africa that virtually all large game had been eliminated from South Africa by the early twentieth century.)

As observed in a thesis by Nora Kelly on the history of game preservation in Kenya, conservationist impulses were particularly strong in the British colonial holdings. By 1888, the Imperial British East African Company, chartered by the British government after the partition of Africa into European estates in 1884–85, established control over the game lands of Kenya, declaring itself a monopoly in the commerce of ivory. It decreed specific measures for the trade, including rigorous conservation measures for elephants. Indeed, the depletion of megafauna in general was a significant concern for the IBEAC’s principals. In an attempt to effect control over the unregulated taking of large game, the company announced to the British Foreign Office in 1891 that it would charge license fees to sport hunters entering its domain: “For regulating the hunting of elephants, and for their preservation, for the purpose of providing military and other transport in our Indian Empire or elsewhere, the Company may, notwithstanding anything hereinfore contained, impose and levy within any territories administered by them, other than their Zanzibar territory, a licence duty and may grant licences to take or kill elephants, or to export elephants’ tusks or ivory.”

Ultimately, the IBEAC failed as both a business and a force for conservation, falling into bankruptcy after seven years because it could not turn a sufficient profit. But the company’s basic commitment to conservation was by no means an outlier’s sentiment at the time. The colonial government, confirming the necessity of tight hunting strictures, assumed control of Kenya’s wildlife after the company dissolved. An international conference on preserving African wildlife in the British capital in 1900 resulted in the London Convention for the Preservation of Wild Animals, Birds and Fish in Africa. The accord was ratified by few European powers and hence had little real authority, but it nevertheless signaled general agreement among the colonizing nations that their purview included the preservation of wild fauna as well as the governance of native people and the utilization of natural resources.

The preservation of game remained a top priority of the British colonial government until Kenya’s independence in 1963, though “preservation” was viewed within a context that placed equal emphasis on a thriving agricultural sector; in other words, if elephants ravaged sisal or lions killed cattle outside the national parks or established reserves, they were eliminated. Similarly, vast numbers of buffalo were shot to reduce tsetse threats, and hundreds of thousands of fecund and voracious Burchell’s zebras were expunged to preserve rangeland forage during dry years. Indeed, the difficulty of maintaining, as Ian Parker has put it, “Pleistocene wildlife amongst Holocene people (and) their agricultural land,” became increasingly evident to colonial administrators through the early decades of the twentieth century. In 1945, the Royal National Parks of Kenya Ordinance was passed, creating a national park system that immediately established itself as a world standard for the preservation of megafauna. Kenya was known for its big game before the ordinance, but the parks transformed the colony into a living metaphor for wild Africa. With the parks, Kenya became more than a European colony, an exotic locale, a place to shoot large, dangerous animals. It became an ideal.

And through it all, big game hunting remained both a cherished Kenyan tradition and a significant source of revenue: wildlife was a profit center as well as a public trust. The parks were acknowledged as proper and inviolate refuges, but hunting, it was felt, also had its place. The concept that individual animals warranted extraordinary effort to protect, that they were worth the expenditure of public funds and labor to nurture at the expense of other conservation priorities, simply did not exist.

Ivory, in particular, continued as the ne plus ultra of both legitimate hunting trophies and illegal wildlife commodities. Indeed, ivory supported Kenya’s drive for independence. Jomo Kenyatta, a Mau-Mau leader and the first president of sovereign Kenya, sustained his fighters in the field by killing elephants for both their meat and tusks. Muthoni-Kirima, a Mau-Mau combatant, noted in interviews that she secured a permit to deal in ivory from Kenyatta once he attained the presidency. She remembered the sites in the forests where the Mau-Mau had buried ivory against future need; returning to them, she exhumed the tusks and legally traded in ivory for some time following independence. Ultimately, Kenyatta issued such collecting permits to a number of favored ex–freedom fighters and allies. There was a good deal of ivory in the bush, mostly from elephants that had died of natural causes, and the permits were a cheap and easy way to generate goodwill and return favors. But the permits also provided a conduit for illicit ivory to the legal market; some collectors killed elephants for their tusks or paid others to do so. Ultimately, these permits created a situation that was to play out tragically.

Meanwhile, conditions were rapidly changing on the lands where the elephants lived. Drought hammered Kenya in 1960 and 1961, particularly in the region that contained Tsavo National Park, a huge protectorate that had been established in 1948. The effective management of Tsavo was problematic from the start. The region was generally sere and poor; indeed, the reason the park had been established was that the land was unsuitable for intensive grazing or cropping. The elephants quickly expanded their numbers past the range’s ability to support them. This was especially the case in the eastern portion of Tsavo. Confined within the park’s borders, elephants monopolized the forage, ultimately destroying the woodlands. Thousands of animals died in the drought of the early 1960s, particularly black rhinos; scant water was one cause, but the lack of vegetation due to excessive browsing by elephants was the primary reason.

And though the rains ultimately returned, the wooded cover at Tsavo East never fully recovered, because elephants were being driven into the park by the growing populations of farmers and pastoralists who lived outside the sanctuary lands. Tsavo’s elephants were increasing but for the wrong reasons; Kenya’s population of elephants was at best stable and possibly declining during this period. Their population was dramatically increasing only in the parks, where the already meager carrying capacity of the land was stretched past the limit. Census flights over Tsavo East, West, and adjacent areas during 1961 indicated the elephant population was at least ten thousand. By 1968, that number had grown to forty thousand. Parker, who was working in the Tsavo area at that time for the Game Department, reported the woodlands “were melting away” as the numbers of elephants expanded. Both game managers and conservationists were split on an appropriate course of action. One camp favored aggressive culling. The opposition, fearing that the abundant tusks resulting from so many dead elephants would prove a corrupting influence and create a boom in the illegal ivory trade, opposed thinning the herds. David Sheldrick, the first warden for Tsavo East, ultimately sided with those opposing culling.

In 1971, drought returned to Kenya—indeed, a good portion of East Africa. The elephants in Tsavo East, overpopulous and already stressed by inadequate forage, died wholesale. Their tusks, representing millions of dollars, littered the park. By this time, an extensive shadow network of illicit ivory collectors and dealers had been established in Kenya, the ultimate result of the ivory permits handed out by Kenyatta seven years earlier.

This army of ivory hunters descended on Tsavo East en masse, spiriting the tusks past the park’s borders to lands controlled by the Kamba, a tribe that was active in the ivory trade. The rains returned to Tsavo in 1972, and the supply of ivory from elephants that had succumbed to natural causes was quickly exhausted by the ivory seekers. But the trade, fueled now by high demand and serviced by a large professional cadre that moved ivory from the field to markets quickly and efficaciously, did not stop. The ivory takers simply shifted from salvaging downed tusks to killing elephants. The Kamba, located hard by Tsavo East’s borders, had always resented the creation of the park on lands that they had traditionally used for subsistence hunting and seasonal grazing. Their transition from ivory gathering to elephant hunting seemed to them natural, a serendipitous economic opportunity and a matter of appropriate recompense for past wrongs. Gangs of Somalis, armed with modern automatic rifles, also intruded from the north and began working over Tsavo’s remaining elephants with dispatch. Nor were government employees exempt from ivory lust. In the late 1970s, staffers from the Wildlife Conservation and Management Department—which had been created by the merging of the Game Department and the National Parks Department in 1976—were implicated in the slaughter of scores of elephants.

By 1975, David Sheldrick’s meager force of rangers was utterly overwhelmed by ivory hunters. Hundreds of poachers were entering Tsavo East every month, and their take of tusks and rhino horn became industrial in scale. In 1975, Sheldrick’s rangers arrested 212 men and recovered 1,055 tusks and 147 rhino horns—products that represented a fraction of the presumed total kill. But their efforts were utterly inadequate to the holocaust that had enveloped them. The great Ivory Wars had begun.

The liquidation of Tsavo’s elephants coincided with the maturation of electronic media. By the final spasm of the Ivory Wars in the 1980s, video images were widely transmitted by satellite, delivered to virtually every TV set in the world. A regional issue that once would have interested only game managers, trophy hunters, and hard-core conservationists became a global story of mass appeal. The video footage of bloated elephant carcasses, of piles of illicit ivory, of heroic wardens with disreputable-looking poachers in coffle, bypassed the intellectual processes and engaged people from the developed world on a visceral level. Intelligence was now widely understood as a salient quality of elephants. Millions of people all around the planet found themselves in instinctive concord with George Adamson: the killing of elephants was tantamount to a capital crime.

The Ivory Wars ultimately drove Kenyatta to declare a total ban on all big game hunting. The 1977 Wildlife Conservation and Management Act must be considered a leap of faith, a last-straw decision made to check an unfolding catastrophe. It was based on anxiety over civil chaos, international pressure from outraged animal lovers, and worries that one of the country’s major economic underpinnings—wildlifebased tourism—was on the verge of collapse. It was not based on science. Indeed, the prevailing view of game managers was that regulated hunting discouraged poaching; armed professional hunters and their clients not only provided essential information to rangers about poaching activity in their blocks but were also significantly more intimidating to poaching gangs than unarmed ecotourists. The emphasis, many wildlife professionals felt, should have been on beefing up the ranger cadre while rooting out the corrupt officials who were part and parcel of the illegal wildlife trade. According to some authorities, Kenyatta considered the act a temporary fix, a measure designed to provide some breathing room until government control could be exerted on the ground. But his long-term strategy remains unknown; he died in 1978, well before any amendment to the ban could be contemplated. And under his successor, Daniel arap Moi, the 1977 act was established as the permanent wildlife policy of the nation. Indeed, the act was hailed as a template for the future by animal lovers—a guidepost for a new, enlightened policy for wildlife management, one that didn’t involve guns or killing.

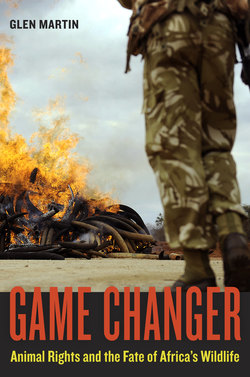

Enforcement of the hunting ban ultimately fell to Richard Leakey, designated by Moi in 1989 as the head of the newly formed Kenya Wildlife Service. It was no coincidence that Leakey’s elevation occurred in the same year as the CITES ivory strictures. (The convention declared that the African elephant was threatened with extinction and listed it as an Appendix 1, or most endangered, species; a complete ban on the international trade in ivory followed in 1990.) Leakey pursued his mandate with vigor, particularly in regard to elephants. He was tireless, widely considered incorruptible, an able administrator—and his rangers had official imprimatur to shoot-to-kill poachers engaged in the field. Shortly after his appointment, Leakey arranged a dramatic public relations coup by convincing Moi to publicly burn twelve tons of captured ivory—the yield of about two thousand elephants. Kenya’s elephant population, which by most estimates had fallen from around 175,000 in 1973 to 16,000 by the late 1980s, stabilized and began a long, though ultimately modest, recovery.

Leakey’s success in temporarily stemming the ivory trade was real; more than that it was necessary, an effective response to an emergency situation. But in a larger sense, it signaled the waxing power of animal advocacy over traditional conservation biology. No African nation had ever attempted a move as bold as a total hunting ban. In the eyes of the world, Kenyatta’s ad hoc response to elephant poaching was transformed into visionary permanent policy by Moi and was justified, given real world credence, by Leakey.

Still, the 1977 wildlife act didn’t accomplish its primary goal: the preservation of wildlife in Kenya. By any analysis, the decline of most game species in the country has accelerated. During the past twenty-five years, there has been a 70 percent decrease in game in the country. Today, no more than 30 percent of Kenya’s wildlife is found in the national parks and the Maasai Mara National Reserve; the remaining 60 to 70 percent subsists on private ranchlands. The hope that ecotourism would provide a revenue stream to compensate for the loss of trophy hunting—and, as a consequence, create strong incentives for wildlife preservation—hasn’t materialized. In some cases, tourism is now the problem. In 1977, the same year the wildlife act was passed, Kenya closed its border with Tanzania. For many Kenyan visitors, the previously unimpeded ecosafari loop of the Maasai Mara, the Serengeti, and Ngorongoro Crater now started and stopped at the Mara. As noted by Martha Honey in her book Ecotourism and Sustainable Development, the spike in visitors to the Mara resulted in a helter-skelter rush to provide lodges, roads, food, and recreational amenities such as balloon rides. The resulting development, driven in large part by Kenyan politicians who profited directly from the ventures, was pursued with little if any thought given to the requirements of migratory game. The visitor boom in turn stimulated additional pressures to expand local agriculture; today, vast wheat fields produce grain where plains game cropped wild grasses a few years ago. The result is that the Mara is in crisis, a fact easily confirmed by the decline in species emblematic of the ecosystem. From 1977 to 1997, the Loita Plains wildebeest herd, which ranges mostly in Kenya and doesn’t penetrate the Serengeti, has dropped from about 120,000 to 20,000 animals. The Nairobi-based International Livestock Research Institute has found that the Mara’s populations of giraffes, warthogs, topi, waterbuck, and impalas have also dwindled dramatically.

Nor has the act truly stemmed the trade in wildlife commodities. As of this writing, the poaching of elephants and rhinos is again on the rise. Field biologists report that trade in rhino horn, ivory, and lion teeth and claws is brisk in the Mara and adjoining lands. Still, it would be erroneous to assume this latest commerce in wildlife parts is a recent trend; rather, it is a continuation of business as usual after a modest downward blip.

The road from Nairobi to Nyeri is one of Kenya’s primary thoroughfares, leading through rich farmland long cultivated by the Kikuyu. The Kikuyu are a populous tribe, and this is their heartland; small, meticulously cultivated farms dominate the hills and valleys, producing an abundance of provender for the nation. There is no wildlife habitat to speak of; as in Langata, though, the opportunistic leopard is by no means unknown. Businesses of every description dot the highway, from simple eateries to vulcanizing shops. (The names of Kenya’s roadside businesses often have a certain skewed or macabre charm: the Mount Kenya Pork Den; the Gender Equity Bar and Restaurant; the Manson Hotel.)

I recently visited one of these enterprises, a curio store, with Rian and Lorna Labuschagne, managers of a large private game reserve in Tanzania. South African by birth, the Labuschagnes have batted about southern and eastern Africa all their lives. For many years, they managed the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. Their interests are catholic and include the collection of African art. Rian had heard this particular shop contained some good masks, and he was anxious to evaluate the wares. “There’s always a lot of junk in these places,” he said as we entered the cool, shadowed interior, a welcome relief from the heat and white glare of the road. “But sometimes you can find some real gems. They tend to pile it all together, and you have to take your time going through it all.”

Rian’s initial take was accurate; most of the items in the shop were pure schlock produced for the tourist trade: rungus (fighting sticks) hastily hacked out of acacia limbs, inexpertly forged pangas (machetes) stuck into uncured leather scabbards, spurious Maasai spears extruded by commercial foundries in Nairobi or Dar es Salaam, carved wood giraffes so alarmingly attenuated they looked like the hack work of a Giacometti understudy. But among the brummagem were a few genuine articles—specifically, several West African masks of great elegance, with the stains of the years on them. There was also something else: a kind of homunculus-like statue, a small, aged, crudely carved manikin that had been fitted with a chimpanzee skull. One arm was raised in a minatory fashion, and the jaws gaped wide. It was an object that seemed to pulse with malevolent force. The Labuschagnes regarded the fetish with neutral expressions. “The only thing remarkable about it is that it isn’t at all remarkable,” said Lorna. “You can find objects like this at shops all over East Africa. The use of animal parts from endangered species never stopped—it never even slowed down.”

In other words, while CITES proscriptions on wildlife products may carry quite a bit of weight in Europe, North America, and other regions of the developed world, they are not much of an issue in Kenya. The trade continues in tusks, lion claws, leopard skins, ape skulls—it’s simply illegal. And that is hardly a deterrent in Africa, Rian observes, given that game law enforcement remains nonexistent to spotty at best and is usually checked by bribery when it does occur. The average Kenyan gains nothing by obeying wildlife regulations, because he or she derives no benefit from observing such laws—a significant issue when annual per capita income is around sixteen hundred dollars. On the other hand, a tusk or serval pelt sold on the black market can provide a significant boost to family income, and a snared impala or speared warthog can represent something of equal value—meat, still a great luxury in protein-poor East Africa.

The 1977 Kenya Wildlife Conservation and Management Act and the 1989 CITES ivory ban were noble in intent, promising a modern retread of the Peaceable Kingdom: not just the lion lying down with the lamb, but also modern human beings lying down with the lion—and the elephant and rhino as well. Kenya, it seemed, could become the place where conservation would transcend itself, become something finer and higher, something rarefied and beautiful. It would become the place where wild animals wouldn’t simply be observed and appreciated; they would be loved.

But a critical component was not addressed in this equation: the people who actually share the land with the animals. In colonial times, conservation laws in East Africa tended to exclude tribal people. To a significant degree, not much has changed; ecotourism in Kenya caters to a wealthy foreign elite, with most of the revenues flowing to the tour companies and political cadres influential enough to seize a part of the action. The people who live with the game—the rural hoi polloi, the average pastoral tribal members who count their wealth in cows and goats—receive little or no recompense. In such a situation, it is no surprise that game regulations are viewed with suspicion, even disdain.

And yet, as Adams and McShane point out in The Myth of Wild Africa, many Africans cherish their wildlife heritage. Tanzania, one of the world’s poorest nations, has devoted almost 15 percent of its land to wildlife parks and reserves; that compares to less than 4 percent of land set aside for the same purpose in the United States. Julius Nyerere, the founder of modern Tanzania, established conservation as a priority in a 1961 speech presented at a conference on natural resources held in Arusha, a town that served as the main entrepôt for safari companies and hunters in the lands surrounding the Serengeti. Nyerere’s presentation became known as the Arusha Declaration of Wildlife Protection, and it set the tone for things to come in the emergent Tanzanian state: “The survival of our wildlife is a matter of grave concern to all of us in Africa. These wild creatures [and] the wild places they inhabit are not only important as a source of wonder and inspiration but are an integral part of our natural resources and our future livelihood and wellbeing. In accepting the trusteeship of our wildlife we solemnly declare that we will do everything in our power to make sure that our children’s grandchildren will be able to enjoy this rich and precious inheritance.”

It must be noted that Nyerere made a subtle distinction between conservation and animal advocacy. Wildlife, he observed, was something that warranted admiration; the game was beautiful, he implied, and deserved protection simply because beauty makes the world endurable. But he also emphasized that wildlife is a natural resource and a renewable one at that. In a country as poor as Tanzania, a resource so rich, so abundant, could not go unexploited. Just as Tanzanians had an obligation to protect wildlife, they also had a right to utilize it. And therein lies the difference between Tanzania and Kenya; in Kenya, the obligation to protect wildlife is acknowledged, but there is no option for legitimately utilizing it.

As of this writing, drought has again blighted northern Kenya. The forage has withered, and the herds that sustain the region’s pastoral tribes have been decimated. People are dying of hunger. Hit particularly hard are the Turkana, a herding tribe with ancestral lands in the northwest corner of the nation. For a Turkana pastoralist whose cattle have perished, whose children are wasting away before his eyes, who lives in a brushwood banda and has no nearby source of water or fuel, the idea of an inviolate wildlife refuge seems an absurdity. On the other hand, this same man likely would support a reserve that would accommodate regulated grazing and firewood collecting, furnish small stipends derived from tourists or hunters, or even provide occasional rations of meat from wildlife culls. To abide in the Peaceable Kingdom, after all, one must have a full belly; otherwise, the lion will be killed and the lamb devoured.