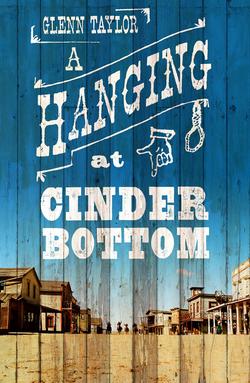

Читать книгу A Hanging at Cinder Bottom - Glenn Taylor - Страница 13

QUEENS FULL OF FOURS February 17, 1897

ОглавлениеIt was Wednesday. Snow had stuck to the mountaintop but not the road. It was the day on which a game of stud poker commenced in Keystone that would last thirteen years. It wasn’t intended to last that long. It was intended instead to carry in the kind of money most couldn’t tote, and it would do so in a quiet fashion, for the game itself was the only of that day’s events not publicized by handbill in the growing town. You must see the lobby to believe it, the papers said. Grand Opening. Alhambra Hotel. It was Henry Trent’s most ambitious project to date, a three-story brick building with four columns in front. He’d built it on the southwest bank of Elkhorn Creek, where the monied folk had moved.

Five men had been invited by courier to sit at the big stakes table. One of the five was Abe Baach, then seventeen years of age. Having already cleaned the pockets of the men at his Daddy’s saloon, he had a reputation. Most had quit calling him Pretty Boy Baach in favor of the Keystone Kid.

The Kid whistled that stale February morning as he walked west on Bridge Street with his arm around his girl. Goldie Toothman whistled too, pressed against him tight for heat. She’d bought him a six-dollar gray overcoat for his birthday to match the stiff hat he wore. The coat was long, well-suited for Abe, who’d stretched to six foot two.

They stopped halfway across the bridge, and though his pocketwatch told him he was nearing late, Abe said he needed to spit in the creek. It was superstitious ritual, but neither of them was taking chances. They regarded the water below, rolling black over broken stones. Along the banks, it was frozen. Brittle-edged and thin and the color of rust.

“I’ll play quick and clean,” Abe said.

“I know you will.” She put her hands inside his coat button spaces for warmth. She kissed him at the collarbone and told him, “Don’t cross Mr. Trent.” She whispered, “Keep your temper.”

He locked his hands around her and squeezed. “Liable to freeze out here,” he said. Beneath her jacket she wore only an old gown. There had been little time for sleep the night before and no time for proper dressing that morning. Sleep came short and ended abrupt when cards and bottles turned till sunup.

Where the crowd grew thick, Abe and Goldie parted. Her Daddy had taken ill again, and she’d have to see about his duties. Big Bill Toothman swept up and kept order at Fat Ruth Malindy’s, a boardinghouse-turned-whorehouse above which he and Goldie lived. Goldie’s mother had died giving birth to her, and Big Bill had raised her alone ever since, with no help from Fat Ruth Malindy, who was his sister-in-law. She was madam of the house and the meanest woman there ever was. So Big Bill got help from the Baaches, whose saloon sat directly across Wyoming Street, where Abe, from his second-story bedroom, had spent his boyhood kneeling at the sill over stolen card decks, knifing seals and opening wrappers like little gifts, shuffling and dealing and laying each suit out to study them. All the while, he waited for Goldie to look back at him from across the lane. From the time he was ten, he’d waited for her, and while he did, he memorized the squeezers from the New York Card Factory, emblazoned in cannons and cherubs and birds of prey and giant fish and satyrs and angelic, half-nude women who fanned themselves with miniature decks of cards. He stole a fine dip pen from his father and began marking them, even recreating their designs on newsprint, down to the tiniest line.

It was Christmas Eve 1892 that Goldie had looked him back.

Now he watched her return to the swinging bridge. He blew hot air into his cupped hands and moved at a fast clip up Railroad Avenue, side-stepping the crowd and walking, without hesitation, between the wide columns and into the kind of establishment only a boomtown could evidence.

The Alhambra’s lobby was indeed rich with curvature and girth. Through the right bank of mahogany double doors was a small auditorium, equipped with a fine stage. A purple felt grand drape hung behind it, a narrow row of gas footlights in front. They were lit for an ongoing opening-day tour of the facilities, and the children of the rich danced before their glow with spotlighted teeth, and one girl fell onto her fragile knees and cried.

At the back lobby wall, a man named Talbert recognized Abe and showed him around a card room with fourteen tables. Each one was covered in fine green billiard cloth. Iron pipes striped the high walls, and twenty or more jet burners lit the place with steady little flames that left no wall streaks. Abe was accustomed to the flat wick lamps at A. L. Baach and Sons, where kerosene smut marked every inch. Al Baach wasn’t concerned with decor. He was content to merely keep open the saloon he’d bought outright in 1891, for the great panic of ’93 had frightened him, and he’d not cleared sufficient money since to renovate.

Abe surveyed the men at their tables, the timid manner in which they moved their wrists and fingers, the slight shiver of their cigar tips.

The smell of good varnish was still on the air.

Talbert asked what his pleasure was.

Abe took the invitation from his pocket and showed it.

Talbert scratched at the mass of greasy hair on his head and squinted at the invitation card. On it was the embossed seal of a round table. “Why didn’t you show me this right off?” he asked. “You’re late.” He told Abe to follow.

They walked across the wide main card room and Talbert tapped five times at Trent’s office door before entering. Inside, it was empty. Wall-mounted gas lamps ran hot. He shut the door behind Abe and pointed to a second glass-paned door at the back. He said, “They’ve already gone through.” When Abe didn’t move, Talbert said, “Go on in.”

When he did, Abe found himself in a room lit by a single lamp. It hung on a hook above the middle of a great big round table fashioned from a white oak tree with a breast circumference of twenty and one-half feet. Four men stood around it talking and smoking. They wore suits. Trent and Rutherford stood in the corner next to a seated black man who was paring his fingernails with a pen knife.

When the door was shut, Henry Trent said, “That makes five.”

Rutherford walked to Abe and held out his hand and said, “Buy-in.”

Abe took the fold of notes from his inside jacket pocket. Rutherford licked his thumb and counted five twenties and said to the black man, “Dealer take your seat and split a fresh deck.”

Abe took off his coat and hat and hung them on one of seven cast-iron coat trees lining the wall.

He and the other four card players took their seats around the table.

The dealer wore a black satin bow tie. His suspenders were embroidered in redbirds. His shirtsleeves were rolled and his fingernails were smooth as a shell. Abe had heard how good he was and had played once or twice with his son.

The man shuffled. He had fast mechanics and a soft touch. “I’m Faro Fred,” he said. “I’ll turn cards till I’m dead.”

Abe sized up the other men. Each of them he knew, whether by face or by name.

They had all heard of him.

Rutherford poured whiskey into a line of cut-glass tumblers with a bullseye design. He set one before each man. Then he sat down in a chair beside the cookstove and took out his chewing tobacco.

Trent said, “If you’re here, I don’t have to explain a whole lot.”

One of the men had a short-lived coughing fit. When he finished, Trent went on. “The game is pot-limit short stud.” He looked each man in the eye. “Go on and buy your chips.” He pointed to the orange glow inside the stove and told Rutherford to tend it, and then he sat down in the opposite corner to watch.

Abe admired the table’s girth and finish. He did not know that it was the very same table where his Daddy had signed his name twenty years before. Do not sit down with Mr. Trent, Al Baach had told him. He does not speak in truths. Abe watched the dealer make his little column of chips and push it forward.

Faro Fred looked him in the eyes, as he did each man to whom he pushed chips soon to be thinned.

Abe straightened his stack and kissed the bottom chip and cracked his knuckles.

He played tight for the first two hours. If his hole card was jack or lower, he threw his two on the pile and spectated. He watched them lick their teeth and grimace and rub at their foreheads and take in their whiskey too quick. He noted the liars and the brass balls. He separated the inclinations of one man from another, and he catalogued who would try to outdraw him when he got what he was after. In the fourth hour, he won a little, twice, on a couple high pairs. Then he lay in wait another two.

His time came when the drunkest man with the deepest stack raised to the limit three straight rounds. Abe followed him where he was going, and when it came time to flip his hole card, with two pairs showing, he turned over that droopy-eyed, flower-clutching queen.

“I’ll be damn,” Rutherford said. “Queens full of fours.”

It had taken Abe only six hours at the table to clean out the best stud poker man in all of McDowell County.

The man’s name was Floyd Staples, and he didn’t muck his cards straightaway. In fact, he flipped his own hole card, as if he believed his ace-high flush might somehow still prevail if only everyone could see all those spades. He watched Abe restack the chips. Staples’ eyes narrowed to nothing. He bit at his mustache and breathed heavy through his nose.

Floyd Staples was unbathed and living in the bottle, and his cardsmanship was slipping. That much was plain to all in the room.

He pointed across the table and said, “This boy is a cheat.”

Abe double-checked his stacks. He’d told Goldie he’d cash out if he got to four hundred. He stretched his back and said to the dealer, “I reckon I’ll cash out now.” He pushed his chips forward, and Faro Fred pulled them with a brass-handled cane.

“Three hundred and seventeen after the rake,” Fred said.

Trent opened a leather bank pouch and counted out the money.

Floyd Staples stood up and smacked the table with the flat of his hand. He looked from Abe to Henry Trent. “You going to let Jew cheaters run your tables?”

Abe stood up. He looked at the expanse of table between himself and Staples.

He straightened his shirt cuffs. He smiled and kept his temper.

It was quiet. Two men took out their watches and looked at their laps.

Rutherford stepped from the wall and handed Abe his winnings.

Abe nodded to him and peeled off two ones. He folded them one-handed, and on his way to the door, he slid them to Faro Fred, who had pitched the fastest cards Abe had ever seen.

It was then that Floyd Staples said, “Baach, I will fetch my rifle and shoot you in your goddamned face.”

Henry Trent quick-whistled a high signal.

Rutherford drew the hogleg from his holster and held it at his side. He told Abe to step back, and then he opened the office door and directed Floyd Staples into the light.

When the door shut behind them, Trent said, “Let’s us all just stretch our legs and visit a minute.”

And they did. They stood up and smoked. Abe spoke briefly with a man in octagonal spectacles who was more refined than his present company. He was not accustomed to threats of death and foot-long revolvers.

Rutherford stepped inside the room again. “He’ll be alright,” he said. “Talbert’ll get him a whore.” He swallowed tobacco juice and coughed into his hand.

Trent said, “Well he damn sure won’t play at this table ever again.” He gave Rutherford a look and turned to the other men. “I apologize for the unpleasantness. You gentlemen play as long as you like. I’ve got solid replacement players ready to rotate. Rutherford will pour your drinks and light your cigars, and if you are in need of company, he can arrange that too.” He put his big-knuckled hand on Abe’s shoulder, opened the door and said, “After you.”

Abe stepped into the office.

Before he followed him through, Trent bent to Faro Fred and whispered a question in his ear. Fred whispered back an answer.

The glass rattled when Trent shut the door behind him.

A two-blade palmetto fan hung from the ceiling on a tilt and did not spin. It was yet untethered to a turbine belt drive. Trent had plans to tether it by summer, when he’d salary a man just to turn the crank. The big bookcase was empty, its glass fronts showcasing nothing. Atop the case sat two cast-iron boxing glove bookends.

Abe sat where Trent pointed, a handsome chair with a green pillow cushion on the seat. It faced Trent’s double- top desk. He stood behind it and shook his head and laughed at the magnificent young man before him. Trent looked ten years younger than the sixty he was, but he knew his face had not ever carried Abe’s brand of chisel.

He opened a drawer and produced a clear glass bottle with no label. “Evening like this one calls for the best.” He set two glasses on a stack of ledgers and unstuck the cork. “You heard of Dorsett’s shine?”

Abe nodded that he had.

Trent smiled. There were two silver teeth in front. His brow had gone bulbous and so had his nose and chin. “You drank it?”

Abe nodded that he hadn’t. He’d only been to Matewan once. Dorsett’s shine didn’t much travel outside Mingo County.

Trent handed over a glass with little more than a splash inside. “Here’s to you,” he said. Then he drank his down and sat himself in a highback chair of leather punctuated by brass buttons. He coughed twice and took a deep breath and smiled.

Abe sniffed at the rim and smelled not a thing. He swallowed it and set the glass on desk’s edge. There was no burn, only a tingle below his bellybutton.

Trent lit his pipe. “Your Daddy is a fine man,” he said.

Abe nodded that he was. He’d long since learned at the card table not to engage in the playing of conversational games, and he’d long since learned not to trust the man who’d promised his Daddy a kind of wealth that was yet to arrive. Al Baach had developed a theory over the years that he’d been bamboozled from the start. Mr. Trent never wires red cent to Baltimore, Al Baach had told his boys. He never sends back Moon’s body. He knew this, he said, because Moon’s own son had told him in a letter. The son was grown now, a good successful boy, Al called him. He warned his boys to stay away from Keystone’s king, and mostly they listened. But Abe was tired of hearing folks complain. Every shop owner and whorehouse madam in Cinder Bottom coughed up Trent’s required monthly consideration with a smile. In exchange, the law left them mostly alone. Some whispered that there might come a time when Henry Trent was no more. Maybe, they whispered, somebody would shoot him, or maybe he’d get choked on a rabbit bone and cease to breathe. But no matter what they whispered, in public they all sang praises to his hotel and theater and all that he and the Beavers brothers had done for Keystone. When the bank had failed the people in ’93, Trent and the Beavers had not. They were the kind of men who kept their money in a safe. And for a while, they gave it out. After ’93, they took to collecting it with interest, and nobody ever had the gall not to pay when Rutherford came collecting. Trent did not himself venture to the other side of Elkhorn Creek any longer. He’d been heard to say that Cinder Bottom wasn’t fit for hogs to root.

The way Abe saw it, Trent could say what he wanted on the Bottom. He’d built it after all. And, the way Abe saw it, Trent knew the path to real money, and the rest of them didn’t. Abe was relatively young, but he saw a truth most could not. There wasn’t but one God, and he was the big-faced man on the big note. His likeness and his name changed with the years, but he maintained his high-collared posture, dead-eyed and yoked inside a circle, a red seal by his side.

He looked across the desk at the older man, who regarded him with humor.

“Your Daddy was here in the early days,” Trent said. “He’ll get what’s due him.” He pointed his finger at Abe. “You tell ole Jew Baach I haven’t forgot.”

It was a name seldom used by that time, a relic of the days when Al was unique in his presumed religiosity. Now there was B’nai Israel on Pressman Hill, a tall stone synagogue equipped with a wide women’s balcony. Attendance was ample, though no Baach had ever stepped inside it. Abe wondered whether Trent even knew of such a place. He wondered whether Trent knew that if he hollered “Hey Jew” on Railroad Avenue, more than two or three would turn their head.

There were those who said Henry Trent’s mind was not what it once had been.

He poured another in his glass and raised it up. “To half-Jew Abe,” he said, “the Keystone Kid.” He stood and went to the corner. He told Abe to turn and face away, and when he’d done so, Trent spun the combination knob of a six-foot, three-thousand-pound safe. He opened the inside doors long enough to put five hundred back in his leather pouch, then he swung shut the safe, sat back down, and took out a sheet of paper and a silver dip pen. “You know I had my money on you,” he said. “Rufus did too. Rutherford had his on Staples, but I had a notion.” He signed his name to a line at the bottom of the sheet. “And do you know what Fred Reed just whispered in my ear?”

Abe nodded that he didn’t.

“He said he’d not seen play like yours at the table since old George Devol.”

Abe had read Devol’s Forty Years a Gambler on the Mississippi nine times through. He’d kept it under his mattress since he was twelve years old, the same year he’d quit school for good. He said, “I aim to best Devol’s total table earnings fore I die.”

Trent laughed. “You aim to live to a hundred do you?”

“Forty ought to do.”

They looked each other in the face.

Trent pushed the paper across the desk. The pen rode on top and rolled as it went.

Abe looked at the figure Trent had written in the blank. $100.00.

“On top of what you take from the table after the rake, I’m prepared to offer you that number as a weekly salary.” He took out his pipe and lit it. “As long as you play like you did in there just now, and as long as you lose to the company men when I signal, I’ll cut you in on two percent of the house earnings, and I mean the tables and the take from stage shows too.” He puffed habitual to stoke the bowl, and his silver teeth flashed. “This hotel will be the shining diamond of the coalfields,” he said. “They will come from New York and New Orleans to sit at my tables and sleep in my beds, and I have a notion they will come to try and beat the Keystone Kid.”

The weekly salary was high—it guaranteed him more than five thousand dollars in one year’s time. But the house cut was low, and he didn’t like the word exclusive on the paper. He started to say as much, but the words hung up in his throat. He cleared it. He said, “Thank you Mr. Trent.”

They discussed his daily table hours and decided he’d think on it until the next morning. Trent produced a fold from his inside pocket and peeled off two and handed them to Abe as he stood from his chair. They were brown-seal big notes.

“For your trouble today,” Trent said.

They shook hands and nodded. Abe excused himself and headed to the lavatory just outside the office, where he stood and breathed deep before putting the money in his boots. For three years, Al Baach had fitted the insoles of his growing middle boy with a thick strip of leather, and he’d told him once, “If you win another man’s money, you put it under there. Then you keep your eyes open.”

He walked through the main card room, past the poor suckers who’d never get ahead, and then through the big lobby, past those busy figuring how they could afford the nightly rate, and despite himself, he could not keep from smiling.

Rufus Beavers stood on the staircase landing. He watched the boy smile and knew he’d lived up to his name at the table. He recognized something in the gait of Abe Baach, something his brother possessed. A sureness. A propulsion that had taken his brother all the way to Florida’s tip, from where he sent home money and word of adventure.

Rufus made his way to Trent’s office, where he found his associate shaking the hands of well-dressed replacement players on their way through the second door. When they were alone, Rufus told him, “Ease up on the Kid’s Daddy. No more collecting.”

Trent furrowed his brow.

“Got to keep Jew Baach happy,” Rufus said. “Otherwise, the Kid will have cause to cross you.”

Trent said, “Having the cause don’t mean having the clock weights.”

Rufus eyed a cigar box on the desk. Its seal was unfamiliar to him. “I wouldn’t bet against the boy’s nerve,” he said. “We’ll need a Jew on council who’s friendly to liquor anyhow, and that boy’s Daddy slings many a whiskey.”

“You plannin to court the Jew vote and the colored too?”

Rufus tried to read the words on the box. Regalias Imperiales. “You know another way?” he asked. “Go outside and look around. Stand there and lick your finger and hold it up. See if you don’t know what way the wind blows.” He opened the lid and took out a long dark cigar. He smelled it and put it back.

Abe had stepped outside the Alhambra’s main doors and was rubbing at the folded contract in his pocket when he noticed Floyd Staples across the way.

Snow fell. Slow, bloated flakes. Staples leaned against the slats of the general store, eyeballing. “I’ll git my money back Baach,” he hollered.

Rebecca Staples stepped from the big door at Floyd’s left. She was one of his two women, a lady of the evening who had worked for a time at Fat Ruth’s. She held their little boy by the hand and he cried and dragged his feet. “I want hard candy,” he wailed. Floyd Staples grabbed him away from the woman and smacked his cheek so hard it echoed.

Abe knew the boy. Donald was his name. Goldie sometimes babysat him on Saturday nights.

He grit his teeth and had a notion to walk over and stab Floyd Staples right then with the dagger he kept in his vest pocket. But he knew better. He’d leave that job to someone else, for surely someone else would have the same notion and the wherewithal to act on it too.

Keep your temper, Goldie had told him, and he aimed to.

The boy, who was only four, went quiet and followed his mother and Daddy, a whore and a drunk, onto a sidestreet where a new apothecary was being built.

Abe walked fast to the bridge, where he stopped long enough to spit at the middle and then kept on, smiling at folks who waved or said hello, nearly jogging when he reached the back of the Bottom. He slowed at the corner of Dunbar and a lane as yet unnamed, a spot folks had begun to call Dunbar and Ruth on account of the wide reputation of Fat Ruth Malindy’s fine-looking ladies.

The snow had quit. There was a wide dull glow of orange behind low scanty clouds. The glow sat slow on the ridge, and the square tops of storefronts lay in shroud.

A black boy walked toward Abe with a canvas bag strung bandolier-style across his skinny middle. “Evenin edition!” he called. “McDowell Times evenin edition!”

Abe fished three pennies from his pocket and held them out.

“Nickel,” the boy said.

Abe regarded his wiry frame. He looked to be about ten years old. “Since when?”

“Since my Daddy proclaimed it so.” He wore a serious look.

Abe put back his pennies and handed over a nickel. “What’s your name?” he asked.

“Cheshire,” the boy said.

“Like the cat.”

He only stared.

“From the children’s book,” Abe said. “But you haven’t smiled once.”

Chesh Whitt didn’t read books for children, but he knew who he was talking to. He’d known from twenty yards off. And he’d rehearsed in a mirror how he’d be when he met the Keystone Kid. He’d be poker-faced with a knack for making money.

“Boy your age ought not be in the Bottom after sundown,” Abe told him before he walked on.

The men gathered out front of his Daddy’s saloon were white and black and Italian and Hungarian and Polish. Some were coming up from the mines and some were on their way down. All were laughing loud at a joke about the limp-dick Welsh foreman with a habit of calling them cow ponies.

A fellow who could not focus his eyes nodded loose at Abe. “I got a good one for you,” he said.

“I heard that one already,” Abe answered. He went inside.

It was an average crowd for Wednesday shift change. A single card game ran at the back, a Russian grocery owner named Zaltzman the only man of six in a suit. A sheet-steel stove burned hot at the room’s middle. It had once been airtight.

Goldie was on the corner stage, and the men stood before her with their hats off, whistling and calling out, “Go again sister!”

She had a crown on her head fashioned from tin and grouse feathers dipped in gold paint. In the center, she’d glued a thick oval scrap of bottle-bottom glass. “Bring em back up to me then,” she answered the men, and they reached inside their hats and brought forth the playing cards she’d thrown.

On the stool at her side there was a long glass of beer. She finished it with great economy and picked up a new deck of cards. “Inspect those comebackers you tobacco drippers,” she called. “I don’t want a card coming back to me bent nor split.” She wore an old set of her Daddy’s wool long underwear, a gold-painted grain bag over that. The bag was big and stiff, her head through a hole in the seam, so that altogether, in headdress and bag, she shone in the rigged pan spotlight as if she’d ridden in on a moonbeam. Queen Bee they were calling her by then, because in Cinder Bottom, at Dunbar and Ruth, that is who she was. Fat Ruth Malindy made the rules, but Fat Ruth Malindy was ugly as ash. Goldie, on the other hand, was a miracle to behold.

On this night her hair was up, spun beneath the crown. She rubbed at her neck where a flyaway hair had tickled, and the men watched, the slope of her shoulder bewitching them. She saw Abe at the door and winked in his direction before getting back to business. “These here cards don’t come free boys,” she shouted to the men. She stuck out her toe and pushed the coal bucket to the edge of the little platform. “Drop in what you can spare now.” A miner just off his shift shoved through and dropped in his change. A house carpenter put in a dollar note and stuck his face out over the stage. He sniffed at her with his eyes shut.

She let him.

Goldie had long since learned to separate a man from his money. There had always been men and money just as there had always been coal trains and mules, and at Fat Ruth Malindy’s, a girl could either go prone and give up her notions of fight or she could learn how to talk to a man and take what he had. Before the age of thirteen, Goldie had twice pulled a skinny whittler blade and touched its point to the groin of a man trying to force himself upon her. By the time she was fourteen, most men knew better than to try. The ladies of Fat Ruth’s admired the girl’s spirit. Some took it up. And there was laughter in that cathouse, and there was always her Daddy, a good man by any measure. And then there was Abe, loyal as they came, quiet when quiet was called for, and, if need be, tameless as the stalking lion.

He leaned against the wall and watched her scale cards. He smiled.

Al Baach stood behind the bar with a rag over his shoulder. He eyed his middle boy, whose path worried him. Al and Sallie had talked on it for years—how the boy was lucky to have Goldie, how Abe and Goldie together were much like Al and Sallie had been twenty years before. But lately there’d been worry, for Al and Sallie had never been quite so old at quite so young an age.

He gave the rag a tug and put it to his nose and blew. He sniffed hard and kept on watching his middle boy. A lad just in front of him let his head fall to the bar top. He was what they called coke-yard labor. He couldn’t have been over fifteen and had come into the saloon already drunk. Al wouldn’t serve him but the lad had stayed put in order to see Queen Bee.

Al smacked him in the ear and said, “Get in your bed to sleep.” The lad was thoroughly awakened, and he stood and walked to the door. On his way, he knocked against Abe, who righted him and headed for the back stairs.

Al called loud to his middle boy.

Abe ignored him. He hit the swinging storeroom door and jumped to the third riser at a run. He took out his key as he went and unlocked the bedroom door upstairs.

He locked it behind him. It smelled like it always had in there. His.

When Abe and his brothers were little, the Bottom hadn’t yet become what it was. Sallie had allowed the boys to be around the saloon, to slumber nights away in its upstairs rooms as their father sometimes did after the boarding house on the hill was booked up perpetual. Respectable boarders would pay a handsome sum to stay up at Hood House, removed as it was from the magnificent filth they so often sought down below. With railroad surveyors and mineral men occupying every open bed, the two oldest Baach boys had moved their playthings to town, where Wyoming Street soon grew awnings to shade its new general store and laundry and tailor shop and tenement-turned-house of ill fame. When Jake Baach was fourteen, he and Big Bill Toothman finished construction of a smaller, second home on the hill, and Sallie aimed to make use of the extra beds, to keep the boys out of the saloon. She aimed to take them from the Bottom altogether, but by that time Abe was a twelve-year-old with the hands of a full-time riverboat gambler. Pretty Boy Baach was good for business. He’d grown accustomed to chewing tobacco when he pleased and playing cards too. School was simple and books had begun to bring on sleep. His head was for numbers. His place was the saloon. He could squeeze tight his mouth and hit a spittoon’s dark heart from nine feet off. He could smell a man’s bluff sweat at the table without so much as a snort.

Too, Goldie lived across the way. None could keep the young man from Goldie.

Abe opened the big wardrobe in the corner and hung his jacket there. He kept his vest on, and from its change pocket he withdrew a small, homemade dagger fashioned from a four-inch cut-spike nail. It was light as a toothbrush, its handle a lashed leather shoelace. He set it on a shelf inside the wardrobe. From his fob pocket, he withdrew the nickel-silver railroad watch his Daddy had given him two years prior. It was Al Baach’s custom to give his boys a sturdy Waltham pocketwatch on their fifteenth birthday. Engraved on the case back of each was the following: A man without the time is lost.

Abe thumbed a smudge on the bezel and tucked it back in the pocket. It was half past six.

He sat down on the bed and untied his shoes. From underneath the inner sole, he produced the two twenty- dollar notes, plus the other bills he’d won, folded lengthwise. He kissed them and then knelt at the open wardrobe, where he reached to the back and undid a hidden latch. Then he shifted the false bottom and lifted it out, his old hidden spot under the slat. He set all the money but one twenty inside with the rest, replaced the slat, rehooked the latch, and sat for a moment on the floor with his back against the wall. He took full breaths and let them out slow.

The game at the Alhambra would bring him what he’d always been after. It was something to ponder.

At the window, cold air issued in at the sill. The shade was half drawn, and below him, folks walked the dirt streets laughing. The restaurant beside Fat Ruth’s radiated the stench of hog fat burned black. The cook stood out front in an undershirt despite the cold. He picked his teeth with a thumbnail and watched the ladies coming to work. There were more than usual on account of the grand opening across the creek. There were white ladies and black ladies and foreign ladies too. Fat Ruth’s was the first in the Bottom to do such a thing, and that was fine by the cook. He said to each as she passed, “You looking every inch a peacock tonight.”

Another man stepped from the restaurant and concurred. “Like a springtime payday out here,” he said.

Al rapped his middle boy’s door, three quick.

Abe had heard someone coming on the stairs. He picked up the spike nail and put it back in his pocket.

When he opened, there stood his Daddy, sweat drops squeezing forth from the pores in his nose. Behind him was Jake, who smiled and pushed his way in and tried to make himself as tall as his younger brother by standing straight. He stuck his face in Abe’s. “Don’t forget whose room it was first,” he said. “Don’t forget who can whup you in a fair fight.”

Abe wouldn’t forget. After Goldie, it was Jake who knew him best.

Al closed the door behind him. “Do you play at Trent’s table?” he asked.

“Who’s tending bar?”

“You answer my question Abraham.” Al spoke loud and set his jaw. None of the boys would ever forget who could whup all three.

Abe said, “I played at his table and I won.”

Al shook his head and looked at his hands. He wanted to use them to choke his middle boy, but it would serve no end. Al had known it the first time he’d ever switched Abe, who was ten at the time and had been seen hopping a slow coal train. While Al swung the switch, the boy had whistled with his eyes shut, and he’d spat on the ground when it was done.

Choking the boy wouldn’t steer him clean. Al crossed his arms.

Abe thought his Daddy looked old then, and he thought Jake did too.

Jake had a pint bottle in his back pocket. He had a pencil behind one ear and a skinny cigar behind the other. He was supposed to be fixing the storeroom shelves.

“Who’s tending bar?” Abe asked again.

“Big Bill. He come over with me,” Jake said. He was dark-handsome like Abe, but his nose was bigger and his chin weaker.

Abe knew by the way his brother said “come over with me” that Jake had been at Fat Ruth’s again. He’d been lifting from the saloon’s money box for two years, just enough to dip his wick once a week. Abe said, “Bill’s not well.”

“He’s better now.” Jake put his thumb to a corner edge of peeling wallpaper. “Worry about your own health Abe,” he said. “Be dead soon enough you get in with Trent.” He walked to the closed wardrobe and knocked on it. “Never was well made, was it?”

“Goldie won’t like seeing her Daddy at the barback,” Abe said. “He’s ill.”

“Bill will be okay.” Al uncrossed his arms and breathed hard through his nose. He said, “Abraham, Henry Trent has nothing for you. You think he gives you everything, but he gives you nothing in the end.” He opened and closed his hands. “As he gives, he takes.”

There was a noise outside the door and the three of them turned their heads.

It was Sallie. She’d swung it open without knocking and looked at the men. She toted an unfamiliar baby girl on her hipbone. Behind her was Sam, the only Baach boy forever in need of sunlight. He was skinny as ever and fourteen years old.

“Stand up straight Samuel,” Al told him.

The boy did so and followed his mother inside.

“Shut the door,” Al told him.

Sallie said to leave it open. She looked at Abe when she spoke. “We’re not staying.”

The years had not been easy on Sallie, but they’d fortified her resolve. After Samuel’s birth in ’83, there was a still-born. A year after that, there was another, and for a time, Sallie only lay on her back in bed. She’d taken one basting spoon of chicken broth per night for two months. One day she came out of it and never looked back. The Baach boys did what she told them, and Goldie and Big Bill helped at Hood House when it was needed, but mostly Sallie ran the place, and she did so with considerable attention to cleanliness and well-kept books. In ’95, she took in the unwanted baby of a Tennessee girl working at Fat Ruth Malindy’s and named her Leila. With Goldie spelling her from time to time, Sallie attended that child’s every need, sleeping next to her crib up at the second house on the hill. At Christmastime in ’96, a wealthy friend of her father’s and his thin barren wife adopted Leila, and Sallie had nearly taken to her bed again. Instead she cried for a night and half a day. Then she stopped. “Sometimes, the eyes can’t keep from crying,” she’d told her boys. “They’re pushing out the poison.”

Now Sallie’s hair was mostly gray. She’d kept it long. She shook her head slow and said to Abe, “You look guilty.”

The unfamiliar baby tossed her little covered head and made a noise.

Sam tapped his foot on a floorboard by the bed. He suspected his brother of hiding money underneath.

They had all known that another motherless child was coming to Hood House to live because Sallie had proclaimed it and Goldie had backed her up. The child was born December 30th in a bed at Fat Ruth’s. Her mother had left before sunrise on New Year’s Day.

Abe regarded the baby and thought on how to answer his mother’s accusation of guilt. “I am guilty of making the kind of money that will build you another house, and another one after that. Anybody that wants to live on the hill can do it in—”

“I thought that maple baby carriage was in here,” Sallie said.

“Storeroom,” Al answered. “But steel brake is broken.” He looked at his watch and walked out the open door.

Jake pulled the half-spent cigar from behind his ear and lit it. He said, “Somebody’s got that carriage loaded with pickled egg jars.”

Sallie hadn’t looked away from Abe. She swung the baby to opposite hipbone. “Samuel!” Sallie called.

“Yes ma’am?” He’d sat down on Abe’s bed and was fixing to recline.

“Go unload the carriage and roll it to the street.”

“Yes ma’am.”

Jake opened the dresser drawer and looked at the newspaper lining. He slid his fingers underneath.

Abe turned, stepped to the dresser, and slammed it shut, Jake pulling clear just in time. “Don’t forget whose room it is now,” Abe told his brother.

The door closed, and they turned, and their mother was gone.

“You got the gold pieces?” Abe asked.

Jake produced a small burlap sack tied with twine.

Abe took it and tossed it on the bed. He retrieved his jacket from the wardrobe, stuck in one arm, and pulled the sleeve inside out. In the silk lining there was a long, buttoned sheath at the seam. He loaded into it, one by one, the little cedar pieces painted gold. They were hand-cut by Jake, just like the saloon’s poker chips. Abe rebuttoned, righted the sleeve and put the jacket back on.

Jake laughed. “Goldie sew that?”

“She is possessed of many talents.”

He opened a vest button and put a hand inside. There, in a seam in the lining, were four slick pockets where he customarily kept two of each bill, one to ten. He took out a five and handed it to Jake. “Just watch you don’t catch Cupid’s plague,” he told him.

Jake smiled. “Whatever you say highpockets.” He shook his head. He admired the insistent spirit with which his younger brother lived. He only hoped that Abe would stay alive long enough to tamp it down, and that tamping it down might buy him a few more years, and that those few years might carry him to the time in a man’s life when he quits carousing, when he’s content to read books again, like he’d done as a boy, and Jake and Abe and Sam might get old together, telling stories about how it is to go bald or to watch your shot-pouch sag to your knees.

“You got any of that Mingo shine?” Jake asked.

Abe shook his head no. “I’ve got to get downstairs.” He took a fresh deck from a stack on the dresser.

“You planning to play at Trent’s hotel?”

“Not tonight.”

“Tomorrow?”

“No.” Abe pulled on his shirt cuffs. “But Jake,” he said, “I might soon play there every day, and if I do, the money will come back here and up to Hood House both. You can have all the tools and timber you want.” He knew his brother was happiest when he built. “Frame another house on the hill, and down here a proper stage, new card room.”

Jake shook his head. His cigar was burnt out again. “Trent won’t ever give you that,” he said.

“Like hell he won’t.”

After they’d stepped from the bedroom, Abe locked the door again. There was hollering from the storeroom downstairs. They descended.

Sam had dropped a two-gallon jar of pickled eggs. Thick sharp wedges of curled glass sat dead against the cold soak. Brinewater marked the floor in a hundred-point burst. Sam pushed a broom at the eggs, and they rolled, soft and lopsided on the dirty floor, brine-red, some of them split yellow. Sallie had the baby in the emptied maple carriage. She used it like a battering ram to open the swinging door and depart. She didn’t look at any of her boys.

Abe told Sam not to worry. As long as there were chickens, there’d be eggs, and as long as there were eggs, people would pickle them with beets, and the world would be a proper place.

He swung through the door, arrived at the stage in three long strides, and leapt upon it to take his rightful place beside his queen. The men at the foot of the stage nodded to him and he bent to shake the hands of twenty or more, patting their shoulders with his free hand. The week prior, a track liner had told another man that his poker luck had swung high since he’d shaken the hand of the Keystone Kid. Word got around.

Goldie said, “Get them hats up swine!” She was fixing to scale and shoot another round of cards. She fanned them in her left hand and took a wide stance. The men before her held their hats high, low, and sideways too. Abe got out of the way. He watched her right arm coil slow above the deck. The men went silent and still. Goldie pinched the first and sprung hard her wrist and elbow. Her fingers, on the follow-through, spread open like honeysuckle. Then came the sound from inside the hat’s crown, sharp and dull and full and empty all at once.

Abe closed his eyes and listened to the next and the next and the next after that. It was a sound he could listen to all night.

When she’d finished, she bowed and Abe stepped forward again and said, “And men, when you fish in those pockets for tips, see if you don’t come upon another thing too.”

And they did come upon another thing. “I’ll be durn,” one said to the other as they brought forth quarter-sized cuts of wood painted gold. “How in the hell?” one man wondered aloud, and indeed it was a mystery how Abe had gotten the little gold tokens into all of those various workingmen’s pockets.

“Each of those gold tokens was hand-cut by my brother Jake, who is practicing to become the finest carpenter these parts have known,” Abe told them, “and each of them is good for one beer at the bar.” They mumbled approval. “Men, be sure to tip generously, and keep coming back to A. L. Baach & Sons for all your social needs!”

They spewed what earnings they could spare at the coal bucket and moved as a mass to the bar, where Al and Jake and Big Bill worked to pull, pour, and serve every man who saddled and showed his wooden gold. While he worked, Al glared across the barroom at his middle boy.

Goldie poured the coal bucket’s contents into a big empty cigar box she’d brought over from Fat Ruth’s, where, when business was good, gentlemen callers went through a large box a night.

“What’s the take?” Abe asked her.

“Above average.” She fastened the box shut and tucked it in her armpit. “I want to hear about your card game,” she said. He wore a look she couldn’t read. She winked at him. “I want to get out of this get up too.”

Abe told her he could help with that and that his take was likewise above average. “Let’s get to the storeroom,” he said. He looked to the bar, where the more ambitious men were finishing their free beers. “Just watch a minute,” Abe told Goldie. “See if my plan works.”

And it did. He’d calculated that the men, upon swilling their gold-token good fortune, would be of a mind to have another. He knew that those coming off their shift would’ve stayed only long enough to see Goldie before they went home, cleaned themselves, and set out to behold the Alhambra. But plans could be changed. Now the men set their dented pewter mugs on the bar top, wiped their mouths, and pulled out their watches. “I reckon I’ve got time for one more,” they said, and they fished once again for coins that would lead them where they wanted to go.

“See that?” Abe said. Then he checked his own watch. “Now let’s get to gettin.” He pushed Goldie ahead of him and kissed at her neck when they got to the swinging doors. “We got time for me to show you a thing or two.”

But in the black damp of the storeroom, it was her who showed him. They’d long since found a corner place, between the wall and the floor safe.

She pushed him against the cold back wall. She set the box of coins on the waist-high safe and put her hand to his trousers and worked the buttons on his fly. He picked her up and set her on the safe. The cigar box dropped and sounded a tambourine call. “Leave it,” she said. She tugged at his belt and pulled down his waistband, and when her fingernail cut the pale skin at his hip, he paid no mind. He took off her crown and let it drop. She raised her arms and he skinned the cat and tossed aside the gold feed-sack. Underneath, long-legged underwear was ill-fitted and easily kicked free. He lifted her, one hand under her arm and the other at her thigh. They slowed then and stopped breathing until she had taken ahold and guided him in and pressed herself as close as she could. And it was like that for a moment before they remembered to breathe, and his forearms burned from holding her while she rolled her hips, quickening all the time, toes gripped against the cold panel wall.

They sat together on the gold feed-sack afterwards, and Abe lit a match and showed her the contract. She kissed him. She was pleased at the sight of the long, looping numbers, but she did not say so. She did not say anything, for as quick as they’d brought pleasure, those same numbers struck in her a strong and sudden premonition that life, for a time, would be splendor, and then Abe would be gone.

He burned his thumb and tossed the match. He lit another and showed her a twenty.

She tapped her knuckle on the safe behind her. “What’s in this thing?” she asked him.

“Dust.”

There was a pickled egg at the floorboard within Goldie’s reach. It caught the match’s light and shone pink and smooth. She leaned and reached for it. She blew off the dirt and ate it.

When they stepped from the storeroom, the men had cleared out. Goldie took up a dustpan and headed for her Daddy, who was sweeping by the door.

Jake dunked mugs in one tub and rinsed them in the next. Beside the tubs was the stack of little gold pieces he’d cut. He had ideas on putting a hole at their middles or branding their faces with a B.

Al stood over his rosewood cash box behind the bar. He sorted dimes from nickels and quarters from halves. He bagged them accordingly. He licked his thumb and rifled the notes and put them in an envelope. The count was high for a Wednesday.

Abe came up behind his Daddy slow and silent. “How’d we do?” he asked.

Al nodded. He closed the cashbox and turned around. “I want to come and choke you when I see the men with the gold, but too busy.” He tapped his finger to his forehead. “Now I see your plan.”

It was the first time the two had smiled at each other in a year.

“How many normally leave after Goldie throws the cards?” Abe asked him.

“You are a smart boy Abraham.”

“How many?”

“Half?”

“At least. They want to get where they’re going.” In conversation on games of confidence, Abe talked near as fast as he thought. “How many walked out that door tonight?”

“I imagine five—”

“None.” Abe reconsidered. “Well, one. But only if we count the over-served boy who snuck back in after you’d tossed him.”

“And then I toss him again.”

“There you go.” Abe watched his Daddy laugh. He joined him. “Can’t count one that doesn’t drink and been tossed,” he said. “And I’ll bet some ordered another after, and another after that, all the while talkin to each other about coming back tomorrow.”

Al felt old next to his middle boy. Small, too, for though Abe was not as thick-ribbed as his Daddy, he was two inches taller. He patted Abe’s shoulder. “Remember, Abraham,” he said, “Even the smart boys can listen once in a while.” He tapped his forehead again. “Even the big boys can get hurt.”

Al had just turned and picked up the cashbox when the door opened. It knocked hard against the head of Bill Toothman’s push broom.

Rutherford stepped inside. Behind him was Taffy Reed, Rutherford’s errand boy and son of Faro Fred. Taffy was a year younger than Abe. He was well above average at the card table and had come by his moniker there. For a nickel, the young man would roll up a shirtsleeve, straighten his arm, take the elbow skin between his fingers, and pull it down, a stretch of flesh some five inches in length, highly reminiscent of the elastic properties of chocolate taffy.

“Evenin Baaches,” Rutherford said. He gave a foul look to Bill Toothman who was next to him, twisting the broom handle back into the head.

“Evening Rutherford,” Al said. He put down the cashbox and took note of Rutherford’s sidearm, which seemed to have grown longer somehow. He watched the little man spit tobacco juice on his floor though there was a spittoon to his left.

At the bar, Rutherford climbed on a stool and Taffy Reed stood.

“I’m going to walk Daddy over,” Goldie told Abe. She kissed his neck, whispered that she’d be back, and took hold of Big Bill’s arm. The sweeping was done. Al had given her an extra two dollars for her Daddy.

Jake dried the mugs and kept his back to their patrons.

“What can I get you Mr. Rutherford?” Abe asked.

“I’m not staying for a drink.” He reached in his jacket pocket. “I come to bring you a note from Mr. Trent.” He handed over the sealed envelope, Abraham Baach on its face.

Abe thanked him.

Rutherford ignored him and looked at Al. “Jew Baach,” he said, “your boy played some mighty strong hands today.”

“He is a smart boy.” Al wiped with his rag at a sticky spot beneath his wedding ring.

“That’s what they tell me,” Rutherford said. He regarded the strange oil painting tacked up on the wall, a wide crude depiction of a house on a mountain, a homemade job. Below it was a shelf with a half-empty pipe rack and a framed lithograph of Lincoln that stared back at patrons no matter their stool. “You all know Taffy Reed I’d imagine,” Rutherford said, motioning to his companion.

Each man nodded at Taffy, who nodded back.

Rutherford looked over his shoulder at the young man. “For all I know, you’re in here every payday Taffy,” he said. “Baach serves niggers and under eighteen both.” He laughed.

“All men are welcome in my saloon,” Al Baach told him, “but the patron must be eighteen for beer, twenty-one for spirits.”

“I’m only pullin your leg,” Rutherford said.

Taffy Reed scratched under his wool cap. He chewed on a toothpick he’d soaked overnight in a jar of homemade whiskey.

“Alhambra’s no-nigger policy won’t last,” Rutherford said. “Mark my words, inside a couple years, Trent will be letting em in like the rest of Keystone does—ain’t no other way when they come to be a majority.” He regarded his fingernails, which were in need of trimming.

Jake scooted the gold pieces off the counter into his open hand. He put them in his pocket.

“What you got there Jake Baach?” Rutherford asked.

“Nothin.”

“Somethin can’t be nothin,” Rutherford said. He stared down the Lincoln lithograph. “You got any pickled eggs?”

“No,” Jake said.

“How about just regular hardboiled.”

“Plumb out.”

Rutherford looked at the mantel clock under Abe Lincoln. Breakfast wasn’t too far off. Every morning of his life, Rutherford ate a half dozen hardboiled eggs. As of late he’d had a penchant for the pickled variety.

“I can put on some coffee,” Abe said.

Rutherford just sat. “Seems like your crowd here didn’t make it to the hotel’s big opening,” he said. “Or if they did, they came awful late.”

Nobody said a word.

Taffy Reed flipped his toothpick and bit down the fresh end.

“Look here,” Rutherford said, turning his attention once more to Al. “Word come down that you ain’t on the hook anymore for monthly payments.”

Al could scarcely believe his ears.

Rutherford looked at Abe and spat again on the floor. Then he smiled at Al. “But what’s say for old time’s sake you go on and give me one last handful.”

Al said he supposed he could do that.

Abe watched his Daddy turn and open the money bag. He whispered the numbers as he subtracted from his count.

Before they left, Rutherford told Abe, “I reckon I’ll be seeing more of you real soon.”

In Rutherford’s fist was the last of the consideration money he’d collect from any Baach. He muttered as he left. He had work to do. A young coke-yarder had passed out on the tracks and been cut in two. Rutherford would have to drain what was left from him, and affix him again in a singular piece, and pump him full of preservation juice. Or, if he was tired enough, and if he reckoned there was no kin to miss the boy, he’d wheelbarrow his two halves up Buzzard Branch to the old bootleg slope mine. He’d unlock the big square cover and dump the boy down. Either way, he had work to do before he could retire to his room at the Alhambra, where he would skim from the take like he always did and put a single dollar with the rest of his secret things, inside a locked trunk under his bed.

Jake watched Rutherford leave and said, “There is something wrong with that man.”

Al shook his head. “He likes to make believe he is powerful like his boss.”

“Well ain’t he?” Jake produced his tool chest from beneath the bar and poured himself a beer.

“He look like he is to you?” Abe said.

Al thought on acknowledging the cessation of collection. He wondered for a moment if his middle boy might indeed have found the way, if Trent might finally cut them in on the real money. But he was tired. He told them he was heading upstairs to bed. “Please don’t hammer tonight,” he told his oldest boy.

“Only cuts,” Jake said. He was building an arch and batten for the stage.

They watched their Daddy back through the swinging door with the money bags. “Goodnight boys,” he said.

They said it back in unison.

Jake finished off his beer, crossed the room, and set to work with a pencil in his teeth.

It was customary for Abe to watch his brother mark and cut. He’d done so for years, ordinarily while he counted his daily take or practiced his card manipulations. He gave Jake the nickname Knot, for Jake would stare at a two-by-four knothole for ten minutes. He would turn lengths of wood in his hand and he’d sniff at butt cuts, and in all those years of moments he rarely spoke a word. Abe found peace in his brother’s wood rituals. It was, for each of them, as if they’d found a quiet place, a place both together and alone.