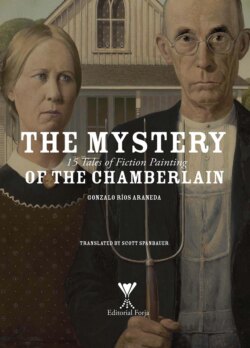

Читать книгу The Mystery of the Chamberlain - Gonzalo Ríos Araneda - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE INCIDENT

ОглавлениеLeonardo da Vinci

Mona Lisa, partial reproduction, 1503

From the first day of that month of March 1503, when the wife of Francesco del Giocondo settled herself in in front of all those musicians, a bit motley in the shadows and with their backs to the painter, you could sense an atmosphere of premonition in the hall. Three musicians and two singers arranged their instruments and looked over their scores, while a young man, whom the master Leonardo later on will call by the name Giacomo and, depending on his mood, Salaì, slipped away toward the back of the room —whose walls were covered with maroon-colored curtains— without ever taking his eyes off the woman seated on the posing bench.

The men tuned their instruments, two lutes and a small wooden clavichord; the first two, one plucked with the fingers and the other with a bone plectrum, to an attentive ear, produced, both of them, very different vibratos, but capable of harmonizing with the small apparatus’s low and high notes. Meanwhile, the singers, a man and a woman, looked over the madrigals meant to create the atmosphere the painter was looking forward to for the scene.

In a moment, and without anyone demanding it, the room fell silent. Through a side doorway, somewhat low, as it required Leonardo to bow his head a bit, the master made his entrance, and right away the place was left as if suspended in air.

The woman on the bench could barely conceal the impression the artist’s form produced in her. He was a man roughly 50 years of age who, in her opinion, carried them with elegance and dignity. Behind his thick beard, barely flecked with grey, one could discern the beautiful regularity of his facial features, whilst his gaze radiated an aura of deep sensuality. His face exuded a mysterious power and a perceptible self-dominion; perhaps even a talent for seducing others. He dressed with a simplicity that nevertheless revealed the quality of his clothing.

Giving little more than a wink by way of greeting, the painter looked at his model as would one inspect a harquebus before hanging it up in the armory. He walked around her and stepped away for a second, drawing in the air with his fingers and tightening an invisible string from the beautiful feminine head up to his left eye. Like a hawk’s, his pupil dilated until it filled with light.

She couldn’t help but feel a tingle of amazement and bewilderment: a large pair of searching eyes had begun to wander over her form, discerning the weight of every part of her body and connecting the surrounding lights with the empty spaces. Through no decision of her own, and as if by magic, she had become the center of a commotion drawing the attention of every one of those present in the room. It was then that, without a single word intervening, her gaze met the artist’s, and she couldn’t escape the burning flush that spread across her cheeks.

“My only aim is that you be happy here and in your beautiful and human prison,” was all that Leonardo spoke that first day, because he occupied himself with the scientific sketch of that lady who captivated him in some mysterious way. Armed with a piece of charcoal, he drew the outline of the woman’s bust and head on the poplar board he’d prepared, achieving the basic outlines with an astonishing speed. Such was his “sinisterity,” a word Salaì invented alluding to the painter’s left-handedness. Giacomo was quite inventive and keen that way and punctuated these events with loud guffaws. It was clear that he had developed a great ability for capturing the essence of the everyday, a virtue that he offered up to his master with an incurable mischievousness. Perhaps just because of all that did his protector appear so indulgent toward him. Standing behind the artist, the lad observed his master’s movements with an expression of banal self-complacency attributable only the pride of being his servant.

The following day, beneath Giacomo’s impertinent scrutiny, she realized that Leonardo’s gaze had fallen upon her hands, in response to which a strange itching took up residence in her navel. She felt naked when Leonardo, in an attempt to separate her from the world, removed the wedding ring from her left hand. It was then that a smile, rather old-fashioned, radiated from her face. From then onward, the painter appeared to regard her every gesture, every movement she made in that place, as sacred.

Nevertheless, a few days later that state of evanescent excitation was shattered by the inopportune behavior of Giacomo who, after giving his master an extended kiss on the cheek, turned to her, and under the pretext of straightening a pleat of her dress, seized her by the arm and sunk his heavy fingers into her flesh as if jealousy had taken over his soul. Annoyed, the Madonna had only just regained composure when the master, without a word, bent over her and rearranged her hands.

During the rest of the first week the beautiful model saw no more of the boy who had bothered her, but an unexpected circumstance caused a note of concern to lodge in her spirits: her husband, don Francesco, had arranged to stay in the studio longer than would be prudent. He hoped to keep an eye on the progress of a work toward which he had made a substantial advance and he persisted in this behavior until Leonardo began to manifest symptoms of displeasure. Confused and fearful, she contrived a way of suggesting to her husband that it was inadvisable to monitor the workshop too closely. To her distress the man attempted the same the same next day, but was unlucky enough that, when he tried to enter the studio, he met Giacomo coming the other way, leaving the room, and the master bolted the door behind him. “I don’t want that gentleman sticking his nose in here,” could be heard from the other side, which Giacomo, with a forced smile explained to the merchant as his master needing to concentrate excessively and that any suggestion could be directed through him. “Not to worry, don Francesco, all of your opinions will be duly considered by my master,” he told him.

Leonardo, impassive, continued in his work. Today, as ever, he arranged the woman’s hands. The Florentine’s left-hand fingers raised her right hand and put pressure on the heart line, oblivious to the current of sensuality that ran suddenly through the model’s body.

It was a calm morning, probably owing to the absence of the band of musicians that Leonardo himself had dismissed considering their mission completed. With a dose of guilt, she thought of her husband and those ideas that had been troubling her since she gave herself over to the other man’s dark powers, unable to avoid her pulse quickening as each session came to a close. When Leonardo announced that Gian Giacomo would escort her to the door, a feeling of dejection enveloped her that she didn’t know whether to attribute to the young man, or to her husband’s tantrums at home.

One night, Francesco threatened to confront the artist so that, once and for all, his money might impose the terms to which he believed he had a right. “I only see rocks all around,” he said, referring to the background of the portrait, still in outline form. “My wife doesn’t deserve that,” he complained in an effort to win his wife’s complicity. He thought that the costly attire he had acquired for her to model was reason enough to validate his point of view. However not only did this man object to the artist’s work, but he also insisted upon discovering illicit acts on the part of the painter and savaged his wife with unfounded suspicions, such as “the intense looks he lavishes upon you without modesty.” But he was careful not to confess to her that he writhed in jealousy when the other took her by the hands, because he was convinced that the old man touched her with lasciviousness.

As was to be expected, as the months and days progressed, the painter reduced his studio time, and the meetings were spaced further and further apart, because he had to attend to delicate obligations as the Duke’s engineer.

“My lord must attend the siege of Pisa,” said Giacomo to don Francesco. “He must provide important high engineering and architectural services by order of His Lordship the magnanimous Cesare Borgia.” He said it with such affected solemnity, that it aroused the wealthy man’s irritation. Worse, Leonardo was under pressure for other deliveries, such as that painting of the battle of Anghiari that his Lordship commissioned of him, with the aggravating factor that he had to submit said epic’s compositional perspective to the judgment of that overbearing and inscrutable signor Machiavelli. Now he has begun to paint in the woman’s absence, and only when that increasingly precious time is available to him. The other afternoon he warned that sessions would be suspended for a couple of weeks because he needed to be away from the city. He also told her that he would make an appointment with her only were it necessary. How distressing!

But Francesco del Giocondo was not at all pleased by this premeditated deviation from the signed contract, and he let it be known to the Florentine, because, he yelled out loud at Giacomo, he had rights and would not accept the artist’s capricious treatment of him; he demanded the painting be finished.

“Even though it regards signor Leonardo da Vinci, I will bring my complaint before the Duke,” the man shouted from the portico. “You have been deceiving me the whole time. I’m going to complain to his lordship the Duke,” the banker insisted, as if Giacomo didn’t exist. It was easy to hear him, because the door had remained half-open. “He tells me to wait ten days, then to wait ten more…, and it’s already been 10 months… when will it end!”

On the other side, Leonardo approached the door, closed it carefully and returned to his work.

Predictably, in no time the master flew into a rage and clarified to the gentleman that the contract did not authorize meddling in his work and that, by persisting in his demands, he would find himself obligated to cancel the agreement, along with the reimbursement of the gentleman’s compromised funds. Naturally, all of this, coming from Giacomo, caused the magnate to respond, through the same channel, with renewed threats to appeal to His Lordship.

Faced with such clear evidence of things wrapping up, the Florentine decided against going forward with the contract that tied him to Pietro Francesco Bartolomeo del Giocondo and sent Salaì to tell him so, while he prepared to leave the city of Florence, as he needed to return to Milan. He would return to the portrait as many times as were necessary and for as long as considered convenient, because for some time now the Madonna’s presence was no longer indispensable to him.

Lisa Gherardini never again returned to Leonardo’s workshop, and according to the news from the palace, she shut herself up in the connubial residence on the outskirts of Florence, where, for several days she refused to speak to anyone. It’s said that later, and for the rest of her life, she dedicated herself to her husband and to bringing up her considerable brood, with the sole desire of being a faithful wife and loving mother.

The last day the painter and his model saw each other, she was alone, standing like a virgin inquisitor beneath the doorway’s lintel, as if awaiting this moment like a wedding’s consummation. When he approached her, she allowed him to take her hands, while he bent and kissed the back of one. The woman, blushing and silent, let the same smile creep across her face that the master captured that second day in the workshop, months before. Immediately, guiding her gently by the waist, Leonardo brought her to the stairway that led outside; then Salaì ran to open the carriage door, beneath the watchful gaze of the coachman holding the reins of the steed that would take her home. Lisa settled into the seat and placed her hands in her lap, and when the coach began to move, she let her eyes close, as if trying to hold a long, secret restlessness in her memory.