Читать книгу Fire of Transformation - Gora Devi - Страница 12

New Encounters

ОглавлениеDelhi, 18 May 1972

I have started to travel around on my own without any fear or uneasiness. The other day, while waiting for a train in the railway station, I spread a piece of cotton on the platform like the Indians do and I sat down patiently to wait, using the time, as they do, to contemplate life and myself.

Railway stations are meeting places in India, joyful and familiar, and people talk to each other all the time. The Indian people regard me as a curiosity, they ask me where I come from, why I have come to India, what I am looking for. They are surprised that I have left the West, which in their minds is a paradise of material comforts, in order to come here and share their poverty. Some of them ask me if I am looking for mental peace, invite me into their homes, offer me food and shelter, all with a great sense of hospitality and humanity. In India to be hospitable is regarded as a sacred undertaking and people offer it with much warmth, their eyes gentle and full of love.

21 May 1972

I have been in Delhi for a few days and I feel comforted by the city. In old Delhi, in the Crown Hotel, I meet up with my friends again, Piero, Claudio, Shanti and some other people recently arrived from Italy. The hotel is on three floors, old and dirty, but rather grand in its way and from the terrace there's a commanding view of the railway terminus in the old part of the city. It's also the crossing place for numerous roads, the point of departure for numerous destinations, the location of many Hindu temples alongside Muslim mosques. It seems like the meeting place of different civilizations, India, Muslim countries, the West, China, and Tibet. Down on the streets there's a continual movement of people, rickshaws, horses, carriages, cows and cars, there seems no end to it all. Cows are regarded as holy and are shown great respect, so if they decide to cross the road the traffic comes to a standstill.

Many Westerners are camping out on the big terrace as well as occupying the small, hot, humid rooms where they keep the fans on all the time. As in Bombay, people smoke a lot and consume large quantities of fruit juices, tea and sweetmeats, taking numerous showers to fend off the heat. It's not a beautiful or a comfortable place, but it has a certain magical charm despite the dirt and chaos, not least because there are people here like me, searching for truth, ready to risk everything, to suffer, even to go so far as to lose themselves completely for the sake of this spiritual adventure.

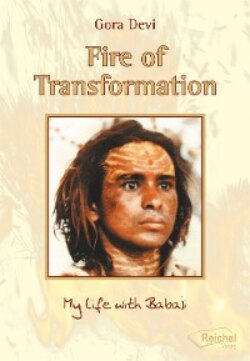

People come and go all the time, exchanging news, addresses, tricks for acquiring visas and how to survive in the jungle of the Indian city. Many of them have found Indian or Tibetan teachers and I also talk to them about Babaji and His beauty. I show them photographs of Him and as usual Shanti teases me saying I am only attracted to Him because He is young and beautiful, but it's not like that at all. Later on Shanti proposes that I visit one of his teachers with him, a Dr. Koshik, who is an ordinary man, married with children, but who is very wise and enlightened. He is a disciple of Krishnamurti, who doesn't favour the cult of the guru, or their rituals and mantras; I decide to go.

23 May 1972

Shanti continues to question me and asks what Babaji is teaching me. I have some difficulty in explaining it to him: about singing the mantra I say, and to wake up early in the morning to pray. Suddenly I recall what happened one day in Vrindavan. It was late in the morning, the temple had become empty and I realized that only Babaji and myself remained there, alone together. Immediately I panicked and felt extremely nervous. Then Babaji suddenly called me to sit with Him and we sat in silence. I was aware of my mind continuously active, frenetic, unable to make it stop, when Babaji told me to repeat Om Namah Shivaya. I tried, but even to repeat the mantra seemed impossible, artificial. Then all of a sudden my mind stopped for a few seconds and I experienced a strange calmness; Babaji gave me a broad smile and stood up. In that moment I sensed a silence inside me and realized the completeness of what Babaji had been teaching me. When I recounted what had happened to Shanti, I could see that he was impressed; he told me that, in effect, this experience of silence is what every master tries to impart.

It's incredibly hot and we spend almost all day in the hotel, only going out in the evenings. Living here is incredibly cheap and so we feel wealthy, going out to dine in different restaurants, travelling by taxi, buying clothes. But I am learning to understand many things, including for instance to accept the idea of poverty, which has a dignity over here. It's respected and even appreciated, because it's close to simplicity. In the Western world life is based on competition and arrogance, on the ego, and the poor have no place in society, neither do those who are old or infirm. In India there is room for everybody, including us crazy freaks. India has always had a capacity to accept different religions and traditions with a great deal of tolerance. The caste system is still present, it's true, but it also exists in the West, in a hidden way: the rich and the poor have an entirely different place and role in society. India is open to everybody, like a great mother and it is especially open to the spiritual pilgrim. It's like an ocean where many rivers merge from different civilizations. Here one feels so free that even poverty can be beautiful, colourful, joyful, and any strange behaviour is accepted.

Sonepat, 24 May 1972

I am at Sonepat with Shanti and a large group of his friends, in order to meet his teacher, Dr. Koshik. The doctor is a sweet man, full of love, with a blissful smile like the Buddha, wise and somewhat ironic. We are welcomed by his family with great simplicity and overwhelming hospitality. Like everywhere else in India I've always found that no matter how many guests there may be, they are treated with tremendous hospitality and offered somewhere to sit and an abundance of food.

For most of the time we sit with the doctor in a kind of meditation, talking from time to time, but very quietly and slowly. He expresses a keen interest in me, about my purpose for being in India so far from my home and has introduced me to his neighbours. When I sit with him, I feel immense peace and show him photographs of Babaji and tell him about the temple and my experiences there. I know from Shanti that he is a disciple of Krishnamurti and that he doesn't believe in the use of rituals, mantras and so on, only in self knowledge and self enquiry, but I feel a great respect from him. He talks about the importance of experiencing the spiritual in life and tells us that he attained a certain degree of awareness by simply sitting under a tree for some days, observing his own mind, seeking his own true self with eyes wide open, fully conscious.

After remaining with him for some time, I seem to have the same smile on my face that he has all of the time, a particularly quiet energy engulfing me; the doctor feeds us with Indian sweetmeats and showers us with love and affection.

Delhi, 26 May 1972

I've returned to Delhi again, before leaving for Rishikesh with Piero and Claudio to visit a great Tibetan lama. It feels right for me to know about other teachers and their diverse teachings, so as to deepen my understanding of Babaji and through this comparison come to value Him and His teachings even more.

Rishikesh, 27 May 1972

I have arrived in Rishikesh with Piero, Claudio and some other friends. On the train journey Rosa and I slept together on the same wooden bench.

Rishikesh is beautiful, green, and the water of the Ganges is clean, the river bordered by a wide beach of white sand. We are staying at the small ashram of Swami Prakash Bharti, surrounded by mango trees. The Indian people seem extremely pleased that we have come here and last night we cooked them a delicious feast of Italian rice with tomatoes.

The Swami has large, peaceful eyes, dark and warm. He plays a game with us: to each of us in turn he stares into our eyes to see who can look without blinking for the longest period of time, and he always wins. His eyes resemble the water of a tranquil lake.

The other day an extremely old sadhu arrived here, with exceptionally long hair knotted on his head, his body tall and thin, his skin brown. He walks particularly slowly on some strange wooden sandals and he seldom speaks. The Swami explained to us that he has been in a state of samadhi for one year, for all that time closed up in a cave, without consuming any food and even stopping his heart from beating and halting his breathing. Is that possible? Who knows if it's true, but the sadhu certainly seems like a being from another planet, he is extraordinarily gentle and detached from everything.

The other day Rosa was practising hatha yoga postures in the garden, completely naked. The Swami was embarrassed and laughed awkwardly, but the old sadhu continued watching her with complete indifference. The people here are extremely kind and they offer us food all the time as well as tea to drink, and they often smoke hashish. During the day we frequently take showers under the mango trees, trying to fend off the interminable heat and in the mornings we go to the river Ganges. The river is truly wonderful, the water pure and transparent, with a strong current.

The Swami is teaching me the Indian alphabet and some devotional songs. The other day he placed around my neck a rudraksha mala, a string of seeds from the tree dedicated to Lord Shiva. He told me that he is my guru but I don't feel this to be true. As yet I am not sure whether Babaji is my guru either, but I continually find myself thinking about Him and am surprised how difficult it is to take my eyes off the photograph of Him that I carry. There is a special beauty in His form, a purity that I have never encountered before, the energy of an angelic being.

In India, sadhus, the ascetics, are highly respected since they have dedicated their lives to God. People welcome them, give them food and hospitality. They often travel around the country having renounced a normal life, doing ascetic practices, like living on very little food or sleep, and meditating for long periods of time. Real sadhus are free spirits, beyond every rule and regulation, even if they follow their own spiritual discipline. They look, even physically, different from the rest of the Indian people, they have beautiful, supple bodies, often grow their hair very long and possess special eyes, warm and intense, with a particular light. They maintain a high degree of cleanliness, observing special rules of purity.

* * *