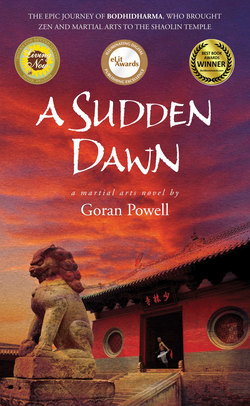

Читать книгу A Sudden Dawn - Goran Powell - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBodhidharma

The monk followed the jungle path beneath towering rose-wood and teak, past tamarind trees laden with ripe fruit, and banana trees with giant leaves reaching out to the morning sun. He stopped at a mango tree and picked the ripest offerings for later in the day before continuing into the dark heart of the jungle. Here the trees grew so close that they formed a dense canopy over the earth. Only the occasional ray of light found its way through the mesh of leaves, to dance on the jungle floor or illuminate one of the flowers that grew in that hot dark world. And when it did, the monk considered himself blessed to see such wonders.

He moved quickly, carrying few possessions: a blanket, a bowl, an iron pot, and a pair of old sandals that hung from his walking staff and swung in time with his step.

The jungle’s carpet of twigs and leaves felt good beneath his feet and the scent of spice trees and decaying undergrowth filled his nostrils like a rich perfume. Fallen fruit littered the jungle floor, shaken down by the wind and the monkeys that jumped and shrieked overhead. Now and again a new piece of fruit would fall, narrowly missing his head. He would scowl up at the treetops and shake his staff at the monkeys, ordering them to show some respect to The Buddha’s messenger. The monkeys would screech in reply and turn, showing him their tails in a gesture that spoke as clearly as any words.

By late morning the jungle had begun to thin. Soon he left the shade of the trees altogether and emerged into the blinding light of the open country. It was springtime in the kingdom of Pallava and the distant hills were a startling blue. The kurinji was in bloom. It was a good omen because the kurinji flowered only once in twelve years. The monk considered making a detour to sit among these rarest of flowers, but time was against him and he pressed on.

He picked up a country road that twisted through fields of wild flowers and sharp elephant-grass. Hoofprints in the dried mud told of oxen that had walked the same path some time before. He followed their plodding footsteps until the shadows disappeared and the sun was directly overhead. Then he laid down his staff in the shade of a purple jacaranda and prepared to drink tea and meditate.

He collected a pile of twigs, which burst into flame at the first spark of his flint, then set a pot of water to boil. While he waited, he laid out his ingredients: tea leaves hand picked from the wild bushes that grew in the region, sugar crystals, cardamom, and cinnamon bark. When the water boiled, he added the ingredients to the pot and set it aside to cool before taking a sip. The tea was just as he liked it: strong, sweet, and fragrant.

He closed his eyes and inhaled deeply, emptying his mind of all thought, fixing on nothing, until he was free to take in everything. The eye of his mind filled the sky and looked down on the green earth below before departing to explore the heavens. Moving freely in the farthest reaches of the cosmos, he occupied galaxies and worlds beyond description or knowledge, until his awareness filled the entire vast emptiness of the void. And then it was still. Neither moving nor seeking, unaware of self or other, it was one with all things, simply being.

By late afternoon, the monk had reached the banks of a slow-moving river. Reeds grew so tall that they obscured his view. He stepped among them, sweeping them aside until he saw what he was looking for, a rickety old jetty that stretched out into the brown water. He continued along the riverbank, enjoying the music of the reeds and the water, until a new melody reached his ears, the tinkling laughter of children.

A boy and girl were standing waist-deep in the water. The boy was young and bright eyed, with a ready smile. The girl was older, almost a woman. She was washing her brother’s hair and his dark curls glistened as she massaged coconut oil into his scalp. Her own hair had already been washed and combed, and hung long and straight down her slim back. She bowed to the monk and prodded her little brother to do the same.

“Greetings Master,” she called.

“Greetings, child.”

The boy bowed too, but there was mischief in his eyes. “Master, I have a question,” he shouted.

“Then ask it,” the monk said.

“Why don’t you wear your sandals?”

The girl prodded her brother angrily. It was bad karma to poke fun at monks, but this monk answered good-naturedly. “I like to feel the earth beneath my feet.”

“Then why carry them at all?” the boy asked, ignoring his sister’s efforts to silence him.

“Sometimes the ground is covered in sharp stones or thorns. Then I wear them.”

“If I had sandals, I would wear them all the time,” the boy said.

“Then your feet would grow soft,” the monk laughed, “and you would be afraid to feel the earth against your skin. And that would be a sad day because you would forget how good it feels.”

The boy was about to say more, but his sister pushed his head under the water and rubbed his hair vigorously. The monk chuckled to himself as he continued on his way to the jetty.

The old ferryman sat in his usual place, watching the river go by, as he had for so many years. A tremor in the jetty’s ancient beams told of a new passenger approaching. The old man did not turn to see who it was, preferring instead to try and guess from the footsteps. These were unusual, and for a moment he could not place them. They were not the steps of one of his regular passengers, of that he was certain. The tread was light and balanced, yet the jetty swayed under a considerable weight. He could recall such an effect only once before, when he had rowed a tall young monk across the water.

“Sardili!” he said, turning with a smile.

The figure on the jetty was not the young monk he remembered. A tangle of black hair fell onto immense shoulders. A thick beard hung down over a threadbare black robe. Worn leather sandals swung from the end of a gnarled walking staff. The stranger would have been a fearsome sight, were it not for the eyes that twinkled with mischief and laughter.

“Is that you, Sardili?” the old ferryman asked, shielding his eyes from the sun.

“Yes, my friend,” came the answer.

“I hardly recognized you,” the ferryman said with a frown, “Whatever happened to that clean-cut young man who passed this way before?”

The monk grinned and spread his hands. “He has been wandering.”

“Wandering? That doesn’t sound like him. He was such an earnest young fellow when I met him—so full of purpose. Did he lose his purpose?”

“On the contrary. I think he found it.”

“In Prajnatara’s temple?”

“Yes.”

“Well I’m pleased to hear it,” the old man said, slipping into his boat. “Come, climb in. We can talk as we cross.”

Sardili obeyed and the old ferryman began to row, his strong, steady strokes belying his advanced years and the skeletal thinness of his body.

“You’re visiting Prajnatara again?” he asked.

His passenger nodded.

“I’m sure he will be delighted to see you, if he recognizes you, that is, Sardili.”

Sardili smiled. No one had called him by that name for a long time.

“You have a new name?” the old man asked, as if reading his thoughts.

“I do,” he smiled.

“Tell me.”

“I have been given the name Bodhidharma.”

“Bodhidharma?” the old man chuckled to himself. “Well well, to be called ‘Teacher of Enlightenment’ that is quite an honor.”

“And quite a burden.”

“Perhaps, but Prajnatara is no fool. If he gave you such a name, you must deserve it. I will call you by that name from now on, Bodhidharma.” Then the old man saw the sadness in the younger man’s eyes and his tone softened. “Go and see Prajnatara again. He will help you, like he did before.”

Bodhidharma put his fingers in the warm brown water, then raised his hand and watched the golden droplets return to the river from his fingertips. “I should have visited him long ago,” he said softly.

“They say that to enlighten someone can take countless lifetimes, or a single moment,” the ferryman smiled, “so what’s your hurry?”

“You were a monk yourself?” Bodhidharma asked.

“I have been many things in my life,” the ferryman answered, steering the boat expertly to the shore and securing it against the blackened timbers of the jetty.

Bodhidharma stepped ashore. “What do I owe you?”

“Nothing,” the ferryman said with a wave of his hand.

“You said that last time you rowed me across.”

“Do you think I want bad karma by taking money from a penniless monk?” the ferryman asked testily.

“You don’t care about karma,” Bodhidharma said, looking down from the jetty, “I have never seen anyone as happy as you are here on this river. You would row the whole world across for free if you didn’t need to eat.”

“We all need to eat,” the old man said with sad smile.

“I guess we do,” Bodhidharma said, bending to grip the old man’s hand in silent thanks before entering the waiting jungle.

A parrot screeched a greeting and he returned its call without breaking stride. His thoughts were on the message he had received from Prajnatara and his fingers closed on the paper that he had kept in the folds of his robe. The hastily scribbled note had requested his presence at the temple. The tone had been casual and friendly, but Prajnatara never did anything without reason, and as Bodhidharma made his way to the little master’s temple, he wondered, not for the first time, what that reason might be.

Yulong Fort, China

Kuang’s breath came out in strangled gasps. Snot hung from his nose and a rich, thick phlegm gathered in his throat. He wanted to stop and hawk it up but that would mean giving up his slender lead over the other runners, and that lead was too precious. Corporal Chen was waiting for him at the top of the hill. By the time he reached him, Kuang’s thighs felt fit to burst, but he was still first and hoped for a word of praise from the corporal.

“Too slow, hurry up,” the corporal snarled, pushing him on down the shingle slope.

Two more soldiers were close behind. Kuang lengthened his stride to get away from them and fought the urge to look behind. It would only slow him down. The crunch of their footsteps told him they were only a few paces back. The temptation was too strong. Unable to resist, he stole a glance behind. They looked as tired as he was. It was good to know.

He reached a deserted farm building and scrambled over the outer wall. Earlier he had vaulted the same wall in a single leap, but this was his second lap of the training ground and this time he was forced to grit his teeth and haul himself up slowly. He lay across the top of the wall for a moment, wondering breathlessly how much longer he could keep up his furious pace.

The next two runners began to help one another to climb the wall. He despised them. He did not need help. He would be first, the best, the only one to get round the course unaided. He jumped down and set off again through thick mud that sucked at his feet, sapping his strength with each step. A pool of black water came into view. The stench pierced his nostrils. The place had once been a cesspit. More recently it had been allowed to fill with rainwater and Corporal Chen had thrown in rocks and tree branches to make it more difficult to cross.

Kuang jumped in up to his waist and felt his feet sink into the sludge. By the time he had reached the center of the pool, the water was at his chest and the stench had become unbearable. The first time he had crossed, he had succeeded in holding his breath, but this time he was too tired. He took a gulp of the foul air and retched. Nothing came up except a streak of yellow bile. He had not eaten for hours.

Corporal Chen was waiting on the far side of the pool. Kuang could see him beckoning and hear the insults ringing out across the water: he was too slow, too lazy, a disgrace to his parents, his ancestors, and all the soldiers who had served in the imperial Chinese army throughout the ages.

Was it true, he wondered? He was trying his best, like most of the others in his troop. They had not asked to join the army. They were not the elite cavalry that was winning glorious victories against the barbarians on the steppes. They were conscripts, little more than boys, stationed in a remote fort on the border with Tibet, a thousand li from civilization. A thousand li from home.

Corporal Chen was still shouting insults in his ear as he dragged himself from the water and stumbled along the gravel path to the remains of an old barn. The building had burned down years ago, leaving only crumbling outer walls and blackened timbers of the roof. He scaled the wall and climbed the first roof strut, ignoring the splinters that dug deeply into his hands. By the time he had reached the main crossbeam, the two soldiers behind him were at the wall. From their grunts and groans, he could tell they were suffering too, and smiled grimly to himself. They would not catch him. Not today.

He was near the end of the crossbeam when he noticed four dark shapes passing beneath him, four soldiers, crawling on their hands and knees to avoid being seen by Corporal Chen.

“Hey, you’re cheating!” he yelled, searching frantically for Corporal Chen, but the corporal was nowhere to be seen.

He jumped down and chased after the four who had stolen his lead. He saw them by a pile of logs at the bottom a grassy slope. The soldiers hefted a log onto their shoulders and set off up the hill. He grabbed a log of his own and hurried after them, his curses lost in his deep gasps for air. Soon he began to catch the last of the four. When he was close enough, he drove his log into the soldier’s back, sending him sprawling. The soldier lay in the grass, too weary to get up, his log rolling down the hill.

“You’ll pay for that, Kuang,” he snarled.

Kuang ignored him and hurried after the next man, who he recognized as Tsun. Tsun was big and powerful. During his short time in the barracks, he had already begun to intimidate the weaker conscripts. Kuang had kept out of Tsun’s way, but he now was too angry to care and jammed his log into Tsun’s knee.

Tsun stumbled and dropped his log with a curse but recovered instantly, spun around and smashed his fist into Kuang’s face. Kuang fell. His log landed on top of him. The punch had caught him on the nose and his vision misted over. He struggled to get to his feet, but was dazed by the punch. Tsun kicked him hard in the ribs. He rolled away, hoping to make some distance and let his head clear, but Tsun was too quick and pinned him on his back against the hillside. He saw Tsun’s black outline against the white sky, his fist pulled back for the first of many punches.

They never came.

Corporal Chen wrapped Tsun’s arm expertly behind his back and dragged him off. “Plenty of time for that later,” he said grimly, shoving Tsun away to fetch his log. Then he turned to Kuang. “I saw what you did, Kuang. Do fifty push-ups here and another lap of the course. Then rejoin us at the bottom of the hill.”

Kuang was about to protest, but the look on the corporal’s face changed his mind. He turned on his front to begin his push-ups. He was exhausted, and after five, his arms began to tremble. He gritted his teeth and continued to ten. Corporal Chen stood over him, waiting for him to stop or rest. “Why were you cheating, Kuang? It brings you no reward. I see everything you do. You have only disgraced yourself and dishonored your parents, your ancestors …” The corporal continued, but his words faded into the distance as Kuang slipped away to a place where nothing could reach him. He was too proud to stop or rest, and with the corporal standing over him, he would do all the push-ups. At any other time, fifty would be easy, but now, with his strength gone, he knew the pain would be immense. The only way to get through it would be to take his mind somewhere far away.

He lowered himself to do another push up. A blade of the coarse mountain grass pricked his forehead. He turned to the side, but as he lowered himself again, it tickled his cheek. It reminded him of a place and a childhood he had left behind, and all but forgotten. He followed the memory until it led him to another hillside far from the barren wilderness of Yulong Fort. He was back in the rolling green landscape of his homeland in Hubei. His friends were there, at the top of the hill, beckoning to him. He set off up the slope to meet them, but as he did, they turned and ran away. He could no longer see them, but he could hear their laughter on the wind. He ran hard to reach the brow of the hill and see where they had gone. He pushed harder, counting each step up the slope: twenty-seven, twenty-eight, twenty-nine … he was on high ground and the wind roared in his ears … thirty-two, thirty-three, thirty-four … The sun appeared over the brow of the hill and shone so brightly that he couldn’t see. Still he pushed on … forty-five, forty-six, forty-seven. Time slowed. His counting slowed, almost to a stop, but not quite. Forty-eight. His nostrils were filled with the smell of the grass, a scent so powerful it cut off his breath. Forty-nine. His eyes were screwed shut against the sun and he was running blind. He was almost there.

Fifty. He had reached the summit.

His vision returned slowly. He rolled onto his back and stared up at the white sky, then sat up and looked for Corporal Chen. The corporal had gone, and only his voice could be heard in the distance, cursing the other soldiers. Kuang rose and walked up the hill slowly, his arms limp by his sides. When he reached the top he realized something was missing. He had left his log behind. If Corporal Chen saw him without it, he would only add to his punishment. He went back to retrieve it.

When he reached the top again, he saw the others had finished the course and the corporal had marked out a square on the ground. The soldiers had removed their tunics and were wrapping their hands in rough strips of sackcloth. He made his way down the hill to join them, wondering what was happening. When he arrived Corporal Chen yelled at him furiously. “What are you doing here, Kuang? Go round the course again like I told you. I’ll be watching you. Move!”

Some of the soldiers jeered as he went past. They hated him. He knew that. He had made no effort to fit in. He had always tried to be better than the rest, and they despised him for that. He did not care. In his heart, he knew he would leave them all behind one day. He would become a great soldier. This was just a test that had to be endured.

A different voice cut through the jeers. “Keep going, Kuang.” It was Huo, who had the bunk above his own in the barracks, “I saw who cheated.”

Kuang gave Huo a small nod of thanks before setting off around the course once more.

“The rules are very simple,” Corporal Chen told the gathered soldiers. “No biting. No gouging. No attacks to the groin. China needs her soldiers to produce more little soldiers.” He smiled, but no one shared his grim humor. “You can punch, kick, and wrestle. You win when your opponent is knocked out or submits. You stop only when I say. There are no other rules.” He scanned the pale faces waiting around the makeshift square. “Wan and Lei, you are first.”

The two fighters stepped into the square and circled each other warily.

“Hurry up!” he bellowed.

They charged at one another, flailing wildly, neither in control, until a wild punch from Wan connected with Lei’s chin. Lei’s legs buckled and his punches grew weaker. Wan sensed victory and landed another hard punch on his opponent’s nose. Bright streaks of red splashed Lei’s chest. He doubled over, shielding his face with his arms.

Wan looked to Corporal Chen, hoping he had done enough to win, but the corporal stared at him impassively. Wan shrugged and drove his knee toward Lei’s head to finish him. Lei moved his arm at the last moment and Wan’s knee connected with an elbow instead. He gasped in pain and held his knee tightly. Still dazed, Lei rose from his crouch to see what was happening. Wan could not afford to let Lei recover. Ignoring the agony in his knee, he rushed forward, grabbed Lei behind the head, and pulled him onto his left knee. This time the blow connected hard and Lei crumpled to the ground with no more than a sigh.

Kuang had been watching from the top of the hill. He had done a little wrestling at the training camp in his hometown, but this was far more serious, and he was already exhausted. Whatever happened, he knew he was going to get hurt. He made his way around the course slowly, hoping to regain a little energy before having to fight. Corporal Chen’s voice could be heard barking orders at the soldiers, and the dull thudding blows of the fights echoed around the stony training ground.

By the time he rejoined the rest, the other soldiers had recovered their energy. Some were limbering up and stretching in preparation for their turn in Corporal Chen’s brutal matches, while others stood nervously waiting their turn. He collapsed beside them, hoping to rest. His hopes were quickly dashed when the corporal ordered him into the square, scanning the others for a suitable opponent. Even before the name was called out, Kuang knew who it would be.

“Lung!”

Lung was easily the biggest soldier in the garrison, a farm laborer from Hunan, and hugely powerful. Though not vicious by nature, Lung had the look of a seasoned brawler, and Kuang prepared for the worst.

They stepped into the square and Kuang’s eyes locked onto Lung’s for the first time. The small, round eyes were impossible to read, but he knew he could expect no mercy. He stayed at the edge of the square and fiddled with his hand-wrapping, waiting for a little freshness to return to his limbs. Lung figured out what he was doing and crossed the square with a roar, launching a barrage of punches at his head. He slipped to the side and struck at Lung, but the bigger man’s power drove him back. He stumbled and covered his head with his hands. Heavy punches smashed his arms and shoulders. He threw two more punches of his own and felt his fists make contact with Lung’s face, but Lung was unstoppable.

He skirted the edge of the square, hoping for a moment’s respite, but Lung was on him, catching him with a hard punch in the stomach that doubled him over. Lung smashed a knee into his body. Ignoring the pain, Kuang threw his arms around Lung’s legs to tackle him. Lung sprawled, throwing his legs behind and out of reach. His great weight bore down on Kuang’s back and he pounded vicious punches into his sides. Kuang drove forward to get a better grip on Lung’s legs, but Lung was too strong. Something had to change.

He dropped to his knees and twisted suddenly. Lung lost his grip for a moment, but regained control by falling on top of him. Now he was trapped beneath Lung’s bulk. He pushed and struck out with his elbow, catching Lung in the face, stunning him for a second. It was the chance he needed to squirm out. He stood and aimed a kick at Lung’s head, but tiredness had made him slow. Lung caught his leg and threw him to the ground, landing squarely on top of him and driving the air from his body. Now he was pinned securely, and Lung began to strike at his head with the base of his fist.

He turned away in desperation. It was a mistake. He had given Lung his back. Lung’s massive arms wrapped around his neck and drew a strangle hold in tight. He heard a roaring in his ears, felt the prickling redness behind his eyes. The world was closing to a small dot. With the last of his strength, he stood up with Lung on his back before blacking out.

When he woke, the pressure was gone. For a moment, he thought the fight was over and he had been carried to the side. But then he saw the eyes of the other soldiers on him and saw he was still in the square. Lung was beneath him. The throbbing on the back of his skull told him what had happened. His head had flown back when they had fallen and struck Lung hard in the face.

He spun and found himself on top for the first time. Lung’s nose was broken. Blood was running into his eyes from a deep gash and his hands were rubbing frantically at his eyes. Kuang felt a stab of pity for the big man. It lasted for just a moment—the fight was not over yet—Lung was a formidable opponent and could recover in an instant. He stood over him and raised his foot to stamp on Lung’s head. Corporal Chen stepped forward but Kuang was beyond waiting for the order to stop. He dropped to one knee and began punching steadily, until he felt two soldiers dragging him off his beaten opponent.

He stood with his hands on his knees, gulping in deep lungfuls of the thin mountain air, grateful for the respite, but his ordeal was not over. Corporal Chen nodded to Tsun, who was ready and waiting with his hands wrapped. Tsun rushed at him. Kuang raised his hands in futile defense. A huge punch found its way past his guard and caught him on the temple. He crashed to the ground. Then Tsun was standing over him, kicking at his head and ribs. He curled into a ball to protect himself and rolled away, scrambling to get to his feet. Tsun followed and kicked at his head, clipping him on the jaw. He fell again, badly dazed. Tsun pinned him on his back and straddled his chest. There was no escape. Vicious punches began to fall. He fought to push Tsun off, but Tsun’s weight was planted firmly on his chest. He parried Tsun’s punches and moved to prevent them from connecting hard. He struck back, but from his position on his back his punches had no effect. Tsun gripped his wrists and pinned his hands to his chest, then moved forward to sit on them and finish him off. As Tsun shifted his weight, Kuang bucked hard with one huge final effort. It was enough to lift Tsun a fraction and he slipped out between Tsun’s legs.

Tsun spun and seized him. Kuang felt a knee smash his ribs. The stunning pain made him feel faint. He threw his arms desperately around one of Tsun’s legs, but was too weak to take him down. Tsun resisted easily and struck at his head with hard punches. Too dazed to think any more, Kuang clung on grimly as Tsun punched him. All sense of time left him. After what seemed like an age, the blows became lighter. Tsun was still striking him—now he was using his palms instead of his fists. The blows registered faintly, somewhere in the distance. He guessed Tsun’s hands were too damaged to hit hard and he clung to Tsun’s thigh with a satisfied grin.

At last Corporal Chen sent two soldiers to pry him off. They dragged him from the square and laid him on his back, staring up at the empty sky. He did not move. His eyes closed and he drifted into a dreamless sleep.

Some time later, he did not know how long, he was dimly aware of more matches going on nearby. Then the sounds faded and he heard nothing. When he woke again, the sky was grey and the air cold. He began to shiver uncontrollably. Each new breath sent a stab of pain through his side. His head was pounding. His lips were swollen and there was a metallic taste on his tongue. He tried to stand but a searing pain ripped through his body and he fell back, groaning.

He considered calling for help, but his pride prevented him. He closed his eyes and waited, wondering if he would get back to the barracks before nightfall. Eventually he heard the crunch of footsteps on the shingle track. He tried to sit up and see who was coming. It was too painful. Instead, he raised his head, breathing hard with the effort. The approaching figure was nothing more than a silhouette in half-light. He laid his head back, exhausted, and waited. Finally a head appeared above him, but he could not make out the face against the darkening sky.

The Temple in the Jungle

Bodhidharma followed the narrow jungle path until he saw the fork in the river. The temple was near. Soon it came into view, its pale stonework gleaming in the mottled sunlight between the trees. A lone figure was working in the gardens and he recognized the slight frame at once. It was Prajnatara, tending the flowers. He called out a greeting and Prajnatara turned, shading his eyes from the sun. At the sight of his old student, the little master let out a cheer and hurried through the the trees, beaming with delight.

“Bodhidharma! I knew you would come. Did you get my message? Of course you did, you’re here, aren’t you? Well, well, let me look at you. You look …” Prajnatara paused, looking him up and down disapprovingly, “… quite different from the last time I saw you. Heavens, yes. It’s understandable. You have been on the road a long time and traveled a great distance to be here. I heard you have been wandering all over India. But listen to me chattering on like an old fool and keeping you standing out here in this dreadful heat! Come inside, my dear Bodhidharma. Come into the shade and cool off. You must be tired, hungry, thirsty?”

Prajnatara led him to his private chamber and rang a bell. A novice monk appeared and Prajnatara ordered refreshments for his special guest. “It’s so good to see you again,” he continued breathlessly, “I hardly recognized you after all this time. I see you no longer wear the orange robe of the order. And you certainly have a lot more hair …”

Bodhidharma shrugged apologetically.

“Well never mind, it’s of no real concern how a master dresses, and besides, you always were a bit of a special case. I remember the day you first appeared at our temple, how you showed us your wrestling skills. What a time that was! The young monks still talk about it today. Brother Jaina still reckons you’re the finest wrestler he’s ever come across.”

“How is Brother Jaina?” Bodhidharma asked, taken aback by the master’s overwhelming warmth.

“Oh, he is fine, and looking forward to seeing you, but all in good time, all in good time. First we must talk; or rather, you must wash, and eat, and then we can talk. Where is that boy?” He grumbled. Just then the novice appeared with a basin of water for their guest and Bodhidharma washed his hands and bathed his tired feet.

“I see you still wear your sandals on your staff,” Prajnatara said, handing him a vial of warm oil to massage into his feet.

“I’m saving them for a special occasion,” Bodhidharma said with a grin.

“Then keep them nice and clean,” Prajnatara said.

Bodhidharma raised an eyebrow inquisitively, but Prajnatara changed the subject quickly. “You look as strong and fit as ever. Even bigger than before if I’m not mistaken, and all muscle by the look of it. You still exercise?”

“Every day,” Bodhidharma answered.

“Splendid! I’m delighted to hear it. Fitness is very important, a lot more important than people realize.”

The novice reappeared with refreshments and Prajnatara had him set the tray down before his guest.

“Please have some first,” Bodhidharma insisted. Prajnatara was about to decline, but knowing his former student would not eat until he had taken something first, he helped himself to a small handful of rice, leaving the rest untouched.

“When I got your message …” Bodhidharma began, but Prajnatara held up his hand to silence him. “First eat,” he ordered.

Bodhidharma was hungry. He obeyed. The food was simple but tasty, just as he remembered it. He lifted a handful of rice and vegetables in his fingers and nodded his appreciation, his mouth too full to speak.

“We have a new cook,” Prajnatara smiled. “I have been instructing him personally. Now I think he’s even better than the old one.”

Bodhidharma ate quickly, sensing Prajnatara’s eagerness to talk. He also sensed it was a matter of some importance, despite Prajnatara’s attempt at small talk. As soon as he had finished, Prajnatara leaned forward and squeezed Bodhidharma’s arm affectionately. “Forgive me for coming to the point so quickly. I asked you here because I have a very important request to make of you.”

“There is nothing to forgive, Master,” Bodhidharma said, “I should be the one apologizing, not you. I should have visited long ago. I have been remiss. And whatever request you have, consider it done.”

“It is kind of you to be so understanding,” Prajnatara said, “but please hear me out before agreeing to anything.”

Bodhidharma was about to protest but something in his former master’s face made him sit back in silence and let him speak.

Prajnatara waited, seemingly unsure how to begin.

Bodhidharma could feel the little master testing different opening lines in his head, and he wondered what sort of request could cause Prajnatara to hesitate so. All at once the answer seemed to come to Prajnatara and he spoke breathlessly, as if relating the latest temple gossip to an old friend. “Recently I have been in correspondence with The Venerable Ananda, you know who he is, of course...”

Bodhidharma nodded slowly. “Of course, The Venerable Ananda is the Buddhist patriarch, the living embodiment of Buddha on Earth. Every Buddhist knows this.”

“Quite so,” Prajnatara said. “He is also a wonderful man. He was my master when I was young. I studied with him for many years in Nalanda. It was Ananda who enlightened me and showed me The Way. Now he is the patriarch and Grandmaster of Nalanda, and no monk has ever been more deserving of such a title. Since taking up that position, Ananda has worked tirelessly to ensure the transmission of the lamp.”

“The lamp?” Bodhidharma asked, determined to follow Prajnatara’s rambling speech.

“Yes, the transmission of The Buddha’s teachings! Once the flame of enlightenment has been lit, it must never be allowed to go out. Ananda’s efforts have been rewarded. Already the teachings have spread far beyond the five kingdoms of India—west into Persia, north into Central Asia, and east into China, where they are proving to be immensely popular. Recently we learned that the emperor of China himself is an avid follower of Buddhism.”

“That is encouraging news,” Bodhidharma said.

“It is excellent news. Excellent news. The Venerable Ananda has made it his life’s work to ensure people around the world are not denied the perfection of The Buddha’s teachings.

“He must be very happy,” Bodhidharma said.

“He is, but in his most recent correspondence he also intimated that he is gravely concerned.” Prajnatara paused, his brow knotted in a frown. “He writes of visions that appear to him with great regularity and clarity. They tell him that the future of The Way lies in the East, in China. The importance of bringing the teachings to the Chinese people cannot be overstated.”

“And this concerns him, you say?” Bodhidharma said, hoping to steer the little master toward the point of the conversation.

“Yes, most gravely, because China is vast, Bodhidharma! It stretches from the Himalayas in the west to the eastern Ocean, from the tropical jungles in the south to the frozen steppes of the north; and the population outnumbers all the five kingdoms of India put together. The journey to China is long and perilous. Only a handful of teachers are prepared to make it, or capable of enduring the hardships along the way.”

“I see.”

“I’m glad you appreciate the situation,” Prajnatara said solemnly.

A brief silence followed. It seemed Prajnatara was waiting for a reply.

“These are very important matters,” Bodhidharma offered, wondering what the master was expecting to hear.

“Vitally important! They are the key to the very future of The Way. So what do you say, my dear Bodhidharma?” Prajnatara demanded, the first signs of exasperation creeping into his voice.

“What do I say about what?” Bodhidharma asked, more bewildered than ever.

“About what we have been discussing …”

“I’m sorry Master, I have no idea what you’re talking about,” Bodhidharma said with a frown.

“About going there, of course.”

“Going where?”

“Oh, by the Buddha’s bones!” Prajnatara shouted. “To China, where else?”

Bodhidharma stared into his eyes and saw that he was serious. He let out a roar of laughter that shattered the silence. “You want to send me to China?” he asked, his body still shaking with mirth.

“That was what I had in mind,” Prajnatara said coolly, “and I don’t consider it a laughing matter.”

“Oh please forgive me Master,” Bodhidharma begged, wiping the tears of laughter from his eyes, “and please don’t think me rude. I’m flattered, really I am. I’m only laughing at the irony of it all, because, well, I haven’t told you yet, but I am a hopeless teacher. In the five years that I’ve been away, I’ve achieved nothing. I’m ashamed to say I have no disciples, not even a single student. The longest anyone has stayed with me has been six weeks, and this is teaching Indians, my own countrymen, people who speak the same language as me. So you see, I couldn’t possibly go to China and enlighten the Chinese. It would be a wasted journey.”

“I see,” Prajnatara said slowly.

“I’m the last person on earth you should want to send,” Bodhidharma said with a apologetic shrug.

Prajnatara sat quietly for a while, considering his words carefully before speaking. “Why do you think you failed, Bodhidharma?”

“My methods don’t work.”

“And what methods are those?” Prajnatara probed.

“Pointing directly to reality.”

“That is a very ambitious method, as I think I told you before.”

“You did Master, and I must admit you were right. But you know my thoughts on the matter. I don’t believe in debating scriptures and following rituals. For me it’s just so many empty words and empty practices. I would be a hypocrite if I started doing all that now. I hope you understand.”

“I understand more than you think,” Prajnatara reassured him. “You see The Way clearly Bodhidharma, but you don’t see how to illuminate it, yet. That is another skill you must learn.”

“You think I should teach scriptures and follow rituals?”

“I think students need something to grasp. You can’t simply snap your fingers and set them free. Things are never that easy, not for a teacher nor for a student.”

“Maybe you’re right,” Bodhidharma conceded. “I seem to be getting nowhere by trying to take a shorter path.”

“There is no shorter path. There is only the path. Each person must be allowed to tread it in their own time.”

Bodhidharma nodded glumly, “I guess you are right, as usual.”

“It’s never easy to break the spell of desire,” Prajnatara said. “Don’t be too hard on yourself. Remember how long you yourself toiled under the yoke of delusion before you saw the truth.”

“I remember all too well,” Bodhidharma said with a bitter smile.

“Try to be a bit more patient, with yourself and your students. I imagine you drive them quite hard.”

Bodhidharma stared at the floor without comment.

“Brother Jaina tells me you’re renowned all over Pallava,” Prajnatara continued, “The villagers call you the warrior monk. I think they’re perhaps a little afraid of you.”

“What are they afraid of? They have nothing to fear,” Bodhidharma said indignantly.

“Of course not, but give people a chance to get to know you. Remember, not everyone is born to the Warrior Caste, as you were. Take them one small step at a time and they will make the final leap when they are ready.”

The old ferryman had been right. Prajnatara was wise and Bodhidharma felt he had been enlightened all over again.

“Don’t misunderstand me,” Prajnatara smiled, “I admire your conviction, really I do. You’re not wrong when you say scriptures and rituals are not the true Way. Still, they point in the right direction. And besides, the methods themselves are not the real issue.”

“They’re not?”

“No. It’s the discipline required that is important. Even students who reach enlightenment may falter if they’re not strong. You have that strength—I saw it in you when you arrived. It’s in your blood. I knew that if you grasped the subtle beauty of The Way, you would never stray from the path, and nor have you. I did not give you the name Bodhidharma for nothing. You will be a great teacher one day.”

“When you gave me that name, I thought it was the greatest honor a man could have,” Bodhidharma said with a heavy heart. “Now it hangs around my neck like a curse.”

“It is neither a blessing nor a curse,” Prajnatara said. “It is simply your destiny. The name Bodhidharma will be known throughout the world. I have seen it in a vision, and these things cannot be ignored.”

“You are too kind, Master.”

“Nonsense,” Prajnatara waved his hand dismissively, “and besides, your disdain for the scriptures will not be an issue in China. In fact, it will be something of a blessing. I’m told there are very few translations of the Sutras into Chinese, and those that do exist are of dubious quality. Your “direct methods” as you call them will be a useful way to spread the teachings, at least at present.”

“You still want me to go to China?” Bodhidharma asked, astonished.

“Of course.”

“Even after everything I told you?”

“You are the perfect envoy,” Prajnatara said, nodding vigorously, “Trust me on this. And besides, I have already mentioned you to The Venerable Ananda and he agrees.”

“He does?”

“Completely.” Prajnatara hesitated, examining his fingers before continuing. “There is another reason why you were chosen for this task, a rather more pragmatic reason. You’re young and strong, and like I said, the journey is long and arduous.”

Bodhidharma was finally beginning to see why he had been chosen for such a mission, “Long and arduous?” he repeated slowly, I believe “long and perilous” were your exact words, Master.”

Prajnatara’s pained expression returned. “They were? Yes, well, perhaps I did say that. Look, I won’t lie to you Bodhidharma. I’ll give you the facts as I know them.” He paused to clear his throat. “The Venerable Ananda did inform me that several monks who went to China seem to have disappeared.”

“Disappeared?”

“They have not been heard from again.”

“How many, exactly?”

“How many what?”

“How many monks have never been heard from again?”

“Well I’m not sure of the exact figures. I suppose The Venerable Ananda might have some more precise statistics …”

“Just approximately,” Bodhidharma persisted.

“I believe four masters went to meet with the emperor of China in recent years. None succeeded.”

“Why did they fail?”

“Two were quite old, and the journey is very demanding. There are mountains of dangerous cold, treacherous rivers, endless deserts. It’s thought they perished on the way. On top of that, there are bandits and brigands in the hills. One may have been killed, or captured and enslaved. The fourth went by sea, a very long route. I believe his ship was either lost at sea or attacked by pirates.”

“I see.”

“The Venerable Ananda and I felt that a monk with a background like yours would be the ideal candidate to succeed in such a mission,” Prajnatara said lightly, as if giving an answer to a simple puzzle. “If your skill with the bow and the sword is even half as good as your wrestling, you should have nothing to fear. In fact, heaven help any bandit who tries to stop you!”

“You make it sound easy,” Bodhidharma scowled.

“It is not easy. Not at all. But then, the path never is. It is simply the path. And this is your path. Surely you can see that?”

Bodhidharma stared at him coolly.

“Besides,” Prajnatara continued, “it’s not all doom and danger. Think of the adventures you’ll have, the places you’ll see. You can go north to Magadha and bathe in the sacred waters of the Ganges. Make a pilgrimage to Bodh Gaya and meditate beneath the Tree of Enlightenment like The Buddha. You can visit Kapilavastu, Sarnath, and Kusinagara. And after all that, you can go to Nalanda, the greatest temple in the world, where The Venerable Ananda will be expecting you. He will help you prepare for your onward journey. You will climb the Himalayas and stand on the roof of the world. I climbed those mountains myself when I was young. They are so beautiful. I only wish I could see them once again before I die, but my place is here now. And then you will see China! Just think of it, an unimaginable land, known to the rest of us only through myth and legend. How I envy you.”

He stopped abruptly to gauge the reaction of his disciple.

“It sounds like the two of you have it all planned,” Bodhidharma said.

Prajnatara laughed. “The Venerable Ananda and I have written many times on the subject, that much is true. He is very excited about the possibility of your mission, very excited about you. But there is no need to answer right now, Bodhidharma. Think it over. Take as long as you wish. I know you will make the right decision.”

“There is no need to think it over,” Bodhidharma said quietly. “I will go.”

Prajnatara’s face lit up. “You will?”

“I will. If you say it is my destiny, then I will follow it.”

“How wonderful!” Prajnatara clapped his hands in delight. “The Venerable Ananda will be so thrilled when I tell him.”

“I would not want to disappoint the living embodiment of Buddha on Earth,” Bodhidharma said with a grim smile.

“Oh Bodhidharma, you could never disappoint him, nor me! But I’m so happy that you have accepted. It is your path. I have seen it in a vision, and these things cannot be ignored.” Prajnatara poured a little water for himself and took a sip. “On a more practical note, you will need more than your bowl and sandals for this journey. I will give you funds and provisions to help you reach Nalanda, and Ananda will help you from there. But we can make all those arrangements later, much later. First we should relax, and you can tell me where you have been wandering and preaching, and why you have waited so long before coming to visit us. I am very angry with you, young man, very very angry …”

And so it was that Bodhidharma set off for an unknown land beyond the Himalayas, a place he could only imagine from a painting he had once seen, long ago, in the library of a temple he had visited. The painting had been unusual, most unlike the richly colored art of India. With just a few bold strokes of black ink on stark white paper, the artist had created an enormous winged serpent coiled around sharp towers of rock. Angry white water seethed beneath it, and a fine silver mist hung in the air. Curious markings ran down the side—Chinese writing, he had been told—though no one had any idea of their meaning. The effect had been startling; an alien world filled with unknown dangers. It was a land that could not have been more different from the warm flat jungles of his homeland, a place that was now both his destination and, if Prajnatara was to be believed, his destiny.

Kuang Returns to Barracks

Huo bent to help Kuang to his feet. “Come on, you fool,” he sighed, straining to lift him, “let’s get you back to the barracks. It’s going to be freezing out here tonight.”

Kuang struggled to stand. His body was wracked with pain. He took two faltering steps supporting himself on Huo’s shoulder, but the pain was too great and his legs buckled beneath him. Huo caught him and lifted him in his arms like a baby, ignoring his groans. “No need to thank me,” he said.

Huo had a fat lip and his left eye was black and swollen, despite which, he appeared in good spirits. He had clearly fared better in Corporal Chen’s brutal training fights than Kuang had. “Why did you come and get me?” Kuang demanded sullenly.

“Corporal Chen sent me.”

“He did?”

“When I told him you hadn’t come back, he ordered me to come and get you.”

“That’s very caring of him.”

“Try not to annoy him, Kuang. Just keep your head down and don’t get noticed. That’s what I do. It’s the best way.”

“I don’t want to be like you.”

“Good. I don’t want to be like you, either.”

They continued in silence until they reached the torch-lit compound inside the fort. Commander Tang’s residence stood before them. The commander was the officer in charge of the fort, and as they drew nearer, Kuang twisted in Huo’s arms.

“You can put me down now,” he said.

“Don’t be stupid, we’re almost there.”

“Put me down.”

“Shut up,” Huo laughed, “or I’ll drop you here and leave you on the floor.”

“Come on, put me down, please …”

Huo gave in and put him down and Kuang walked despite the pain. Huo wondered why his friend was so determined to walk. Perhaps he didn’t want Commander Tang to glance out of the window and see him being carried like a baby. When Huo noticed movement on the terrace outside the commander’s residence, he guessed the real reason for Kuang’s reaction. Weilin was outside.

Weilin was Commander Tang’s daughter and often came out in the evening to tend her flowerpots or read a few pages from her book. Like all the soldiers in the fort, Huo watched her hungrily, from a distance. She was young and pretty. She was also the only young, pretty woman in the fort. But when it came to his chances with Weilin, he knew she may as well have been on the moon. Not only was she the commander’s daughter, she was also betrothed to Captain Fu Sheng, a cavalry officer who was stationed on the northern frontier. The captain visited the fort only rarely, but his reputation was enough to deter any young man who might have been foolish enough to make advances to his fiancée.

Tonight, Weilin was reading by lamplight. The flame flickered in the sharp mountain wind, catching the soft curve of her cheek, the ripe lips. Her eyes were buried in her book. As they passed by, Huo was surprised to see her look up. Normally she ignored the soldiers coming and going around the fort but this time he saw her gaze follow Kuang as he passed. In a sudden flare of the torchlight, he was even more surprised to see a look of concern cross her face at the sight of Kuang’s bruised and swollen face.

Kuang turned to hide his face from Weilin and hobbled toward the barracks as quickly as his aching legs would carry him. Huo hurried after him. “Hey, Kuang!” he whispered urgently, “don’t even think about it!”

Kuang ignored him and continued in silence.

“Seriously, Kuang … I mean it. I really mean it.”

“I don’t know what you mean,” Kuang said tersely as he mounted the barrack steps on stiff legs.

“Yes you do. You know exactly what I mean,” Huo persisted.

Kuang ignored him and went inside. Huo looked back toward the commander’s house. The flicker of the lamplight could still be seen in the distance. He waited a moment, watching the light play against the dark setting of the surrounding mountains, and then followed Kuang out of the cold night air and into the warm, stuffy embrace of the barracks.

A Pilgrim in Magadha

Bodhidharma crossed many rivers on his journey to the northern Kingdom of Magadha, but none stirred him like the Ganges. In the clear morning light, the vast expanse of sparkling brown water filled his vision. The river was the birthplace of a civilization and the artery that pumped life through the Buddhist heartland of Magadha. The Buddha himself had lived and preached all his life in this fertile plain. As Bodhidharma sat by the waters edge, he pictured The Buddha bathing in the sacred waters, speaking softly with his disciples, the river clean and uncrowded.

Things were very different now. Hundreds of people were gathered at the water’s edge and standing in the shallows, washing their hair, their teeth, their clothes, cupping their hands to drink the sacred waters of the Ganges hoping it would endow them with eternal good health. The swollen corpse of a goat float by, followed by the body of an old woman. Bodhidharma filled his goatskin from the murky waters, but did not drink. He would use it later for tea. He knew the difference between truth and myth.

He had crossed the Ganges once already on his way to Kapilavastu, the birthplace of The Buddha, and from here he had visited the other sacred sites where The Buddha had lived and died. Now he prepared to re-cross the river for the final destination of his pilgrimage. He waited on the riverbank until a boatman noticed him and steered toward him. The boat was already filled with passengers, but there was always room for one more, especially if that person was a holy man who would bring good karma.

Bodhidharma stepped into the boat and sat beside a young boy, who cowed away from him and nestled closer to his father.

“You are going to Bodh Gaya, Master?” the boy’s father asked.

“Yes, I am.”

“To see the Bodhi Tree?”

“Yes,” Bodhidharma smiled, “I have read about it for many years but never seen it.”

“It is a very special place,” the man assured him.

“Why do you want to go and see a tree?” the boy asked, forgetting his fear of the fierce-looking stranger.

“The Buddha was sitting beneath that very tree when he became enlightened,” Bodhidharma answered.

“What happened to him?”

“He saw the true nature of things.”

“And what was it?”

“That is a good question,” Bodhidharma laughed.

“Have you seen it too?”

“Perhaps.”

“What did you see?”

Bodhidharma leaned closer so only the boy could hear him. “What I saw was not important. It was the light that I saw it in.”

“What sort of light?”

“A very clear light.”

“If I become a pilgrim, will I see it too?”

“Maybe one day,” Bodhidharma smiled, “I certainly hope you do.”

The dusty road to Bodh Gaya was crowded with pilgrims. Some were tall and slender with light skin from the north of India. Others were dark, with round eyes and tight black curls from the south, like him. Still others had come from beyond the Himalayas. There were white-skinned men with brown hair and green-eyed women in colorful costumes who, he imagined, had traveled from Persia or another unknown land far to the West. He passed a group of traders with smooth skin and almond eyes. Their features brought to mind descriptions he had read of Chinese people but when he asked their origin, he discovered they were from Burma.

A busy market had sprung up on the road to the Tree of Enlightenment. Stallholders sold paintings, tapestries, statues, and carvings of The Buddha seated beneath the Bodhi tree. A throng of wagons and carts had become hopelessly jammed. The drivers shouted angrily at one another while their mules and oxen twitched their tails against the swarming flies. Bodhidharma passed single-humped camels from the deserts of Arabia, and two-humped camels from Bakhtar beyond the Hindukush. On the edge of the market, a group of mahouts stood in a tight circle and joked among themselves while their elephants munched on mountains of leaves and looked down on the chaos before them with laughing eyes.

The market gave way to a park with a low limestone wall around it and cultivated gardens on either side. In the center was an expanse of dry grass filled with pilgrims, and rising above them all, a giant fig tree. A steady stream of pilgrims was walking round the tree, chanting prayers. Their endless footsteps had formed a rut in the ground that had baked hard in the sun. Other pilgrims lay prostrate toward the sacred tree, and yet more sat facing it in meditation, rigid and determined, as if waiting for a miracle. Some had clearly been there for many days and were on the edge of exhaustion.

Bodhidharma found a space near a group of hermit monks who were seated in a circle. Their matted hair and beards hung to the ground. Their skeletal bodies had been smeared from head to foot with grey ash. One of them noticed Bodhidharma through half-closed eyes, and turned to take a closer look. He watched as Bodhidharma lit a fire and prepared to make tea and heat a generous portion of flat bread and spiced vegetables. Finally he caught Bodhidharma’s eye and gestured to him. “May I join you, Brother?” he called out. His companions glared and whispered to him urgently, but he ignored them.

“If you wish,” Bodhidharma replied.

The hermit rose with difficulty and took a few faltering steps toward him, unsure of his balance. He bent to sit down, but his legs gave way beneath him and he slumped in a heap on the ground beside Bodhidharma.

“What is it that you are doing, Brother?” he asked, breathless from the exertion of moving from his seat.

“Drinking tea,” Bodhidharma said.

“We drink only the water from the sacred River Ganges,” the hermit said, shaking his head disapprovingly.

“The river may be sacred,” Bodhidharma said, “but the water is dirty.”

“The water of the Ganges is the water of life,” the hermit said, his dark eyes boring into Bodhidharma’s.

“The river contains death as well as life. Take a look next time you’re on the riverbank.”

“So where did you get the water for your tea?” the hermit asked triumphantly.

Bodhidharma looked at the hermit who was grinning broadly now, his broken teeth huge inside his fleshless skull. “From the river,” he sighed.

“Ha ha!”

“The fire rids it of the spirits of the dead.”

“You believe that?” the hermit scoffed.

“I do, and it also makes good tea. Here, try some,” Bodhidharma said offering him his cup, “it’s very refreshing.”

“I cannot accept, but thank you,” the hermit said.

“Why not? Is it because you might grow to like it?”

“The Buddha told us to free ourselves from earthly desires.”

Bodhidharma took a sip of tea and smacked his lips appreciatively. “He did. But did he not also say that to deny oneself life’s pleasures is wrong too? Did he not speak of a middle path?”

“Maybe so, but where exactly does that path lie?”

“A good question,” Bodhidharma smiled, setting his flat bread to heat over the fire.

“And what is your answer, Brother?” the hermit demanded.

“In a place that cannot be named.”

“Then does it exist at all, one might ask?”

“Yes.”

“That is what you believe,” the hermit said, “but are you certain?”

“I am,” Bodhidharma said with a smile.

The hermit stared at Bodhidharma for a moment then looked around at the park of Bodh Gaya. He noticed his fellow hermits glaring at him and turned back quickly to the stranger in the black robe who was sipping his tea contentedly.

“If you are so certain of things, then why are you here?” he demanded.

“I am making a pilgrimage on my way to Nalanda,” Bodhidharma told him.

“You wish to study at Nalanda? I must warn you, it is very difficult to get in. They will turn you away at the gate.”

“I have an introduction,” Bodhidharma told him.

“An introduction, you say? From whom? They are very particular in Nalanda.”

“Prajnatara.”

“Prajnatara, you say? Master Prajnatara is your master? Why did you not say so before? Prajnatara is very famous here in Magadha, although I heard he went south many years ago to teach.”

“He is, and he did.”

“He must think very highly of you, to send you all the way to Nalanda.”

“He is sending me a lot farther than that,” Bodhidharma smiled. The hermit’s eyes darted over the body of the dark monk and examined his face, determined to take in every detail. “May I know your name, Brother?” he asked finally.

“Bodhidharma.”

“Bodhidharma, you say?” the hermit’s eyes widened in wonder, “and you were given this name by Prajnatara himself?” He shook his head urgently from side to side, “I should call you Master instead of Brother! Please forgive me.”

“You’re free to call me anything you choose,” Bodhidharma said, removing his flat bread from the fire and setting his pot of vegetables on the flame.

“I shall call you Master Bodhidharma,” the hermit said, pressing his palms together with a smile, “and I am honored to meet you. My name is Vanya.”

Bodhidharma reached for his bowl and began to fill it from the pot on the fire. “Would you like to share my food, Brother Vanya?” he asked.

Vanya’s face fell in dismay and he shifted uneasily where he sat.

Bodhidharma smiled. “Maybe later,” he said, “I can see you have no appetite at present.”

“Yes, thank you, Master,” Vanya said with relief. “Please don’t think me rude.”

Bodhidharma began to eat noisily, shoveling mounds of spiced vegetables into his mouth with hunks of flat bread and washing it down with slurps of hot sweet tea. Vanya watched uneasily. He wanted to look away, but felt the eyes of his fellow hermits on his back and did not dare to turn in case one of them should catch his eye. “Forgive me for being so forthright,” he said finally. “You eat and drink in a holy place.”

“I’m hungry,” Bodhidharma said.

“You cook for yourself, which is forbidden by the Buddhist law.”

Bodhidharma shrugged.

“And I see you carry possessions.”

“I am on a long journey, Brother Vanya.”

“How can a man who is truly free of worldly desire do such things?”

Bodhidharma looked at Vanya’s wasted body, the grey skin stretched painfully thin over protruding bones, the sunken eyes and festering sores that remained untreated on his limbs. “The Buddha once did as you do, Brother Vanya,” he answered. “He denied himself and starved himself for many years. In the end, he abandoned that path saying the true Way lies neither in denial nor excess.”

“But to put oneself above the suffering of the great Lord Buddha, that could be considered pride, one of the greatest of all sins,” Vanya said.

Bodhidharma rinsed his cup and bowl and set about packing his knapsack, but Vanya had not finished. “Detachment, that is the key to all things. That is what The Buddha said. Freedom from desires and cravings. Freedom from revulsion and loathing, until even death no longer holds any fear for us.”

Bodhidharma rose to his feet and slung his knapsack over his shoulder. “Your mind is made up Brother Vanya, and my path takes me elsewhere. I wish you well.”

“Detachment is freedom from the wheel of birth and death,” Vanya said repeating a mantra that he and his companions lived by.

Bodhidharma planted his walking staff firmly in the ground. “Quite right!” he said, and then bent low so none but Vanya could hear. “Just beware of attaching yourself to detachment.”

He walked swiftly through the throng of pilgrims, surprised by the strength of his sudden anger. The hermit had studied for many years, yet he was still so blind. Not for the first time, he wondered if he had the strength to enlighten a single person, let alone the emperor of China. His furious pace took him quickly through the crush of the marketplace, and by the time he had reached the road to Nalanda his anger was replaced by a sadness that reached deep into his bones. His pace slowed and his knapsack felt heavy on his back. Finally he stopped and closed his eyes in despair.

Suddenly, there was the sound of urgent footsteps behind him.

“Wait, Master, please!”

It was Vanya, gasping for breath as he spoke, “I would like to walk with you, if I may. Please, wait a moment. I wish to follow The Way as you do. Let me travel with you as your disciple.”

“No,” Bodhidharma said, setting off again on the road.

“Wait just a moment, I beg you,” Vanya spluttered.

“I’m sorry,” Bodhidharma said without looking back. “My path takes me far from here. I suggest you find a different teacher.”

“But you said you were going to Nalanda,” Vanya said, urging his wasted legs to go faster and catch Bodhidharma.

“I am going a lot farther than Nalanda.”

“How much farther?”

“To Nanjing.”

“I have never heard of it. Is it far?”

“Very.”

“Let me go with you, at least as far as Nalanda. I have so many questions for you.”

Bodhidharma walked. Vanya stumbled along beside him, his head so full of questions that he could not think of a single one, and soon he was too tired to utter a single word. Bodhidharma’s relentless pace quickly became too much for him and he fell behind. But Vanya knew the way to Nalanda and kept Bodhidharma in sight, far ahead in the distance.

When darkness descended and Bodhidharma stopped to rest, Vanya joined him by the fire, just as his little pot of water began to boil. Too exhausted to speak, he simply smiled happily at Bodhidharma, as if they had been traveling companions for so long that words were no longer needed. Bodhidharma handed him a bowl of rice and a cup of hot, sweet tea and this time Vanya ate and drank without protest.

Flowers on the Balcony

“Come on, my friend,” Huo said, pulling on his overcoat and heading for the door of the barrack room. “Let’s go to Longpan. We’d better hurry up, or all the pretty girls will be gone.”

Kuang remained on his bed and stared at the bunk above. “I’m not your friend, Huo, and I’m not going into that stinking town.”

Huo turned back and walked over to the bunks. He noticed Kuang’s face had almost healed from Corporal Chen’s brutal training session. The scab on his lip had all but disappeared and his left eye had reopened. The ugly swelling had gone down and only a little yellow bruising showed around his cheekbone.

“If I’m not your friend, then who is?” he demanded.

Kuang ignored him.

“Anyway,” Huo continued, “why are you sulking? It’s the end of the week. We need to relax. Come on, it’ll be good to get away from the fort. There’s nothing for you here.” He paused to let his meaning sink in. Still Kuang didn’t answer.

“Don’t be an idiot, Kuang!” Huo said finally.

“What do you mean?” Kuang said.

You know what I mean. I saw the way you were looking at Weilin.”

“She was looking at me!”

“She’s just bored—don’t flatter yourself. Weilin is Commander Tang’s daughter and she’s engaged to Captain Fu Sheng.”

“What about it?” Kuang said.

“Fu Sheng would tear you apart if he even suspected.”

“I’m not afraid of Fu Sheng. Besides, it’s none of your business.”

“I’m trying to help you, you idiot!” Huo said.

Kuang glared at Huo, his temper rising. Then he remembered how Huo had carried him back to the barracks when he had been too weak to walk, and the anger left him. “I’m staying here,” he sighed. “You go to Longpan. You don’t need me.”

“Have it your own way,” Huo shrugged and made for the door.

“I never did thank you for the other day,” Kuang called after him.

“No, you didn’t.”

Huo stood in the doorway as Kuang searched for the right words, then gave up waiting. “Never mind,” he said, stepping out of the barracks and into the dusk. “There really is no need.”

Kuang sprang up and checked his face in the polished brass that served as a mirror. He wondered whether to wait another week, but when he thought of Weilin’s pretty eyes and slim waist, he decided he had waited long enough.

He left the barracks and crossed the compound, keeping to the shadows. When he reached the commander’s house, Weilin was not in her usual place on the terrace. He wondered what to do. He could not stand around idly. Someone would soon notice him. Perhaps he would go into Longpan after all, get some food, a few drinks, perhaps a girl—someone to pass the time with until he could have the girl he wanted. He turned to go. He had only gone a few paces when he heard the faint click of a door opening behind him. Weilin was on the terrace. She glanced at him for a moment, then set about rearranging her flowerpots.

He sauntered over to her and stood in the shadows nearby. “Is something the matter, Miss?” he asked with a smile.

“Perhaps I should ask you the same thing?” she answered without looking up from her work.

“What do you mean?”

“It’s not me who is skulking in the shadows,” she replied without turning to look at him. “Is there something you want, soldier?”

“You don’t know my name?” he asked.

“Why would I know your name?” she asked icily.

Things were not going as he had hoped and he began to wonder if he had made a mistake after all. “I know your name,” he continued lightly. “You’re Weilin. I’m very pleased to make your acquaintance. My name is Kuang, from Hubei.”

“In that case, I do know your name,” she said. “In fact, I have often heard it mentioned in my father’s house, usually when trouble is discussed. Now I can put a face to the name.”

“Then at least you know my face,” he smiled, hoping to seize a small victory.

“Who wouldn’t know your face? It stands out from the rest, even among the battered faces I see here every day.”

He touched the remains of the scab on his lip before he could stop himself. He was getting nowhere. She clicked her tongue and busied herself with her flowerpots, picking out dead leaves and pouring a little water into each.

“I know your face,” he said finally. “It stands out too, but for a different reason.”

She ignored him.

“You’re very beautiful,” he said, almost to himself.

She looked at him then, waiting for a further remark, but there was none.

“That’s kind of you to say,” she said at last, “but I don’t think so.”

“Oh, it’s true,” he smiled, “believe me.”

“What is it you want, exactly, Kuang?”

“I came to tell you that you’re the most beautiful woman in the whole of Yulong Fort,” he said with a mischievous smile. Her face hardened. It was hardly a compliment, considering the age of the few other women who lived in the fort. Then, seeing the humor in his eyes, she relented and laughed despite herself.

He stepped up to the balcony rail with a broad grin and she saw how handsome he was beneath the cuts and bruises. “If someone sees you here, there’ll be trouble,” she warned.

“No one will see me. Besides, we’re only talking, nothing more.”

“Why aren’t you in Longpan this evening like everyone else?”

“There’s nothing for me in Longpan.”

“I’m sure there are plenty of pretty girls.”

“None like you.”

“You’re out of your mind, Kuang!”

“Maybe,” he said, reaching over the rail for her hand and drawing her to him slowly, drawing her so close he could only see the curve of her cheek and the top of her lip. He leaned forward to kiss her. To his surprise, she did not resist. When a lingering moment later she pulled away, he drew her back and they kissed again.

“This is a bad idea,” she whispered urgently. “You shouldn’t be here. If someone sees you, there’ll be serious trouble.”

“There’s no one around,” he assured her. He vaulted the balcony rail and pulled her body to his, pressing his lips to hers. His hands cupped her neck lightly, then smoothed down her back, settling on her slender hips. His knee found its way between her thighs. Her body tensed. He wondered if he had gone too far when he felt her press into him, her small hands pulling on his shoulders.

A sound came from inside the house—a door closing—foot-steps in the hall. Kuang vaulted back over the rail and darted into the shadows. Weilin returned to her flowerpots. They waited, breathlessly, but no one appeared. He returned to the terrace, but she put her hand on his chest to prevent him from jumping over the rail. “I’m betrothed, Kuang! I’ll be married soon. And don’t forget to whom. You know what Fu Sheng would do if he found out.”

“I’m not afraid of Fu Sheng. I’m not afraid of anyone.”

“You should be. He would kill you. He would probably enjoy it,” she shuddered.

“But where is Fu Sheng now? Out in the steppes, more concerned with killing Turks and Uighurs than with being with you. If I was him, I would never leave you on your own.”

“Fu Sheng has important duties.”

“Your father arranged the marriage?” Kuang asked.

“Father did what’s best.”

“Best for who?”

She looked so sad that he did not know what to say next. Instead he kissed her and she did not resist.

There was another noise from the house. He leapt away into the shadows just as Weilin’s mother put her head out.

“Are you out there, Weilin?” she called.

“Yes mother, I’m tending the flowers.”

“You’ve been out a long time. It’s cold tonight. Come inside and sit with me. Keep me company.”

“I’m coming, mother.”

She looked at the shadows where Kuang was hiding, turned away, and was gone before he could say anything.

He waited for a minute, before returning to the barracks. The empty room was cold and silent. He lay on his bunk and closed his eyes, thinking of Weilin. Kissing her again. It was a dangerous game he was playing but he did not care. Whatever happened, he had to find a way to be alone with her again.

Monks Enter Nalanda

“There it is, Master,” Vanya cried, “Nalanda!”

The point of a giant stupa rose over the treetops, glinting gold against the blue sky, and Bodhidharma felt his heart quicken. He had read many descriptions of Nalanda and seen its golden tower in countless paintings, yet nothing had prepared him for the sight of it rising before him. Nalanda was the jewel in the Buddhist crown, a monastery the size of a city, the greatest temple on earth. Monks came from all over the world to sit in its lofty lecture halls and study in its libraries, which, it was said, housed over a million books and scrolls. The stupa towered over everything, dwarfing the trees that grew nearby, reminding all living things of their place in the world—they were a mere speck in the universe, their lives as temporal as that of an insect, over in the blink of an eye.

Nalanda’s outer wall was high enough to defend a fortress. A row of brightly colored flags fluttered in the warm breeze and palm swifts darted overhead. At the entrance, two guards stood by enormous doors of black wood and iron. The doors barred the way inside save for a small gap between them. There was a young man talking with the guards and as they drew nearer, Bodhidharma could hear them discussing a passage from the Lankavatara Sutra. He turned to Vanya for an explanation.

“They do this, Master,” Vanya whispered loud enough for all to hear. “They ask questions about the scriptures. It’s a test. You can’t enter Nalanda unless you know the answers.” He lowered his voice so that only Bodhidharma could hear, “I have tried several times myself, but they were never satisfied. I think it’s because I’m not of noble birth.”

Moments later, the young man was turned away by the guards and brushed past them in obvious distress. Then the elder of the guards glanced at the two waiting figures. “State your business at Nalanda,” he said curtly.

“I am here to meet with The Venerable Ananda,” Bodhidharma said.

The guard glanced at the wild-looking monk, taking in the shabby robe, the bare feet, and the skin beaten black by the sun. He was little more than a beggar. “The Venerable Ananda does not give an audience to casual visitors,” the guard said.

Bodhidharma had only to produce Prajnatara’s letter of introduction, but he did not. Instead he planted himself firmly before the guard. “He will see me.”

“On what business?”

“No business of yours, Brother,” Bodhidharma answered, “and before I see him, perhaps you can enlighten me on this practice of turning away young monks who wish to study and barring the gates of a monastery to visitors?”

The younger guard stepped across to stand by the shoulder of his companion, who was about to answer when Vanya hurried forward and spoke quickly. “Brother Guards, it appears you have failed to recognize Master Bodhidharma! He is a disciple of Master Prajnatara himself and has traveled all the way from Pallava to meet with The Venerable One.” He leaned closer to the guard, speaking in a whisper, “You’re keeping him waiting at the gate like a novice. Do you think that wise?”

The senior guard hesitated.

“Perhaps you want to debate the scriptures with him?” Vanya smiled.

“No one is allowed into Nalanda without the correct papers or authority,” the junior guard said. “Those are our orders.”

“You are following orders. That is very commendable,” Bodhidharma said, keeping his gaze fixed on the senior guard, who looked more closely at the stranger before him. This time he noticed the expanse of hard muscle beneath the threadbare robe. The man was built like one of the wrestlers who competed in the arena at Rajagriha. His bulging forearm suggested many years of wielding weapons and the calloused fist that gripped the walking staff was that of a Vajramukti master, able to shatter bone as easily as snapping a twig. The guard looked into the fierce black eyes and saw that if the stranger wished to enter, two guards would not delay him for more than a heartbeat. At that moment, Bodhidharma smiled.

The guard made up his mind. “I will escort you personally,” he said, hushing the objections of the younger guard with a frown.

He led Bodhidharma into the monastery and Vanya hurried after them before anyone could object. In the broad courtyard, monks and nuns strolled in pairs, deep in conversation. Novices hurried to their lessons with scrolls under their arms and senior monks sat with one another in the shade of the many trees. The guard led Bodhidharma and Vanya down a wide avenue that ran between the many lecture halls, libraries, and temples of Nalanda. They entered a beautiful garden with fruit trees and flowerbeds of orange, purple, white, and yellow. Young monks bathed in tranquil pools of spring water. Towering above them all was the great stupa of Nalanda, so high that from where they looked, its top disappeared from view.

They entered a great hall lit by a wall of lamps and decorated with exquisite tapestries depicting scenes from The Buddha’s life. A gong as tall as a man stood in the entrance and reflected the flickering lamplight in its gleaming surface. An attendant monk emptied incense from a burner and ghostly clouds of white dust caught the lamplight and swirled up toward the ceiling.

The guard spoke privately with the attendant before bowing to Bodhidharma and taking his leave. The attendant introduced himself and led the two visitors down a maze of dark halls and passages. They climbed several long flights of stairs and Vanya became breathless with the exertion. On the upper floors, the corridors were brighter and the ceilings higher. These were the living quarters of the senior monks and sunlight poured in through high windows, falling on bookshelves filled with scrolls and manuscripts, comfortable seating areas and quiet rooms for private study. They passed a little meditation hall that housed a beautiful gilded shrine, complete with offerings to The Buddha and freshly cut flowers from the gardens.