Читать книгу Secret Pigeon Service - Gordon Corera - Страница 14

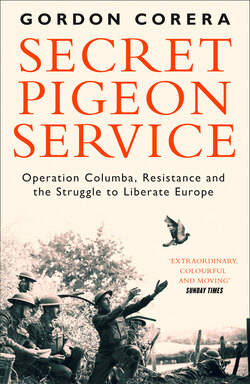

Leopold Vindictive

ОглавлениеThe Debaillie family gathered in the large building in Lichtervelde that doubled up as a grocery store and a family house. A local farmer had found the pigeon in the field that July morning in 1941 and his wife had brought it to them hidden in a sack of potatoes. It was just over a year since the Nazi war machine had swept through Belgium and the farmer had taken it to the Debaillies because he knew they were patriots. But now the family had to decide what being a patriot really meant.

Their task was initially to decide the pigeon’s fate – and perhaps with it, their own. The decision was far from easy. The three brothers, Gabriel, Arseen and Michel, and two sisters, Marie and Margaret, deliberated over what to do with the bird. Two of the brothers differed. Gabriel thought it best not to get involved. It was true the family were ‘patriots’ who hated the Germans, rather than ‘blacks’, but they had never engaged in any overt act of resistance. The risk was too great. They had too much to lose. But Arseen felt the need to act. He was the most ambitious of the brothers and the keenest to take risks. The pigeon had come to them with a call for help and they should not turn it away – it was their duty. Even though he was the youngest brother, he got his way. Margaret, the younger of the sisters, backed him, whilst her elder sister Marie was more cautious.

Once the decision had been made, there was no reluctance or dissent on the part of the other members of the family. They were and remained united. Their father, the founder of the business, had died a few years earlier and the siblings were a close-knit family who ran the concern together and knew they could trust each other. Spying would be a family affair. But what were they actually going to do? They knew that to make the most of the opportunity that the pigeon had brought their way, they needed help. And so they turned to two friends. One was Hector Joye from Bruges, who spoke English and loved military maps. The other was a Catholic priest, Father Joseph Raskin. The Debaillies knew Raskin through another brother of theirs who was a missionary in China. He had been taught by Raskin and had invited the older priest to stay with the family before the war. The priest had become a frequent overnight house-guest, with his own regular room. The two sisters, Marie, aged 48, and Margaret, nearly 40, were particularly devoted to Raskin. In turn, Raskin was a friend of Hector Joye, having presided over his wedding. So the circle of trust between the friends was complete. This was the way many early resistance groups were born – not as soldiers or spies but as groups of friends who felt such deep anger at the occupation of their homeland that they were willing to accept the risk of trying to do something about it. The bonds of friendship offered trust and some degree of protection but this often had to compensate for a lack of experience in the world of espionage against a formidable enemy.

Within a day of the pigeon’s arrival, the budding spy ring had gathered in Lichtervelde. Joseph Raskin would be the central figure. For all his outward trappings of a priest, it was as if everything in his life up to this point had prepared him for his career as a spy.

Raskin had been born in 1892 in a comfortable, detached house in Stevoort, a village of a few hundred families who all knew each other. His father had become a teacher and then principal of a local primary school. Joseph was the eldest of eleven siblings – the one they all looked up to and idolized. Culture and Catholicism were the defining characteristics of a family who would pray, sing, draw and read poetry together. From the time he was a small child and grabbed a rattle or moved to the piano, it was clear Joseph had a love of and gift for music. But the church came first. The headmaster of Joseph’s school had a brother who was a missionary and his letters from far-off lands would be read out to the pupils. That inspired Joseph to follow in his footsteps, and in 1909 he left home and joined a Belgian missionary organization called CICM – known as the missionaries of Scheut or Scheutists, after the neighbourhood of Anderlecht in Brussels where they were based. It was a strict regime – up at 5 a.m., asleep at 9 p.m., the hours between filled with prayer, study and communal living. Family visits were limited, but when Joseph returned for a few days’ holiday in 1912, his siblings found he had grown up. He was still not tall, and he continued to walk with a slight stoop that had been there from childhood, but now he proudly sported a short beard, much to their amusement. Joseph and his youngest brother would become missionaries and another brother a priest. Two of the sisters would become nuns.

When Germany declared war on Belgium on 4 August 1914, Raskin had just been ordained a sub-deacon, but he was not immune from the patriotic fervour sweeping Europe. God and country were intertwined for many at that time. But Raskin’s family were about to see up close what war really meant.

The family had moved to the town of Aarschot a few years earlier, when Raskin’s father became a school inspector. It was a small town but would become famous both in Belgium and Britain for the events of August 1914. As the Belgian army retreated, two Belgian regiments acted as a rearguard in the town and held up the German advance, much to the anger of German commanders. In their house, Raskin’s younger siblings hid in the basement and sat fearfully around a single lamp, occasionally going upstairs to peek at events from behind the curtains. When the town fell, twenty captured Belgian soldiers were shot and thrown into the river. That evening a German brigade commander was shot while standing on a balcony on the square – perhaps killed by the ricochet of a bullet fired by his own soldiers. But the Germans treated the death as an assassination and began heavy reprisals aimed at what they saw as resistance from the local population. Men were rounded up in the marketplace and then taken to a field where they were executed. In all, 156 civilians were killed over the following days. Women were said to have been victimized. The events in Aarschot were pivotal in what came to be known in Britain as ‘the rape of Belgium’, an episode ably exploited by British propagandists as their country responded to the attack on neutral Belgium by joining the war. The British spy and author William Le Queux wrote graphically of babies being bayoneted and women savaged by the German army in the town. British newspapers were filled with lurid, exaggerated accounts, which in turn helped galvanize support for war amongst the British public. And so Belgium’s war quickly became Britain’s.

The first time Joseph Raskin was arrested as a spy by the Germans he was entirely innocent. Priests and primary school teachers had been mobilized as stretcher-bearers and ambulance men for the Belgian army. Raskin was put to work at Beverlo ferrying wounded soldiers around. As word reached him of events in Aarschot, he became desperate for news of his family. At 6 a.m. one Sunday he put on civilian clothes and got on his bike. A German patrol stopped him. A young man cycling in civilian clothes was highly suspicious at a time when the Germans thought every Belgian was a spy. Worse, Raskin did not have his Red Cross papers. The case seemed open and shut. He must be a spy. The sentence was death.

Raskin was taken to a fort that was being used a prison. In a car on the way he noticed that the papers regarding his case were lying on the seat next to him. He slowly edged them underneath him and then to the other side. As the car hit a particularly violent bump, he pushed them out of the side without the Germans noticing. Upon his arrival at the fort, the authorities were lost without the paperwork. In the chaos of the early days of the war, there was nothing that could be done. He would just have to be kept there.

In December 1914, he made his escape from the fort. The family story was that he hid under the hay in a wagon on the return journey of a farmer who had come to deliver food. The reality may have been somewhat more prosaic. German papers indicate that they had been unsure what to do with him, and because he had made himself useful as a cook he was allowed to travel to Stevoort in early December. It was from there that he may then have made his escape, perhaps indeed in a hay cart. Whatever the real story, he was out. He then went to the front lines, again as a stretcher-bearer. This was dangerous work, sometimes involving making one’s way right to the front to load up the battered and broken bodies of soldiers and then suddenly having to drop into the mud as German bullets whistled overhead.

He enjoyed a ten-day break in London – not knowing that a quarter of a century later the course of his life would be shaped by his attempts to reach out to that city once again. During that brief visit, there were visits to churches and museums, but Raskin had one problem. With his lively blue-grey eyes, rippled dark hair and infectious laugh, he was handsome, and he wondered how to explain to the local girls who seemed interested in him that he was actually a chaste priest.

When he returned to the front, Raskin’s peculiar skills opened the way for him to become something else – an artist-spy. Since his youth, he had been good with his hands as well as his head. He would repair clocks and generally tinker with things. He was particularly talented as an artist. So now, he began to go to the front line, initially of his own volition, to draw what he saw in front of him. The result were beautiful drawings of the trenches and German positions.

When his superiors in the Army saw the drawings, they immediately recognized their military value and they were passed up the chain of command to the highest levels. Raskin was dismissed as a stretcher-bearer and turned into an observateur – a kind of intelligence gatherer. He worked across the Belgian front, just north of Ypres where the British were fighting. It was a bleak, apocalyptic landscape. The Germans had initially advanced over the River Yser but the Belgians flooded the land to halt their advance. The Germans then partially retreated back over to one bank. The land in between was laid waste by a mix of water and war. Sometimes the two sides were close – at a place called the ‘trenches of the dead’ they were little more than twenty metres apart. But in other places, no man’s land was far wider and less clear-cut. Shredded trees stood amongst pools of muddy water with the remnants of farm life surrounding them. The Germans had established advanced observation points and positioned snipers in farmhouses across the desolate flooded plain.

Raskin would travel out at night. He would give a password to a sentry and then sleep for a while in a shell hole. At first light, as the birdsong began, he would begin to observe and sketch. Two men would accompany him and provide covering fire if needed. At night, when he had seen enough, he would return. Back in his bureau he would take the rough drawings he had made and turn them into something approaching art. There are beautiful pencil drawings and watercolours of the view from the Belgian side facing the Germans, with each German position carefully marked out. The largest, most dramatic panoramas he made are two feet long, works of art crafted from the art of warfare.

It could be dangerous. In mid-May 1916, he spent three days and nights without food or water trapped in an abandoned flour mill, full of rats, surrounded by Germans. Another time, a bullet shattered the lens of the periscope he was using.

Sometimes in the picture is what appears to be an abandoned building. Look closely and you can just see the eyes of a German soldier hiding in a gap ready to shoot. A caption notes that this was a permanent German observation point. There were also bird’s-eye views of the same front lines, again marked out in precise detail with map coordinates and distances. One map has arrows indicating not just the direction in which the Germans shot from each trench but how regularly they fired; for instance, whether they only fired in response to Belgian fire or just at night. At one farmhouse, it is noted that every time the Belgian artillery began firing, a German periscope popped up. At another point it is remarked that the Germans at night sent out patrols so close they would throw grenades into Belgian trenches.

Senior officers were impressed. One went so far as to put his signature on one of Raskin’s pictures, which led the priest to realize he needed to sign them himself to prevent others taking credit. In spare moments, the priest’s humanity shone through – he would make small pencil drawings of an exhausted fellow soldier having a cigarette or devouring a chunk of bread. And so, without knowing it, the first stage of his preparation for the English pigeon scheme was complete. Raskin had learnt the fine art of military intelligence – which information was of value, and how to present it.

When the war ended, Raskin became, as he had always intended, a missionary-priest. After celebrating his first mass, he boarded a white steamboat for the long journey to China. Pictures show the young man lounging on a bunk with fellow priests in second class and out on deck with a mixed group of priests and nuns, all smiling as they head out on their adventure. On the long voyage, Raskin would play the piano in the evening or draw pictures of fellow passengers. They made their way via Port Said and the Suez Canal, Singapore and Hong Kong before finally reaching China. A photograph shows Raskin in Shanghai, dressed in local clothes, learning how to write the local language. And here was the second phase of his preparation for the pigeon operation – the ability to write beautifully and precisely as he learnt how to trace Chinese characters. The quality of his handwriting would win him a prize in Shanghai and would later be useful in condensing information into a tiny space.

His training complete, Raskin made his way to the heights of Mongolia. There he worked at a school training Chinese priests. He became the closest thing to a local doctor, dealing with ulcers in particular. ‘I have more consultations than confessions. That is not good,’ he would joke. The part of Mongolia he lived in was the Chinese equivalent of the Wild West. Local warlords would rampage from village to village, looting and killing. Raskin organized the villages so that a signal fire could be lit from a hilltop which could be seen by watchers in other villages to warn them of attack.

After the best part of a decade in China, he was summoned back to Brussels by the chief of the Scheut mission house. His varied skills meant he was needed as what was called a ‘propagandist’ – a travelling preacher who would go from town to town spreading the word about the missions to raise funds and persuade people to support the organization or become missionaries themselves. In his diary in Mongolia, he wrote of his disappointment at the order to return. ‘My soul is sad as if it has died.’ But then, in Latin, he adds: ‘Your will be done.’ Back in Belgium, he would criss-cross the country giving talks about China. Here was another stage in his preparation – building up a wide-ranging network of friends, supporters and contacts.

As the years passed, Raskin became rounder and seemingly smaller, the lines on his face deeper. But still he could attract people round him with his laugh and his story-telling.

And then war came again. Another invasion of neutral Belgium. But this war was not like the one before. This time there were no trenches or static front lines. German tanks, accompanied by the terrifying air power of the Luftwaffe, ripped through Belgium in a matter of days. Raskin acted as a chaplain to soldiers in Torhout during the dark days of May 1940, visiting the nearby Debaillie family in Lichtervelde wearing the uniform of a captain. Within eighteen days, Belgium was occupied by the Nazis. Initially, the Germans promised that if there was compliance there would be no need for brutality. But for many Belgians that did not quell the desire to do something. Unlike France, it was a country that had been occupied and invaded many times before. There was almost an ingrained sense in many Belgians of how to find ways to live under occupation while also getting the better of the occupying power. For some that meant small acts of defiance, for others something more risky. Resistance would emerge faster and with greater strength in Belgium than in many other countries, including France. But it would still take time to recover from the shock of defeat and for resistance to become organized. For the first few months, the urge lay largely dormant and barely visible, like a flower bulb beneath the hard earth. By the summer of 1941, it was ready to push through into the open.

This was how resistance often emerged in occupied Europe. Not as the result of activity from London on the part of British spies or exiles, but as groups of friends spontaneously coming together because they hated the German occupation and were desperate to do something about it. People would hang out in cafés, conspiring, starting to collect what they knew might be useful information about the enemy they could see around them, but often with no way of transmitting it to Britain. Now, suddenly, Columba presented some people with an opportunity. Could it act as a link to the nascent resistance?

And so, after a year of occupation, Raskin received the phone call from Arseen Debaillie. The next day he was there in the corner shop, in front of him the pigeon and the two sheets of rice paper, along with a patriotic appeal from Britain for help. He never had any doubts about what to do. Raskin, Hector Joye and the Debaillies made their decision. They would answer the call. They agreed amongst themselves that they would split up over the coming days to maximize the amount of information they could collect.

Arseen, the youngest of the brothers at the age of 27, nevertheless looked the oldest with his broad chubby face and glasses. He was the chief enthusiast and spy amongst the three brothers, although the family would work together as a team, its members supporting each other. Arseen spent the next few days driving along the coast and through the neighbourhoods around Bruges taking notes. Gabriel, thirty years old and the most anxious of the three brothers, would maintain the cover of working the family’s growing business – supplying animal feed at Roeselare. But he also went with his brother on a car trip to the coast, ostensibly for business but also to see what information they could gather.

Michel, the gangly pigeon fancier, tended to stay at home. The pigeon had arrived just a fortnight before his thirty-second birthday. As a child he had suffered from rheumatic heart fever, a condition which had left his heart damaged and required him to see a doctor every few weeks. His comfort, like those in Britain who had supported Columba, were his pigeons. Sundays were the days he liked to spend with his birds, often racing them at Lille. He kept them in a large, sideboard-sized coop on the ground floor of the building.

Hiding the British bird carried risks. Immediately after occupying Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium and France, the Germans imposed controls on pigeon owners that were progressively tightened. In Belgium, the country’s Fédération des Colombophiles had to keep a register of every pigeon, and the Germans checked this regularly. Pigeon keeping would later be forbidden entirely in a number of districts in Belgium and northern France, matching closely the places where the Columba birds were dropped. Sometimes messages brought back by Columba pigeons revealed the pain this brought to those who loved their birds. One message reported a plea to British owners: ‘Rear a couple of young pigeons for me. I have to kill all mine.’ But Michel and the family were willing to take the risk. It was not too hard for him to hide one special bird that was different from the others.

Marie and Margaret, the two sisters, had their role. They would maintain the appearance that everything was normal at the shop, chatting away with customers while looking out for any signs of trouble. Raskin would go back to Brussels and gather material from there. He would also ask friends whom he trusted for any information they had.

Hector Joye had the time – and the cover – to travel. He had been a soldier in the First World War but while in the trenches he had been gassed by the Germans and was now invalided. During that war he had met Louise Legros, who worked for the Red Cross. Her well-to-do family had been opposed to their relationship, but one person who had encouraged them was Raskin. Theirs had been the first marriage he had conducted as a priest. Louise’s career had taken off and she had been appointed the director of a girls’ school in Bruges. The family lived in comfort in a house that was part of the grand, Gothic school complex. A family picture shows Raskin enjoying a lunch in comfortable surroundings with the Joye family all around – his visits were always the occasion for a party, events that the Joye children enjoyed.

Handsome, with swept-back fine dark hair, round glasses and a trim moustache, Joye was another tinkerer with similar hobbies to Raskin. He had once been a carpenter, had designed a heating system for some nuns and had built incubators for the eggs of the pheasants he kept. His finest invention, his son would remember, was a special Christmas tree mobile containing a mechanism that enabled the angels to fly around. As a former military engineer, he was fascinated by maps and fortifications. Like the others, he was a devout Catholic for whom serving God, king and country were as one. Because of his health, Joye had permission to travel up to the coast to get fresh air. With little to do (not least in comparison to his wife), Joye was enthusiastic at the opportunity to turn his hand to espionage.

The amateur spies needed to work fast. The pigeon could not be kept too long. But they were determined to make the most of their opportunity. The amount they collected was astonishing. They fanned out to discover what they could on their travels. Joye was the busiest. There was a particularly interesting chateau near Bruges occupied by German troops, he knew, and airports, and ammunition warehouses and factories producing material for the Wehrmacht. He would see what he could find. Arseen knew about the Bruges–Ghent railway line and a local aerodrome near their house, and could give details about the local population. Marie and Gabriel provided specific information about a nearby chateau. Raskin meanwhile seemed to have a stack of information ready to go. Some of this came from the network of contacts he had built up in Brussels, many of whom were women he knew through the church, and who were beginning, if haphazardly, to gather details of what they observed. Raskin tapped these friends for information. One letter to ‘my good Father’ from those days provides information about a German storage building in Brussels, and includes a drawing as well as details of munitions.

After days of frantic gathering, all the precious intelligence had to be squeezed into the two tiny sheets of rice paper the British had supplied with the pigeon. Raskin’s experience as a cartographer in the First World War and from China as a calligrapher meant he would be the one to write it all up. The Debaillies had just the place for him to work. Their corner shop was the public face of the business, where customers could come in and out. But the building was more of a mini-complex. There was an adjoining house where the family lived. And then, round the back of the shop, past a small, closed interior courtyard, was a structure used as a warehouse to store all the goods. At the beginning of the war, fearing German bombs, the family had built a windowless concrete room towards the back. Relatives would send their children out to Lichtervelde because it was thought less dangerous, and this room was their hiding place. The room had a bed in it where the children could sleep at times of danger, and a strong lock. It was what you might today call a safe room. It was perfect for spy-work.

A niece called Rosa, the daughter of another sister, was only eleven but was staying with the family. She was fond of Raskin. He wrote a rhyme, ‘Doosje van Roosje’ (little Rosa’s little box), on her sewing box and taught her to play the accordion the family had given him as a gift. She remembers Raskin was there more than normal during those days of July 1941. Something different was happening, she knew, but no one told her what it was. That would be too risky, in case she talked. She does remember one of her aunts – Marie, she thinks – heading into the safe room more often than she normally did.

At a table underneath a light in the safe room, Raskin pored over the drawings and details that came in, the spider at the centre of a web of espionage. The drafts of the maps and notes have miraculously survived, pages and pages of them, different types of notepaper and different handwriting reflecting the many hands that contributed to the work. Space was tight. Everything had to fit on two pages, and that meant decisions. Like a ruthless sub-editor at a newspaper, Raskin scribbled out lines with black pen where he thought the detail was superfluous. A line about the Germans taking too many potatoes from people is crossed out, as are general complaints about poverty and life being expensive. That was not hard intelligence, he knew. The next line of a draft, though, stayed in for the moment – how the Germans went from carriage to carriage on trains taking food from people, sometimes even slurping raw eggs. Also retained was a line about how people were taking the copper of phone cables between Bruges and Ghent. A line about how people longed for the English and would point out the blackshirts was scribbled out. Raskin was careful to stick to the exam question – answering the specific queries that the pigeon had carried to them and not inserting extraneous information.

The pigeon sat just round the corner at the ready. For Raskin, it may have represented something more than just a messenger. The pigeon – referred to by its proper name, the dove – has a powerful symbolic role in Christianity. When Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist, ‘the Holy Spirit descended on him in bodily form like a dove. And a voice came from heaven: “You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased.”’ This dove had come to Belgium from Britain; but perhaps, for Raskin, it had come spiritually as well as literally from above. Faith, duty and spying were all intertwined in the priest’s mind.

Material was still coming in as he wrote. The Germans were strengthening their positions on the coast, fearing an English attack. A new division had been installed and there was extensive activity from planes as well as lorries bringing in fuel. Advice was offered as well – if the British were planning to invade then they should avoid delay in moving through the country or the Germans would take all the able-bodied men to Germany. No one had any idea that it would take three long years for the British to arrive.

Finally, he was ready. Raskin took his pen and began the final draft, working through the night of 11 July. He sat at the desk with a magnifying glass to ensure he could cram in as much detail as possible on the tiny sheets of paper. The quill of his pen was precise. Every space would be put to use. A last-minute item of intelligence came in on the morning of 12 July at five minutes to eight. Joye had come through Bruges railway station and had seen a ground air defence post moved. That detail was added in the corner.

Raskin finished with a flourish and a special touch. ‘Our seal!’ he wrote in the bottom corner, adding a symbol which he intended to be a unique identifier of the group and its future messages. It was a circle with a curly L sitting in a V, one side of the V becoming either a cross or a sword, depending on how you interpreted it. Their name was Leopold Vindictive.

There was no more space. The message was ready to fly. The two pieces of rice paper were carefully folded up and placed inside the green cylinder that had come with the pigeon. The cylinder was slotted into the ring around the pigeon’s feet and twisted to secure it.

The group then did something extraordinary, an act contrary to every rule of spycraft. They picked up their family camera and took pictures of the pigeon, and of the message being pushed into the green cylinder. But then, even more extraordinarily, the three brothers and two sisters stood for a family portrait in the inner courtyard. Marie and Margaret are in their aprons, Michel and Gabriel in working shirts with braces. Arseen looks somewhat smarter. At first sight, it could be any other family picture, but look more closely and you can see that Marie, the elder sister, is holding a resistance newspaper, Margaret is holding what looks like a white sheet – the parachute. Arseen holds a pencil, Gabriel the British intelligence questionnaire, and Michel proudly clutches the pigeon. And in front of them, propped against a table with a white tablecloth, is a chalkboard – probably the board that they would normally use to display the latest fruit and vegetable prices for shoppers. But this time, on the board are written the dates of the bird’s arrival and departure, its ring number and the phrase ‘Via Engeland’ to mark its destination. And at the top are three capital V’s – the symbol of Victory, which earlier that year the BBC had called on people to daub on walls as a symbol of defiance.

Taking the photos was a mad, risky and amateurish thing to do, and yet it spoke of something that is impossible to criticize – a deep pride in their work of resistance. Raskin is not in the picture, most likely because he was on the other side of the camera taking it.

There was one final picture to be taken. Michel climbed up onto the roof, where there was an oat-attic. This was the place from which he normally released his pigeons, and so it may have looked less suspicious than it sounds to anyone watching him. Up there he opened his cupped hands and released the bird; a picture captures the precise moment. At 8.15 a.m. the bird rose high into the sky and circled for a few moments to get its bearings. Then it made for the Channel and for England. In seven hours’ time it would have escaped Nazi-occupied Europe and be home in suburban Ipswich.