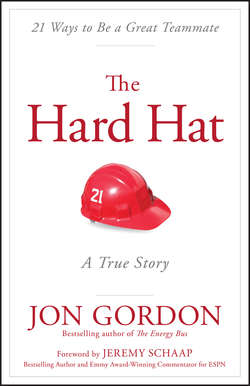

Читать книгу The Hard Hat - Gordon Jon - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FOREWORD

ОглавлениеI remember hearing the news. The captain of Cornell's lacrosse team had died, on the field of play, after getting hit in the chest with a ball. How terrible, how cruel, how utterly tragic. What else could you think? As a Cornell graduate, with a connection to the lacrosse program, perhaps I felt all those things more acutely than most people who came across the news in their newspaper or on the Internet. In a way, the death was more real to me because I had grown up around Cornell lacrosse, I knew Cornell lacrosse players, and I understood how tight knit that community had always been.

Just two years earlier, in my role as a reporter at ESPN, I had written a tribute to the life of another Cornell lacrosse captain who had died too young, but not nearly as young as George Boiardi. Eamon McEneaney, one of the sport's great figures, had died on September 11, 2001, at the World Trade Center, where he worked in finance. When attending his funeral in New Canaan, Connecticut, I witnessed an outpouring of emotion that stays with me even now. Richie Moran, Cornell's longtime head coach, a man I had known all my life, eulogized McEneaney. Totally overcome, he barely made it through his tribute. I have never seen a grown man or woman so unhinged by grief. He was sobbing, and his pain was so pure that everyone in the church could feel it. It was beautiful and awful – an unforgettable coda to a week unlike any other in New York. It was also indicative of the way in which Cornell lacrosse is a family. The current team was there, McEneaney's old teammates were there, and the network of friends and acquaintances he had made through lacrosse were all there.

Then George died on St. Patrick's Day, 2004. That was cruel, too – not because George was of Irish extraction, but because Moran and McEneaney and so many others in the Cornell lacrosse community were. I had never met George. I don't think I had ever heard his name until the day he died, although I assumed we had been together at McEneaney's funeral. But over the next several years, I would come to know George – through his family and friends, at the events they held to honor his memory and to raise money to benefit causes that were meaningful to him.

Every winter since then, a dinner is held in New York – the 21 Dinner, in recognition of his uniform number – and hundreds of George's friends, from home and from Cornell, would attend. There was nothing extraordinary about the gesture. Naturally, people close to George would want to celebrate his life and find a way to remember him. But the dinners – organized primarily by George's Cornell classmate and friend, Jesse Rothstein – would turn out to be anything but ordinary. Even as they embarked on their careers and started their busy post-college lives, George's friends would come together every winter – it seemed always to fall on the coldest night of the year – to remember George. I have been a part of other efforts to memorialize fallen friends; often, attendance and interest are strong in the first few years after the friend has died, then they decline, memories fade, and people move on. That wasn't the case with George. With each passing year, it seemed the determination to keep his spirit alive only strengthened among those he had left behind.

I came to look forward to the event – to seeing George's parents and sisters, his friends and teammates, the honorees from the world of education, to which George had pledged himself as a Teach for America volunteer. At one of the dinners, representatives of the Native American reservation on which George was going to teach were in attendance. They came to pay their respects to the young man who had grown up in a world of privilege but had decided to live among them in very different circumstances for at least a couple of years.

It seems too easy to say, but my faith in humanity was always restored by the 21 Dinner. It was also made meaningful to me by the organizers, who honored my father at the event. Like George, he had worn number 21 playing lacrosse for Cornell. He had died on December 21, 2001, in New York, after hip surgery at the age of 67 – too young, but old enough to have lived a full, rewarding life, which George had been denied.

Seeing George so fondly and well remembered at the dinners – I was a mostly superfluous master of ceremonies each year – I felt as if I came to understand why he meant so much to so many. The way people talked about him, I think I could draw a fairly accurate portrait of a young man with so much to offer. There was the selflessness, the work ethic, the kindness, the gentlemanliness, and a total lack of arrogance or sense of entitlement. He seemed to be exactly the kind of person we could all respect – someone Eamon McEneaney, my father and I, and anyone else would have considered themselves privileged to have known. Of course, not having met George, there is still much I didn't know about him. This book remedies that. Clearly, he was someone worth knowing.

– Jeremy Schaap